Читать книгу Raw Life - J. Patrick Boyer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One

ОглавлениеThe Venue: From Dirt Floors to the Gay Nineties

Muskoka District, land of First Nations peoples for over five thousand years when Canada’s incomparable explorer David Thompson mapped the place in 1837, was traversed by fur traders and surveyors in the early to mid-1800s, but only felt the hard edge of intrusion with logging along its southern perimeter in the 1850s and land settlement a decade later. Construction of crude colonization roads opened the way for early arrivals. Then the trickle of settlers turned into a flood after Ontario’s legislature, wanting to entice more newcomers to fill and farm the empty tract, enacted The Free Grant Lands and Homestead Act in 1868. The result was a land boom.

The exhilarating promise of a fresh start in life drew many improbable settlers to this wilderness frontier. An anxious jumble of characters abandoned their problems and set out for Muskoka to start anew on their hundred acres of “free” land, hoping to cash in on a promise Ontario’s government and its immigration agents were aggressively promoting through advertisements in American and British newspapers and in the booklet Emigration to Canada: The Province of Ontario, circulated widely in 1869 to publicize Muskoka’s glowing agricultural prospects for new settlers.

Few heading to Muskoka sought a transformation more complete than a desperate thirty-five-year-old lawyer who, early one September morning in 1869, boarded the train in New York as Isaac Jelfs, but stepped off in Toronto as James Boyer. Accompanying him was a pregnant woman, their little girl, a curly-haired teenager, and another woman in her early twenties. Nobody could have mistaken this formally dressed family group for pioneer settlers heading into Muskoka’s wilds to hack a homestead out of dense forest. Yet, such was their intent.

Not only was Jelfs abandoning his name. He was forfeiting a long-craved legal career with the politically influential Broadway Avenue firm of Brown, Hall & Vanderpoel. He was relinquishing his recording secretary’s role with the Episcopalian Methodist Church in Brooklyn. He was abandoning the vice-presidency of the Brooklyn Britannia Benevolent Association, an office to which he’d been glowingly elected in May that year, being presented with a copy of Byron’s poetical works and making, as the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “one of his happy speeches on the occasion.”

The real kicker was that he had closed the front door of the Jelfs’s18th Street family home in Brooklyn for the last time. Overnight Isaac vanished from the life of his wife, Eliza, and their young daughter, Elizabeth. The pregnant woman on the train, Hannah Boyer, was not his wife in law, but had become a second wife in reality after she’d captured Isaac’s heart at a Britannia Benevolent Association Saturday night dance several years before. The two-year-old girl on the train was their first love child, Annie, whose birth the couple had discreetly left unrecorded in New York’s registries. Equally absent from official documents was any record of their marriage, since neither in New York nor later in Canada would they ever have a legal wedding. James and Hannah and their affiliated family travelled by train, boat, stagecoach, and boat again to at last reach the village wharf in Bracebridge and their new life.

“Mr. and Mrs. James Boyer” had quit a bustling, overcrowded, foul city to enter a pristine wilderness, whose thick silence was punctuated only by bird songs, the hollow rushing of quiet breezes in tall pines, and the steadily comforting sound of crashing waterfalls. Muskoka’s pure air had special buoyancy, its dampness releasing the pungent earthy muskiness of fresh wood and mossy rock, a swilling mixture with heady evergreen scents made even fresher by breezes crossing the district’s rocky expanses and crystalline lakes. Bracebridge itself, a stark settlement barely a decade old, was a tiny scattering of shacks, tree stumps, and rough, muddy pathways, isolated, primitive, and much further from New York than all the miles the Boyers had journeyed to get here.

Hannah and James Boyer settled in Macaulay Township, east of Bracebridge, where he soon set about clearing land for farming. James cherished the remoteness, as did other settlers resolved on escaping their pasts. His New York years had simply been the latest chapter in a life buffeted by fate so poignantly that Edward Greenspan remarked, “The tale of his life’s journey would not be out of place in a Charles Dickens novel, except that James’s story is not fictitious.” Greenspan believes “the chapters on James’s life are essential to this book.” Yet the telling of his story and of the equally stirring, entwined saga of Hannah Boyer would require more space, to do their story justice, than can be accommodated here. So it will appear as a separate volume entitled Another Country, Another Life.

In 1868 Bracebridge was designated district capital because of its geographic centrality, and soon several provincial government offices opened to serve the entire Muskoka territory, which not only contributed to the settlement’s growth, but also helped establish the community’s character as the centre for Muskoka government and administration of justice. Muskokans, irregularly scattered across a large and rugged landscape with poor transportation and rudimentary communication, recognized the emergence of a central hub. In Bracebridge itself, these officials and courts faced plenty of work sorting out the human and economic hodgepodge emerging from Muskoka’s raw opening phase.

In the larger picture, the provincial policy of building colonization roads and offering free land had served its intended purpose. The district was being populated and settlements were growing.

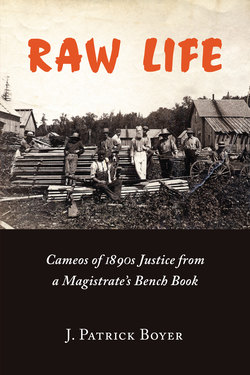

Clear-cut logging created drab open space for the emerging settlement of Bracebridge, seen here in 1871, two years after the Boyers arrived from New York. The Muskoka Colonization Road enters this picture from the right, just after crossing the Muskoka River, then turns north to become the village’s main street. The Northern Advocate newspaper, which James Boyer edited, was the first publication in Ontario’s northern districts.

As the settlement grew, the usual aspects of civil society developed. Protestants in early 1870s Bracebridge had the choice of salvation through Methodist, Presbyterian, or Anglican churches. By mid-decade a Roman Catholic priest took up residence in town for the first time — the beginning of another flock. Adherents not only headed to worship services segregated into their respective denominations, but enjoyed community entertainments sponsored by their particular churches.

More broadly, social life was becoming organized: members of the Orange Lodge had a meeting hall; the children, a school; and adults, the Mechanics’ Institute library and its reading room with newspapers and periodicals from Toronto, New York, and London. This Mechanics’ Institute, which began to operate the community’s first library service in 1874, was a worthy institution for Bracebridge. A Mechanics’ Institute was the best available structure for organizing a community library in those days, since free public libraries had yet to emerge. The first Mechanics’ Institute in Ontario was formed at Kingston in 1834, and other larger centres in southern Ontario had since created community libraries this way as well.

