Читать книгу New Harmony, Indiana - Jane Blaffer Owen - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Hisorical Note

ОглавлениеConnie A. Weinzapfel

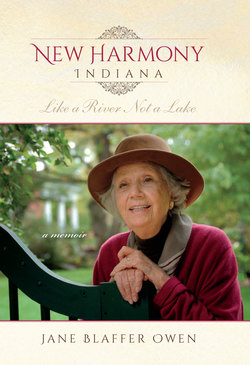

JANE BLAFFER OWEN’s memoir begins with her 1941 entry into New Harmony, Indiana, a town with a substantial and significant history. A brief overview of its history and development will provide a helpful orientation to her many references to its past.

New Harmony is the site of two of America’s important early communal experiments. The first utopians—the Harmonie Society of Iptingen, Germany, from within the area of Württemberg—were led by Georg Johann Rapp (1757–1847) from their first settlement to the Northwest Territory in 1814. (Members of the Harmonie Society have been referred to as Rappites or Harmonists.) “Father Rapp,” the title given him by his Pietist flock, and his adopted son Frederick hired engineers from Vincennes, Indiana, to design their new town, Harmonie. Streets were laid out in a perfect grid and were named for their utilitarian purposes—Church, Granary, Steammill, and Brewery, as well as East, West, North, and South streets (see the town map). The Harmonists efficiently constructed their single-family houses in a process we would today call prefabrication, as pieces were cut and numbered off-site at their mill and assembled on each town lot. Gardens for vegetables, herbs, and flowers were incorporated into the plan, and two thousand acres immediately surrounding the town were used for the Harmonists’ agricultural endeavors and formed the basis for their substantial commercial success. In keeping with their providential path as God’s chosen people, the Harmonie Society placed New Harmony for sale in 1824 in order to relocate to western Pennsylvania. Considering New Harmony’s remote location on the frontier, the Harmonists’ dwellings and public buildings were quite remarkable. The American Planning Association recognized their exemplary community design in 1998 when it designated New Harmony as a National Planning Landmark.

During the years of the Harmonie Society’s ventures in America, a parallel utopian movement was taking shape in Europe and Great Britain. In New Lanark, Scotland, Robert Owen (1771–1858) was instituting systems for the improvement of the lives of his cotton mill workers. In response to the degradations to laborers brought on by the Industrial Revolution, Owen promulgated theories that promoted education as the great equalizer for the inequities of social classes. This included planned housing and schools for all of his New Lanark employees. Owen also created an Institute for the Formation of Character in New Lanark, which, in essence, was a community education center.

Owen tried unsuccessfully for years to influence the British Parliament to enact social reforms. Likewise, he was rebuffed by other industrialists, who saw in Owen’s plans only depletion of profits. When word came that the Harmonists had placed for sale their town in the wilderness of Indiana, Owen became interested; he was already acquainted with the community, for he had corresponded with the Rapps since 1818. In 1825 Robert Owen spent much of his fortune to buy New Harmony.

Soon after purchasing the town of New Harmony, Robert Owen found a like-minded Scotsman, social reformer, and scientist William Maclure (1763–1840), who believed that the basis for the improvement of society was education. Maclure was a founder and president of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. While there, Robert Owen was reintroduced to the Pestalozzian educator Marie Duclos Fretageot. Under the patronage of Maclure, Fretageot headed a school and was well acquainted with the local intellectual community. Through her introduction, Owen met the group of people who would add substance and longevity to his utopian dream. Some went straightaway to New Harmony, like Dr. Gerard Troost—a geologist, mineralogist, zoologist, and chemist, and the first president of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Others waited for transport on the keelboat Philantropist with Robert Owen and William Maclure via the Ohio River to New Harmony during the winter of 1825–26.1 Not surprisingly, it was dubbed “The Boatload of Knowledge” for the many world-renowned scientists, educators, and professionals aboard, including Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, paleontologist, archaeologist, ichthyologist, and zoologist, together with three of his students; Thomas Say, entomologist, conchologist, and artist; Thomas Stedman Whitwell, an English architect who designed Owen’s quadrangular community design, a structure intended to be built just south of New Harmony where the ultimate realization of Owen’s millennial dream would take place; Dr. William Price, physician; Robert Dale Owen, eldest son of Robert Owen; the Pestalozzian educators Marie Duclos Fretageot and William S. Phiquepal, with ten students; and Lucy Sistare, artist and educator, among others.2

The Owen/Maclure community introduced educational and social reforms to America and was to be a model for other villages to be built around the world. After only two years, the envisioned community of mutual cooperation did not survive as a cohesive unit, due primarily to a lack of “mutual cooperation” among the throngs of disparate people attracted to the ideals of the utopian experiment.

Although William Maclure and Robert Owen both left the community, many of the scientists, educators, and professionals remained. Robert Owen’s sons Robert Dale, Richard, David Dale, and William, and one daughter, Jane Dale Owen Fauntleroy, provided continuity and made important contributions during New Harmony’s Post Communal Period from 1828 to 1858. New Harmony provided geological and natural science collections for the foundation of the Smithsonian Institution. Indeed, New Harmony became a national center for scientific and educational innovation until the Civil War. During these years, New Harmony was one of the most important training and research centers for the study of the natural sciences in America.

In the early 1900s, one hundred years after the Harmonists founded the town, New Harmony experienced a renewed vigor in the lives of the townspeople and the physical environment of the town, as evidenced in the photographs of William F. Lichtenberger and Homer Fauntleroy.3 Prosperity from agriculture built many fine Victorian homes among the comparatively modest Harmonist dwellings. Strong leadership and planning enabled the town to erect monumental public buildings, including the 1894 Working Men’s Institute and the 1913 Murphy Auditorium. Pride in community and recognition of the town’s historical importance enabled New Harmony to overcome losses from the 1908 Monitor Corner fire and the 1913 flood.

In early 1913, the New Harmony Town Council created a Centennial Commission, consisting of its own members, the trustees of the Working Men’s Institute, and ten citizens of the town to be appointed by the president of the Town Council, “five of whom must be women recommended by the Woman’s Library Club.” In the Program of the Centennial Celebration at New Harmony, Indiana, the opening statement to the public declares, “No town or city in the United States boasts a history of greater romantic or sociological interest.”

A great celebration marked New Harmony’s centennial in 1914, and we began our yearlong bicentennial celebrations with pealing church bells and sparklers at midnight on New Year’s Day 2014. The New Harmony Bicentennial Commission is pleased to remember the contributions of Jane Blaffer Owen posthumously as the bicentennial honoree. As Jane Owen remarked in an interview in May 2008, “The dreams of the people who have come before are finally being realized now, 200 years later.”4

Nature provided the lure for both Native Americans and the Harmonie Society to settle here. It provided subject matter for the scientists and artists of the Owen/Maclure community and created a fertile base for agriculture. The natural beauty of New Harmony continues as an attraction today. I believe that the present inhabitants will honor the endeavors and good intentions of our forebears and continue to care for our past, make the most of the moment, and work together toward the ideal.

Connie A. Weinzapfel, Director, Historic New Harmony—a unified program of the University of Southern Indiana and the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites, Inc.