Читать книгу Walk Like a Mountain - Innen Ray Parchelo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

STIRRINGS FOR THE ROAD

The green mountains lack none of their proper virtues; hence, they are constantly at rest and constantly walking. We must devote ourselves to a detailed study of this virtue of walking. Since the walking of the mountains should be like that of people, one ought not doubt that the mountains walk simply because they may not appear to stride like humans.

To doubt the walking of the mountains means that one does not yet know one’s own walking. It is not that one does not walk but that one does not yet know, has not made clear, this walking. Those who would know their own walking must also know the walking of the green mountains.

Mountains and Waters Sutra, Dogen, transl. Bielefeldt, Stanford University

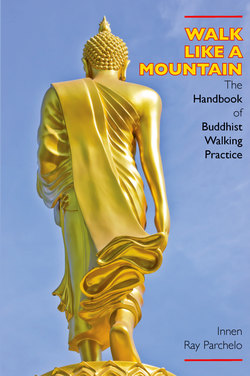

WALKING – THE HIDDEN LIFE OF THE BUDDHA

In the north of Sri Lanka, in the desert regions of Polonnaruwa, at a place named Gal Vihara, there is a magnificent and isolated trio of larger-than-life statues carved out of local stone. Representing “the vogue…of carving colossal images of the Buddha on the vertical faces of rocks” (The Art of the Ancient Sinhalese, Nirvatana, p. 22) which occurred in the 12th century ce, figures are scattered about a barren landscape. The scale (one stands 42 feet tall) transforms the viewer into Lilliputian dimensions, barely up to the Buddha’s kneecap. Not unlike examples of Buddha statuary which began in India a few centuries after the Parinirvana, and appear all over Asia, and now in the West, the Gal Vihara Shakyamunis are represented in each of three classic postures.

One is the reclining pose, with the Buddha on one side, with his head resting on his hand, both propped up on a tubular cushion support. This is the least common pose and it is unusual to view the trio together this way. The other two, which are close by, along with several more from other centuries, are posed in the most familiar postures – standing and seated. The standing can be with arms to the side, the over-length Buddha-identifying arms and hands flat to the thighs or with hands held in one of the familiar mudras, or, as seen elsewhere at Polonnaruwa, with arms crossed over the chest.

By far, the most common Buddha pose, found in all sizes, all materials, located close to massive temple figures or, much smaller, tucked away in gardens, is the seated Shakyamuni. This is also true in secular art where seated Buddhas can be found as incense holders, wiener mascots (as with the Picton, Ontario product called Buddha Dog, see http://buddhafoodha.com) and the ubiquitous theme of countless cartoons of an ascetic under a tree or on a mountain top. An assortment of classic hand positions or mudras may be used, but the pose always shows Shakyamuni, sitting. Sitting in padmasana, sitting cross-legged, sitting straight-spined and sitting staring ahead.

Of course there are mythologic depictions of flying Buddhas, even flying seated Buddhas, or occasionally, Buddhas standing amidst a crowd of followers, engaged in one of his celebrated sermons. The least common pose, and the one whose absence presents as a large question mark for us here, is the walking pose. Over the centuries, less than a handful of depictions have chosen such a pose. An 11th century Japanese artist created the unusual standing Buddha, Amida Looking Back, from Zenrin-ji temple in Kyoto. It poses the standing Buddha, right hand in the wheel-turning mudra, and head glancing over the left shoulder, compassionately checking for suffering beings who may have been left behind. According to another story, this image startled a dozing priest, Eikan, who fell asleep while doing walking nembutsu practice. There is another beautifully slender Thai statue which presents Shakyamuni in full stride.

If a walking Buddha is rare, then the rarity is clearly compensated for by the image of Jizo Bosatsu, the walking Bodhisattva, which can be seen almost everywhere in East Asia. Even when he is not actually shown stepping along, he carries the shakujo, the pilgrim staff. This reminds us of his vow to walk through The Six Realms of Existence, bringing Dharma to beings, especially those unable to hear it due to the situation of their unhappy birth. Further, his figure is commonly located along roadsides, at crossroads or anywhere fellow walkers, travellers and pilgrims may need his assistance.

