Читать книгу Walk Like a Mountain - Innen Ray Parchelo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

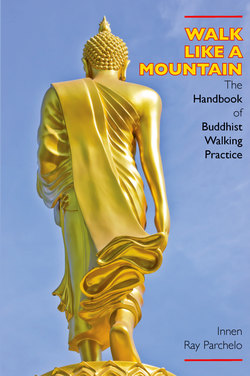

ОглавлениеPREFACE

DWELLING

When the spring stirs my blood

With the instinct to travel,

I can get enough gravel

On the Old Marlborough Road.

What is it, what is it

But a direction out there,

And the bare possibility

Of going somewhere?

If with fancy unfurled

You may leave your abode,

You may go round the world

By the Old Marlborough Road

From The Old Marlborough Road,

Henry Thoreau, Walking

WHY LEAVE YOUR ABODE?

Its hard for me to separate walking from other practice forms, since it became fused to my practice regimen very early on. Walking had been a time of reflection for me from my early teens, well before my introduction to Buddhadharma. There seemed to be something in the steady rhythm of a walking pace that supported those times I reserved for contemplating the big questions of life for the first time.

Like the 19th century American philosopher-walker, Henry David Thoreau, I felt it important to combine reflection and walking. In his essay called Walking, he notes: “…moreover, you must walk like a camel, which is said to be the only beast which ruminates when walking” (Walking, p. 7). And like Thoreau, as much as a city teenager could, I sought relief from the roads and highways. I very often waited until dusk or after dark, when I could visit the many quiet ponds, parks and canal-trails near my home. Again, like Thoreau, I understood the difference between the urban thoroughfares fronted by shops, and those other, more desirable spaces where the commercial grid dissolved into foot-paths and river-banks. He proposed:

“When we walk, we naturally go to the fields and woods; what would become of us, if we walked only in a garden or mall.… Roads are made for horses and men of business. I do not travel in them much, comparatively, because I am not in a hurry to get to any tavern or grocery or livery-stable or depot to which they lead. I am a good horse to travel, but not from choice a roadster.” (Walking, p. 8, 12)

An early contemplative walking experience occurred while I was falling into what was to become my life-long thrall with Buddhadharma. In my first-year studies, where I began to explore Indian meditative history and practice, I was living in the part of Ottawa which nestled along the famous Rideau Canal. Adjacent to the Canal, which winds for about eight kilometres from the Ottawa River, to my then-school Carleton University, was a small pond. Late one Saturday evening, restless from too much essay-writing, I left my apartment to walk the quiet streets, towards the canal. After some 30-40 minutes, I found my self on the upper bank of a small pond, and there, with the nearly full moon, the warm early fall air and echoes of the Bhagavad Gita and Shakyamuni’s quest, I too sat down. I probably imagined some trans-temporal link between my teen-age reflections and those more epic contemplations. Like those masters to whose lives I aspired, I began to find the harmony between sitting and walking practice.

In my early twenties, following my formal undergraduate university training, I began exploring organized Dharma practice in earnest. As it was for many contemporary Westerners, it was Zen I took to be real Buddhism. And, like so many, I took sitting practice, zazen, preferably staring at blank walls, to be the only valid practice. Throwing myself into formal Dharma practice, first through Rinzai Zen style and later Soto Zen style, I learned the most common walking practice, kinhin. The two schools have their own distinct versions of walking, one fast, the other slow, each an expression of the broader distinctions of the two schools. I didn’t know or appreciate those differences and adopted the Soto style, a slower, measured pace, one which seemed familiar, so much like my pre-Buddhist walks. As I was taught as a good zen practitioner, I made walking an auxiliary practice, always subordinate to zazen. It was fine, I believed, if I wanted to go for walks, but that bore no relationship to the time on the mat. Living by then in a dirt-road rural location, I was offered countless opportunities for unstructured and undirected wandering. However, I always felt a certain tension between kicking stones down the road, exploring fields without much purpose, not unlike Thoreau a century earlier, and the Spartan discipline of wall and zafu. Walking, I knew, should be second best, or at least a minor distraction.

