Читать книгу Raw Life - J. Patrick Boyer - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Three

ОглавлениеThe Stage: Magistrate’s Court in 1890s Bracebridge

In 1892 during the same decade as the cases in this book, Parliament brought new order to Canada’s criminal law and procedure by codifying countless separate statutory provisions into a single, comprehensive Criminal Code. Codification, a sensible approach long used by other legal systems but not the English, made Canada the first country in the British Empire to consolidate, integrate, and harmonize its legal regime governing criminal behaviour.

The landmark codification work was done by Judge Sir James Robert Gowan of Barrie, who had already become known to the public as one of the commissioners investigating the Pacific Scandal after it helped bring down the government of Sir John A. Macdonald. Now, for the intricate and profound challenge of thinking through the possibilities and implications when combining all existing criminal law and harmonizing all criminal procedure into a single statute, Judge Gowan carried out much of his demanding task in the pleasant surroundings of Lake Muskoka.

Gowan summered on a large island near the mouth of the Muskoka River named Hogg Island, which he renamed Eileen Gowan after his own family, using a Gaelic version of the word for island. The same island would also accommodate far-reaching discussions and decisions affecting law and justice later in the twentieth century as summer home to Honourable R. Roy McMurtry, who served over several decades as Ontario’s attorney general, solicitor general, and chief justice.

In clearing away the tangled legal underbrush and bringing rationality to the system as a whole, Gowan’s recommendations, when enacted by Parliament as the Criminal Code of Canada, helped clarify the long-standing practice of having many local justices of the peace available who could punish petty offenders, filter out frivolous or vexatious cases, and evaluate more serious charges.

In shoring up the power of JPs, the 1892 changes also removed from jurors the right to initiate an investigation if they suspected an offence had been committed, vesting that power instead in justices of the peace and other magistrates. That change was made by Section 557 of the Code, which also authorized JPs to be the ones to summon potential witnesses and examine them under oath.

The “rule of law” at ground level required that justices of the peace be readily available to dispense speedy justice. By quickly cooling hot disputes between neighbours or within families, resolving petty conflicts erupting along society’s outer edges, and meting out punishments to relatively minor offenders hauled before him by a local constable, game warden, or aggrieved neighbour, the front-line JP could thwart community lawlessness that otherwise would prevail.

Yet, while a JP could do this for many infractions, he could not do it for all. More serious offences were beyond the magistrate’s jurisdiction. Both before and after codification in 1892, graver matters were either heard by a judge or by a panel of several JPs. This concept had first emerged in England and was part of the system exported to Canada, as noted in the preceding chapter, and while the office of JP had evolved significantly in Canada, this requirement remained unaltered.

A pragmatic reason for JPs to sit in a panel of two or three for more serious charges was that these first-responders of the judicial system lacked legal background or special training for adjudication. Prudent public policy thus favoured a collective approach with shared responsibility, reducing the risk that a lone magistrate might run too far off the rails. Having a panel could be a safeguard for the rule of law.

A second practical reason for empowering several JPs to hear a matter that otherwise required a judge could easily be understood in places like Muskoka. Small towns, frontier settlements, and rural locales did not have nearby judges with jurisdiction to try these graver offences. In Bracebridge’s early years, when travel was arduous and took a long time, he was to be found sixty miles to the south, in Barrie.

Often the panel of JPs was authorized to make a judgment and impose a sentence itself, although in some instances their work amounted to a preliminary hearing after which they ordered that the case proceed to the nearest judge. Although James Boyer tried many cases alone, often one or two other JPs had to join him on the bench because of these rules. The more justices of the peace available, the easier it was to assemble a duo or trio, and the speedier justice could be.

Muskoka District, like the rest of Ontario, was actually awash in justices of the peace. During the 1890s no fewer than fifteen other men assisted James Boyer on the bench: Harry S. Bowyer, Singleton Brown, Robert M. Browning, Alfred Hunt, John Inglis, Charles W. Lount, John McDermott, E. Josiah Pratt, Peter M. Shannon, William H. Spencer, William G. Stimpson, William Sword, John Thomson, Isaac White, and John H. Willmott. A few were regulars, some served infrequently.