Even given the activity of Jizo, (whom we will meet more fully in Chapter 2), walking practices remain minor and usually adjunctive for most practitioners. Herein lies the puzzle which occasioned this book: why are walking practices relegated to the back rows of Dharma practices? Consider the pre- and post-Enlightenment activities of Shakyamuni once he dismounted his beloved Kantaka and bade farewell to his loyal manservant, Channa:

…and so he passed

free from the palace.

When the morning star

Stood half a spear’s length from the eastern rim,

And o’er the earth the breath of morning sighed,

Rippling Anoma’s wave, the border stream,

Then drew the rein, and leaped to earth and kissed

White Kantaka betwixt the ears and spake

Full sweet Channa: “This which thou hast done,

Shall bring thee good, and bring all creatures good.”

The Light of Asia, Arnold, 4th Book

There is no biography of Shakyamuni which disagrees on the facts. We have a description of his departure, his studies with the four renunciants, his near death and decision to seek awareness beneath the Vesak moon. We know of the temptation and victory. His choice to return to the world of dukkha, his various sermons. We know of his stops and addresses which spanned some forty or so years before his Parinirvana. Forty years or so of travels.

Imagine, if you will, an itinerary for the Buddha at almost any time of those forty years, with the exception of the ‘rains’ when they took shelter for that period of weeks. There would be time for seeking food and eating twice daily, time for sleep and, one assumes, the usual bodily necessities. There would be time for pauses on the way, perhaps to visit some royalty or other dignitary. There were periods of formal sitting meditation practice, in whatever grove or shade could be found. However, during most of the time spent over those forty-odd years they were engaged in walking. Lots of walking. Any scan of the maps of the Buddha’s travels will confirm that there were major distances between sermons and stops, and so the majority of His and those of his followers’ waking hours were spent wandering on foot hither and yon over the dusty roads of North India.

Again, as Arnold imagines:

I choose

To tread its [the Earth’s] paths with patient, stainless feet,

Making its dust my bed, its loneliest wastes

My dwelling, and its meanest things my mates;

Clad in no prouder garb than the outcastes wear,

Fed with no meats save what the charitable

Give of their will, sheltered with no more pomp

Than the dim cave lends or the jungle-bush.

The Light of Asia, Arnold, 4th Book

In some respects, the life of the Buddha is a model for the leader in chapter seven of The Lotus Sutra, mentioned above, who takes his followers on a perilous journey leading to the ultimate treasure. If we accept that Shakyamuni Buddha was the presentation of the Living Dharma, and that his every gesture was the expression of the Way, we must imagine the great amounts of teaching which occurred while the first Sangha walked and walked, year after year. Its inconceivable that during all that time there wasn’t some structured practices of reflection, chanting or even question-and-answer that emerged. Could all that have been so trivial that it doesn’t merit a place in the practice routine of the Buddha and his followers?

The question is worth noting, as we look into the performance of these practices. However, the deeper examination and possible answer to such questions belong to another, as-yet-undertaken study. For now, we raise the puzzle while we ourselves join the Buddha, feeling the Earth beneath us and “…tread its paths with patient…feet.”

WALKING PRACTICE AS METAPHOR

Our journey here may not reveal to you the secrets of green mountains walking or an ultimate treasure, but we will most certainly follow Dogen’s sage advice, and investigate clearly our own walking. Although walking might seem a minor practice, compared to the highly-praised seated postures, walking inspired the early Buddhist imagination in other ways. Way, path, vehicle, step. These are the prominent metaphors of Buddhadharma. Consider:

• The fourth of the initial and pivotal Buddhist teaching is, of course, the Eightfold Path, the arya-arta ga-marga. A marga is a well worn path, such as a wild animal would leave behind, and also suggests an expedient route, a passage or the proper course;

• Using another road metaphor, all the schools of Buddhism refer to themselves as yanas, vehicles. Hence, we have the Lesser Vehicle (hina-yana), the Great or All-Encompassing Vehicle (maha-yana), the Vehicle of the Thunderbolt (vajra-yana) and The Harmonizing Vehicle (eka-yana). The sense here is of practice as a conveyance, that is how one gets from here to one’s destination; thus, these vehicles have the capacity to carry us to liberation or over the river of suffering;

• One of the most beloved books in the early Buddhist canon is the Dhamma-pada, literally, Dharma steps or footsteps;

• In the earliest Buddhist art, images of the Buddha were forbidden and symbols for the Teacher were used. One popular symbol was the padanka, the Buddha’s footprint, which became an object of worship;

The padanka symbol

• The story of the infant Shakyamuni, following his miraculous birth, includes the detail that, unlike the awkward stumblings of most infants, he stood up and took three bold strides, symbolizing his conquest of the Three Worlds. As he stepped, brilliant lotus flowers sprang from the earth. Its worth noting here again that with all the possibilities of things he could have done to show his extra-ordinariness, it was walking which characterized this miraculous child.