In an odd way I may have been called to walking. My father was a chemical engineer who left his lab at the Steel Company of Canada in Hamilton, Ontario, to join the group of scientists and researchers brought together to grow the agency that is now Statistics Canada. His lab-partner and close friend, a certain Ray Lowes, remained behind for a successful career at that Hamilton plant. My father brought his friend and I together with his name, although he was most commonly just known as ‘Lowes’. Lowes and his wife, Jane, visited us from time to time in Ottawa. This often took us ‘up the Valley,’ as we say in Renfrew, for a hiking and camping trip to Algonquin Park. For us, Lowes meant the woods and walking.

Back in Southern Ontario, Lowes continued walking in the woods. He fell in love with a certain collection of walks which ran past his home on the Southern Niagara Escarpment, winding northward past Hamilton, Milton and Caledon. In 1960 he outlined his vision for an expanded and connected set of trails which would extend from just outside Buffalo, New York, up to Tobermory, at the edge of Lake Huron, some 800 km to the north. Shortly thereafter, along with three other founders, Lowes began to organize the trail. The nine Regional Clubs which oversee the trail were established. In 1967, Canada’s Centennial Year, a cairn at Tobermory, the northern terminus of the Bruce Trail was unveiled. Seven years of determination, support, vision and hard work were realized when the Bruce Trail was officially opened. The Bruce Trail (http://brucetrail.org/) is now the oldest and longest continuous footpath in Canada. The Bruce Trail Conservancy has grown steadily since then, purchasing vulnerable natural treasures and ensuring their sustainability for future generations of walkers.

Over the next decades and phases of my life and practice affiliations, I continued to walk for practice, pleasure and adventure. In the country, walking was an accepted and expected mode of transport. Going to the grocery store in the village was a walking chore. Visiting friends often involved walking to and about their properties or walking to a swimming spot. More and more, I explored walking practice itself, practicing with walks into the woods where I would sometimes do my zazen. Although I didn’t know it, I was investigating the step and breath counting, the silent recitation and mindfulness of the natural world that I would learn later as traditional walking practices.

As my world became larger, I learned that not everyone valued walking as I did. In fact, on one occasion, I came to understand that it was viewed as peculiar and even suspicious. One Christmas, I traveled by van with a couple of buddies down the East Coast of the US, headed for respective families in Virginia and Florida. At the end of one long day on the road, we stopped for an overnight with friends in Maryland. Their home was in one of those sprawling 1980’s suburban developments, which had been laid out in a former farmer’s field, now paved over and re-constructed with winding utilitarian sidewalk-free roadways which only served to connect neighbourhoods. Commerce was neatly tucked away in a carefully concealed mall. All original natural details had been erased in preference for someone’s idea of a natural landscape – one which omitted trees.

On our dusk arrival and after ten or so hours on the road, my friend, John, and I decided it would be a pleasant distraction to take a walk. We set off from the house and, with no particular goal in mind, made our way around the development. Within about twenty minutes a police cruiser pulled up beside us and asked us our business. We explained we were out for a walk. The officer seemed completely non-plussed by the idea of people moving around the neighbourhood without the aid of a motorized vehicle. He left us alone, but not without a warning that this whole walking thing might be risky to us or unwelcome to the neighbours.

My next introduction to Buddhist walking was in Sri Lanka, a few years later, where I was participating in an international exchange program, Canadian Crossroads International. I was placed within the huge extended family known as Sarvodaya Shramadana (The Awakening of All through the Gift of Shared Labour). This “village reawakening” movement had hundreds of sites all over the island, each deeply embedded in village life. The Sarvodaya movement, the brainchild of Buddhist and neo-Ghandian school teacher Ari Ariyaratne, sought (and still seeks) to transform villages all over Sri Lanka through an interfaith philosophy summarized by the slogan “we build the road, the road builds us.” Their trademark activity was organizing road-building work-bees. Hundreds of villagers would come together, to share their labour and participate in the creation of entirely new roads. Men, women and children, of all ages, each took some role in hauling stone, clearing jungle, or feeding the crews.