One reason for the overpopulation of JPs was patronage. A party in control of the provincial government used the “spoils of office” to reward its political friends, many being appointed justices of the peace. Premier Mowat enjoyed this exercise and used it to his continuing advantage. Naming magistrates and grand juries was, as historian Desmond Brown notes about Nova Scotia but which was as true for Ontario, “a prime source of patronage.”

Today the term patronage carries the negative connotation of paying off a party supporter with a job, but in the past this practice of hiring and appointing political supporters entailed more. Beyond the partisan benefits derived from filling positions with government loyalists, patronage was a means to maintain the established order, by ensuring the regime’s laws would be enforced and its values upheld. People in power had a point of view about the importance of this and wanted, at ground level, to ensure continuance of the conditions in which they operated.

If patronage had a defensible place in this scheme of things, a second factor contributing to a “higher than expected” number of JPs was the absence of any directing mind for the process of creating and keeping them. While the power to appoint was real, coordination was absent, control a chimera. Government was limited, and the modern public service had yet to emerge. With the government lacking an administrative system to oversee such matters, nobody had a clue how many JPs were even alive, let alone reporting for duty across Ontario.

The provincial government, unable to keep an accurate record of its uncounted JPs, threw up its hands and just kept appointing more, a loose precautionary measure to ensure that public policy and party requirements alike were being broadly served. Intermittently, Ontario’s government not only made a further wave of new appointments, but for good measure renewed all the appointed JPs believed to be in office at the time. This loose practice was of a piece with that era of approximation in record keeping. Voters’ lists, too, continued to carry names of people who had moved away or moved on.

Looking back, it is easy to believe this haphazard system might have been better. Yet, an early Muskoka justice of the peace, W.E. Foot, shows why it was hard for the attorney general’s office in Toronto to know where, across Ontario’s sprawling hinterland, all its JPs were scattered. Foot hustled to Canada from Ireland in 1872 to claim free land in Muskoka’s Medora Township, locating his property at an indentation of Lake Muskoka that he named “Foot’s Bay.” However, like many other free-grant settlers, he later moved into Bracebridge, leaving behind his original name on that lakeside locale.

In Bracebridge Mr. Foot became active as a justice of the peace, among other things, but in the early 1880s the aptly named man again took foot, shipping out this time for the Northwest Territory. There he stayed until relocating to Toronto in 1886. Then he quit the provincial capital for Parry Sound, where he became deputy registrar and justice of the peace for the next twenty years. Clearly, being a JP did not hold one down. As Foot in fact showed, it was a ticket to ride in Canada’s mobile and developing society during the country’s dynamic decades of settlement. He became part of society’s free-floating supply of JPs. His story was far from unique.

Beyond death and mobility, something else made it hard to keep an accurate central record in Toronto of who, at any given time, might be presiding in Ontario’s far-flung Magistrate’s Courts. Justices of the peace included everyone elected as mayors and reeves, plus all those appointed game wardens. By virtue of holding their office or position, they were empowered ex officio (emanating from office) to act as JPs in addition to their other duties. This component of the system not only ensured a well-grounded local element, but reinforced the local power structure, the crossover or combination of roles oddly echoing the magistrates’ earlier all-embracing role in local governance. The fact that municipal elections were held every New Year’s Day meant that across the province a reasonably frequent turnover occurred among those who held these offices. This annual change in elected officials contributed to the confusion over who was sitting as a justice of the peace. The number of game wardens was equally uncertain, for similar reasons of appointment and continuance in office.