The Muskokans of the 1860s and 1870s were different from the immigrants arriving in southern Ontario in the 1820s. The earlier settlers, recalled by historian Robert McDougall, were often “the bungs and dregs of English society,” characterized by their poverty and illiteracy. Those reaching Muskoka a half-century later were, in much greater proportion, educated and entrepreneurial. Just as McDougall recognized in the former their “sterling qualities of character” that made them “the muscle and sinew of the new civilization” emerging in the province, he saw how a smaller number of educated and literate immigrants amongst them gave the emerging community “its mind, its taste, and its voice.”

The fact that Muskoka remained closed to settlement until the 1860s meant it had been held in reserve for later waves of settlers, whose social and economic status and levels of education gave the district strong minds, decided tastes, and outspoken voices. This historical sequence contributed to differentiating Muskokans from others in earlier-settled southern Ontario. Many of those coming to settle Muskoka between the late 1860s and 1880s were more accustomed to modern ways and had higher expectations for themselves than did the earlier settlers, but their fresh start in life required more of them: not just a pioneering encounter with raw land, but also a struggle with the rude conditions on the Canadian Shield. The exchange was bound to produce a particular character.

Bracebridge itself is a river town, and the waterfalls have played a central role in its development, not only powering its early grist, lumber, and shingle mills, but forcing into existence a local economy based on transshipment of goods: moving cargoes from steamboats to horse-drawn wagons, and vice versa, because the falls were a barrier to water-borne transport further upstream into the Muskoka interior. The waterfalls and river also inspired construction of facilities to accommodate travellers and their needs, because the natural setting of the town attracted visitors who enjoyed its scenery despite the stumps and mud. Soon the town site was dotted with hotels and taverns, on both sides of the river.

During Muskoka’s navigation season, which could stretch to eight months, steamboats from Gravenhurst brought freight, mail, and passengers to Bracebridge Wharf. The Muskoka River’s falls at Bracebridge marked the upper reach of Muskoka River navigation and made the town the main transshipment centre between boats and wagons for Muskoka’s north-central interior, a local advantage that lasted until the railway came through in 1885, continuing to Huntsville and beyond.

As its economic activity and commercial trade hummed, Bracebridge emerged as a central hub, not only for government offices and legal administration, but also for the movement of people and cargoes by river, by road, and, after the Grand Trunk Railway reached the place in 1885, by rail.

Agricultural settlement in the townships around Bracebridge, in the spots it could flourish, added a farming economy to this mix, advanced by the early presence in Bracebridge of a grist mill. Next, businesses selling farm equipment and supplies emerged, followed by the formation of an agricultural society and the holding of fall fairs to inspire improved farming methods and better animal husbandry.

Pioneer William Spreadborough’s wife stands behind the fence while he and their four boys are out in front. The family’s hard work and pursuit of quality are displayed in their cabin: logs squared and interlocked at the corners, a sloping and shingled roof, framed windows with curtained glass panes, and the fence built of split rail.

General economic development created a demand for labourers, millwrights, woodsmen, factory-hands, and teamsters. Several more tradesmen were arriving in Bracebridge each year. All the while, the forestry economy in Muskoka was keeping several thousand hard at work logging, droving, and milling. In the process, Muskoka was achieving a diverse mixture of peoples with a wide range of skills and aptitudes, many with strong backs, a large number with intelligent minds, all propelled by stubborn determination.

Although people enjoyed robust life in a natural setting, fitting their activities rhythmically with the district’s alternating seasons, the ever-present hardships and toil made Muskoka an inhospitable and unnatural home for malingerers. People did not come to the frontier to claim land or work in a mill expecting a frivolous escapade. A few were able to get by doing little work; these were rich rascals, the “remittance men” sent to Muskoka by socially prominent British families to remove their embarrassing presence from respectable society, but at least the money sent out, or remitted, to them in the distant colony helped Muskoka’s cash-short economy. Another plus was how a number of these dandy misfits added lustre to the community’s arts and letters clubs and early drama societies.

England also contributed to Muskoka’s population mix from its poorest classes. Here again the British adopted an out-of-sight, out-of-mind approach, “solving” their social problems by merely shipping them overseas: prisoners to the penal colony of distant Australia, orphans and street urchins to the farms of Canada. Thousands of “orphans, waifs, and strays” were shipped to rough and rural pioneering Canada where struggle awaited them. Muskoka had the highest concentration of these “home children” child labourers — so named because they came from homes for orphans — thanks to the district’s settlement and development between 1870 and 1930 coinciding exactly with the duration of a deportation program emptying out the orphanages, poor houses, and slums of the “Mother Country” into Britain’s colonies. Many fetched up as indentured child labourers on the farms of Muskoka’s townships, most badly exploited, unschooled and unsupervised, overworked and underfed, melding into the economic underclass that was forming in rural Muskoka on farms that barely sustained those living and working on them.

Decades later, William E. Taylor, himself the son of an eleven-year-old orphan who laboured as an indentured home boy on a Canadian farm, explained that these youngsters were sent “in a mixture of intense confusion, terror, child courage and, occasionally, optimism. They absorbed the shock of early Canada, cultural and geographic; lived a grinding pioneer life we can now barely comprehend; fought, died, or somehow survived the holocaust of trench warfare; struggled through the Depression and in turn, watched their own children enter another war.” Taylor noted how greatly “their lives and thinking contrasts with the current Canadian mood of self-pity and dependence.” These world-wise and stoic children, who grew into adulthood and in most cases formed Muskoka families of their own, constituted another component of the human wave that reached the district during its settlement years and melded into the hard-love sentiment typifying Muskokans.

Wherever or however they lived, Muskokans needed goods and services, and enterprising settlers were establishing a supply to meet demand. By the early 1870s, services available to people in Bracebridge and its surrounding townships included those of a doctor, notary public, conveyancer, druggist, music teacher, and several land surveyors. Among the community’s tradesmen could be found a house builder, carpenter, window glazier, butcher, and baker. There was the post office, a newspaper, a blacksmith, the stage coach service, and hoteliers, each in their way helping people communicate and travel.

This rutted mud roadway had pole fences to keep cows out of gardens and people walking in the darkness of night on the path. The log barn at right would have been damp and dark, with its flat un-drained roof, tiny window, and dirt floor. The cabin, with chimney, sloped roof, and boards covering the dormers, was a typical dwelling of Muskoka homesteaders.