My home-site, in a kind of regional outpost, near the central jungle-fringed city of Kegalla, brought me into an close collective living arrangement with thirty or so local village youth, all of whom, like most Sri Lankans, were Theravadin Buddhists. We frequently moved around between villages and projects by either an old Land Rover, diesel-seasoned local buses, or, of course, lots of walking. Anytime we needed to go down the valley to the larger village of Randeniya, it was an hour-long walk to the nearest “bus halt.” Wherever one might want to go, be it the bustling city life of Colombo, the tourist beaches along the south coast or the mountain tea-estates, one should expect a substantial pedestrian stage to the journey.

One morning at the centre, while I was doing zazen in my room (a re-purposed cement storage building), I became aware of one of the teenage trainees peeking in my paneless window. It seemed odd to me that sitting should interest another Buddhist. What could be more natural than doing sitting practice at wake-up? Later, my friend explained that in Sri Lankan Buddhism only a rare and senior monk might do extended meditation. Most people would do a brief three minute contemplation, but nothing as formal as zazen. The young men spying on me were wondering what sort of person I was to be doing this.

Later, my friend, Tilak, asked me if I might like to spend some time in another Sarvodaya location which was a Buddhist monastery in the hills. The clergy, I came to understand, were very much integrated into the Sarvodaya activities. I leapt at the chance, and within a week was transported to a monastery a few hours away and settled into my small, simple quarters, like a lay dorm. I was the only layperson and had only a little to do with the monks, since no one spoke English, and I think it was not proper for a layperson, even the esteemed “suddhu-aya” (older white brother), to mix with monks.

It was here that I witnessed another walking practice up close, although not very personally. Each day the monks would line up, bowls in hand, and file down the mountain road to another village for their daily alms round (which we will explore later as Walking Practice # 3). I was never invited but did come to understand the centrality of that walking practice for them. This was more or less the only way they secured food for themselves, so walking was woven into both the contemplative and daily living routines of their lives. That same thing happened, and has happened for centuries, in monasteries all over Sri Lanka and most other Buddhist nations. It would be years before I came to know the meaning of the alms-round for bringing Dharma to the villagers.

My months in Sri Lanka also introduced me to another type of walking which is also a very common religious practice, one which appears in most world religions: pilgrimage (which we will later meet as Walking Practice # 6). This practice sets the practitioner on a walking journey which physically, emotionally and symbolically repeats the steps of some ancient figure or visits the site of some milestone religious event or artifact. In my case, it was several visits to the treasures of the golden age of Sri Lankan Buddhism. In Anuradhapurra and Polonnaruwa, I walked through the one-square-kilometre city ruins of what was one of the largest cities of the 4th century BCE. The city became part of the new Buddhist expansion only two centuries after the Buddha’s own life. Its boulevards, religious buildings and monastic residences are home to many extraordinary architectural treasures. Later in my trip, in the South of Sri Lanka, I walked through the gardens, stepped through the giant lion’s claw threshold and climbed the stone staircase to the top of Sigiriya, the Lion’s Rock,. This gigantic volcanic rock rises over 1,200 feet above a flat plain and has been a royal retreat with a surprising gallery of Buddhist paintings and, more usually, a Buddhist monastery. It too dates from the earliest days of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Unlike the desert plains of Anuradhapura, the breathtaking vista from atop the Lion’s Rock provides the kind of sobering perspective on the world which gives one pause. At that time, I was not sufficiently knowledgeable about pilgrimage to benefit from all the practice has to offer. Nonetheless, it still took the form of a pilgrimage, in the sense of leaving me with life-shaping memories and inspiration and, more than thirty years later, continues to connect me with my chosen faith.

