Читать книгу New Harmony, Indiana - Jane Blaffer Owen - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеJohn Philip Newell

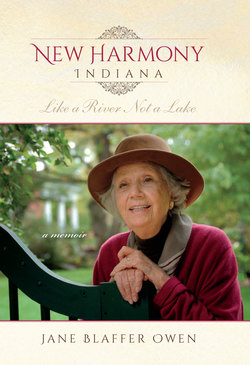

JANE BLAFFER OWEN ranks among the most beautiful and wise women the modern world has known. I met her over ten years ago. She was already in her mid-eighties. And I fell in love with her immediately, as have countless other men and women of every age and stage. Yes, she was beautiful physically as well as intellectually and emotionally. But it was the way she embodied vision that drew most of us to her. And we who love her have come from many, many disciplines, ranging from art and culture to science and religion.

Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, said that the Spirit is a coniunctio oppositorum, a conjoining of what has been considered opposite: heaven and earth, spirit and matter, the feminine and the masculine, East and West, the night and the day, the unconscious and the conscious, the head and the heart, spirituality and sexuality, our individual stories and the one story, the story of the Universe. Jane Owen lived among us as a messenger of Spirit. She was forever weaving together what has been torn apart.

Close to the heart of her vision is the Roofless Church of New Harmony. It has four defining walls but truly no roof. It is to me one of the most prophetic sites of prayer in the Western world. Over fifty years ago, well in advance of the earth-awareness of today, Jane Owen saw that our sacred sites must not be cut off from the temple of the earth. Our places of prayer must not represent separateness from the other species and the other people of the world. The Roofless Church stands as an abiding testimony to this vision. The primary context of religion, and indeed of life itself, must be the great and living cathedral of earth, sea, and sky. If we are to be whole, we must come back into relationship with Creation.

Jane Blaffer Owen with John Philip Newell.

Photograph by Alison Erazmus, 2010.

On May 1, 2010, we rededicated the Roofless Church on the fiftieth anniversary of its consecration. It was as if Jane Owen, who died the next month at the age of ninety-five, was determined to celebrate its jubilee, such was the significance of the church to her vision.1 The next day, in studying photographs of the celebration, I pointed out to her that she had been gazing around quite a bit during the procession, to which she replied, “I was just counting the number of people.” Jane Owen was forever passionate about continuing the vision.

At the heart of the Roofless Church is her most cherished work of art Descent of the Holy Spirit (Notre Dame de Liesse) by Jacques Lipchitz.2 The sculpture is of the Spirit, in the shape of a dove, descending on an abstract divine feminine form that is opening to give birth. At one level Lipchitz is pointing to the story of Jesus, who was conceived by the Spirit in the womb of Mary. But at another level Lipchitz is pointing to the story of the Universe. Everything that has being has been conceived by the Spirit in the womb of the Universe. In other words, everything is sacred. This is the vision that guided Jane Owen to commit herself to reweaving the strands of life—between nations, between cultures, between religions, between any of the so-called opposites that have tragically separated us in our lives and world.

She knew the sacredness and the beauty of life. But never did she forget the brokenness and pain of life. At the other end of the Roofless Church is another sculpture, Pietà by Stephen De Staebler. It is a primitive, naked, feminine form. In her sides and feet are the nail marks of crucifixion. And her breast is split open to reveal the head of her crucified son emerging from within her. When our child suffers or when one we love is in agony, we experience their suffering not from afar but as coming from deep within us. Jane Owen knew such suffering in her family and life. She also knew, as De Staebler’s sculpture so powerfully communicates, that if there is to be real healing in our world, we must know the brokenness of other nations, other species, other families as part of our own brokenness. Jane’s countenance was beautiful. Yet it was a countenance that showed also deep sorrow with the brokenness of the world.

One of the last things she said to me was that New Harmony saved her. Was I mishearing her? Many have said, and many will continue to say, that Jane Blaffer Owen saved New Harmony. Certainly this is part of the story. But Jane Owen was disclosing to me another truth, a more hidden part of the story. New Harmony saved her because she found in this town and in its people the object of her love. That is why she called it her “second marriage.” She knew that it was only because she faithfully gave herself in love to New Harmony that she truly found herself. Such is the way of love. It is in giving our heart to the well-being of the other that we most truly become well ourselves.

Jane Owen would often say that the great ones in our lives who have died are like “allies” on the other side of death. “And maybe,” she would say, “just maybe, they can do more for us on the other side than they did on this side.” I agree. And I believe that Jane Owen is one of these great ones. We will never again see her picking peonies to give to New Harmony residents and visitors alike. We will never again hear her laughter at table as she works her magic of bringing different people and disciplines together. We will never again receive one of her many handwritten notes suggesting the next way of serving the dream of a new harmony in our world. But we need never lose communion with her heart and her vision. For she is a great ally. And her work with us is not finished.

The Reverend Dr. John Philip Newell, Edinburgh, Scotland, is internationally acclaimed for his work in the field of Celtic spirituality as a minister and peacemaker, and the author of more than fifteen books, including A New Harmony: The Spirit, the Earth, and the Human Soul.