A number of retailers had also opened their doors to offer specialty lines of furniture, musical instruments, boots and shoes, leather supplies, groceries, dry goods, and clothing. In the heavier end of things, still others offered threshing and separating machinery, shingle making, lime and lathe sales, grist milling, and the services of a sawmill. For those who suddenly packed it in, coffins were available in Bracebridge, “made of the latest style and on short notice.”

Such enterprises and services were also emerging in Huntsville, Gravenhurst, and other comparable Ontario towns of the day. Something rarer in Bracebridge was its woollen mill, established at the falls by Henry Bird in 1872. It rapidly became an important part of the town, helping to guarantee the progress of Bracebridge and the success of the many hard-pressed Muskoka farmers who’d discovered with chagrin that their patch on the Canadian Shield was too rocky and swampy, with soils too thin, to serve for traditional farming.

Some other towns had woollen mills too, but two things that gave Bird’s Woollen Mill a unique place in Muskoka’s development were its added impacts on agriculture and resort vacations. The booming mill needed huge supplies of wool. Rocky Muskoka farms, unsuitable for crops, were ideal for grazing sheep.

Bracebridge industry soared when Henry Bird built this woollen mill by the falls in the early 1870s, giving a lift to Muskoka farming in the process. Sheep on the district’s rugged lands produced wool for his mill and famous “Muskoka Lamb” for the dining rooms of summer resorts and big city hotels.

Henry Bird made generous arrangements with financially strapped Muskoka farmers to raise sheep, provided they sold their wool only to his Bracebridge mill. At the same time, Muskoka was experiencing the emergence of hotels and lodges for visitors. Distinctive and handy, “Muskoka Spring Lamb” became a menu specialty in their dining rooms. Muskoka’s new sheep farmers made lucrative arrangements with the district’s enterprising hoteliers to supply both fresh lamb and mutton. As soon as train service connected the district to the country’s larger centres, these born-again farmers began meeting the demand for Muskoka’s now-famous spring lamb in major hotels across Canada too.

Bird’s Woollen Mill also became a major manufacturer of woollen products, selling its famous “Bird Blanket” across the country and abroad. The mill’s substantial stone facilities would be expanded a number of times, the company remaining a large employer and economic mainstay of Bracebridge for the next eighty years.

An equally crucial industry that came to both Bracebridge and Huntsville was leather tanning. Once Bracebridge became incorporated, elected representatives began exercising their new ability to speak officially for the village with interested businessmen about establishing new factories and manufacturing arrangements. As a result, within just three years the Beardmore tannery was up and running, giving Bracebridge a still larger base on which to continue building up its substantial economy.

Once again, Muskoka’s farmers benefited enormously. Companies operating Muskoka’s tanning businesses became major buyers for their animal hides and an equally ready market for the vast quantities of tanning bark they stripped from hemlock trees and shipped by wagon and barge to the riverside facilities in Bracebridge. As with those now raising sheep, the fact many of these hardscrabble farmers lacked rich soil or flat fields was beside the point for this kind of “agricultural harvest.”

Economic development, with parallel growth of community services and facilities for the people, had, like Muskoka itself, many ups and downs and rocky patches. One early setback came with a blighting economic downturn in the mid-1870s, a by-product of the significant recession that gripped the U.S. during those years. In 1874 the council of Macaulay Township (in which Bracebridge was located) attempted to overcome the stagnation by granting a five-year exemption from municipal taxes to sawmills, flour mills, woollen factories, and foundries. Such extraordinary measures were needed as incentive for economic development in Bracebridge, for, as author W. E. Hamilton, taking stock of the community in March 1875 said, circumstances had “knocked the bottom out of the institution of Bracebridge.” This activist response by local government leaders showed that Muskokans were not content to be passive. They believed the new society they were creating in the district would be what they made it, and that its success depended on their resiliency.

It had only taken a few years of the government’s settlement policy for Muskoka, effectively promoted by Thomas McMurray and James Boyer through the Northern Advocate, to fill the district with pioneer

Cutting white pine and “clearing the land” challenged even the most determined Muskoka homesteaders, who sometimes had to plant in patches around the stumps until they could remove them. Muskoka’s soil was often just a thin overlay on bedrock; where deeper, it could be ploughed, but the blade often caught in roots of the felled pines.

farmers. By 1877 the whole of Macaulay Township east of Bracebridge was taken up. All but five of the most marginal lots in the township were occupied. Generally, this was the pattern in most Muskoka townships accessible by colonization road or boat. Once free-grant lands were no longer available, a new settler could only get a farm by buying it from an original homesteader, or from the Crown if an original claim had not resulted in a patent of land.

Many homesteaders found Muskoka farming more than they’d bargained for. If asked what crops they had, they’d reply “growing stones.” Cramped farm fields, first cleared of the forest, then freed of their stumps, next began sprouting rocks, which were forced to the surface by frost and by ploughing. The Boyers, in common with most settlers on the Canadian Shield, found that much of their farming time was spent harvesting not vegetables but boulders, using their horse to pull, not a wagon loaded with hay to the livery stables in town, but a stoneboat loaded with rocks to the edge of their field.

Often too many large stones made the effort of hauling them to the edge of the field unbearable. Weary farm families simply formed additional mounds throughout their fields. After several years, these painstakingly piled stones resembled taunting grave markers in a burial ground of their owners’ aspirations.

In 1875, when the settlement of Bracebridge was incorporated as a village separate from lots in the surrounding townships, the newly elected council voted to appoint James Boyer first clerk of the new municipality. Being in the village, rather than near it, would benefit all concerned. After six harsh yet memorable years as Macaulay homesteaders, the Boyers looked forward to modest comfort, closer to others. They were slightly less concerned now, after the passage of time, about being unmasked. The community had come to accept them as a married couple.

In May 1876, using money from selling “the homestead farm,” Hannah purchased a small frame house at the north end of town. The Boyer house at 2 Manitoba Street was on the west side, about fifty yards from where, seventeen years earlier, the lone pioneer John Beal had built a humble squatter’s shanty as the settlement’s first dwelling. The colonization road, which subsequently passed Beal’s front door, causing the loner to relocate to more remote Rosseau, had been named Manitoba Street, just as other principal thoroughfares had been renamed Dominion, Ontario, and Quebec streets, to express Bracebridge’s soaring patriotism.

The land at the rear of the Boyers’ house, sloping gently to the west, was soon filled up with garden vegetables in summer and snow in winter. Two blocks east, a gurgling spring formed a pond, from which Hannah and the children harvested watercress in summer and fetched buckets of cold clear water year-round. They bought raw milk fresh from a farm nearby.