These experiences signified two parallel abode-leaving transitions – my leaving my family home and entering young adulthood, and my leaving the vagueness of my late teen spiritual musings for the more formal Buddha-way. Both were equally important in forming my spiritual identity. From my naivete and lack of worldliness, I had almost no sense of how important this abode-leaving would be. Further, it seemed coincidental that walking should be so much a part of these leavings. As with many pilgrimage experiences, it is only through reflection over the years following that understanding and meaning emerge. Leaving one’s abode is itself an act of faith, part of that mix of conviction, despair and hope which drives our search for new meaning.

UNFOLDING THE MAP

Like any good walk, this book covers a variety of both new and familiar terrain. It offers gentle strolls, steep climbs, shady nooks and expansive vistas. It won’t wear you out nor will it (I sincerely hope) fail to challenge you. Like any good book or walk, this one is a journey. It starts where we are and points to a destination without revealing all of its adventures too soon. It’s a book to be read and a book to accompany you on whatever walks you take.

Any walking reader will already have a similar slim bookshelf with titles about walking. It may feature one of the many pilgrimage diaries, like Dempster’s Neon Pilgrim, or Tony Kevin’s Walking the Camino. There will be a selection of technical books, perhaps some edition of Colin Fletcher’s The Complete Walker or titles that begin: Hiking the…, or Nordic Walking for…, or The.…Walker. The reflective walkers will have Basho’s Narrow Road to the North, Thoreau’s Walden or My Life in the Woods, and probably his Walking. The spiritually-oriented will have Halzer’s Warrior Walking or Kortge’s The Spirited Walker. For the religious, there may be a copy of Bunyan’s Pilgrims Progress, Steven’s thorough The Marathon Monks of Mount Hiei or Thich Nhat Hahn’s multi-media collection, Walking Meditation. Every one a great companion.

This book is a unique resident for your bookshelf or backpack. This is the first book to deal with the many forms of Buddhist and other contemplative walking practices in a comprehensive way. It is the first to address the interests and needs of Buddhists and other spiritually-minded walkers in actually using traditional and more recent Buddhist and Buddhist-friendly foot practices as part of their contemplative journey. Its written with these people in mind. You’re likely one of them if:

• you already have some regular Buddhist practice and may have had some introduction to kinhin walking;

• you have some form of meditation practice, Buddhist or otherwise, and need something to provide some variety between or as an alternative to sitting;

• you are curious about reflective practices, especially Buddhist, but find the prospect of sitting quietly for very long to be a bit daunting;

• you have participated in a pilgrimage or other contemplative walk and want to expand on that experience;

• you regularly enjoy walking and feel the need to give it a more structured reflective dimension;

• you have participated in socially-conscientious or fund-raising walks.

People are drawn to walking for many more reasons. Rather than the reasons above, yours might include walking for fitness and/or weight loss, competitive and race walking, trophy or ‘bucket list’ walking (that is, to collect trails as achievements), and walking for human or animal companionship. There are merits and benefits to each on this second list, however, in this book, we are concerned with the first list and have little to contribute to that second collection of interests.

SCANNING THE TERRAIN

Through all of this, I discovered there are many books about walking. Some call it walking, some call it hiking, the more common North American term, others trekking, which one sees more often in Europe. There are those that locate trails of interest and detail highlights one might pass en route. There are instructional guides which explain types of packs, boots, poles and so on. There are memoirs of “great trails I have done.” There are manuals that extol the health benefits of walking as exercise. There are training guides that prepare one for competitive walking. There are books on walking Tai Chi, walking yoga, warrior walking, Nordic walking and walking chi kung. City, country, forest, mountain, pilgrimage, tourist, on and on.

As mentioned above, this is the first book to address the interests and needs of Buddhists and other spiritually-minded walkers in actually using traditional and more recent Buddhist and Buddhist-friendly foot practices as part of their contemplative journey. Our concern here is understanding and using those traditional and newer Buddhist foot practices within a personal contemplative training regimen.

