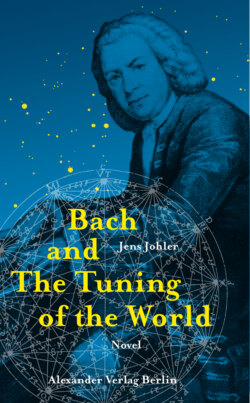

Читать книгу Bach and The Tuning of the World - Jens Johler - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. Departure

ОглавлениеOn 15 March 1700, shortly before sunrise, Bach set off.

Johann Christoph accompanied him to the town gate and, since the morning light still refused to break, part of the way beyond it. When they stopped on top of the mountain, they saw the sun sending its first rays across the edge of the forest.

‘Will you be all right on your own?’

Bach didn’t answer. Robbers and gypsies made their homes in the woodlands, waiting to grab his knapsack and violin. As soon as Johann Christoph left him, they’d pounce.

‘You’re shivering. Are you cold?’

He wasn’t cold, he was just shivering. He would immediately break into a run after his brother was gone.

‘Well, then, young ’un, God bless you.’

Bach returned his brother’s embrace and set off at a gallop.

‘Wait!’

Johann Christoph pulled a rolled-up bundle of paper from his waistcoat. ‘I almost forgot,’ he said. ‘Here, it’s yours now. Take it.’

Bach took a step back, staring at the bundle.

‘You want me to put it in your knapsack?’

While Johann Christoph untied his brother’s knapsack and stowed away the roll of paper, Bach furtively wiped a tear from the corner of his eye.

‘And work hard, always work hard, you hear?’

He nodded.

‘Why don’t you say something?’ And then, before finally setting off on his way back to Ohrdruf, Johann Christoph said in passing, more in a murmur than out loud: ‘Beware of pride, young ’un. There will come a time when you’ll surpass us all.’

Astonished, Bach watched his brother walk away. For five long years Johann Christoph had been his teacher, a strict teacher who uttered nary a word of praise for him. And now this? And what was it his brother had said? Was it a prophecy, a wish, a mission, or an order?

Just as Johann Christoph disappeared between the trees, the incandescent ball of fire rose on the horizon. Inwardly, a radiantly pure C-major chord resounded, soon dissolving into individual notes as if played on a harp. As he started on his way again, Bach whistled the arpeggio softly to himself. All of a sudden, his fear was gone. He thought of Lüneburg, of the Latin School, and of the famous Georg Böhm who played the organ there; he thought about the musical manuscript in his knapsack, and about his brother’s words. And while tears sprang once again to his eyes, he increased his pace, hurrying along so as to arrive in Gotha on time, where Georg Erdmann, his fellow pupil, was eagerly awaiting him.

Erdmann was sitting on a rock in front of the town hall and jumped up when he saw Bach. He was two years older than Bach, thinner and taller by a head. He, too, carried a knapsack on his back and instead of a violin, he had a lute slung over his shoulder.

He had been reading a lot in the last few weeks, said Erdmann as they left the city walls behind them, and had found his calling. He would become a philosopher, the greatest who ever lived. He would acquire all the knowledge of his time. Natural philosophy, moral philosophy, philosophy of law, everything! He had just read about an Englishman by the name of New-Tone.

Bach pricked up his ears. He liked the name.

‘This New-Tone, or Newton,’ Erdmann went on to explain, ‘is quite an eminent philosopher – some say, even more eminent than Leibniz, but that was for posterity to decide. Anyway, one day this Englishman was lying under an apple tree and fell asleep. And while he was peacefully dreaming away, he was rudely and suddenly awakened – by an apple, which fell bang on his head. He was angry and annoyed, and, naturally, he wanted to vent his anger at someone. But at whom? There wasn’t a soul in sight. After reflecting upon this for some time, the Englishman had a sudden inspiration on how all this was connected: the falling of the apple to the ground, the movement of the Earth around the sun, the movement of the moon around the Earth – and indeed all other movements that are not the direct result of an external impact. So there is a force inherent to all physical bodies, or at work in mysterious ways between them, without the bodies directly touching. And Newton called this magical force “gravity”.’

Bach was fascinated. Softly he said the word to himself: gravity; gra-vi-ty. The word fascinated him. The thought fascinated him that everything – the near and the far, the heavens and the Earth, the moon and the apple – was connected by a mysterious force. Gra-vi-ty: he tested various intonations of the word to get nearer to its meaning; he elongated the syllables, stretching them; he varied melody and rhythm; and the more lavishly he did so, the more he got caught up into the word; he stamped his feet, clapped his hands, snapped his fingers … until he noticed that Erdmann was looking at him with irritation.

‘Gravity,’ he said one final time, in an austere voice, with a gesture of apology.

Erdmann interpreted this as an encouragement, and began talking about Johannes Kepler, an astronomer who had postulated certain laws about the movement of the planets.

While listening to his friend with one ear, Bach heard the distant call of a cuckoo, and asked himself what it meant that it first sang a minor, then a major third. It sounded like farewell and loss.