They would live in this house for the rest of their lives. In all, Hannah and James produced seven children. After Annie, born in New York, and Nellie, William, and Charles, who first saw the light of day in Macaulay Township, came another son, George, born on July 21, 1878. He was followed by Bertha, who arrived on October 20, 1880. The last child, a son named Frederick, was born May 5, 1883. William died when only nineteen

In this 1890s scene outside the Boyer’s modest frame house on Manitoba Street at the north end of Bracebridge, James disappears into a book while Hannah shows daughters Annie and Nellie, in white blouses, a detail about her stitching. Of the Boyers’ three sons, George stands, Fred holds “Spot,” and Charlie is absent. Sometimes a town constable or an aggrieved party would appear at this front door at night or during a holiday and “speedy justice” would be dispensed by Muskoka’s justice of the peace.

months, in November 1875. Bertha lived just eight weeks before disease carried her away on December 17, 1880.

The Boyer family attended the Bracebridge Methodist church, which James had joined on moving to Muskoka, seeing it as a reasonable alternative to the Episcopalian Methodist Church he’d belonged to in Brooklyn, and the best choice, given his views and character, among the limited options available. He soon became secretary of the Methodist’s cemetery board, and served as a church trustee. Hannah was similarly active in the Methodist church and its women’s organizations, living “a consistent Christian life,” as her son George put it, “doing her duty to her family and neighbours and to her church faithfully and well.”

Church was not all about duty, though. The real magnet of Sunday service was the music. James loved singing in the choir. His ever-expanding collection of books included many volumes of church music. James also played clarinet and flute, sang bass, and delighted in having his family sing Handel’s Messiah. The rest of the family was equally musical. Son Charles was especially gifted, and a great dancer as well. Son George, who would begin teaching barefoot pupils at a rural one-room Macaulay school by age sixteen, was leading the Methodist church choir in Bracebridge by nineteen, and singing the soprano parts, or at least the air, until his voice changed.

Bracebridge was filling up with families who, like the Boyers, were leaving their outlying bushlots. Having given it a good shot, and putting in enough time to qualify for their free land grant, they now sought something better than scratch farming. So, many now came to town, hoping to improve their fortunes there.

However, a number of those who abandoned their bushlots wanted out of Muskoka altogether, hoping never to return. Those who caught “Manitoba Fever” went west, where they hoped for better Prairie farms. A decade later, others would head deeper into northeastern Ontario to farm “the clay belt” around Cochrane, where millions of acres of fertile flat soil had been discovered: a farmer’s paradise hidden within a seemingly endless landscape of muskeg and exposed bedrock. Over the same period, many more departed for the always-beckoning United States, either returning to New England or the Midwest from which they’d come, or heading west, drawn to the coast by California’s allure.

One such man was Robert Dollar. He had been one of the Boyers’ neighbours while they lived on the farm. He had prospered in Muskoka’s lumber business, and had risen to a position of influence in the community, serving on Bracebridge council, where he worked closely with his neighbour, the village clerk. In one outing to the polls, however, Councillor Dollar suffered electoral defeat, losing by three votes. In the face of such voter ingratitude, he quit Muskoka for California, where he developed the ocean-going Dollar Steamships Line and became a millionaire.

James engaged in conveyancing work at the Land Titles Office, and in January 1871 had been appointed first clerk of Macaulay Township. But just six months after starting this municipal work, a human dynamo blew into his life — Thomas McMurray, who had started the Northern Advocate, the first

Finding six men to pose for a photo in the mid-1880s was as easy as setting up the camera outside Bracebridge’s busy Crown Lands office, hub of real estate transactions and property registrations, where James Boyer conducted his active land conveyancing practice.

newspaper in the northern districts. He wanted James to edit the publication. James accepted McMurray’s offer, and from 1871 to 1873 the Northern Advocate became James’s main focus. His job as editor was one that he was ideally suited to, because a primary mission of the weekly was to promote settlement under the free-grant lands system. He’d learned of the program in New York, was now benefiting from it, and was keen to promote it to others. He gathered reports from successful Muskoka farmers and published, at McMurray’s behest, a great deal of “practical information” to help new homesteaders. The Northern Advocate was sold in Muskoka, but also distributed widely in parts of the United States and Britain. The same information was also published in book form, The Free Grant Lands of Canada, giving McMurray another “first”: the first book published in the north country. The start of a competitor newspaper in Bracebridge, the Free Grant Gazette, and McMurray’s overextension of his financial resources in building offices for the town’s main street at the time of the mid-1870s recession, led to the demise of the Northern Advocate. With its closure, James Boyer returned to his position as Macaulay Township clerk.

Whatever their impact on individual fortunes, the recurring boom and bust cycles of capitalist economies eventually created an economic upswing that pulled Bracebridge into recovery. By the end of the 1870s, William Hamilton was able to report: “There was as a general thing much of bustle and life in the village, owing to the lumber traffic and the large number of immigrants on their way to locate on free grants or to purchase farms.”

The bleak irony in this good news was that many newcomers had learned of these opportunities through the promotional book The Free Grant Lands of Canada and the widely circulated Northern Advocate, but by incurring the financial outlay of building stores and offices in anticipation of the prosperity the settlers would bring to town, the visionary entrepreneur Thomas McMurray had been unable to hold on long enough to take advantage of the newcomers’ arrival and the return of good times.

By the end of the 1870s, Bracebridge’s population had climbed to a thousand inhabitants, and the village hummed with its many small factories, most financed by the Bracebridge bank owned locally by Alfred Hunt. The town’s citizens were kept up to date and politically aroused by two rival local newspapers, the Liberal Gazette and the new Muskoka Herald, which upheld Conservative interests.

Bracebridge continued to benefit from the fact that it was a natural home for mills of all types, which were operated by the waterpower of the falls, and for factories that were dependent upon large supplies of freshly running water. The town’s early industry — the flour mill, lumber mills, and shingle factory, later joined by the woollen mill and leather tanneries — was now augmented by a match factory, a furniture factory, brickworks, a cheese factory, a buggy shop, blacksmith shops, and livery stables.

The initial Beardmore tannery, reorganized as the Muskoka Leather Company, was now flanked along the riverbank below Bracebridge Bay by the sprawling Anglo-Canadian Leather Company’s tanning facilities. Local tanning would continue to expand until the companies combined production made Bracebridge part of the largest leather-producing operation in the British Empire, using hides imported from as far away as Argentina. All that was required for this pre-eminence in the leather economy, apart from hard work by tannery labourers and continuous harvesting of tanning bark by local farmers, was acceptance by all concerned that the Muskoka River downstream from the facilities would be outrageously polluted, filled with dead fish and the bodies of shoreline creatures that had perished — all killed by the stinking vats of fouled tannic acid emptied into the river’s waters.