There has been some debate about a proper term to describe the kind of walking I mean here. Some readers have objected to psycho-spiritual, some to the term spiritual, some are uncomfortable with the term religious. My intention has been to appeal to both the professional and lay psychotherapy reader, especially those using mindfulness methods, and to readers with more of a concern for religious issues, largely but not exclusively Buddhist. The term which has gained greatest resonance with me has come to be contemplation. This seems to encompass multiple styles of meditative practice, therapeutic mindfulness, and a wide inter-faith perspective. For that reason I will stick with contemplation/contemplative when referring to these kinds of walking practices.

In many Buddhist practice environments, walking is often either ignored as a practice mode or treated as an optional practice, more as a relief from sustained sitting practice. Here, we assume a great value for walking and concentrate on the how-to aspect of walking practice. In fact, we will come to understand walking practices as a fully legitimate and comprehensive set of practices. We will come to appreciate their value as a complement to more familiar sitting methods to fulfill the Buddha-way. As Zen Patriarch Yin Kuang explains:

Since sentient beings are of different spiritual capacities and inclinations, many levels of teaching and numerous, methods were devised in order to reach everyone. Traditionally, the sutras speak of 84,000 (i.e. an infinite number depending on the circumstances, the times and the target audience.) All these methods are expedients - different medicines for different individuals with different illnesses at different times - but all are intrinsically perfect and complete. Within each method, the success or failure of an individual’s cultivation depends on the depth of practice and understanding, that is, on his mind.

Pure-Land Zen, ed. Forrest Smith, p. 7

PHASES OF OUR JOURNEY

Parables, stories and metaphors of travel and journey are part of the fabric of our culture. As I write this, the radio music in the background is singing the praises of “the broken road which leads me back to you,” just one example of such stories of life as life on the road. In chapter seven of the Lotus Sutra, which is sometimes called The Apparitional City, we are told of a leader who responds to the distress of those around him by leading them on a journey, promising them the greatest treasure at the conclusion. It is in this chapter that we are introduced to the teaching of skillful means (upaya) whereby a great teacher constructs their teaching according to what is most resonant for those in need. In this case, the leader chooses a journey as his skillful means.

This book is about journeys, and takes the form of a journey. Every journey, no matter the length, purpose or mode of travel is a transition, a rite of passage, a transition ritual. In its simplest form it has three phases: separation or home-leaving; limin or pivot-point; and re-connection/re-collection. Separation or departure is recognizable as our leaving the family-hearth, making a break, however large with patterns and past. Often it is a home-leaving. Most importantly, this separation is purposeful. We are not driven onto the road, we deliberately step onto it with reasons and aspirations unique to ourselves. At some point we reach the limin, we become liminal. This liminality has an ambiguity, as Turner explains: “liminality is not only transition but also potentiality, not only ‘going to be’, but also ‘what may be’.” (Image, Turner, p. 3). Anyone who has walked a labyrinth understands that something shifts at the centre, what was approaching is now leaving, seeking has been satisfied. The ancient Romans used to place the two-headed god, Janus, in their doorways for this same reason. Being on the threshold or limin, Janus looked ahead, down the road, and back into the familiar, literally, the family hearth. The final phase is the re-entry, re-crossing the threshold back into the home we left. It is a re-connection, and yet, because of what we have become on the journey, we recollect how we are different.

Within the journey on which we are embarking are three parallel journeys. The first is the unfolding journey of walking in Buddhist history and practice. We’ll join Shakyamuni, Bodhidharma, Jizo-bosatsu and countless others who unfolded the Dharma step by step. The second journey is our own journey of practicing walking. We explore how we can introduce foot-body-mind practices into the collection of practices which guide our own spiritual lives. We each will have a unique path to walk and that too will fork and meander as our practice-lives evolve. Finally, there is my own journey with walking, a pilgrimage that approaches fifty years. I hope to share how I’ve made my way along this wonderful Dharma-path, how I learned what Thich Nhat Hahn tells us – “peace is every step.”

