Читать книгу Bach and The Tuning of the World - Jens Johler - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

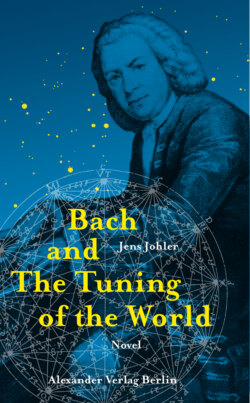

3. The Philosopher

ОглавлениеSimply to walk through the dam-gate and cross the huge castle square, the aspect of the mighty castle itself towering over all other houses on the square, filled them with awe. And the no less impressive figure of the philosopher now received them in the library! He was wearing a flowing wig with a plethora of black curls, a magnificent coat cut in the French style, silk stockings and silver buckles on his shoes. Erdmann froze in awe. Bach felt uneasy. He was tempted to bow and scrape in front of the distinguished gentleman and was only just able to hold himself back.

As the philosopher showed them through the rooms of the famous library, Bach was flabbergasted. So many books, thousands of them! And each and every one of them identically bound in expensive light brown calf leather with gilt engravings. The shelves reached right up to the room’s awesomely high ceiling, crammed with works of natural philosophy, moral philosophy and theology.

He was in the process of converting the library to a new system, the philosopher said. Up to now, the books were catalogued according to their more or less arbitrary location on the shelves. Now he wanted to establish a new principle of arrangement, in alphabetical order by the name of the author, from A for Aristotle to Z for Zwingli. It’s more practical. You’ll find the books more quickly and save time. Indeed, the era in which they lived was an era of reorganization and cataclysmic inventions. Had they heard of the calculating machine?

Erdmann nodded.

Bach shook his head.

‘Here,’ said the philosopher, and turned to a table on which an oblong object was hidden under a cloth. With a swift movement, he pulled away the cloth and revealed a golden sparkling machine that sported confusing details: on the top side of the apparatus, Bach recognized the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. They were arranged in a circle around an adjustable pointer in the centre. Eight such circles of numbers adorned the top side. They were connected to eight perpendicular number discs that apparently could be set in motion by a large crank.

‘The turnspit,’ the philosopher joked, and turned the crank. Le Tournebroche.

Confused and fascinated, Bach and Erdmann looked at the enigmatic apparatus.

The philosopher could hardly hide his satisfaction. ‘This,’ he said proudly, ‘is an invention that will change the world. No more stupid calculating. Addition, subtraction, multiplication, division – no longer a problem. Ten times as fast as when you do it with your head alone.’

‘And how,’ Bach asked doubtfully, ‘does it work?’

‘Take a look here,’ said the philosopher, and motioned for the two to come closer. ‘The most important thing is the graduated roller. The teeth have different lengths and are slidable. All the digits of the summand can thus be translated to the results mechanism.’

Bach scratched his head.

Leibniz laughed, amused. ‘With this machine, gentlemen,’ he exclaimed, ‘we’ll be able in the near future to calculate everything and represent it in formulas.’

‘Everything?’ Bach asked in astonishment. ‘With this machine?’

‘Of course not with this still very imperfect specimen,’ the philosopher said, ‘but with the principles on which it is based. Incidentally,’ he added, ‘I’m in the process of inventing a completely different type of calculating machine. Maybe the honourable gentlemen can guess what type of a machine I mean?’

Erdmann expressed his bewilderment in a sigh that was difficult to interpret.

‘Well,’ said the philosopher in a confidential tone, ‘it will be a calculating machine for words.’ Yes, they had heard correctly, for words and sentences, for discourse! To do so, however, the words, sentences and the relationship between them must be brought into a calculable form. ‘I call it the universal characteristic. As all budding young scholars very well know, all words can be built with the twenty-four elements of the alphabet. Right?’

Erdmann nodded.

Bach refrained from commenting.

So, Leibniz continued, in just the same way as words can be traced back to twenty-four simple elements, he would be able to trace back all thoughts to their basic ideas. He would designate each of these basic ideas with a symbol or number – and before you know it, we’d be able to express all our thoughts this way. Our language would then be as accurate and infallible as mathematics.

‘Fascinating!’ Bach had not wanted to say it, but it had escaped him. He had an idea but didn’t dare to speak it aloud. It had to do with the fact that the number 24 played a role in music as well. There were twelve notes and thus twelve keys, and if you kept major and minor apart, you got to twenty-four.

‘Yes, fascinating, isn’t it?’ said the philosopher. ‘When we argue about something in the future, we will no longer get lost in endless discussions, probably settling them with our fists. Instead, we’ll simply say: Calculemus! Let’s calculate!’

But, Bach said, having found the courage after all, couldn’t such a machine be built for music as well? For example, a machine for counterpoint: You enter a theme, and the rest will simply be calculated. Counterpoint, dual counterpoint, triple counterpoint, quadruple counterpoint, whole notes against whole notes, whole notes against half-notes, whole notes against quarter-notes and so forth?

His mouth open, the philosopher looked from Bach to Erdmann, from Erdmann to Bach. ‘But that is …’ he began.

Bach raised his hands apologetically. Probably he had said something very stupid, and he wanted to …

‘No, no!’ the philosopher exclaimed. ‘That’s a fantastic idea! I’ll suggest it to Leibniz immediately—’ He coughed and cleared his throat, pulled a lace handkerchief from the wide sleeves of his jacket and held it in front of his mouth. ‘I, Leibniz, will suggest it immediately –’ he began the sentence again in a slightly different order – ‘to the Society of Science in Berlin as soon as we have established it. It will finally take place in July. Maybe we’ll even advertise a prize question: Proposals for the construction of a machine that calculates every possible counterpoint variation for any given theme! – Excellent! What was your name again?’

‘Bach.’

‘Excellent, Bach! Especially since it’s not for nothing that we call music the calculating of the soul. It fits! Upon my soul! It fits perfectly!’

Bach should have been happy but was ashamed of the praise. He made an apologetic gesture to Erdmann, who nodded to him approvingly.

Unfortunately, explained the Privy Counsellor of Justice with an regretful expression, pulling out an object from which he seemed to be able to tell the time, his time was limited. He would now accompany the two gentlemen to the exit and then: God be with you both.

As they stepped into the open air, they had to shield their eyes from the blinding light. Only once they had got used to it a little did they see, against the light, a gentleman dressed in gold brocade ascending the flight of stairs. Was it the Prince? Bach noticed that the philosopher turned away, alarmed, and made a move to steal away.

‘Reinerding!’ the Prince shouted after him. ‘Reinerding?’ The man so addressed stopped in his tracks.

He had dressed himself up so much like Leibniz, the Prince said with a laugh, that he’d almost been fooled into taking him for the great man.

The other man now suddenly blushed violently and stammered something incomprehensible about a mistake in the calendar, and that Leibniz did not want to disappoint the students and had asked him to represent him, and so forth; and while he was still stuttering his explanations, he disappeared, side by side with the Prince, into the depths of the library.