Читать книгу Staging Citizenship - Ioana Szeman - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Minor Histories: From Slavery to the Holocaust

ОглавлениеThe speech cited at the opening of this chapter is illustrative of a more widespread attitude among the Romanian political class towards the Roma minority: the formal embrace of European policies on Roma on the one hand, and the absence of their practical application on the other. More specifically, the speech reflects the treatment of Roma history, where the acknowledgment and discussion of little-known aspects such as the Holocaust or Roma slavery do not lead to a change in national paradigms based on ethnicity. Similarly, legislative changes to end discrimination against Roma have not altered national institutions and their discriminatory practices. The President’s plea for EU money at the end of his speech indicates an expectation that, as far as he was concerned, the Roma in Romania were the EU’s responsibility.

President Băsescu’s speeches over the years reflect the evolution of some sections of the political class’s attitude in Romania. The post-socialist diversity discourse, a result of Romania’s EU negotiations, slowly gained traction in political rhetoric and reflected a change in direction for some politicians, from inflammatory rhetoric regarding Roma to a more ‘politically correct’ attitude. Many journalists viewed Băsescu’s 2007 Roma Holocaust speech with suspicion as a pre-election campaign manoeuvre, with the photo shoot featuring the President flanked by the three survivors, politicians from the Roma Party, and Roma King Florin Cioabă, a Kelderara leader from the Sibiu region. Journalists reminded the public that only a few months previously the President had called a female journalist a ‘stinking Ţigancă’ because she had insisted on getting an answer from him in an unsolicited interview. Faced with international pressure, the President apologized for using an inappropriate phrase in public, but made no mention of the racial slur or sexist remark. Roma NGOs considered the apology inappropriate.3 A few years before this incident, when Băsescu was Mayor of Bucharest, he called for Roma to be placed in ghettoes outside cities.4 These examples show that politicians’ convenient adoption of a progressive rhetoric has entailed little in the way of treating Roma as equal citizens.

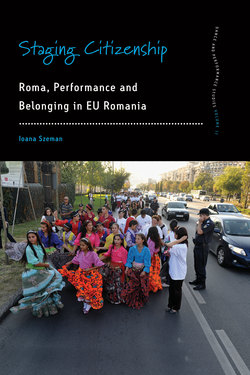

In 2010 the Romanian Senate debated a proposal by Roma activist and scholar Vasile Ionescu and the Roma Party to mark the end of Roma slavery with an annual commemoration day and to include Roma slavery as a topic on the general school curriculum. The senators – all of them non-Roma – rejected the proposal. (In fact, Senator Paul Hasoti proposed ‘Ţigan’ as an ethnonym to be used instead of ‘Roma’. He claimed it was not a pejorative term, as it meant ‘alien’ and could equally be found in other languages.5)The Romanian Senate’s initial rejection of the emancipation commemoration day is a reflection of the privilege of the majority and the refusal to grant Roma the right to define themselves. Eventually the proposal was accepted and passed into law in March 2011, and 20 February became Emancipation Day. Roma activists annually celebrate Emancipation Day with commemorations and public events. Like the Roma Fair, these events tell a story that is uncomfortable and incompatible with the logic of monoethnic nationalism. However, these public events address and engender growing counterpublics that do not share the nationalist paradigm. As long as they take place in public spaces tolerated and sanctioned by the state, these events’ radical potential can be either heeded or ignored, depending on the participants’ perspectives. As Floya Anthias (1998) has argued in a British context, the true test of multiculturalism is not adding ‘cultures’ devoid of historical and social context, but renouncing hegemonic symbols and paradigms. For non-Roma in Romania, the true test of inclusivity is the confrontation with the self beyond binary definitions of Self and Other, and the willingness to listen to counternarratives that might be uncomfortable or seem inflammatory at first.

Despite the President’s urging (cited at the opening of this chapter) that schools should teach about the Roma Holocaust and slavery, only Roma students learn about them. In general, the curriculum teaches optional courses on Roma language and culture to Roma students only. Unlike in Hungarian and German schools, where the whole curriculum is taught in the respective language, Roma students are taught mainly in Romanian. Despite recent publications and the reappraisal of Antonescu’s role in Romanian history, the curriculum does not teach the fact that the Romanian state was responsible for the deportations of Roma and Jews from Romanian territories. For example, during an International Roma Day celebration I attended in 2008, the exhibition outside the performance hall displayed documents about the Holocaust and explained that the German state had sent Roma to concentration camps; the Romanian state was not mentioned. Furthermore, only Roma students attended the celebration. Discussions of Roma slavery are equally controversial as those of the Holocaust, if not even more so, because in the case of slavery it is difficult to shift the blame onto other nations: the owners of Roma slaves were Romanians – royals, monasteries and nobles. Collective accountability is absent from national history narratives, where the victimization and resistance of the nation are the main motif.

