Читать книгу New Harmony, Indiana - Jane Blaffer Owen - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHumility, that low, sweet root,

From which all heavenly virtues shoot . . .

—Thomas Moore, The Loves of the Angels

CHAPTER 2

Indian Mound

My fears about a racing-stable absentee husband began to dissipate. In the first year of our marriage, Kenneth began necessary improvements to the Laboratory residence and purchased a large portion of Robert Owen’s original holdings, rolling farmlands that culminated in the highest point on the Wabash River for many miles, a rise known as Indian Mound (see area map). Archaeologists called it a midden, a deposit containing refuse indicative of an early human settlement; this one was created with mussel shells discarded by prehistoric Native Americans. But generations of townspeople had other names and softer feelings for this ageless place. Indian Mound became for Kenneth and me (and later our three daughters) a refuge from the rattle of trucks along Church Street, heat, and concerns. The greatest reward for climbing that far, however, was the expansive view of Cut-Off Island, belonging half to Indiana and half to the nearby fertile, flat plains of Illinois, still innocent of factories and housing developments on the other bank of the Wabash (see area map).1

Kenneth planned to grow corn and soybeans on his newly acquired Indian Mound Farm and sought expertise from members of Purdue’s agricultural department concerning how best to reinvigorate the land that had lain fallow for many years (see area map). As a young boy, he had picked corn on the gentry farm on the Old Plank Road for a dollar a day. His agricultural instincts were sound, but he needed professional advice. Fences would be built and hay sown before purebred Herefords could graze on well-seeded fields.

Heeding Louis Bromfield’s advice that the best manure is the owner’s foot tracks, we headed for the farm soon after our return to New Harmony from Houston in the late spring of 1942.2 I was several months pregnant with our first child and eager to have the unborn Owen accompany us on our excursions to Indian Mound. We passed Sled Hill, so called because it is steep enough for sledding in winter, which I’ve done by starlight (see area map). We walked beyond the dairy barn and continued through catalpa trees, which showered us with orchid-like blossoms, to reach the broad back of the hallowed mound.

The sound of whirling blades assaulted our ears. A small but deadly machine, like an armored knight, was waging war against my husband’s invasive enemies, the thorn trees that grew on land intended for pasture. The stump remover was winning the battle, and Kenneth was buoyant. Whatever hindered the best use of the land was abhorrent to him, a splinter in his flesh, for land to my husband was what it had been to the Woodland Indians, his other body. He grinned broadly, having slain his dragons for the day.

Regaining our breath after the brief climb and filling our lungs with the clover-fragrant air, he turned to me, for I had lagged behind.

“I don’t know how you feel about Indian Mound, but I know that we don’t really own it. Time does. Let’s never build here or allow a paved road to come anywhere near.”

“I love you, Kenneth, for thinking this way. We’ll let nothing rob eternity of its foothold on this place. Unless . . . ,” I added timidly.

“Unless what?” came his no-nonsense reply.

I became silent because unpredictable emotions were rising from many leagues below the level of my conscious mind, claiming my complete attention.

Abraham, patriarch of our Jewish-Christian-Muslim faith, a historical figure whom I was not expecting, seemed to have a message for me. Although not a biblical scholar, I was familiar enough with the Book of Genesis to know that I could not easily brush Abraham aside. I was remembering that the old patriarch had dutifully changed his name from Abram to Abraham, a sign that the mission of his life included more than he had previously realized. The God whom he worshiped had said: “Get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred, and from thy father’s house, unto a land that I will shew thee” (Gen. 12:1).3 As a young bride, I had changed my name, and as a social malcontent, I had yearned for a new country and a new way of life. In obedience to his Lord, Abram had “removed from thence unto a mountain on the east of Beth-el, and pitched his tent . . . , and there he builded an altar unto the LORD, and called upon the name of the LORD” (Gen. 12:8, emphasis mine).

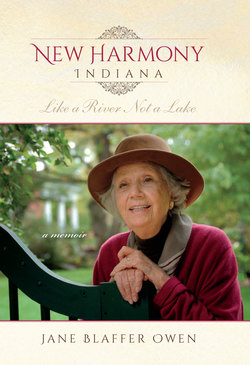

View of New Harmony and the Wabash River on the horizon from Indian Mound, January 7, 1936.