Sometimes the only person available to hear a case was one of these ex officio municipal officials. Huntsville, twenty-five miles north of Bracebridge, was incorporated as a village in 1886, so, from that date, Huntsville’s first reeve, L.E. Kinton, could have acted as a JP, giving swifter justice and avoiding the cost and inconvenience of travel to Bracebridge. Life must have been peaceful in Huntsville’s opening days, however, because the first recorded dispute only came several years later when Dr. F.L. Howland, Kinton’s successor as reeve, presided in a makeshift courtroom. The case involved two Chaffey Township neighbours who got into a fight over a contested line fence between their properties.

The complainant, with one blackened eye swollen shut and the other side of his face puffed up, sat in court by himself, looking dejected, seeking justice for his black eye and redress for his removed fence. The defendant, a much smaller man, recounted local historian Joe Cookson, sat beside his wife, “a very hefty and capable looking woman,” “looking equally as glum.”

As a lone justice of the peace, Reeve Howland was to review the case and, if he found the complaint justified, send it for trial in Bracebridge. Howland questioned the complainant about the reason for the dispute, asked about the location of the attack, then inquired, “How many times did this man hit you?”

“Oh! He never hit me, your honour. No siree, it was her. That woman’s a regular devil, your honour. She’s a menace to the countryside.”

“You’re sure the defendant himself never struck you?”

“Quite sure, your honour. He’s a kindly sort of man. But her, I sure could tell you plenty.”

“Never mind,” coughed Dr. Howland, as he cleared his throat, looked down, and shuffled some papers on his desk. He then looked up again to pronounce: “I’m going to dismiss this case and bind all three of you over to keep the peace. In regards to the fence, next time I see the reeve of Chaffey I’ll get him to send his ‘fence viewers’ over to look the situation over. We’ll abide by their decision. Case dismissed.”

Whether as a medical man, or head of a council, or the newspaper editor he also was, Dr. Howland as an ex officio justice of the peace had clearly acquired practical ways to resolve contentious matters.

A small town’s watchful eyes and active tongues usually meant that culprits and perpetrators were promptly arraigned.

One day some men were brought up for tossing attention-getting candies at girls during a Salvation Army church service. Then next, a sly trapper appeared after getting caught with 176 muskrat pelts out of season. Plenty of heavier action was served up, too: men fighting in the woods with axes, men fighting along the roads with shovels and buggy whips, a husband threatening to slit his wife’s throat from ear to ear with his straight razor.

A constant flow of assault and battery cases moved through Magistrate’s Court in 1890s Bracebridge, too, as men settled scores and the town danced to its steady rhythm of street brawls.

The slosh of alcohol showed up everywhere, from harmless drunks sitting in the street to instruct enthralled school children, to spiteful ones slipping insinuations about a man’s wife into barroom talk and provoking a bare-knuckled, knockdown fistfight. Life was raw in many ways. Shooting a neighbour’s dog did not go unpunished. Those who destroyed other men’s fences, whether through burning, stealing, or vandalizing, were brought to justice.

The town was a theatre that never closed, and the justice of the peace was always standing by, ready to perform his leading role with the ever-shifting cast of characters.

A variety of conflicts to be adjudicated were spawned by disagreements over money and commerce, such as financial struggles over unpaid wages and broken contracts. Logs, because they were valuable, were often the object of money-based conflicts, as men struggled to acquire these assets through illegal cutting, outright theft, bushlot battles over the location of property lines and the logs within them, and skirmishes over unmarked logs allegedly found in the public domain along the roadside.

Captains charged for operating boats without a licence for commercial purposes, for transporting more paying passengers across Muskoka’s lakes than their boats were authorized to carry, or for selling fresh garden produce to summer cottagers (including a judge) at the end of their docks without being licensed to do so, presented another face of Muskoka’s ongoing conflicts: local officials sought to regulate commerce by challenging enterprising individuals who, for their part, helpfully sought to provide important services in a district dependant on tourism. It was a defining conflict for “the rule of law.”