Shortly before dusk, they arrived in Langensalza. A little boy, barefoot, in ragged clothes, followed on their heels. He showed them the high tower of the market church, and proudly explained to them that the stagecoaches, which had only recently started to stop here, went from Moscow straight through to Amsterdam. When they got to the house of Erdmann’s uncle, they gave the boy a pfennig, and he immediately scampered away, as though he wanted to get the money to safety.

The uncle’s house looked grey and bleak. Built of wooden beams and clay bricks, it had small crooked windows and a roof made of grey shingles. A cobbled courtyard could be seen through a high archway next to the house, and beyond it the smithy.

Erdmann’s uncle was the town’s blacksmith. He was a strong man with a powerful head and sad eyes. Reluctantly he showed Bach and Erdmann a place for them to sleep, and summoned them into the kitchen for the evening meal.

They ate the bread soup and the cabbage with millet gruel in silence. The house seemed to be ruled by some form of black magic that muted all words, all sounds, all thoughts. Bach could only feel a tormenting numbness in his head. Erdmann obviously felt the same. The uncle, however, thawed a little after a glass of brandy, without offering them any. ‘Who is your father?’ he asked Bach.

‘Ambrosius Bach, the town musician in Eisenach,’ he replied, but his father was no longer alive. He died five years ago, he said. First his mother, then his father.

His own wife had died too, the uncle said. Six months ago.

Bach nodded. He knew this already from Erdmann. The uncle had no children. He was all alone now.

When he hit the red-hot iron with his hammer in the morning, the uncle said, he sometimes didn’t know who or what he was hitting … May God forgive him.

Bach remembered how his mother had died. He stood next to the bed where she was laid out and imagined she was moving slightly, that she was breathing. ‘Wake up,’ he whispered, ‘wake up.’ He couldn’t believe it wasn’t in her power to do so. He was nine years old then. His father died a couple of months later. Still, he had had the good fortune not to be placed in an orphanage. His brother, who was the organist in Ohrdruf even then, took him in.

The uncle asked why hadn’t both continued at school in Ohrdruf.

‘They stopped the free meals for us,’ Erdmann explained. In Lüneburg, they would get everything for free. Accommodations, meals, classes. For that, they had to sing in the matins choir.

‘What nonsense all this is,’ said the uncle, and it wasn’t clear whether he meant the cancellation of the subsidized meals in Ohrdruf or singing in the matins choir in Lüneburg.

They slept on straw sacks in a room adjoining the kitchen. As he was falling asleep, Bach thought back on his time in Eisenach. What a joy it had been to hear his father play the little fanfares on the trumpet from the balcony of the town hall, or play at St George’s Church under the direction of the Cantor. What a joy it was to walk up with him to the Wartburg, where Luther had once found sanctuary, and to listen to him talking about how all creatures had their own melody – human beings, animals, even the plants. What a joy it was to play music together, along with all the apprentices and journeymen, who were always willing to show him what they could do on the violin, the lute, the trumpet, the clavichord. And what a joy it was to hear Uncle Christoph play the great organ – he who had mastered the laws of the fugue so perfectly that he could play five different voices concurrently without any difficulty at all. To be able one day to play as his uncle could – that had been Bach’s greatest wish from the very beginning.

Powerful hammer blows shook the house in the morning. Still half asleep, Bach imagined his own head to be lying on the anvil, and that the next blow was poised to split his head open. He leaped from the straw sack, slipped into his trousers and waistcoat, buckled on the knapsack, threw the violin over his shoulder and hurried outside.

Erdmann was ready to depart, waiting for him in front of the house.

‘Pythagoras,’ he said.

Bach threw him a questioning look.

‘Forging hammers,’ Erdmann said. ‘That’s how Pythagoras hit upon the secret of harmony.’

‘Ah, yes,’ Bach said. ‘I’ve heard about that.’

The further they walked into the countryside, the more people they met on the road. Farmers riding to their fields on donkeys or pulling sluggish farm horses by the reins. Children in ragged clothes, of whom it was hard to tell whether they were tramping to work in the fields, or else orphans seeking their fortune in the world before being picked up and imprisoned in the workhouse. Journeymen on the road, clad in their traditional garb. And time and again, beggars and thieves, distinguishable by their one amputated hand, or even their amputated hand and foot. On one occasion they overtook a lame man and a blind man, the blind man supporting his lame companion, who himself led his blind friend. Bach would have liked to give them alms, but he hardly had anything himself. Grand carriages rushed past them every now and again, and they had to protect themselves against any passing coachman who took it into his head to snap his whip on their backs just for fun. Individual riders also tore by them at full gallop, expecting that they would jump aside in time. Dodgy characters sometimes crossed their way, throwing covetous glances at their instruments – Bach’s violin and Erdmann’s lute. When asked for directions – which happened more than once – they had to confess they didn’t know their own way around there either. But at least Erdmann had written a list of the places they had to pass through on their way to Lüneburg. It was a pretty long list, and a pretty long journey.