A focus on Roma history as minor history entails undoing victimized images of the monoethnic nation and breaking open the binaries inherent in its construction. There is no centralized place, in the sense of an institutionalized location (de Certeau 1984), for writing Roma history, even within one country; but the many Roma communities’ diverse perspectives are often seen as arising from their own lack of unity and coherence, rather than from a lack of centralized institutions. For example, the presence of different words in Romani for the Holocaust, such as ‘Porrajmos’ (‘the Devouring’) (Hancock 2006), also spelled by some Roma as ‘Pharrajimos’ (Bársony and Daróczi 2008) or ‘Samudaripen’ (‘Murder of All’) (Cioabă 2006), point to the many perspectives from which Roma history is written, and reinforce the importance of considering national and transnational perspectives simultaneously when discussing these events.

Roma activists, artists and intellectuals have published oral histories and archival research and created documentaries and artworks that break the silence on Roma history, challenging national histories that present the Romanian nation as a victim of the Nazis, Communists or earlier empires while excluding Roma and Jews. Oral histories and testimonies have revealed the marginalization and neglect of survivors upon their return home from concentration camps and other places of deportation after World War II. Prominent Roma poet and activist Luminiţa Cioabă (2006), in an oral history project with Roma Holocaust survivors, has shown that many survivors did not have the know-how to successfully apply for the compensation to which they were entitled.

Despite the fact that the complex history of and around World War II has been reappraised and rewritten many times, including after 1989, the Roma Holocaust is little known, and not only in East Central Europe. Across Europe, the Roma Holocaust – a result of ‘racial science’ and an attempt to completely annihilate the Roma during Nazism – was the most extreme moment in a long history of Roma marginalization. The 1935 Nuremberg racial laws involved ‘mixed’ Gypsies’ incarceration and sterilization on the one hand, and ‘pure’ Gypsies’ group resettlement and ‘species preservation’ in special camps on the other. Prisoners in the separate Gypsy camp at Auschwitz were assigned the most debilitating labour (Trumpener 1992, 855). In Romania, one of Germany’s allies during World War II, authorities implemented similar anti-Roma policies, including the deportation of 25,000 Roma to Transnistrian labour camps after confiscation of their belongings. The deported included all nomads and the majority of sedentary Roma. Those who survived the harsh camp conditions returned to Romania after the war (Achim 1998).

In East Central Europe, national narratives reproduce binaries of Self versus Other, binaries exacerbated by fascist and Communist ideologies. In Romania, Communist-era World War II historiography focused on the anti-Nazi victory; since the fall of Communism, history has been rewritten with a strong anti-Communist ethos. The reshuffling of hero/villain roles between Communists and Nazis after World War II conveniently displaced any blame from the ‘nation’ while portraying it as the victim of either of the two extremist ideologies. The new heroes of the nation after 1989 were anti-Communists or local fascists who may have fought against Communism, such as Marshal Antonescu, who ordered the deportation of Roma and Jews in Romania. Pressure from Jewish communities has put an end to what was becoming a national admiration of Antonescu, who sent tens of thousands of Jews and Roma to their deaths.

The pictorial display inside the museum at the 2002 Roma Fair, ‘Între o Del şi o Beng’, was an exercise in NGO historiography. It aimed to offer ‘an image-based excursion through the material and spiritual aspects of Roma culture in its happy or miserable interaction with Romanian culture, from social fracture to resolidarization and intercultural dialogue’ (Jurnalul Naţional, 2002, 1). The display included exoticized representations of Roma by non-Roma. Such bohemian representations of Gypsies need to be approached cautiously, and to be treated as artistic conventions rather than as historical referents. In the nineteenth century, Gypsies became a favourite topic for Western artists, who projected onto them their own condition as outsiders in an increasingly mercantile society (Brown 1985). Romanian artists joined this trend, portraying exotic and beautiful Ţigănci who were often presented as lustful and oversexualized; some of these portraits featured in the exhibition. The oversexualized and idealized images of Roma women on display were also similar to current representations in Gypsy soaps on television.

Through an invocation of the past, this display at the fair offered a critical analysis of such representations by juxtaposing them with historical documents about slavery and the Roma Holocaust. From a minor history perspective, the juxtaposition of Roma representations by non-Roma with historical documents about slavery and the Holocaust cuts across the forgetting of Roma history and critiques the stereotypical representations of Roma. However, by exercising their hegemonic ignorance, visitors could still enjoy the consumption of Roma culture and images that complied with neoliberalism and globalization and that maintained the citizenship gap for Roma.