Joining this steady parade of criminal and financial cases, another procession through the Magistrate’s Courtroom emanated from the community’s social and cultural impulses. On this stage the magistrate’s performance was to enforce laws that satisfied community norms when lack of respect, absence of courtesy, cutting corners, dodging blame, creating mischief, making mistakes, expressing rude resentments, or indulging in escapades went beyond accepted standards of propriety. In this, James Boyer had to contend with the double standards of humans who celebrate virtue but look to find it in others more than in themselves.

Brothels, whether operating in town or at a discreet buggy ride’s distance into the countryside, generated courtroom sensations, and in doing so, epitomized the conflicts created by the community’s double standard. Less serious but in like vein was a honeymoon charivari in Bracebridge that amused many townsfolk who chuckled to think that the groom was not the only young man to have fun on his wedding night, but which predictably offended a few. The event became a cause of mild consternation after its youthful perpetrators were dragged by the town’s stern chief constable, “Old Man Dodd,” before a bemused magistrate as the community sought to find its markers for moral probity.

Other cases, whether arising from misbehaviour at church meetings and theatrical performances, or other unmannerly outbreaks, seem petty by almost any standard. Yet, they do serve to underscore how some law or other against public mischief is always handy and awaiting invocation by public authorities wanting to constrain unruly or high-spirited humans.

Whether a case was grave or trivial, the Bracebridge Magistrate’s Court in the 1890s generally served as a fast, convenient, and reliable arena of justice.

A prosecution begun on March 11, 1895, by Chief Constable Robert Armstrong against Elizabeth Weston for running a brothel was adjourned by Justice of the Peace Boyer so the chief could procure evidence, and when court resumed just two days later, the charge against her was “dismissed for want of evidence.” Constable Armstrong, having learned his lesson in court, subsequently stepped forward much better prepared to bring charges against “Queenie” Dufresne, calling a parade of witnesses who described the late-night comings and goings at her house of ill-fame, and got her convicted.

Muskoka Magistrate’s Court was the ever-ready venue to resolve conflicts between private parties and to enforce public laws. The former included fighting spouses, employees suing for unpaid wages, and owners seeking the recovery of stolen dogs and chickens. The latter ranged from municipal bylaw infractions detected by the town constable or the local hygiene inspector, to breaches of the statutes of the Province of Ontario and the Dominion of Canada dealing with licensing of vessels, prostitution, firearms, hunting, trapping, fishing, distilling liquor, and gambling.

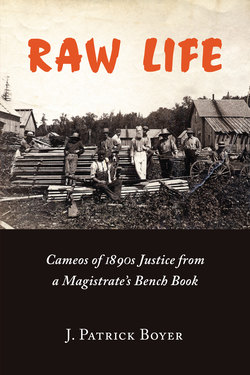

The court was generally convened in the town hall on Dominion Street in Bracebridge. Prominent in the centre of the community, it sat adjacent to the Muskoka Herald building, whose stone-walled basement was rented out as a convenient lock-up for accused persons awaiting their appearance in court until the number of attempted breakouts did such damage to the structure that the newspaper proprietors cancelled the arrangement.

Bracebridge Town Hall on Dominion Street, where James Boyer was municipal clerk, also conveniently housed Magistrate’s Court, over which he presided. The Muskoka Herald building is to the left; its cellar was used as the town jail for a period until many attempted breakouts by prisoners did such damage the arrangement was cancelled.

Depending on the number of people attending court, sessions took place either in the council chamber, or the larger second-floor entertainment hall, a proscenium theatre otherwise alive with community plays, touring concerts, or library-sponsored readings by such popular visiting notables as First Nations poet Pauline Johnson. Although such arrangements may seem slightly improvised, they were formality itself compared to the series of makeshift courtrooms used by the Muskoka magistrate in the Orange Lodge hall and elsewhere around town prior to erection of the capacious town hall in 1881.

The tall, redbrick Bracebridge municipal hall was not only the most prominent building on the most prestigious street in town, but was also a highly convenient venue for James Boyer, because he could fulfill his duties as justice of the peace, attend to his functions as municipal clerk, conduct his conveyancing practice, and receive calligraphy orders for memorial addresses, all within the same precincts, or just next door at the adjacent Land Registry Office. Such convenience facilitated speedy justice, because court could be immediately convened whenever the need arose.

