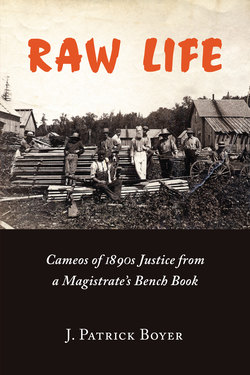

Читать книгу Raw Life - J. Patrick Boyer - Страница 14

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеThe Punishments: Common Gaol, Fines, and Social Ignominy

A wide variety of outcomes were possible in Magistrate’s Court.

Occasionally, charges were dismissed. This happened when there was a lack of sufficient evidence to convict the madam running a Bracebridge brothel, or when a township council prosecuted a hapless farmer for unlicensed selling of his vegetables by boat to summer cottagers at their docks and breaching an anti-hawking bylaw council had only enacted a few days earlier. Sometimes an untrained police constable or overly zealous prosecutor brought cases before James Boyer that seemed to be in the nuisance category. Some cases were excessively trivial. As a justice of the peace, he needed to be discerning and compassionate in dismissing them.

But most often the charges stuck. Typically, a guilty party was ordered to pay a fine. Some had to post a bond or surety. On rare occasions, even though the accused was found guilty, the punishment was suspended. When the case demanded it, the nearby Bracebridge lock-up was a major part of the magistrate’s arsenal of punishments. A number of those convicted served time in jail as an immediate sentence, or as a result of being unable to pay their fine.

The days when a thief or arsonist could be sentenced to suffer social humiliation, and perhaps physical injury, in public stocks, were gone. With his head, hands, and feet protruding through imprisoning boards, locals could formerly insult and harass the exposed convict at will. In this way the culprit’s punishment was made palpable by citizens of the community ventilating their rage and mockery — a midpoint in the transition from mob rule to the rule of law. Even though stocks were never in use on the Bracebridge commons, there were a number of other ways private citizens still performed an activist role in the justice system, for instance arraigning individuals they caught breaking a law and collecting half the fine as a reward. Nor was use of public shaming as punishment entirely foreign to Bracebridge Magistrate’s Court in the 1890s; convicted prostitutes were ordered to either serve time with hard labour or get out of town.

In relative terms, some of the 1890s jail sentences that Bracebridge justices of the peace imposed seem as draconian by today’s standards as public execution was for murder: weeks in the lock-up for seemingly minor transgressions.

Those at the lower edge of Muskoka society often paid their fines not with money but with their time, because in sentencing, jail time was always a backup, the stipulated default punishment for those unable to pay cash. For a number of the poor, going behind bars was the only option.

Some stiff sentences seem outrageously unfair: weeks or months in detention for simple vagrancy. But could these sentences have been charitable acts? As the days shortened and temperatures fell, Bracebridge constables found derelict men and brought them to the justice of the peace. James Boyer, hearing evidence that their crime was having no visible means of support nor any place to go, ordered them to a period of incarceration long enough to carry them through the harshest of the winter months in sheltered and dry quarters with adequate food.

In the 1890s common vagrancy was an offence under Canada’s Criminal Code, partly to protect communities, partly to protect vagrants. No welfare programs existed to support the indigent. This expedient of putting homeless, unemployed poor people in the local lock-up improvised a primitive charity. Local police and magistrates preferred that those with no means of support not freeze or starve to death during winter in the streets or abandoned sheds of their community. In Bracebridge, in such cases, the jail door was seldom locked on these inmates.

If time in jail was possibly a blessing for the homeless man sentenced to food and shelter for the winter, it was definitely a setback for the prostitute removed from society and unable to earn her money. The same punishment did not fit everyone equally.

Across Canada jails were as different as the places in which they stood. Some were adequate but others not, most showing in common simply that those who built them wanted to create rudimentary facilities for the least amount of money. With limited funds for schools and none for a hospital, Bracebridge council’s impulse to frugality blended with a common belief that criminals needed nothing more than the bare minimum. Jail was a place where they were placed to be kept away from society, on a par with the bleak asylums with barred windows and locked doors where “crazy people” were incarcerated.