Curiously, with all these road metaphors, the word for teaching remains Dharma, which is a symbol of something static, not moving. It suggests a pillar or foundation – a set of rules or a natural order. Perhaps the common contemporary (to the Buddha) usages of Dharma in Hinduism simply transferred over to Buddhist teaching. As Buddhism moved across into China and Japan, it became more associated with Tao, The Way, the foundational concept of Chinese religion which captures more of the sense of movement and flow.

WALKING AS A ‘YOGA’

Walking practices, as we will see, are usually noted as adjunctive practices, such as a relief from sitting meditation, as with doing kinhin, as special practices, like the kaihogyo, which only the exceptional even dare to perform, or as instrumental, such as walking while doing nembutsu recitation. This book will take walking practices, not merely in these various ways, but as an integrated set of practices.

THIS HANDBOOK’S INTENTION: WALKING AS CONTEMPLATIVE PRACTICE

In a remarkable book, Crossing and Dwelling: A Theory of Religions, the socio-anthropologist, Thomas Tweed, proposes a metaphor to describe what religions are. He sets out:

Religions are confluences of organic-cultural flows that intensify joy and confront suffering by drawing on human and suprahuman forces to make homes and cross boundaries. [These two] orienting metaphors are most useful for analyzing what religion is and what it does: spatial metaphors (dwelling and crossing) signal that religion is about finding a place and moving across a space, and aquatic metaphors (confluences and flows) signal that religions are not reified substances but complex processes.

Crossing and Dwelling, Tweed, pp. 54/59

This intriguing and deeply satisfying conceptualization resonates strongly with a book about the place of walking in one of the world’s great religious traditions, Buddhism. Space does not permit us to pursue Tweed’s metaphors further, but he is successful in providing us with a suitable metaphor for this book itself.

We will adopt, in fact we already have adopted, this dwelling-and-crossing metaphor in two underlying ways: firstly, in conjunction with the ‘three phases’ metaphor introduced in our Preface, and the ‘chapter-map’ of our journey through Buddhist walking practices, the metaphor of crossing/dwelling enriches the journey metaphor, transforming it; and secondly, as a template for understanding the structure of any walking practice. We will see the dwelling/crossing frame can guide us in how to use the practices.

Let’s look in a little more detailed way at how our journey will move us from dwelling to crossing and back again.

Part 1: Preparations

Preface: Dwelling

We began in the known, the many rooms of and windows on our world, familiar and secure. In our meeting, The Preface, someone (myself) unexpectedly reports back with news from their travels. A question mark suddenly appears beside our calm world. A new way of being in that familiar world is proposed. The possibility of a new journey is raised, with something of how and why we might take it and what we might explore and learn. As in our usual world, this ‘travel bug’ must be scratched.

Chapter 1: Stirrings

We are now in the world of Shakyamuni Buddha, walking across North India, day after day, year after year. We step back from the sermons and the drama. We, who are his modern day entourage, observe his everyday life, treading dirt roads, resting in groves, finding a next meal. We step back and wonder what might this have to do with the Great Awakening. Could this to-ing and fro-ing really have nothing to do with being fully awake? Are the travels of Shakyamuni just filler, something to do around the real practices? In what ways has our 2500 year tradition formulated walking practices which we can employ on the Dharma Path? We will leave our comfortable dwelling and take to that road to join our Sangha-companions in their walk.

Chapter 2: Imaginings

A strange and compelling vision takes shape in our hearts and now our bodies. We begin to feel, in our bodies, the movement onto the highway. We recognize we are arranging our bodies for travel, and we need to remember the efficiencies of posture, step and breath. Although we may be walking alone, we remind ourselves that each step is dogyo ninin, two walking together. Who, we wonder, will be our silent companions? In whose steps are we following?