Walk Like A Mountain is divided into three parts:

Part I: Preparations

• Every journey demands preparation – destinations to name, maps to collect, baggage to secure. In this part, Chapters One to Four, we consider the Buddha-way as a foot path, we imagine where we might go and we anticipate the journey from the perspective of the threshold.

Part II: Journey

• Building on the metaphor of crossing and dwelling, we examine practices that are journey-like in form. In Chapters Five to Eight we introduce the first seven of our set of walking practices, each of which appears in the form of a journey.

Part III: In-between Spaces

• Introducing a second metaphor for walking practice, that of inhabiting in-between spaces, we meet a set of practices which take that form. In Chapters Nine and Ten we consider an additional four practices, with emphasis on newer practices which lead us beyond traditional Buddhist practices.

The main chapters of our journey-book will use a journey form which is marked by the chapter title. In each chapter we reflect on the meaning of that phase of the journey. We identify a set of ten-plus foot practices, which combine Buddhist and modern affiliated practices. We’ll examine the origins and place of walking in Buddhist history, the forms of these distinct practices, describing the form and weighing the value of each. We’ll present simple step-by-step (so to speak) directions to make these strong elements of your practice.

We’ll start off, as any Dharma practice instruction usually does, with a consideration of physical postures, body, foot and hand, and the importance of breath. We make some notes on accompanying equipment, not from the perspective of a ‘buyers’ guide’, but more to enrich the practice dimension of these practices. Finally, since not all Dharma practitioners are able-bodied, we look into how those with physical disabilities can modify foot practices for their use.

You are encouraged to consider ways to direct your own practice to include foot practices. You can follow along the map of our journey. Alternately, if you have some appreciation for the general form of the practices (chapter 2), you can explore each of the ten forms (chapters 5-9) in whatever order you prefer. Chapters 5 through 9 divide the types of walking practice (which actually incorporate more than ten discreet forms). We begin in Chapter 5 with indoor forms, what most people are familiar with, introducing along the way the style of ‘Tai Chi walking’ which fewer people know. In Chapter 6 we meet takuhatsu or alms-round walks and some considerations of movement as a part of general monastic life. In Chapter 7, we try out some combined practices, where we walk and perform other practices, such as circumambulation, nembutsu or bowing. In Chapter 8, we look at the major long walking practices, including both the world-wide phenomenon of pilgrimage and the imposing kaihogyo practice developed by Japanese Tendai. In Chapter 9, we consider practices where walking takes on a symbolic form. In particular, we explore how the Pure Land schools envision their practice as a journey and how mandala practices are based on a journey metaphor. We close Chapter 9 by looking at two more recent methods, a primarily European model, labyrinth walking, especially the newer approaches to this practice, and, second, what Thoreau referred to in his writing as ‘sauntering’. The final new method emerges from 20th century social activism and Engaged Buddhist activities, that is, using walks for social change.

If you have been sitting before, you will find that your motionless experience can help to unfold the possibilities of foot practices. If walking is more of your first entrée into Buddhist practice, recognize that it is not a complete alternative to sitting forms. No matter how much walking you do, some experience with sitting practices is necessary to ground yourself in Buddhist practice. Later in your practice, as part of the teacher-student training decision process, you may choose, as I have, to focus in part or entirely on a foot practice. For the novice, it would be foolhardy to avoid the ‘refining fire’ of thorough and disciplined sitting methods.

I further encourage you to approach each practice on its own merits, whether you have some experience or none. Practice each form as a new practice, one which invites you into a new way of meeting your body and mind experiences. As with any practice, it is foolish to judge the practice on a superficial exposure. You will need several months, even years, of regular practice to cultivate the forms and learn what it has to offer.

However you approach or practice, embrace the journey. Dharma practitioners have made it their proving ground for centuries. As they say on the Shikoku, that Japanese pilgrimage which encircles Shikoku Island for 1930 km, dogyo ninin, “a practice of two together,” that none of us ever walks alone. We always have the company of centuries of walking Buddhists, of countless Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, all of whom urge us forward, urge us to use the road to penetrate the Way.