The first Bracebridge jail was built of logs. It sat in the centre of the settlement, at the corner of Dominion and Ontario streets. Like most early structures in the community, the jail featured natural elements, from its sturdy log walls right down to its bare dirt floor. No sooner had the facility been built, in anticipation of crime to come, than a collection was taken up to pay bail for its first occupant. Enthusiastic locals chipped in a total of twenty-five dollars. This relatively large amount was then held in trust for the benefit of the lock-up’s first customer. It was a whimsical Bracebridge concept for celebrating the jail’s inauguration with its prisoner’s immediate release, an inventive equivalent to an official opening ceremony for the new facility.

This log jail still exists today. It is not a heritage attraction for a town dependent on tourism, as one might expect, but a storage building at a private home along Santa’s Village Road on the west side of town. Its ancient log walls are now covered with board-and-batten. Geraniums in planters decorate its exterior to complete the disguise.

The first Bracebridge jail, shown as it exists today — its log walls covered with siding, decorated with flowers, serving as a storage shed.

The structure was hauled to this location more than a century ago from its original site, to make way for a large, wooden, provincial government office building. That, in turn, gave way in 1900 to Muskoka’s red-brick district courthouse on the same location.

As life in town became testier and occupants in the jail more frequent, feeding the inmates became an item of business. Robert White, who operated a grocery store and bakery in a block of brick buildings at the corner of Manitoba and Mary streets where St. Thomas’s Anglican Church stands today, bid on and won the contract to be “keeper of the gaol,” which primarily meant providing prisoners their food.

White sometimes sent his young employee, Gerard Simmons, with these meals. On one occasion Simmons took the tray of food to two inmates, finding the door locked and the windows secure but the prisoners gone. “Just as he was turning away to take the food back,” recounted local historian and magistrate Redmond Thomas of this episode, “he heard loud yells of ‘Wait! Wait!’ and saw two men run from the British Lion Hotel which was just across the street.”

The day before, this same pair, workers building the railroad through town, had received their pay “and in the evening had invested freely in alcoholic beverages and become so riotously drunk that they had been run in.” The next morning in the jail they “had an awful thirst and still some cash left. Right across the street they could see an oasis, the barroom of the British Lion Hotel,” explained Thomas. “The more they gazed at the British Lion, the thirstier they got.” Their inspection revealed the prison door was strong, and the windows securely barred. “But the floor! Ah, the floor! It was only earth! If a little chipmunk can dig a hole in the earth surely two husky men could dig one, too. They burrowed out of the jail and adjourned to the British Lion to slake their thirst.”

Yet, as Thomas also noted, “hard-working construction men need food too. Why buy a meal at a hotel when the public purse furnishes one for free at the jail? Why, indeed!” So, as the escapees monitored the time they should remain at large, sipping their drinks while watching through the barroom window to make sure they did not miss a free meal, they spotted young Simmons arrive, “gulped down the last of their drinks and hied themselves back to the jail for victuals!”

The inadequacy of this simple jail was on a par with other facilities forming part of the Bracebridge institutions for the administration of justice, matching for example the equally rudimentary nature of the inaugural courtroom established in Bracebridge in 1877.

Yet, the growing town was all for progress, especially when a senior level of government could pay for new facilities. Bracebridge not only needed a local lock-up, as any town might, but in addition required, as capital town of the District of Muskoka, a district jail. Because that was a responsibility of the provincial government, as part of its constitutional jurisdiction over administration of justice, the Ontario government of Premier John Sandfield Macdonald came under increasing pressure from Muskoka councils and Muskoka’s representative in the legislature, J.C. Miller, to act. In 1879 a new building housing five cells was built under a contract let by the Ontario Department of Public Works by low bidder Neil Livingstone of Gravenhurst.

This new structure was made of brick, the construction material of choice in Bracebridge after the Gibbs & Griffin brickworks had begun manufacturing locally in 1871. Solid brick walls would not only be more resistant to fire, but harder for escapees to work through than the earlier log walls and dirt floor. Erected on property reserved for the provincial government near the Land Registry Office on Dominion Street, this new lock-up inaugurated a district jail serving all Muskoka.