Chapter 3: Threshold – Foot and Step

With a deepened sense of how we ought arrange our bodies, before we set off, we check our most important equipment for the journey – our own body. Napoleon’s army may have marched ‘on their bellies’, we will have to rely on ankle, foot, toes. Our strength will be our posture and breath. We will need to understand these intimately and we will use the lenses of both modern Western medicine and traditional Chinese medicine to inform our understanding. We will consider this journey as an exercise in bio-mechanics, and of ki-energy flow – one which takes place at the margin between earth and sky.

Chapter 4: Threshold – Preparations

Our determination set, having let go of habits and routines, we must gather around us the necessities of the road. We check equipment, pack knapsacks, refit boots with stout new laces. We consider our mentors –centuries of pilgrims, monks circling stupas, super-athletes coursing up and down a sacred mountain. They will recommend what we might need on our journey –can we really get by with only a begging bowl and a staff? We are struck by Jizo, the Eternal Pilgrim, trudging through the Six Realms of Conditioned Existence, his simplicity – the pilgrim’s robes and his shakujo, the sturdy staff which supports his pace and whose jangling rings announce to all beings that the Dharma-messenger is approaching.

Some of us wonder whether we are fit for this journey. We wonder about old bones, injuries or even more permanent disabilities. Will these force us to stay behind. What can our predecessors advise?

Part II: Journeys

Chapter 5: Journey - First Steps

Our destination clear, all preparations made and a trusted map in hand, we take the first steps away from our daily lives and towards an adventure, a learning and, with luck, a transformation. As those who join the road do, we ponder the practice habits we know. Most of us turn to the archetype, the cross-legged monk, the seated Bodhisattvas and the Buddha, in repose on a lotus throne. Some may have tried the walks that divide rounds of sitting practice, some may understand how walking is the continuation of the practices of sitting. We frame our questions, we engage our curiosity, we have formed our intention for the road. Now on the road, we begin with our reliable and familiar practices.

Walking Practice 1: Kinhin and Tai Chi

Most styles of Buddhist practice include some form of formalized walking practice. The most common is kinhin, ‘just walking’. It is characterized as the practice form used to vary periods of sustained sitting practice. It has its own posture and can be done in a variety of paces, from glacially slow to a near sprint. Since it is usually twinned with sitting, it is done indoors, contained within the actual sitting space. Others, most famously Thich Nhat Hahn, have promoted a moderately paced walk out of doors. His form breaks the traditional pattern of a line of practitioners. Video of him leading a walking practice resembles a swarm or wave moving across the landscape, with the Master Thay clutching one or two children’s hands.

Normally, the kinhin line circles the outer edge of the practice room or, for smaller groups or individuals, a 15-20 pace extended loop, down and back the space.

When the Dharma entered China, it entered the territory of Taoist masters. Over the centuries, the two flowed in and through each other, leaving invisible links and overlaps. Like roads built over roads built over roads, no one can say what the substance of the final road may be. We pause to meet walking Tai Chi, a unique and companionable form of walking whose meticulousness and rhythm can teach us a new side to our walking.

Chapter 6: Journey 2 – Crossing

Evening the pace, feeling the freedom from former ways, we slip into the walking of our ancestors, all those monks who wove back and forth across the sandy trails between a deer park, a king’s palace and a wealthy man’s garden. Readily we come to appreciate the delights and demands of a meal on the trail. We are now immersed in a new life.

Walking Practice 2: Walking as Daily Life

Anyone who has passed a day at a Dharma centre will have engaged in samu practice. This term from Japanese Buddhism will have parallels in other countries. It refers to all the day-to-day duties a monk or retreatant undertakes to contribute to the Sangha. It is almost a stereotype of samu to be sweeping floors or cutting wood. The variations are as many as tasks in place. Virtually all of these require some walking. We will examine what we can bring to these work-practices. Only a few of us will pass much time inside a temple or monastery walls compared to the hours we spend at work elsewhere. We explore how we can make these periods of work opportunities for practice.

Walking Practice 3: Alms Rounds

No doubt, the oldest formal Buddhist foot practice is that of alms rounds. As Shakyamuni assembled his steady group of followers, they adopted the already accepted practice for wandering ascetics, that of daily visits to homes and estates to exchange the presentation of teaching, for some material contribution, most often food and drink. This is not begging, in the sense of someone down on their luck asking for support from someone more materially successful. Alms rounds are a recognition of the intersection of two distinct competencies. Those with material goods exchange them for the receipt of salvational teaching by those who specialize in that knowledge. The religious are not seen as ‘needy’, but rather in possession of specially acquired knowledge. Since laypeople were viewed as incapable (at least in earlier times) of their own religious education, the gift of teaching was the primary way they could benefit from the efforts of clergy. (It was, in fact, part of Buddhist vows to make efforts to present the Dharma to other people.) Providing for wandering ascetics was, of course, a means of acquiring merit, good karma. How the spirit of this walking practice can be transformed for our modern situations is an as-yet answered question we will ask.