Despite “Manitoba Fever” and the exodus of a number of farming homesteaders, the district continued to receive new arrivals. Employers were attracting tradesmen for jobs in mills and manufactories. As the population grew, Muskoka began to acquire more in the way of enriching cultural and social institutions.

Amongst the latter were the many local chapters of loyalist societies and fraternal lodges, bodies set up to reinforce the adherence of their members to familiar causes in this unfamiliar setting, and to provide mutual support for one another in difficult times. These various societies and orders, lodges and associations, were not service clubs of the kind that carry out helpful community-building projects; their focus was looking to the well-being and support of their own members.

It was that attribute, in an era without government welfare or social assistance programs, that helps account for the presence of so large a number of these entities in places like Bracebridge, and why most enjoyed large memberships, quite apart from the grand causes they ostensibly stood for. Such rudimentary “welfare” as was available in Muskoka was mostly provided through local chapters of these non-governmental organizations, and by local congregations of churches, which likewise looked to the well-being of their own adherents, thanks to the unspoken pioneers’ pact of mutual self-help.

James Boyer became secretary of the Sons of England Lancaster Lodge, secretary of the Loyal Orange Lodge, and secretary of the Loyal True Blue Association. Besides carrying his note-taking supplies to these meetings, he seemed to bring positive energy, too. Accounts of his involvement with the Orangemen, whom he joined through Bracebridge Lodge No. 218 in 1876, refer to his “enthusiasm.”

The existence in this small town of so many loyalist societies, as well as the several parallel ones for women, in many of which Hannah participated, gave testimony to just how British-minded the Bracebridge community was. Increasingly embodying its identity as a dynamic frontier town on the rugged Canadian Shield, the town was still an inseparable piece of Canada, which, in turn, was an integral part of the British Empire. In the cities, towns, and villages across Canada, just as across the Empire’s numerous British countries and territorial possessions, the red-white-and-blue Union Jack waved from a thousand flagpoles. Pupils in small and scattered schoolhouses gazed in respectful awe at the red-coloured areas on the wall map that identified so much of the world as the British Empire “on which the sun never set.”

Bracebridge’s loyalist societies esteemed visible patriotism. James never wore a flower, except a rose in his lapel on St. George’s Day to honour the patron saint of England. Intermittently, as municipal clerk he included on Bracebridge council’s agenda the purchase of a flag for the use of the town. And while he knowledgeably addressed loyalist clubs on the Battle of Waterloo and generally displayed a scholar’s interest in British affairs, James also took his family to “the Glorious Twelfth” celebrations of the Orange Lodge where, after the parades, more palpable displays occurred as sun-leathered men circled drums in a field, beating them with such intense rhythmic frenzy the corners of their Protestant mouths foamed. That raw intensity, too, was part of the “patriotic” reality. When elections rolled around, the Orange Lodge could be sure to deliver voters, who invariably cast their ballots in support of the Conservative candidate.

Over the years James not only rose to senior ranks in all these societies, but also participated actively in other fraternal associations, like the Independent Order of Odd Fellows and the Independent Order of Foresters, as secretary and in other top offices. All these entities served to knit together the social fabric of Muskokans. They also served to create a bellicose culture that would militantly commemorate the Protestant victory at the Battle of the Boyne every July 12, embrace without hesitation the armed suppression of the Riel Rebellion, enthusiastically send young Muskoka settlers to their deaths in Britain’s war against Dutch settlers in distant South Africa, and raise an entire battalion, the 122nd, with district-wide support, for the four-year massacre in Europe that would come in 1914 with The Great War.

The culture and economy of Muskoka that had taken shape was not a stagnating one, however. The Boyers and the other early homesteaders and tradespeople who first settled the region were joined by visitors. Ontario government’s homesteading project, which simply aimed to open up Muskoka for farming, began to take an unusual turn. The arrival of adventuresome folk who made their way up the colonization road and around the lakes by small boats in the 1860s helped to transform the culture of the region and add an unanticipated aspect to the local economy.

Permanent settlers were joined by people who came to Muskoka not to start a new life but to refresh the one they already had. They did not want to clear the land and farm it but to hunt its woods for game and gaze upon its scenic splendour. They sought not to use the lakes and rivers to transport logs but to fish and boat for pleasure. The magic in it was that they came, not to try to make money, but to spend it.

Because Muskoka offered people the experience of being in a natural northern setting — one conveniently close to the cities of the south — the district found itself welcoming people who wanted “a Muskoka vacation.” Without the interaction of summer visitors and permanent residents, this new way of life could not have emerged, but the commingling of the two types of people added a dynamic new element to the character of Muskokans above and beyond the mixture formed from the interaction of lumbering, farming, and manufacturing activities. Henceforth, the term Muskokans necessarily embraced seasonal vacationers and permanent residents, because you could not have one without the other. The symbiosis of the two became a nuanced mixture of mutual dependence, friendship, and antipathy.

As the farthest place that steamboats could come up the Muskoka River before encountering waterfalls, Bracebridge and its wharf provided a major transshipment facility for central Muskoka. Wagons and coaches ran the steep slopes of Dominion Street, seen beyond the steamers, connecting passengers and cargoes with boat transport around Lake Muskoka and Gravenhurst.

Alex Cockburn would be called “the father of Muskoka tourism” because his steamboats, operating out of Gravenhurst, made vacationing at summer places on three of the district’s major lakes, whose shorelines often could not be reached by road, possible. Yet the men who created those lakeside lodges could also claim paternity, as could the settlers who opened the roads and built up the settlements with their stores and services, because tourists could not have visited the district unless settlers had already colonized it, even if just for a few short years. The two phases were not far apart in time. Muskoka’s first adventure visitors arrived in July 1860 and summer vacationing began soon after, incrementally becoming a more and more important part of the district’s development.

The vacation economy was not created from a single blueprint, but constructed piece by piece by the district’s permanent residents and their visitor guests. Homesteaders with disappointing crops found that if their rocky fields backed onto a major lake, they could make an alternative livelihood by opening their log homes to parties of fishermen. The transition of these homes from rustic homestead to summer resort was a product of a mutual exchange between the cabin dwellers and the wealthy sportsmen who came to stay in their accommodation. Families would vacate their beds, put fresh straw ticks on them for the guests, and move into a shed to sleep. The small parties of sportsmen were content with a couple of square meals a day at the family table. Each adjusted to the other, and learned from each other, as their standards and expectations evolved. If the initial experience was a happy one, the following year an entrepreneurial homesteader might advertise space available for sportsmen, and when the anglers or hunters arrived, typically from the United States, they would discover an addition had been made to the cabin since last season, which now offered more space.