As part of Muskoka’s emerging facilities for the administration of justice, the jail was an improvement for incarceration of prisoners, but the district was still minimally served. A decade later, in November 1888, a grand jury in Bracebridge inspected the place and the jury’s foreman, Thomas Myers, reported to Sheriff James Whitney Bettes how “they found the gaol scrupulously clean and well aired” but recommended “a larger building, more sanitary appliances, and a safer enclosure for the yard to prevent the escape of prisoners when out for exercise.” The jurors were also concerned that the district had no provision “for insane persons awaiting the pleasure of the lieutenant governor for their removal to an institution.” In short, mentally ill persons were being kept in the jail alongside other prisoners.

James Boyer was acutely aware of the problems with the Bracebridge jail, both as magistrate and town clerk, and in 1889 helped persuade council to take the recommendations of the grand jury to heart. Council voted to send Mayor Armstrong and Councillor Hunt to Toronto as a two-man deputation authorized to discuss with Ontario’s premier the need to build a new jail for Muskoka District, the existing building “being altogether too small, insecure, and unsanitary.”

Still, another decade later, this situation had changed little. Despite recommended improvements, no further public money had been directed to these facilities. The authorities clearly knew how inadequate the district jail was, as is shown by their action in 1898 at the conclusion of the sensational murder trial of William Hammond from Gravenhurst when the prisoner was removed to Barrie for incarceration because it had a stronger jail. Hammond was securely held there, until brought back to Bracebridge for execution.

Harshness handling outsiders and misfits was an outcome of the era’s view of human character, but it was also a measure of the society’s lack of institutions and absence of procedures to cope with broken people. A bleak episode occurred during the winter of 1904, revealing a continuation of the same institutional conditions and outlooks as when the 1890s cases in this book arose. In February that year, John Eastall, an elderly man, had been sent from Huntsville to the jail in Bracebridge because he had no place to go and no one to care for him. Shortly thereafter he died. The old man, an early and respected pioneer in north Muskoka’s Sinclair Township, had been admitted

The log-cabin jail was replaced by a brick jail, which in turn was supplanted by this 1904 stone jail, which stood behind Bracebridge Town Hall, a half-block from the new District Court House. Six decades later it was torn down to put up a parking lot.

to hospital in Huntsville when his neighbours found him with hands and feet frozen. At the hospital, he was found to be mentally unstable and could not be kept there. Without facilities to keep him, lamented the Huntsville Forester, the old man “was placed in the hands of police, carried off to Bracebridge jail, suffered premature death within its dingy walls and buried, we suppose, with all the honours which belong to an old, friendless vagrant.”

The Huntsville newspaper focused its dismay on Bracebridge and its jail facilities, not its own hometown hospital and medical staff who had washed their hands of responsibility for the local man with a convenient diagnosis of mental instability and sent him away to another municipality and its rudimentary facilities. Still, even given that fact, it was true that the jail in which John Eastall died did not meet expectations. Bracebridge, after all, was not just a neighbouring municipality; it was the capital town of Muskoka, and, as such, had, or might be expected to have, public facilities commensurate with its role.

Whether in Huntsville, Bracebridge, or elsewhere across Muskoka District, the absence of adequate facilities made a mockery of the rule of law, and rendered hollow even the minimal sense of compassion in that day. Muskoka historian Susan Pryke relates how cases like John Eastall’s “haunted” Huntsville’s police chief, William Selkirk, causing him to recommend in March 1906 that town council petition the legislature to build a house of refuge. Muskoka’s member of the legislature, A.A. Mahaffy, became champion of the cause, calling a meeting of reeves, mayors, and other interested parties in Bracebridge to discuss establishing a home for the aged and infirm in the district.