The adage “justice delayed is justice denied” was taken to heart. Justice of the Peace James Boyer was never off duty. His court was a continuously open stage for ready justice. He heard cases on Saturday. If it was after hours, aggrieved parties went to his modest wood-frame residence at the north end of the town’s main street. If he was home ill, as he once was when the town constable brought in boys he’d caught stealing chickens, James rose from his sick bed and dealt with such urgent matters anyway. Even on Christmas Day, justice in Bracebridge did not rest: he opened his door to deal with a constable who’d brought in a couple men intoxicated from celebrating the Christ child’s birth. For nighttime emergencies, he could reliably be reached at his home. If he was out of town on municipal business, it was “next man up”; the town had other JPs who could fill the breach.

In good weather the JPs sometimes were disposed to “balance the convenience of the parties” by taking themselves to other locales in Muskoka. Thus, James Boyer and John McDermott went to Port Carling to hear a case in mid-August 1897, a time of year when the inescapable necessity of a scenic boat trip down the river from Bracebridge and up Lake Muskoka to picturesque Port Carling happily served the ends of justice, although apparently no occasion presented itself requiring them to travel to Port Carling by sleigh in January. Another time, the court was held in the village of Uffington. These travelling courts were rare.

Magistrate’s Court in Bracebridge was, of course, just one stage in a larger theatre for the administration of justice. At the same time that James Boyer was presiding in it, higher courts were offering Muskokans more enthralling lessons about the harsher climes of civil litigation and criminal law.

One of the most dramatic civil cases arose from the burning of steamboat Flora Barnes. The “Flora Barnes trouble” began in 1883, when Bracebridge was still a village and James Boyer was already conducting Magistrate’s Court, but a decade before his cases reported in this book took place.

The Flora Barnes had been tied up for some time at the town wharf below the falls in Bracebridge Bay. Under instruction from town council to follow a strict line in collecting taxes, particularly for non-residents of the municipality, the town constable seized the steamer and offered her for sale to cover the owner’s unpaid taxes. The worst thing that could have happened then did: destruction of the craft by fire.

Following the fire, the ship’s owner, Thomas Barnes, filed suit claiming some $3,500 in damages from the village, alleging illegal seizure. On March 20, 1883, Bracebridge clerk James Boyer brought before council the fateful letter from Barnes’s Toronto lawyers, Malone & Malone, advising of the claim. In response, village council retained the services of a Barrie firm, Lount & Lount. When the case first came before the Barrie assizes it was adjourned. The day of reckoning would be postponed for as long as Samuel and George Lount could use legal delaying tactics.

A year and one week passed before the case came up again for hearing, on March 27, 1884. The trial at Barrie was a disaster for the village. The expense of providing witnesses mounted, as a parade of those giving evidence made their way to the stand day after day. In total, there were more than a dozen men (including James Boyer), a combination of Bracebridge officials or men with particular knowledge of the matter, as well as experts retained by the Lount firm. All this evidence, and the cost to adduce it, was to no avail. The village of Bracebridge was ordered to pay Thomas Barnes his claim for damages, and costs as well.

Still in a state of shock, Bracebridge councillors met in June, almost instinctively deciding not to let the matter rest. The village’s appeal would be taken by a different Barrie firm, Strathy & Ault. A month later, council met again to consider a letter received from the new barristers about Bracebridge’s dim prospects in the matter. Reeve Alfred Hunt was instructed by council to go to Barrie and consult with Strathy and Ault. The upshot was that on August 12, the village council solemnly decided to withdraw its appeal, pay Barnes $3,671, and relinquish its claim for $310 in unpaid taxes, with the village given ninety days to raise the money.