Chapter 7: Threshold 2 – Turning Back

At some point, every walker must decide to transform the walk from a letting go to a coming back. We will take time to reflect on the symbolic and ritual meaning of this moment, what we previously called our journey’s liminal or threshold moment. With our time behind us increasing, we come to appreciate the path-builders, the trail setters who preceded us. We understand their sincerity and effort, and will feel some gratitude. We turn to practices that represent that appreciation and thankfulness.

Walking Practice 4: Circumambulation

Circumambulation, for Buddhists, derives from the practice of walking around some sacred or honoured site. As part of the practice of venerating the remains of a great teacher, practitioners performed a walking and recitation practice which slowly encircled the stupa, in a clockwise manner. The recited material would be a familiar chant or a sutra. Such a practice not only deepens the practitioners mind-practice, but generates merit for themselves and others. Doing circumambulation is an essential part of any Buddhist pilgrimage.

Over time circumambulation around stupas or pagodas became possible around other sites, relics or statuary. In modern times, in its most extravagant form, it begins to merge with pilgrimage walking as circumambulation around sacred mountains becomes a practice.

Walking Practice 5: Walking Nembutsu

Nembutsu is a practice which emerged later in Buddhist history and is characterized by a reliance on a direct personal relation between the practitioner and a Buddha figure, most often Amida, the Buddha of Infinite Life and Light. It understood that human history had moved through an era where it had been possible for individuals to achieve Buddhahood by their own effort (jiriki), and entered a more decadent era (mappo) where it was necessary to rely on the intervention and effort of the Buddhas, that is, Other effort (tariki).

Because practitioners had to rely on super-human intervention, it became necessary to not only honour those figures, but also to request their generosity to aid struggling humanity. The new form of practice was this prayerful and personal plea for the Buddhas to employ their power to accomplish the work of Liberation. The address to Buddhas became the practice of nembutsu. The Jodo sects became the earliest formalization of this practice, although it found a home in other schools, especially Tendai, and even Zen.

Such entreaties could, and ought to, be made in and through every action. Nembutsu practice most frequently looked like extended chanting and silent prayer services. One version combined devotional chanting with walking practices. In some instances this would overlap or even replace sutra chanting during circumambulation. In others, it was a new practice form, that of walking nembutsu.

Prayer Walking

As modern walkers, we can draw on modern walking practice. One of the most popular is Mundy’s ‘prayer walking’. We will meet this Christian preacher and experience how his methods add a new devotional dimension for us.

Chapter 8: Journey 3 – The Long Road Back

Once our footsteps have turned to home, that stage of the journey may, in different moments feel the longest and the shortest part of the walk. We feel a growing eagerness to regain the familiar, yet resist abandoning this road and its freshness and richness. We can admire and imagine joining the millions who made the longest walks their practice.

Walking Practice 6: Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage, within Buddhism, likely existed from the time following the physical demise of Shakyamuni. With the appearance and promotion of stupa practice, it must have become desirable for early Dharma followers to re-trace the travels of Shakyamuni as part of the adoration of his physical life. Itinerant ascetics were nothing new in Northern India during that period, Shakyamuni himself was but one of countless, nameless men who left the relative comfort of towns and courts to explore the meditative life.

As Buddhadharma began its steady march, along the legendary Silk Road, across Asia into China, Korea, Japan and Southeast Asia, it set up a ‘supply-chain’ back to the great monasteries of India. There are many tales of monks returning to India to retrieve versions of sutras, rupas and other learning materials. Once these East Asian Sanghas became established, it became similarly important for Japanese monks to travel back to the home monasteries to retrieve teachings, sutras and religious objects for their own national centres. The giants of Japanese Dharma, Kobo Daishi (Kukai), Dengyo Daishi (Saicho), Dogen and many more, made the dangerous return trip to the Chinese home-base of Dharma.