The names of these evolving early lodges epitomized their essential domestic character: “Cleveland’s House,” “Windermere House,” Francis and Ann Judd’s cabin, “Juddhaven,” and John Montieth’s place, “Montieth House,” all proclaim their true status in their names.

Over several decades a continuously upgraded range of accommodations emerged. Modest cabins became rustic lodges. Then purpose-built structures replaced cabins. Stuffed deer heads on lobby walls were replaced by oil paintings of Muskoka steamboats. Those at the vanguard created palatial lakeside homes and summer resorts with sloping lawns to the waters’ edge.

Such summer places were being replicated around all Muskoka’s main lakes, as farmers throughout the district learned to use their homes as resorts and their unpromising lakeside fields for tennis courts, lawn bowling greens, and golf courses. John Aitkin, who built up elegant Windermere House with his wife Lizzy Boyer — one of Hannah’s sisters who’d come from Brooklyn and lived four years in the Boyers’ Manitoba Street house before snaring the widower Aitkin — created Muskoka’s very first golf course.

Arrival of the Grand Trunk Railway in Bracebridge would boost and transform the local economy. Here the road gang blasts through rock in 1884 to create a level approach to the river, before bridging over the falls’ chasm.

Roads remained a challenge but the waterways offered convenient alternative transportation routes. The various types of watercraft that plied the lakes of the region offered a variety of benefits to guests, from elegant transportation to the pleasures of waterborne adventure. Once railways reached Muskoka, making connections to the growing fleets of steamboats, the district’s robust vacation economy became part of the Muskoka way of life. In vacation accommodation, just as in land settlement, the democratic district was open to anyone who came, offering humble cabins, easy accommodation for families wanting leisure, and elegant spaces of luxury for plutocrats.

As Muskoka grew and evolved, James Boyer continued as steady pilot of municipal affairs in Bracebridge. Depending on the mayor and council, some years were better than others. Bracebridge’s local government was generally progressive, providing electrical services and clean water, subsidies to attract new industries, and pushing for new and better public buildings.

By the late 1880s, the village had grown enough to qualify as a town. In 1889, when his private-member’s bill to incorporate Bracebridge as a town was passed by Ontario’s legislature, Muskoka MPP George Marter sent a telegram to the town office. Clerk Boyer relayed word of the new

In 1894 Bracebridge became the first municipality to own and operate its own electricity system, buying out a private power plant and propelling the town’s economic surge with clean, cheap hydro-electricity for the motors of industry and better lights for homes, shops, and factories. By the end of the 1890s, demand for electricity in town led to construction of Bracebridge No. 2 generating station at the foot of the falls, completed in 1902.

municipal milestone being reached to town constable Robert Armstrong, who rang the town bell for a full hour as the community celebrated their new municipal status and their law officer’s stamina.

Major leather tanning facilities in Bracebridge and Huntsville helped Muskoka emerge as part of the largest tannery facility in the British Empire, with cow hides imported from as far as Argentina. In addition to creating many (often dangerous) jobs, the tanneries also provided Muskoka farmers with a new lease on life, buying hemlock bark from them to brew the tannic acid they needed to cure the leather. The money was a boon to the farmers, but the tanneries’ effluvia resulted in the two towns’ rivers becoming outrageously polluted.

Another major milestone in the development of Bracebridge was the creation of an electricity system for the town. Bracebridge became the first municipality in Ontario to own and operate its own electricity generating station. In conducting these developments, council took a leading role. Clerk Boyer, among other related duties, conducted the plebiscite by which ratepayers voted to raise funds for the municipal hydro-electric system. The electric works greatly benefited townsfolk and existing business operations: the installation of thirteen streetlights transformed the main streets downtown, allowing shops to extend their shopping hours into the evening, and increasing safety in the streets at night. Stores and workplaces acquired electric lights, then electric motors. A competitive advantage had been gained with the town’s ownership of the electricity supply. Bracebridge offered electric power at low cost to sweeten the deal for new industries it was competing with other Ontario municipalities to attract.

On October 12, 1890, James wrote Hannah, who was visiting her sisters in New Jersey, “There is talk of another very large Tannery in Bracebridge. I have written to the parties to meet the council tomorrow night.”

The town’s ensuing success in landing yet another leather tanning operation illustrates how the tight interaction of government and industry in Bracebridge helped municipal development. First, town council, when negotiating with David W. Alexander of Toronto to establish the tannery, offered a two-thousand dollar bonus as further enticement beyond the advantage of low-cost electricity.

Second, James, as clerk, drafted a bylaw for voters to approve the incentive payment, which they did in the plebiscite that he conducted. Third, it was decided that the new tannery should be on the south side of the river. But the piece of land, although increasingly a part of the town socially and economically, with the J.D. Shier lumber mills and Singleton Brown’s shingle mill in that same section, as well as a growing number of homes, was still legally part of Macaulay Township. So the town council and its residents immediately set to work to ensure that the necessary changes were made to bring that land within the town’s borders. On cue, residents in the affected area applied to Bracebridge for this section to be annexed by the town, council voted money to get the necessary private bill passed through Ontario’s legislature, and also offered $150 to Macaulay Township council if its members would help lobby to get the act passed, which they did. The act passed, allowing the town to expand further both in industry and territory.

It was a fine example of a working democracy, with the local council advancing interests that benefited the town and its people, the citizens being involved by appealing for annexation and by voting in a plebiscite, and the legislature holding a vote on its interest in the matter. Time and again, across Muskoka, this thoroughgoing democratic nature was on display, a direct product of the time of the district’s political formation and the kind of people who had come to build a new society for themselves.

Fortunate settlers, winners at land-grant roulette, discovered pockets of truly fine farmland in Muskoka’s intermittent valleys and flats. They prided themselves on good animal husbandry and crop practices. Their produce was shown for prizes in Muskoka’s many fall fairs. It compared well to the best in Ontario at other agricultural fairs in populous parts of the province.

