Читать книгу Staging Citizenship - Ioana Szeman - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

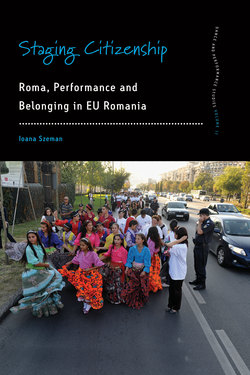

‘Roma Culture’ Clashes: The State, the EU and Roma NGOs

ОглавлениеThe Romanian government’s ten-year National Strategy for Improving the Situation of Roma (NSISR), 2001–2010, funded in large part by the EU,18 failed to acknowledge that Roma were first and foremost Romanian citizens.19 The NSISR was a public policy document focused on several guiding principles, including decentralization, consensus, equality and identity differentiation. It prioritized ten development directions: community development and public administration, housing, social security, healthcare, justice and public order, child protection, education, culture and religion, communication, and civic participation.20 The official recognition of the Roma minority did not lead to legislative power for Roma, unlike for other ethnonational minorities in Romania. In 2010 there was one Roma politician from the Roma Party for Europe in the Romanian parliament, representing up to two million Roma21 in Romania, while a similarly sized Hungarian minority had twenty-two members of parliament in the Hungarians’ Democratic Union Party.22

This citizenship gap has been maintained through the historical appropriation and erasure of Roma culture, which in Romania has resulted in the perception of the Roma as cultureless (a situation exacerbated by the former socialist regime’s complete denial of Roma as an ethnocultural minority). Despite official recognition of Roma culture, in post-socialist Romania Roma are seen as both uncultured – individually and collectively – and lacking folklore (a proper tradition) or high culture.23 On the one hand, the Romanian state recognizes Roma ethnoculture, but on the other it does not provide Roma with the kinds of ethnocultural institutions that support ethnic minorities of a similar size. For example, national minorities such as Hungarian and German Romanians enjoy state-sponsored ethnocultural institutions, including schools and theatres. There are no state-sponsored ethnocultural institutions for Roma in Romania, with the exception of the National Agency for Roma (the most recent iteration of the only government institution explicitly charged with coordinating public policies for Roma, which was founded in 2004) and the recently opened Museum of Roma Culture, an important and long-overdue institution.24

I define Romania’s state-sponsored multiculturalism as normative monoethnic performativity, which includes the cohabitation of separate, non-intersecting ethnocultures, as illustrated by the Hungarian minority’s successful lobbying for an autonomous education system (see Vincze 2011). The dominant essentialist understandings of identity create a system of non-intersecting cultures and parallel worldviews modelled on monoethnic nationalism and favouring ethnocultures that are also nationalities, such as Hungarian or German; this system continues to appropriate and erase Roma culture, failing to treat Roma culture as equal to other ethnocultures. One becomes Romanian or Hungarian by attending monoethnically denominated Romanian or Hungarian schools and dance ensembles, whereas Roma children from Pod, for example, continue to be stigmatized, and many attend special schools for students with learning disabilities.

During post-socialism Roma culture has resurfaced as a paradigm for Roma ethnicity, but not through public cultural policies. Instead, Roma culture has become visible in commercial and NGO representations, and neoliberal approaches to culture have converged with nationalism and xenophobia in the commodification of identifiable Roma cultural aspects that do not challenge nationalist paradigms.25 The official recognition of Roma culture has thus become a mechanism of exclusion based on authenticity criteria that pigeonhole Roma into stereotypical images.

Current policies for Roma have promoted narrow definitions of culture that exclude the most impoverished. Cultural and social programmes for and about Roma focus on what makes Roma stand out from the majority: traditional occupations such a tin making, spoon making and playing music. For example, the 2002 Roma Fair held outside the Museum of the Romanian Peasant, in Bucharest, featured Roma demonstrating a range of traditional occupations, few of which are practised today. Such exotic images of Roma tradition and ahistorical cultural paradigms directly influence who is recognized as Roma under EU-guided neoliberal social policies. Official definitions of Roma communities, such as those used in EU programmes for social change among Roma, conceive of Roma in these terms, failing to take into account the current lives of most Roma, including the poorest. Poor Roma in Pod, for example, express and take pride in Roma culture, despite not fitting into officially sanctioned definitions of authentic Roma crafts, occupations or attire.

Social programmes sponsored by the EU and NGOs function as spaces of misrecognition for many poor Roma, and recycle Ţigani stereotypes: Roma are recognized by the state as activists if they possess the high culture Roma are supposed to lack, and if they can fashion themselves into self-sustaining individuals showing self-reliance.26 Paradoxically, even as they recycle underclass stereotypes, social programmes for Roma are training activists in ‘civility’.27 The process of NGO training has turned activists into neoliberal subjects and cast some Roma, like those in Pod, as inauthentic. Obliged to operate within paradigms that equate Roma culture with tradition and authenticity, Roma activists are called upon by the state to demonstrate their own modernity by casting ‘authentic’ Roma as timeless and traditional and distinguishing them from the undeserving poor. In this way, poor Roma have been constructed as the abject Other, while exotic Roma have gained a new popularity that sits easily next to existing stereotypes.

In order to close the citizenship gap for Roma, monoethnic national paradigms, cultural policies and the official writing of national history need to be changed to include them. While I show that NGOs often contribute to maintaining the status quo of monoethnic performativity, the mushrooming of Roma NGOs – which Trehan defines as the ‘NGO-ization of Roma rights’ (2009, 56) – allows possibilities, albeit limited ones, for a critique and redefinition of citizenship. I use the term ‘NGO historiography’ for the alternative historical narratives that have foregrounded Roma, challenged ethnic-based definitions of Romanian citizenship and have been produced or disseminated through NGO events, institutions and initiatives. NGO historiography has to compete with the hegemony of the monoethnic nationalism promoted and supported by state institutions. It produces narratives that function as minor histories28 (Stoler 2009) that challenge and cut across simplistic, victimized versions of the nation; national histories in the region have emphasized the negative effects of powerful empires and the annexation of national territories. I analyse the work of Roma activists under the constraints of neoliberalism and nationalism, and document their attempts to change hegemonic national paradigms to include Roma, regardless of class, gender or occupation, in definitions of citizenship and national history.