Читать книгу New Harmony, Indiana - Jane Blaffer Owen - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

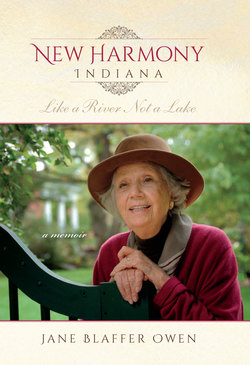

ОглавлениеJane Blaffer Owen

May 1, 2010

Fiftieth Golden Anniversary Rededication

of the Roofless Church

The first half of life is biography,

where we allow our story to be written for us by others. . . .

The second half of life must be autobiography,

authored by the Self.

J. Pittman McGehee and Damon J. Thomas,

The Invisible Church: Finding Spirituality Where You Are

IN CONTRAST TO THE WAY in which most of us in the modern world live our lives, early Celtic artisans represented the commingling of their yesterdays and tomorrows in the strands that form their everlasting and interlacing designs drawn in manuscripts and carved on monuments. I experience a similar commingling of time in New Harmony.

Extraordinary men and women brought their visions, scientific minds, talents, and, as with Robert Owen and William Maclure, their personal fortunes to New Harmony in 1826. Their likenesses adorn spaces in the national art galleries of England, Scotland, and Wales, the M. and M. Karolik Collection of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and Washington’s Smithsonian Institution. In New Harmony, their portraits hang in the Working Men’s Institute and inside the historical houses that my husband, Kenneth Dale Owen, restored. Numerous biographies document their achievements and limitations.

Readers of history, however, shall not learn from these books, portraits, or bronze effigies the extent to which the undying dead of New Harmony have directed the course of my life and impacted the lives of fellow residents, some of them close friends and allies for over half a century. Today’s visitors, whatever their reasons for coming to New Harmony, enter a community of energetic and caring citizens who, consciously or not, inhabit the past, present, and future.

The powerful river that partly encircles this town of less than nine hundred people offers another metaphor for the conjoined seasons of our lives and for my personal approach to New Harmony’s rich and varied legacies. Whether the current of its journey south is languid or swift, whether its surface darkens with filtered mud or mirrors a sky flushed with rose and lavender, the Wabash flows onward, totally alive—like the town of New Harmony itself—reminding us it is an unpredictable river, not a placid, circumscribed lake. However threatening on some days or safe and picturesque on others, this river challenged me, forcefully and fatefully, from my first arrival in New Harmony in 1941. (See the area map on the front endpaper.)

While the Wabash has provided a title for my tale of New Harmony, it does not explain why I have chosen to bind these pages with five bands of different colors, placed vertically, not horizontally. These colors and their alignment represent a philosophy bred into me by my parents and nourished by the people who, after them, have influenced and enlightened me. I owe a few words of gratitude to the remarkable man who inspired the black, red, white, yellow, and brown bands of color. But first, the genesis of our friendship.

Sometime in the early 1960s, I was invited to join an organization founded by men I admire: the theologian Paul Tillich, the psychologist Rollo May, the mythologist Joseph Campbell, the Harvard biblical scholar Amos N. Wilder, and many others, each of whom was a seminal figure in his field of study.1 The organization was formally named the Society for the Arts, Religion, and Contemporary Culture, but members and fellows always spoke of it by the initials A.R.C., as though to call attention to what the founders of the society took to be an indivisible trinity of three abiding realities—art, religion, and culture.

At an ARC annual conference, I had the good fortune to meet Frederick Franck. Born in Holland of agnostic parents, he stepped upon the world stage when he joined the medical staff of Albert Schweitzer’s famous Lambaréné clinic as an oral surgeon. Franck brought pencils, paintbrushes, and an unerring eye with him to Africa. He chronicled the sojourns and experiences of a long, creative life in his books and freestanding artworks around the world. Frederick designed Saint Francis and the Birds, a Corten steel sculpture, to place beside small Swan Lake behind the New Harmony Inn in 2004 (see numbers 1, 2, and 3 on the town map on the back endpaper). Guests and residents should smile to learn that our version contains one dove more than Franck’s similar statue in Assisi, birthplace of the patron of animals. St. Francis was an anointed prince of peace, not merely an image suitable for decorating birdbaths and feeders.