With the establishment of Dharma centres at a national level it became more common and desirable for practitioners to undertake pilgrimage to places of importance. Pilgrimage in the Buddhist context is not different in form or in intention from those of many other faiths. It is a substantial endeavour for any practitioner, one that separates them from their normal routines, placing them on a super-temporal plane, a kind of symbolic level where their daily activities interpenetrate the cosmic realm of great human or super-human figures. In past times, pilgrimage was a dangerous and life-altering experience. In our world of rapid transit, high-speed rails and roads and helicopter charters, the risk has been dramatically reduced. Yet the symbolic importance of leaving one’s life to become a pilgrim offers unique opportunities for practitioners.

Walking and Bowing

No doubt, greeting bows, the simple physical honouring of the Dharma in the presence of another, would be part of a monk’s daily routine. The practice of formal prostrations, a structured sequence of bowing, is a well-established one in Dharma history, although one which needs coaxing for Westerners. Not only is there little tradition of bowing or prostration, there is overt resistance and hostility to the idea of even bowing to anyone or thing, let alone a full-out prostration. There are various styles from the more elegantly restrained Chinese-Japanese style to the all-out stretching prostration of Tibet. We won’t take too much time to discriminate these differences here. We will describe the different styles and consider how to blend them in with a walking practice, be that indoor or outdoor.

Walking Practice 7: Kaihogyo and Kokorodo

Kaihogyo has been called the greatest physical challenge for human bodies, far more demanding than Western marathons. It belongs within the Tendai sect, and consists of rapid-paced daily walks, extending approximately eighty kilometres, up and down a steep and risky mountain route. Very few people ever receive authorization to undertake the training or perform the practice. It is an undeniable inspiration for all walking practices. It is, however, not something the majority of Dharma practitioners would even request.

We will not detail here, nor encourage this practices for most practitioners. Kaihogyo requires a substantial support-team, that is the involvement of many other monks, and, at certain stages of the practice, a whole lay community, to enable the completion of a super-human and life-threatening effort. It is not our purpose to facilitate such practices.

Kokorodo can be seen as a conflation and scaling back of both pilgrimage and kaihogyo. Not everyone can dedicate years or resources to daily marathon walking, or weeks to following a pilgrimage route. The kokorodo is an abbreviated version of these practices, where individual or groups of practitioners can share the endless road. It can be a taste of kaihogyo/pilgrimage experience that fulfills some of the same purposes. It removes the practitioner from the daily routine, even if that is a routine of a stationary retreat, and moves them into that symbolic/cosmic realm of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. The ordinary events of a 20 mile walk become transformed into an expedition into Dharma realms and heavens where century-old trees become encounters with sage-kings and Bodhisattvas; passages through cemeteries become confrontations with the intersection of life and death.

Unlike kaihogyo, the route may be familiar and less associated with great Dharma legends. It does not demand the rigour and repetition of kaihogyo, nor does it demand the extended commitment of pilgrimage. But like a pilgrimage, the practice may be a similar separation from daily routines and relationships.

Part III: In-Between Spaces

The metaphors of walking as journey, as crossing have been steadily with us to this point. Here we display a second powerful metaphor, that of walking in in-between spaces. Borrowing from another modern writer, novelist China Miéville, and his novel, The City and The City, we learn how walking can expose for us new dimensions in-between our day-to-day lives and spiritual realms which they parallel or intersect.

Chapter 9: Journey 4 – New Walking

As we see the landmarks that promise home, we begin to reflect on all the walks we’ve taken, their forms and benefits. Walking now enters a new realm – the symbolic. We envision and map out future walks into that realm. We expand our perspective and make connections previously unmade with other walkers. With the early Christian seekers we enter one of many labyrinth courses. Recalling the author whose words and walking passion opened our journey, we ‘saunter’ with Henry Thoreau along his beloved Marlborough Road, to where it intersects with the roads of our world. Finally, we find new meaning and enthusiasm for the walks which have been chosen by our present Dharma family to transform our world.

Walking Practice 8: Walking a Symbolic Landscape

The preceding practices all demand some amount of physical exertion and take place over a real, natural landscapes. The practices of this chapter take us into the realm of largely symbolic and less physical travels. Mandala and Pure Land visioning have deep roots within Dharma practice. Labyrinth practice is largely foreign to Buddhist experience. It is included here because, as a foot practice, it offers a great deal to Dharma practice, and because it is becoming increasingly familiar to Western practitioners.