Whether as the secretary, a director, or, by 1888, president of the Bracebridge Agricultural Society, and later as president of the Parry Sound and Muskoka Agricultural Society, James enthusiastically travelled, usually in the company of a fellow officer, to display Muskoka’s prize-winning produce. In successive years he appeared with bushels and baskets at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto, the Central Canada Exhibition in Ottawa, and the fall fairs at Owen Sound and Barrie, to put Muskoka farmers’ best products on show. This became increasingly important, he knew, because Muskoka was getting a lot of bad press as a stony nightmare for luckless farmers.

A good harvest of Muskoka hay required storing it from rain, wind, and animals; these men used ladders and pitchforks and piled it high outdoors to dry. For this impressive 1890s photograph, women donned Sunday clothes while men posed with a yoked team and atop a stack. The barn’s well-selected logs were squared at the corners, though not all were debarked; a fine shingle roof, and boards nailed up until the supply ran out, helped keep the interior dry.

In one letter home to Hannah from Owen Sound, James described himself as “terrifically bound up in fall fair work.” When a reporter favourably looked over the exhibit of Muskoka produce, he offered a proposition: “Good exhibit. If you pay me, I’ll write it up in the paper.” James was indignant, and “did not pay.”

It was no different in Toronto. In 1887 the Bracebridge Agricultural Society sent its president, Peter Shannon, and secretary, James Boyer, to exhibit produce at Toronto’s Exhibition. Both men were keen to show that Muskoka could be an agricultural contender despite what the district’s critics said. James, in a September 12 letter home to Hannah from Toronto, described the CNE praise Muskoka’s produce received. People discovered “a splendid exhibit” of prized entries from farms in all sections of Muskoka. “It was difficult,” James wrote, “to make some of the visitors believe that grapes (Lindley or Rogers No. 9), some bunches of which weighed 1¼ pounds each, were grown in the open air of

Livestock, baked goods, and farm produce were on proud display each September at the Bracebridge Fall Fair, as were townsfolk. The spacious agricultural hall housed prize-winning entries from kitchen and field, and offered a balcony view of the race track. The buildings at left and right are on Victoria Street, the house at left, atop the rocky hill, is on Church Street. James Boyer, proud booster of Muskoka farming, was for decades an officer of the Agricultural Society, including serving as president.

Muskoka.” One of the samples of wheat grown on light, sandy soil in Macaulay sold at the close of the Exhibition to an American for one dollar, a notable amount in that time. “Our Duchess apples are not beaten by any that are exhibited prizes. Both the Globe and the Mail wanted to be paid to puff our exhibit,” he concluded, “but Shannon and myself refused to pay them one cent.” Muskoka’s valiant farmers faced hardened newspapermen as well as hard land.

Bracebridge Public School, as it appeared in the 1890s. The windowsills and other stonework were made by James Boyer’s brother-in-law, Harry Boyer. The school bell at the top came loose one day, while being rung to call children in, tumbling heavily to the ground, missing James and Hannah Boyer’s son George by two feet.

The district was, of course, a mixture of topography and soils, and not everyone had located on good land. Some with marginal lands but an entrepreneurial nature successfully shifted to sheep rearing and wool production, others harvested lucrative tanbark and maple syrup from their trees, while still others shifted their land use to the cash crop of Muskoka’s vacation economy. Just as Muskoka as a whole had a mixed economy, most of its homesteaders operated mixed farms.

For many would-be farmers, though, the dream that first brought them into the district, when Muskoka was being promoted to immigrants for farming, had been shattered by their inability to fulfill even the minimum conditions of the free-grant system for acquiring title to their land. In 1886, although 133 persons were newly located on lots in the district’s townships that year, there were also 99 cancellations of grants for non-fulfillment of settlement duties.

Although many poor farms were abandoned, some families stayed on in unfavourable locations and sank to subsistence-level living. In this way, the agricultural experience in Muskoka over the decades of free-grant settlement was gradually producing, in addition to its success stories, an economic underclass. These people were living on poor farms but were too poor to go anywhere else. Quite a few homesteaders had

Trains running south through Bracebridge from Ontario’s northern hinterland or the Canadian West were so long and heavy they required two locomotives. At right, Bird’s Woollen Mill increases production for Canada-wide and British Empire markets.

burned their bridges behind them, in the manner of James and Hannah, so could not “return home,” but they could not afford to relocate to anything better, either. Looking beyond the front verandahs of the Muskoka lakeside resorts and tennis courts where genteel city ladies in long dresses laughed while tapping balls, Canada’s 1891 census takers found two-thirds of Muskoka’s people dwelling in rural areas, many of them destitute.

By the close of the 1800s, Muskoka, and its towns, villages, small settlements, and random, scattered farms at the southern edge of the Canadian Shield, had each assumed distinctive characteristics, attributes which contributed, as social historian G.P. de T. Glazebrook expressed it, to “the great variety that was Ontario.” Bracebridge in the 1890s was, like most of the province’s villages and small towns, intact with its own commercial and social life.

This view of Bracebridge, taken about 1902, shows the centre of town as it was by the end of the 1890s. The short-lived Hess Furniture factory, five-storeys high, on the left, is adjacent to a sawmill and lumber yard; the river is spanned by a wooden bridge to Hunts Hill; the train station (centre right) is busy with freight traffic; across the street from it is the Albion Hotel, which stood until 2011.

Manufacturing and commerce sparked life in Bracebridge as the dawn of the twentieth century approached. Here, Henry Bird’s Woollen Mill dominates the foreground, and the central business section of town stretches up Manitoba Street beyond.

Workmen and workhorses in early 1890s Bracebridge pause at a busy mill and lumberyard in the centre of town, above the falls. Log booms in the river await their fast-moving saw blades.

During the decade, the town’s population more than doubled, from 1,020 residents counted in the 1891 census to 2,480 recorded in 1901. By the end of the decade, tax assessment of town properties topped more than half a million dollars, at $504,633. The town had also incurred a debt of $44,000, with plebiscite support from Bracebridge taxpayers, to create Ontario’s first municipally-owned electricity generating and distribution system, and to lay pipes beneath the town’s streets for clean drinking water to reduce water-borne illness in the municipality. The yearly receipts of the town from taxes and fees added up to about $36,000.

Within three decades of the town’s pioneer John Beal arriving by canoe, Bracebridge had grown to become an economic centre despite the number of marginal farms in its surrounding townships. In 1890 the building of another vast leather tannery and the creation of a major park within the town exemplified the town’s twin pillars of economic development and vital cultural life. Both reinforced the robust sense townsfolk had of Bracebridge as a go-ahead community.