Frederick Franck’s Saint Francis and the Birds beside Swan Lake with Stephen De Staebler’s Chapel of the Little Portion in the distance.

Photograph by Janet Lorence, 2013. Saint Francis and the Birds © 2004 Frederick Franck. Courtesy the Estate of Frederick Franck and Pacem in Terris.

Franck is best remembered for Pacem in Terris, a place for people of different faiths who share a common devotion to art, music, and drama.2 I have attended plays, “transreligious” services, and concerts in this triangular enclosure, built on the stone foundation of an old mill. When Frederick and his indomitable wife Claske found and bought the remains of the mill in Warwick, New York, its interior space was a repository for neighborhood garbage. Water no longer turned the wheel that had once ground grain into flour. The once-beautiful face of the mill was disfigured, like the face of the leper whom St. Francis kissed at the beginning of his ministry a thousand years ago. A burning passion for healing turned the heart-wheels of selfless volunteers as they carted truckloads of kitchen and backyard detritus from the stone perimeter and created a stage and terraced seats within new walls. For forty years, the Francks brought music and drama to the stage of this chapel-theater. Frederick died on June 5, 2006, but his son, Lukas, Claske, and colleagues continue the work of Pacem in Terris.3

I relate this brief history of Pacem in Terris because it embodies my belief that preservation, be it of buildings or values, is better served by sustained commitment from local people than by philanthropists alone, however welcome they have been and always will be.

The chapters that follow honor other passionate preservers: Robert Owen, whose New Lanark Mills were a shining exception during the bleak reality of the Industrial Revolution; George MacLeod, who resurrected Iona; and, lastly, the men and women who have labored with me to preserve New Harmony. But before introducing these latter-day “Franciscans,” the refrain of this book’s song requires that I trace the stripes of color on its cover to their origin.

For too many years, the thriving Port of Houston lacked an adequate welcoming center for seamen on leave from their ships. A few valiant chaplains from Catholic and Protestant churches offered shelter and hospitality from a corrugated tin shack in a dangerous, poorly policed area near the port. Seamen were robbed, mugged, and sometimes killed. I was among a group of Houstonians, including Jack Brannen, MD, Howard Tellepsen Sr., and David Red, who found this sin of omission in a prosperous city scandalous. In 1968, we were joined by Jack Turner, of the Port Authority, who donated seven cyclone-fenced acres near the Ship Channel. The area was transformed into a baseball diamond, a soccer field, basketball and volleyball courts, an Olympic-size swimming pool, tracks for runners, and a pavilion. Generous citizens and foundations contributed funds for a substantial multipurpose building; members of Houston’s garden clubs provided landscaping.

The addition of a small chapel that would not emphasize one denomination over another became my responsibility. I sought the ingenuity of Frederick Franck. His response to my SOS was immediate but cautious. He would meet with the chaplains and the center’s board of directors—if they were willing to open their minds to new ideas. My faith in my mentor’s powers of persuasion was not misplaced. Though reluctant at first, the governing bodies obeyed his request for the hatch of a beached fishing boat, from which he fashioned an altar.

Frederick asked the wives of the chaplains and me to embroider leaves on the bare limbs of a large tree he had sketched on a rectangle of burlap. His proviso, however, was that we use black, red, white, yellow, and brown thread, not green. Each color was to be a welcoming beacon, inviting sailors from around the world, regardless of their nation or race, to the chapel. This hand-sewn, rough-hewn tapestry hangs above the sea-washed altar. He also duplicated a tubular banner, representing the colors and interdependence of humanity, like one at Pacem in Terris, which I hope shall fly not only over the Houston International Seafarers’ Center but, one day, over every human habitation.4

In view of my enthusiasm for the humble materials that Franck selected for the chapel, the reader may well wonder why I chose costly art for the altar of the church I envisioned for New Harmony. Some may well ask why I was so bent on providing an altar in the first place. Reasonable or not, wise or profligate, I herewith submit the stimuli that ignited my endeavors in New Harmony sixty-nine years ago.

The Roofless Church with its altar and ceremonial gate in 1962.

Photograph by James K. Mellow. Courtesy of James K. Mellow.