Walking the Stations

Another version of a symbolic walk, in fact, a kind of symbolic/mini-pilgrimage is the structure of the Stations of the Cross. We’ll pass up and down the church aisles to experience the possibilities of this important Christian walk.

Mandala and Pure Land

Mandala are symbolic patterns, sacred landscapes which describe realms, personages and relationships which invite us into another level of experience where we can participate in processes and adventures beyond the confines of usual time and space. Such experiences can supercede our ordinary body-bound experience and lead us to new understandings of the activities of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. We will examine several noteworthy mandalas and their associated practices.

Pure Land recitation and visualization refers to meditative expeditions wherein the practitioner enters into a trans-physical landscape, one created through the meditative experience, and explores the otherwise inaccessible landscape of the Pure or Western Land of Amida Buddha. In these travels, we follow the practitioner who creates/enjoys a visit to an idealized world of sublime perfection, one intended to inspire and structure one’s human realm practice. We consider how we can walk to such a land ‘in this very life’.

Walking Practice 9: Labyrinth Walking

Labyrinths appeared in Mediaeval Europe, and possibly earlier, introducing Christian and pre-Christian symbolism into a highly structured walking practice. As Lauren Artress, the woman who single-handedly restored knowledge of and interest in the labyrinth, notes:

The labyrinth is like teaching a fish to swim. It is easy and natural for most people to enter into a different realm of consciousness.

The Sacred Path Companion, Artress, p. 25

Labyrinths are fixed-pattern walks, typically circular, which lead the walker through a complex series of back and forth circles which are designed to interrupt usual-mind thinking. One cannot predict the movement through a labyrinth, but one always has the confidence of completion. Labyrinths are not mazes. They require no solving, only walking. While they have little historical relation to Dharma practice, they have become familiar enough to Western practitioners that there may be value in learning to use them for Dharma practice. We follow our own footsteps through different shapes with different intentions, perhaps to find a way to blend this practice with our own.

Walking Practice 10: Sauntering with Henry

Thoreau has inspired countless writers, naturalists, meditators and environmentalists. During the middle of the 19th century, he re-located from a bustling commercial town in the North East of the US, into a small cabin not far, but far enough, from the town so that he felt part of a natural landscape. His reflections on his life, on nature, on civilization and on walking helped shape 20th century values and thought. In his book/essay, Walking, which first appeared in 1862, he begins:

I have met but one or two persons in the course of my life who understand the art of Walking, that is taking walks, who had a genius for ‘sauntering’… I think I can not preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day at least, and it is commonly more than that, sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.

Walking, Thoreau, p. 1-4

There is a distinctly ‘spiritual’ tone to Thoreau’s work and so, as contemplative sojourners ourselves, it will be instructive for us to walk some way with him.

Walking Practice 11: Walking for Change

Many of the various waves of Buddhadharma arising in the West have tended to replicate Eastern practices. Contemporary Western Buddhists have carried on most of the traditional walking practices in some form. With the maturing of Buddhist thought and practice, teachers of all traditions found it critical to re-form walking to meet the needs, issues and familiar context of modern Western society.

From the worker’s marches of the early 20th century, through the protests of the 60’s-80’s and into the 21st century, walking has found a place in the repertoire of social change advocates. Buddhists, East and West, have lead and joined marches for many causes, most often with peace and environmental issue focus. One radical and imaginative new form for walking is interpreted in Elias Amidon’s Mall Mindfulness. He explains:

[I had decided to invite my students…] to try something new – to contrast the grounded wisdom achieved through walking mindfully in non-human made nature with the lessons revealed through walking mindfully in that temple of human-made nature, the shopping mall.

Mall Mindfulness, in Dharma Rain, p. 232

No less participants in this disjointed modern world, we can bring the historic adaptability and creativity of Dharma practitioners the world over to our engagement in the process of bettering our planet and society. Walking can be a vital element of that activity.

Chapter 10: Returning Home

Home, and the journey is over. And yet, are we at the end or only locating ourselves at another threshold? Can we ever truly dwell without some awareness of another boundary which we must cross, and the journey which will take us there? What have we learned on our travels? How might we begin or transform a personal practice with our new walking experience? Will the prospect of some new adventure thrust us into the company of that 17th century Zen poet-traveller, Basho, who could scarcely shake the dust from his feet before he abandoned his cottage once again for The Narrow Road to the Deep North.

Let us make preparations for our journey.