The possibilities continued to dazzle. By the 1890s James Boyer was secretary and a director of the Bracebridge & Trading Lake Railway Company, which aimed to build a railroad from Bracebridge east to Baysville and Lake of Bays, and west to Beaumaris and Lake Muskoka. Railways, including the transcontinental that passed through Muskoka, had become an exciting physical link with the wider world.

Canada counted for the biggest expanse of British red on the world map, and thanks to common political institutions and language, shared laws and legal principles, and even derivative English judicial offices such as the justice of the peace, Canada’s “British subjects” experienced what historian Carl Berger called “a sense of Empire.” Despite this conscious connection to grandeur on a global scale, the country as a whole consisted of fewer than five million people sprinkled over a seemingly endless territory. Ontario styled itself Canada’s “Empire Province,” and, at the start of the 1890s, boasted a population of 2,100,000. The population of Muskoka, which in 1891 was 15,666 and rose some 5,000 more by the turn of the century, was still a far cry from the millions of people promoters like Thomas McMurray had boasted would by now be prospering on their free-grant farms.

Despite this fact, life in Bracebridge, reflected week by week on the rival pages of the Grit Gazette and the Tory Herald, unfolded within a confident sense people had of being part of something larger than themselves. News and advertisements from the United States, reports of global developments, and accounts of national political events, all meshed seamlessly with local births and deaths, weddings and hockey matches, updates on crop prices, and advertisements seeking able-bodied harvesters to go west by train and bring Prairie wheat in from the field.

Queen Victoria, who had ascended the throne in 1837, the same year David Thompson first mapped Muskoka, was well into the longest reign of any British monarch, having herself become as much an institution as the Crown itself. Bracebridge had its Victoria Hotel, Victoria Street, and like most every municipality in Ontario, its Queen Street. In 1897 the agricultural society’s show grounds were renamed “Jubilee Park” to commemorate Victoria’s diamond jubilee.

The long political reign of the Liberal-Conservative Party in Canada under its wise and wily leader Sir John A. Macdonald, who helped form the country in 1867 with the creation of a new federal constitution, and then oversee its development with bold new national policies and the addition of Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, and British Columbia as provinces, was spluttering to its end. After Sir John A.’s death in 1891, which shocked the country not because he was an old man but because it seemed a Canadian institution had vanished, a succession of Tory prime ministers — John Abbott, John Thompson, Mackenzie Bowell, and Charles Tupper — held office before the Liberal leader, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, was elected in 1896. Laurier’s leadership in re-fashioning the Liberal Party of Canada and forming a “cabinet of all the talents” by bringing to Ottawa such illustrious provincial leaders as Ontario’s Premier Oliver Mowat began an historic shift in the country’s political alignments. All these events were fully reported in the local newspapers and discussed avidly in Bracebridge, a highly political town.

The 1890s stood as a high water mark for the British Empire. By the turn of the new century, Queen Victoria would be gone, another human institution vanished. Britain’s seemingly invincible military was bogged down in a war in South Africa that would extract a high price, as a relatively small number of resolute fighters in a faraway land stalled the world’s greatest military power in its tracks. Young Bracebridge men were transported to fight and die in South Africa because Canada was an integral part of the British Empire. For London this war was important, and in Muskoka emotions ran high in support of the blood-letting. Market Street in central Bracebridge would be renamed “Kimberley” Avenue after the South African city, and a triangle of land in the centre of town was designated “Memorial Park” for the sons of Muskoka settlers who died while killing Dutch settlers on their farmlands half a world away. The British proved as adept in drawing from their colonies healthy young men to die in their wars as they had been in dispatching to the colonies their troublesome dandies, convicted felons, and orphaned children — a two-way flow of traffic orchestrated by the benignly misnamed “Mother Country.”

Despite the carnage of the Boer War, the last decade of the 1800s would be popularly dubbed “The Gay Nineties,” capturing the open gaiety in society exuded by those able to enjoy life’s pleasures. Beneath the surface glitter of the Victorian era at its zenith loomed rawer reality.

With the arrival of another economic downturn as the final decade of the century began, doubts about the country’s viability resurfaced. In Toronto, Goldwyn Smith, journalist and renowned professor of economics, elevated such misgivings to hard-ribbed analysis in his book Canada and the Canadian Question, in which he marshalled economic, geographic, and political reasons for folding Canada’s brief experiment with nationhood into union with the United States.

In its celebration of life, the revels of the “Gay Nineties” offered a popular way to defy and transcend these social, economic, political, and military strains. Celebration was in the atmosphere of Bracebridge. Embattled individuals, who struggled in their circumstances and from time to time found themselves before Magistrate James Boyer, were otherwise at the band concerts, in the parades, and on the sports fields. Individuals experiencing rougher social conditions and the raw edges of life might not themselves have chosen the moniker “Gay Nineties” for their times, but then people in a position to name eras are seldom the threadbare folk living on hard energy at society’s margins.

In the predictable boom-bust cycle of a capitalist economy, the decade advanced from economic depression into a recovery. With general prosperity returning, many Muskokans did have a good time. Bracebridge newspapers ran accounts of local sporting matches, outdoor church services, visiting circuses, fabulous touring bands, fall fairs, community picnics, theatrical performances, and festive excursions across the lakes by boat, down the roads by buggy, and along the tracks by train.

In the struggle to overcome all of these ups and downs, Muskoka’s incomparable character emerged. From the opening of the settlement the district was a place of natural beauty, physical hardship, dashed hopes, sudden profits, irreconcilable conflicts, and new starts. The diverse peoples flocking from distant places to claim land were, year by year, increasingly re-formed by the land’s claim on them. It made them democrats and stoics.

Families had become homesteaders in a localized Ontario economy of mixed farming and wage labour in forestry, mills, tanneries, and manufacturing workplaces, integrated with facilities for transportation, accommodation, and services for vacationers. They dwelt on their rural acreages or in Muskoka’s main towns of Gravenhurst, Bracebridge, and Huntsville; the larger villages of Bala, MacTier, Port Carling, Rosseau, Baysville, Dorset, and Port Sydney; or the smaller settlements such as Walker’s Point, Windermere, Milford Bay, Utterson, Dwight, Falkenburg. These people lived amid rugged conditions and scenic splendour in the Canadian Shield’s northern hinterland but still close to the southern cities, witnessing changes for which they were both designer and creator, and of which they were sometimes beneficiary and other times victim. They were interacting alike with well-to-do folk trekking into the district for vacations, and edgy neighbours who were scrounging year-round just to get by.

Out of the rawness of this cauldron emerged a distinctive new variety of people, the “Muskokans.”