“It was not as easy as Mahaffy hoped,” Pryke concluded. Even by 1921 nothing had changed. That year, at the inaugural banquet of the Muskoka Municipal Association, Mahaffy again urged Muskoka’s elected representatives to secure a house of refuge. But no home for the aged would be built in Muskoka for almost a half-century more, when one of Mahaffy’s successors as MPP for Muskoka, Robert J. Boyer, a grandson of James Boyer, spearheaded the creation of The Pines Home for the Aged in the early 1960s, facing defiant opposition from two township councils. Muskoka was last of all Ontario’s counties and districts to have such a facility. For a very long time, tough love and self-reliance endured as Muskoka’s way, the remorseless culture of people who had themselves struggled in harsh settings to make their own way.

Spending money on convicts and “lunatics” was seen as unnecessary, and referring to people who might occupy such facilities in derogatory terms seemed to make it easier to discount the need. Even after Muskoka’s imposing new district courthouse opened for business on Bracebridge’s prestigious Dominion Street in 1900, improvement of jail facilities still languished on the public agenda. Instead, the government simply leased the conveniently close stone-walled basement of the Muskoka Herald Building on Dominion Street from the newspaper’s proprietor, Edgar Bastedo, for use as a lock-up. The building, though constructed only for a newspaper and printing operation, was at least considered more secure than the earlier jail. Yet repeated damage to the newspaper’s premises by prisoners trying to break out, as earlier noted, led Bastedo to end the arrangement. Helping the community in its time of need had been instinctive for public-minded Bastedo, but his building was suffering physical damage and the reputation of the premises as a place co-occupied by feisty criminals was not helping Herald business.

This turn of events propelled Bracebridge council to get a better local lock-up. It secured a patch of land for sixty dollars from S.H. Armstrong at the rear of the town hall, where in 1904 local contractor John Baker constructed a more secure facility. It was massively built, with thick walls of stone, a sturdy door with heavy hinges and a strong lock, three cells inside, plus a stove, toilet, and small washbasin. Its few small windows, on the south side, were closely barred.

The town’s constables used these cells to detain individuals charged with an offence until they could appear before the magistrate the next morning, to house prisoners convicted and sentenced to serve jail time, and to shelter vagrants and sometimes others who were mentally ill. Beside the structure stood a stable for the town’s team of horses, which stood until 1934 when trucks replaced horses and the building was demolished. In 1967 the stone jail itself was purchased by Bracebridge lawyer H.E.S. “Bert” Sugg and razed to make way for a parking lot behind his law office. Asphalt then covered over both the space where prisoners had once paced out their days and the hollyhocks beyond their windows that had grown tall and bloomed in summer.

Whatever causes people to employ euphemistic phrases for reality, it was certainly at play in Bracebridge to describe the various lock-ups over the years. At first, to some the local jail was “the Bastille,” a humorous pretense that the town’s lock-up was on a par with the infamous stone prison in Paris. In the long era of Queen Victoria’s reign, another name for the place housing criminals, charged and convicted and sentenced to be confined in the name of the Crown, was “Her Majesty’s Cottage.” After the queen’s death, and with construction in 1904 of a new jail from local-cut stone, the popular name became, more simply, the “Stone Cottage.” Once Duncan McDonald was appointed in 1909 as warden of the district jail in Bracebridge, that centre for incarceration would become known by yet another euphemism, “Dunc’s Castle.” Adding humour or using euphemisms may have assisted to diminish reality in the minds of some.

Prisoners in Bracebridge were not always behind bars. Sometimes they were outside working, sometimes they simply escaped, and occasionally they were brought out for execution.

The new district jail was to the north of the courthouse, built at the corner of Dominion and Ontario streets in 1900. Behind the courthouse the land sloped away and a vegetable garden was created to help supply food for prisoners. Prisoners themselves tended the garden. They did more, too, recalled Magistrate Redmond Thomas, as part of their sentence of hard labour, “mowing the lawn and shovelling the snow and doing all the janitor work.”

The record of Bracebridge jails serving their intended purpose of retaining prisoners in confinement was not outstanding. One of the reasons for this poor record was the inventive determination of the prisoners, of course, but one also has to wonder about the implicit complicity of Bracebridgites themselves. The villagers had created a fund to pay the bail of the first prisoner, the authorities had dragged their feet in upgrading facilities, and if a prisoner escaped, the townsfolk would not have to pay for his food. It can be safely said that secure incarceration was never a big deal locally.