Читать книгу Staging Citizenship - Ioana Szeman - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Outside the Archive/the Outside Archive: Consuming Roma Culture in the Marketplace

ОглавлениеThe 2002 Roma Fair, entitled ‘Mahala şi Ţigănie’ (‘Slums and Gypsydom’) included a wide range of participants, both Roma and gadge: Roma activists, artists, students, Roma craftspeople from across the country, prominent and lesser-known musicians, magicians, Roma businesspeople and leaders and so on. Jointly organized by the Resource Centre for Roma Communities, and the Mircea Dinescu Poetry Foundation under the auspices of the European Commission and the Romanian Ministry of Culture, it was not an exclusively Roma event, and the prominent Romanian poet and intellectual Mircea Dinescu was one of its organizers.

Inside the museum, the fair occupied the foyer, where launch events for academic and literary books were held, including the memoirs of the magician Maria, Queen of White Magic. The book exhibition featured works by Roma scholars, such as: Roma Slavery in the Romanian Territories, an important work of NGO historiography edited by Vasile Ionescu, one of the organizers from the Roma association Aven Amentza; volumes of poetry by Roma poet Luminiţa Cioabă, who was present at the fair; and the Bible in Romani. In the room designated ‘Laolaltă’ (‘Together’), which hosted temporary exhibitions on minorities, the exhibition ‘Între o Del şi o Beng’ (‘Between God and the Devil’) provided a historical timeline of the Roma presence in arts and culture. There was a Roma NGO forum in one of the larger auditoria, and a Roma student ball playfully entitled ‘O Soarea la Mahala’ (‘An Evening in the Mahala’). The museum courtyard hosted an exhibition of traditional Roma crafts and several open-air concerts, with bands from across the country performing under the banner ‘Muzică Lăutărească Veche’ (‘Old Lăutari Music’).

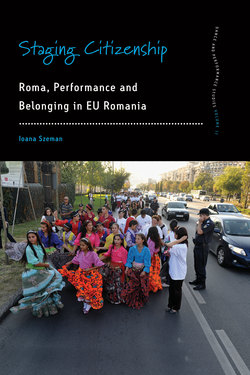

As one stepped into the museum courtyard, where Roma of different denominations were selling objects, ranging from costumes to household items, among the transplanted peasant houses that constitute the museum’s permanent fixtures, there was a sense of a return of the repressed in the very heart of Romanian nationalism. Two Kelderara women with ribbon-woven plaits and colourful outfits proudly stood in front of a table displaying similar garments (see Figure 1.1). They were selling long pleated skirts and matching blouses made of a patchwork of multicoloured fabrics – red, green, blue, yellow and purple. Each skirt had two layers: one, wrapped around the waist, covered the body, and the other, apron-like, lay on top. The blouses were also very colourful, short and very loose, almost like skirts for the upper body. Browsing the stall alongside many other visitors, I was shocked to find that the asking prices for single garments ranged from 50 to 100 euros: the average monthly wage in Romania at the time was roughly 100. The women were evidently targeting Western tourists, or newly rich Romanians who had acquired Western habits and Western pockets. At the next stall, two long-bearded, long-moustached silversmiths in wide-brimmed black hats were demonstrating the art of jewellery making. Further along, a few young women in urban clothes were offering their services in white magic, described in the fair brochure as divination and palm reading. On the left-hand side of the yard, Kelderara men dressed in urban clothes were displaying huge copper containers of various shapes, popular in Romania and used for the home brewing of alcohol. These Roma wore modern attire and were visibly well off, with Kelderara men and women alike wearing gold chains, big gold rings, and large gold earrings for the women.

Figure 1.1. Kelderara Roma selling outfits and copper pots at the Roma Fair, Romanian Peasant Museum, Bucharest, October 2002 (photo by Ioana Szeman).

Figure 1.2. Kelderar Rom on the left and Rudara selling wooden household objects (right); in the background the stand of the Kelderara, and a television reporter. Roma Fair, Romanian Peasant Museum, October 2002 (photo by Ioana Szeman).

On the right-hand side, placed more marginally and with fewer visitors, several women dressed in subdued colours and dark scarves were selling garments that looked nothing like the Kelderara outfits and seemed identical to the peasant garb exhibited within the museum: white shirts, long white gowns with coloured embroidery, dark scarves and so on. The asking prices for these items did not exceed 20 each. Across from these women, woodcarvers wearing dark trousers and coats and black hats were selling wooden spoons, bowls and pots (see Figure 1.2). Unlike the Kelderara, these participants did not conform to popular depictions of Roma. I identified them from the official brochure as possibly Rudara.

