Читать книгу Bach and The Tuning of the World - Jens Johler - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

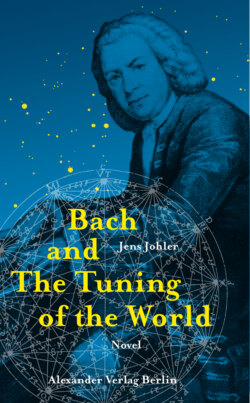

7. Adam Reincken

ОглавлениеHamburg!

Never in his life had Bach seen such mighty fortifications. No wonder the city had got through the Thirty Years War with almost no damage. The freedom and wealth of the Hanseatic League were, then as now, protected by this formidable bulwark. The price for it, though, was that the crowds in the city grew ever bigger.

It was nightmarish. They had hardly climbed out of the carriage when Bach had to fight an overwhelming sense of dizziness. The city was spinning round, the pavement wobbled, his heart was racing. He would have liked to turn back immediately, but Böhm had promised to introduce him to Adam Reincken, the celebrated organist of St Catherine’s Church.

They walked through the streets of the city, which was teeming with people. The city lay between two rivers and was cross-hatched by an abundance of canals they called ‘fleets’. Böhm walked in front, Bach behind him. He carried his knapsack on his back and his master’s heavy travel bag, transferring it from his right and left hand. The pavements were regularly laid with wooden planks, rotten in places, so you had to be careful where you stepped. And there was such a bewildering multitude of things to see! City Aldermen, riding by in elegant clothes, and cheerfully greeted on all sides; young women in modest high-necked dresses, their eyes cast downwards yet stealing flirtatious glances at passers-by; merchants going to the stock exchange in their carriages; noble ladies being carried in litters on their way to their tailor or perfumer. But there were porters, craftsmen, and labourers, too, and many, many poor people, clad in rags, who communicated in a language that Bach did not understand. The prevailing Babel of languages and voices jarred his nerves. This was not the normal jumble of dialects he knew from the weekly markets in Eisenach, Ohrdruf, and Lüneburg, but a hodge-podge of English, French, Italian, Dutch, and even Russian. Where was the keynote here, where the harmonic centre?

‘The keynote in this city is called money,’ said Böhm. ‘Pennies, shillings, florins, thalers, ducats, louis d’ors – the average Hamburg resident isn’t picky when it comes to money. These gentlemen are called money bags for a reason. They trade in pepper and other spices; and what they get for them fills their bags. Of course, they also trade in everything else that can be bought and sold. The greatest sin in this city is to be poor.’

In front of the magnificent town hall, which was counted among the city’s finest buildings, with its seven mighty double windows and its high tower, a woman had been set in the stocks at a rough stone pillar behind an iron grille. On her shaven head she wore a straw wreath, as a sign that she had committed adultery. Bach wondered what Erdmann would have said about it. Probably that such punishments were a disgrace, and that such things would no longer exist in a hundred years’ time.

The stock exchange was behind the town hall; then came a bridge over a fleet; and, shortly afterwards, they stood in front of St Catherine’s. Bach wanted to walk in immediately to take a look at the famous organ with the four keyboards, but Böhm didn’t let him.

Instead, he brought him to a section of the street called the ‘Zippelhaus’ because it served as a huge vegetable warehouse. The crowd was still pushing and shoving. Bach looked at the turmoil as though he were seeing it through a veil. He was not here at all. He was dreaming. His stomach was upset. The hustle and bustle of the teeming crowd nauseated him. On the other hand, it amused him that Hamburgers used the word Zippel, instead of Zwiebel, for ‘onion’! What a funny word! He made up nonce-words in his mind – a zippel-organist, a zippel-oboist – and he was still secretly entertaining himself – a zippel bassoonist! – when they ascended the stairs to their living quarters a little later. Two rooms, rented for three days, in an apartment that belonged to a singer. Instead of the singer, an old hunchback neighbour opened the door for them. Madame Petersen was not home, she said; she was at rehearsals. The gentlemen were likely here at the recommendation of Mr Reincken?

‘That’s right,’ said Böhm.

‘Well then, let’s go,’ the old woman said in her Low-German dialect.

The next day, Reincken received them. He cut a commanding figure: tall, well-fed, clad in a red silk-lined kimono tied at the waist by a cord. Above his mighty nose, his dark eyes were serious, melancholy, perhaps even a little suspicious. He’s gone under many times but has not yet drowned, Bach reflected – a thoroughly inappropriate thought that had probably only occurred to him because the master was just playing his grand chorale fantasia By the Waters of Babylon. And how he played it! The entire man practically exploded with energy as he sat there at the organ, whirring over the four keyboards with his hands and dancing the bass sounds from the pedals with his feet! Yes, you could only call it a dance. Especially since Reincken used such an unusual technique with the pedal, not only with the toes of both feet but by alternating between the heel and toe in such a way that the left foot was limited to the lower octave of the pedal keyboard and the right foot to the higher octave. Bach had never seen anything like it, not in Eisenach nor in Ohrdruf, not even in Lüneburg with Böhm.

‘Now it’s your turn,’ Reincken said, after he’d played the final chord and let it linger awhile, somewhat lost in reverence.

‘No,’ said Bach, ‘I can’t. Not now.’

‘Do you want to embarrass me?’ Böhm asked sternly.

‘He only acts the shrinking violet,’ Reincken said, all the while keeping his eyes focused on Bach. ‘Just let him sit down on my bench, then he’ll show us.’

And that’s exactly what happened. No sooner had he pulled the registers for a toccata in G major and sat down on the organ bench than his shyness evaporated. As he played, he was even more thrilled by the organ than when he had previously merely been listening to it. The beauty and diversity of the sound these pipes produced were extraordinary. Never before had he experienced such fine and distinct responsiveness, right down to the deepest C – no, never, not even with Uncle Johann Christoph in Eisenach. And the trombone in the pedal! No wonder Reincken had such a desire to dance on it.

When, towards the end of his recital, he saw Böhm smile and detected a hint of surprise in Reincken’s eyes, he even dared to play his own improvisation on By the Waters of Babylon, not to outdo Reincken – which would anyway have been absolutely impossible – but to pay homage to him. He didn’t have to blab it out, did he, that he had already made a copy of Reincken’s chorale fantasia in Lüneburg, and had often improvised on it?

There was silence when he finished. Bach turned around, gazed into the faces of the two old masters, and his despondency returned. What did this silence mean? He looked across the room to Böhm.

Böhm nodded reassuringly. But why wasn’t Reincken saying anything?

Reincken cleared his throat twice, and then said quietly, as though to himself, ‘He has to go to Buxtehude.’

Why? Bach wanted to ask. But he was unable to utter a word. Buxtehude was the greatest of all the organists and composers in northern Germany; a legend. Why did he have to go to him? What did Reincken mean?

But since Bach did not ask him, he didn’t get an answer.

‘What do you think of opera?’ Reincken asked instead.

‘Don’t know,’ Bach said hesitantly. He’d never been to the opera. There was no such thing in Eisenach. Nor in Ohrdruf, for that matter. Not even in Lüneburg. He knew from Böhm that Reincken sat on the Board of Directors of the Hamburg Opera.

‘You’ll get to know it tonight,’ said Reincken. ‘There’s room in my box.’