Don Blair Collection. Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Southern Indiana.

A pragmatic Hoosier sun did not dispel Abraham’s insistent presence on the hilltop or his companionship on the homeward walk. From an ancient mound an ancient prophet had communicated, not in an audible external voice but rather through an inward discernible intention. The implications of Abraham’s presence on the highest point above New Harmony were unmistakable: the buried treasures in the village below would never be fully discovered and shared until every endeavor was consecrated to higher purposes than mine. Had not previous plans of well-meaning people who had wanted to restore New Harmony always come to a standstill?

With unabashed self-righteousness before the entrance of Abraham, I had believed that the Lord would hear and bring to immediate realization my list of priorities, such as:

Buy and rehabilitate every available Harmonist house

Remove the Standard Oil filling station and reactivate the well nearby

that had supplied water to the town in Father Rapp’s day

Keep after Kenneth to secure options on the old Granary and the

Rapp-Maclure-Owen House on his block

Provide classes in dance, crafts, and especially ceramics

Make it possible for art, religion, education, and economy to join

hands and encircle our town

The jealous God of Abraham must have desperately wanted to widen and deepen my worthy but egocentric plans for the future, because He had chosen the right place and moment to do so. I was thoroughly shaken by the time Kenneth and I reached the Laboratory. Mighty chords of the Old Testament were ringing in my ears; listening, I knew I would have to reset my course and make myself very small before goals and thoughts higher than mine could flow into New Harmony. In good Texas vernacular, I had to be a pipeline, not the fluid.

Another Old Testament prophet, Malachi, also had advice for me: “ ‘Bring ye all the tithes into the storehouse, that there may be meat in mine house, and prove me now herewith,’ saith the LORD of hosts, ‘if I will not open you the windows of heaven, and pour you out a blessing, that there shall not be room enough to receive it’ ” (Mal. 3:10).

Trusting both Abraham and Malachi, I believed that, in time, there would be an altar acceptable to the Lord of Hosts, and once it was consecrated, blessings would “pour” into the village and beyond its borders. I was confident in a brief moment of certainty that I would be led to people who would help me keep the covenant with Abraham I had made on Indian Mound. Blind faith, yes, but not the wide-eyed faith that sees and counts solely on human blueprints and financial resources.

My nascent humility was tested a few years later, in 1948, when an undernourished but self-confident French intellectual stayed briefly at my first Harmonist house as a writer-in-residence. Not unreasonably, Dane Rudhyar voiced concerns about my endeavors and cautioned me like a policeman about to arrest me for driving without a license.

“Surely, Madame Owen, you have a master plan for the renewal of New Harmony?”

I cleared my throat to answer with minimal emotion but not glibly. “No, I do not have such a plan. I once made a list of needs for New Harmony, but I laid that list aside on Indian Mound during the spring of 1942. There is, however, a master plan in the mind and power of our Creator. If I stand still long enough, I can comprehend a few fragments; if I shut my eyes, I can catch glimpses.”

Many years later, I read Walter Nigg’s interpretation of words preached by the twelfth-century Cistercian St. Bernard of Clairvaux, which reaffirmed to me the need for balance:

For to him [Bernard], action and contemplation were not two contrary, mutually exclusive operations; they were organically linked together, like the flower and its stem. Contemplation that cannot be expressed in action is a self-consuming inwardness; action that does not flow from contemplation becomes a breathless driving that destroys the soul’s life. A man therefore must be truly penetrated with Christianity before he should think of throwing himself into active works. “Why do you act so hastily? Why do you not wait for light? Why do you presume to undertake the work of light before the light is with you?” And again, in another sermon: “If then, you are wise, you will show yourself rather as a reservoir than as a canal. For a canal spreads abroad water as it receives it, but a reservoir waits until it is filled before overflowing, and thus communicates, without loss to itself, its superabundant water. . . . Be thou first filled, then pour forth with care and judgment of thy fullness.”4

Thomas Kelly said it best, as indeed St. Thomas Aquinas before him: “Humility . . . rests upon the disclosure of the consummate wonder of God, upon finding that only God counts, that all our own self-originated intentions are works of straw.”5 My unearned income and unmerited grace were joined atop Indian Mound.