The live demonstrations at the fair were part of the Programme of Revaluing Traditional Roma Crafts, which brought ‘traditional’ crafts and craftspeople to the Museum of the Romanian Peasant. The fair brochure identified the live demonstrations as a first stage in a larger programme designed to adapt traditional Roma crafts to the demands of the market economy and ‘improve tools, working techniques and product development’ (Roma Fair Guide 2002, 1) – a possible survival strategy, and an avenue for the development of the larger Roma community: ‘Furthermore, the utilitarian character of these crafts could undergo a shift, in the sense of acquiring an artistic character endowed with an ethnic marker, and thus become a form of reassessment of Roma cultural heritage and an affirmation of Roma identity’ (Roma Fair Guide, 2002, 2). The brochure listed the following occupations, with illustrations: blacksmiths, coppersmiths (Kelderara), silver- and goldsmiths, welders, woodcarvers (Rudara), brick makers, tanners, comb makers, brush makers, bear handlers, horse traders (Lovara), fiddlers and magicians. The fair itself featured coppersmiths, silversmiths, woodcarvers, magicians and fiddlers.

I asked one of the woodcarvers about his occupation and showed him the brochure. He told me that he was not really a Rom, but welcomed the opportunity to sell his work at the fair. I asked one of the women selling the peasant-style costumes about the shirts, skirts and gowns on display in front of her. She said that she was a Rudari, not a Romni or Ţiganca, and that she had inherited the clothes, but she was not sad about putting them up for sale as long as she made good money from them. She said that if she told people she was a Rudari, few would understand who she was; and rather than risk being taken for a Ţigancă, she preferred to be mistaken for a Romanian peasant.

Economic differences among the participants were reflected not only in their attitudes towards Roma identification, but also in their self-confidence and market knowledge. The common denominator ‘Roma’ covered multiple groups that engaged in the so-called traditional occupations listed in the brochure. The presentation of the live demonstrations as part of a fair with merchandise for sale favoured some occupations and Roma groups over others. The simple garments of the Rudara failed to live up to expectations of authenticity and attracted less visitor attention. Kelderara showed the most distinctive features that ‘branded best’ in relation to the commodification of ethnicity in neoliberal capitalism (Comaroff and Comaroff 2009). Indeed, Kelderara metonymically replace the common denominator ‘Roma’ in popular perceptions: their costumes and artefacts are the most recognizable and most cited in other instances of identity commodification, from Gypsy soaps to music and ethnic chic. At the fair the Kelderara clothing underwent the shift mentioned in the brochure, from utilitarian objects to artworks, and sold successfully – not simply as ethnic ‘Roma’ markers, but as ethnicity itself.

The Kelderara artefacts and products that enjoyed the most success at the fair became ethnocapital, a means of both self-construction and sustenance (Comaroff and Comaroff 2009). Whereas visitors inside the museum had to wait to reach the museum shop to purchase merchandise, at the fair they could buy directly from the stalls. This process, which combined recognition as a minority with consumption in the marketplace, reflected identity formation processes during post-socialism. Heritage represents culture named and projected into the past, and simultaneously the past congealed into culture (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, 149). This understanding of culture equally pervaded social programmes that sought to revive the utilitarian character of traditional occupations along with training for other types of income-generating activities, as I show in Chapter 3.

The Roma themselves are absent from official histories in Romania, and for them the past is veiled by their construction as living in a continuous present, without care or concern for the past. Recognizable, lucrative stereotypes facilitate the continued forgetting of Roma history. As the Comaroffs show, ‘identity, from this vantage, resides in recognition from significant others, but the type of recognition, specifically, expressed in consumer desire’ (Comaroff and Comaroff 2009, 10). The incorporation of Roma culture as ethnocapital through its most recognizable and distinctive aspects has not only responded to market demand, but has also become compatible with ethnic nationalism in Romania through commodification.

Offered temporary shelter inside and outside the museum, which told the story of the ethnic nation and its folklore, the fair exceeded national paradigms. Both indoor and outdoor events at the fair were temporarily hosted by the ‘archive’, represented by the museum itself – from which the Roma had been excluded, even while elements of Roma culture had been appropriated. The place of the museum was anchored in hegemonic narratives supported by the state, whereas the fair was a temporary space.2 For those who cared to listen and pay attention to the contradictions in the ostensibly seamless narrative of the museum, the fair wrote minor history by combining the archive and the repertoire, using archival evidence of Roma history while foregrounding the living cultures of diverse Roma.

The Rudara objects and costumes were less successful in the marketplace than the Kelderara because the Rudara artefacts looked similar to the Romanian peasant outfits displayed inside the museum. While the museum’s hosting of the fair emphasized the distinction between what was inside (the Romanian peasants and their traditions) and what was outside (the Roma and their occupations and costumes), the Rudara disrupted this clear separation dictated by normative monoethnic performativity, and made apparent the arbitrariness of official definitions of the Romanian folk versus Roma culture. The display of almost identical items inside the museum and outside at the fair, under different denominations and prices, was thus a strong statement about the similarities between some Roma (such as Rudara) and Romanian peasants, and about the processes of cohabitation and mutual influence over centuries. Rather than inserting a rupture between Romanian peasants and Roma craftspeople in the guise of Self and Other, the Rudara and their costumes suggested a continuum along which different ethnic identities could be placed and contextually self-identified, always in relation to one another.

The Museum of the Romanian Peasant as an institution has excluded any other ethnicity and established a monocultural history of the Romanian nation. A minor history approach reveals precisely how multiplicity and multivocality – lived experience in a multicultural context – have been translated into a univocal narrative of the nation at the museum.