A bylaw was prepared by Clerk Boyer, approved by council, and submitted to Bracebridge ratepayers in a plebiscite that he conducted. A reluctant citizenry voted its approval to raise four thousand dollars by debenture to liquidate the debt to Barnes. A sum of six hundred dollars was paid, as well, to Lount & Lount for their services at trial.

The major setback cast a pale of doubt over the villagers and injury to their councillors’ confidence that endured well into the 1890s. The heavy financial burden weighed on the community for years as people’s taxes paid down the four thousand dollar debenture and its stubbornly accruing interest. It would be decades in Bracebridge before any mother again named her newborn daughter Flora.

The 1890s’ most memorable criminal case involved the charge that William J. Hammond had murdered his wife. After Hammond met a girl named Katie Tough in Gravenhurst, he married her across the U.S. border in Buffalo, then placed an insurance policy on her life. When she was found dead in a snowbank back in Gravenhurst, the coroner deduced she had been poisoned. Hammond’s trial opened at Muskoka court of assizes on February 15, 1897. After hearing the evidence, however, the jury in Bracebridge disagreed with the coroner’s conclusion. Seven voted for acquittal, five for conviction. With a hung jury, a new trial was ordered.

At the fall assizes that year, a different jury returned a verdict of guilty. Hammond’s death sentence was set for February 18, 1898, but with an appeal pending, the case continued to excite wide interest across Muskoka and in Toronto’s daily newspapers. A month before his pending execution, the Muskoka Herald ran the following, penned though not signed by James Boyer: “Upon the decision of the Chancery Divisional Court in regards to two points of law hangs the life of William J. Hammond, who is now in the condemned cell in the Bracebridge jail awaiting his doom on February 18th. A jury of his peers disagreed at his first trial, but when the case was heard a second time a verdict of guilty was returned and he was sentenced to the gallows. The crime was committed, according to the Crown, so that Hammond could profit by the insurance policies placed upon the life of his wife.”

With the clock running down toward his execution, the Court of Appeal decided the evidence given by Hammond at the inquest after his wife’s death should not have been allowed at the second trial. So another new trial was ordered. Hammond’s third trial for the same crime opened at the Muskoka assizes on June 2, 1898. The case had now become so notorious that Ontario’s chief justice, Sir William R. Meredith, a former leader of the Ontario Conservative Party in the legislature, travelled from Toronto to Bracebridge in Muskoka’s pleasant early summer season to conduct the trial himself.

No new witnesses were called. Very little new evidence was introduced, and that which was adduced was found immaterial. The essential story remained the same. Katie had been found in the snow in Gravenhurst March 6, 1896, in a dying condition said to be caused by swallowing poison. Constable Archie Sloan investigated and told of prussic acid purchases in Gravenhurst the same day. The jury retired for an hour and evidently found the chain of evidence about as strong and complete as circumstantial evidence could make a case. They returned to the courtroom, bringing in a verdict of guilty.

Chief Justice Meredith, seizing the opportunity, delivered a tongue-lashing to William Hammond while sending a moral message to the general public. In pronouncing, yet again, the sentence of death on Hammond, Meredith stated: “For your poor and aged father there is profound sympathy: had you been as faithful to your wife as he has been to you, the death and misery you have caused would not have taken place and you would not be standing where you are, a convicted murderer.”

Because Bracebridge’s jail was notorious for the ease prisoners had in escaping it, Hammond was imprisoned in the Simcoe County Gaol at Barrie until September 8, when he was delivered back to Bracebridge, securely shackled. Ontario’s official executioner came to town as well, and began building a scaffold in the yard of the Muskoka District Gaol on Dominion Street. The sound and sight of its construction attracted onlookers. Drama in the community mounted. Hammond himself could hear the sawing and hammering as his gallows took shape in the days before he was to die.

On the appointed day, as the eerie grey light of dawn broke over the staged spectacle, the town bell began to toll. Its hollow tone echoed ominously across the small community’s rooftops, the mood of solemn expectation thickening. In a further theatrical flourish, a black flag was run up the pole at the town hall, adjacent to the gallows, heightening the bleak moment’s macabre drama.

Up the fresh wooden steps to the hangman’s platform climbed young William Hammond. Townspeople had risen early to witness the spectacle as best they could through or over the walled-off jail yard. Performing their grim roles behind the whitewashed wooden fence were the sheriff, constables, a clergyman, and the hangman. The assembly looked on in stony silence. The convicted murderer was directed to stand on the hinged trap door. The coarse rope noose was secured around his neck. The door beneath his feet was released. The rope snapped taught as he plummeted down. The noose accomplished its crude purpose, ending William Hammond’s life early that September morning.

Public executions continued into the 1890s because conventional wisdom held that the value of such an exercise, to be a truly instructive lesson, demanded a strong closing scene, like a mutinous shipmate being flogged on deck or keelhauled in the forced presence of the crew. Public execution was believed to deliver an educational punch for the populace by being both enthralling and revolting. Hammond’s 1898 hanging took place behind a high wooden fence and out of direct sight for many people, but the event remained the talk of the town for years to come. Crime did not pay. The bleak finality of Hammond’s quest for cash and his execution set a mood that reached everywhere crimes were being tried and punished in Bracebridge, including Magistrate’s Court.

To the chagrin of public authorities, however, not every crime resulted in a criminal being brought to justice, rather counteracting the moral impact of Hammond’s ghoulish execution. Muskoka’s share of mysterious murders and unsolved thefts included, for instance, the infamous Bracebridge bank robbery of 1897.

Begun in the early 1880s, Alfred Hunt’s private bank in Bracebridge, prominent in a redbrick building on the main street of town, was the very first bank to operate in Muskoka. It provided excellent service and valued convenience to its customers, who no longer had to bank at distant centres. On Thursday morning, May 27, bank clerk T.H. Pringle arrived at his usual hour to open up, only to be greeted by the strong odour of gunpowder. He was astounded to discover the building had been entered during the night. Making his way directly to the vault, he found a hole had been drilled through the door and the combination lock blown off.

As the twentieth century arrived, Muskoka District’s prestigious new Court House opened at the corner of Dominion and Ontario streets in Bracebridge, just as James Boyer retired after a quarter-century as district magistrate. His successors would hold court here.

Across town, Thomas Magee, who had earlier reported to police several tools missing from his blacksmithy and wagon shop, soon learned that his brace, sledgehammer, and crowbar were now at Hunt’s Bank, being held as exhibits for a trial if a culprit could be apprehended. Although his tools were in the bank, gone missing from it were some one thousand dollars in cash, several gold watches, some notes of exchange, Mickle Lumber Company orders, and nine thousand dollars in the town’s most recent waterworks debentures, issued to Richard Lance of Beatrice, who had left them with Mr. Hunt for safekeeping. Magee got his tools back, in time, but no one was ever brought to justice for this well-planned robbery. The lesson from that one, to those who sought to believe it, was that crime did pay

Within the year the Hunt Bank closed. Its crash shook Bracebridge and the large surrounding area of Muskoka. The bank’s collapse wiped out Alfred Hunt’s own extensive fortune, but the depositors at his bank received the return of nearly all their money. Hunt, whom townspeople had earlier elected mayor in the mid-1890s, continued to be held in high local esteem. “The bank should not have busted,” asserted the bank’s solicitor, Arthur A. Mahaffy, who believed the Hunt Bank to still be fundamentally sound. But Alfred Hunt, focused on the bank’s sizeable problems rather than its basic soundness, and still shaken by the bank robbery the year before, persisted in assigning his assets for the benefit of the bank’s creditors. That was the end of independent local banking in Muskoka. The national banks promptly moved in.

These three cases and many other higher court proceedings in Bracebridge added to the local judicial culture of the 1890s, theatre that was rounded out by the all-too-human vignettes unfolding, at the same time, on the stage of Magistrate’s Court.