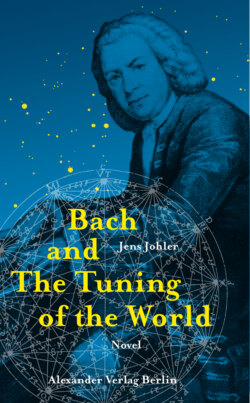

Читать книгу Bach and The Tuning of the World - Jens Johler - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

8. ‘That False Serpent, Opera’

ОглавлениеWhat an enormous theatre! Two thousand people could fit into the auditorium, and what seemed the population of a small town had crammed themselves in there this afternoon. Bach was mightily glad that he had a seat in Reincken’s box, and didn’t have to sit in the stalls among all the pushing and jostling, the laughter and chattering. The ladies and gentlemen in the boxes were festively attired in precious linen and silk, and lavish wigs. They drank wine and liqueur, and the ladies fanned themselves with well-practised movements. It was hot and stuffy in the auditorium, which was lit by a thousand candles and oil lamps. It smelled of a mixture of perfume, powder, burning wax and body odour; very few of those seated down in the stalls were dressed as finely as those in the boxes. If it had only been a matter of a choice of clothing, Bach would have belonged in the stalls. People exchanged raucous greetings across the rows. The gentlemen attempted to outdo one another with bons mots and jokes. The ladies rewarded their efforts with laughter and shrieks. Bach was glad when the lights in the hall finally went down, the noise subsided to a tolerable level, and someone backstage knocked on the floor three times with a staff or hammer.

The orchestra played a toccata, the auditorium settled, and Bach could hardly sit still from excitement and anticipation. The curtain went up, and now a landscape of forests and meadows appeared, beautifully illuminated, painted on numerous backdrops, a landscape of infinite expanse, where nymphs and shepherds gracefully reclined, chatted, and danced back and forth. No sooner had the general ooh-ing and ahh-ing abated than it started again when, on a throne decorated with flowers, a queen came gliding down from heaven, and this heavenly queen was none other than Lady Musica, who now began singing her aria.

It was the tragedy of Orpheus, the singer who stirred the emotions of people, animals, plants, even the very stones and rocks, with his singing. It was the story of Orpheus and Eurydice.

The music and dramatic action cast an immediate spell on Bach. He shared Orpheus’s happiness over his forthcoming wedding with Eurydice; he was painfully torn when he learned Eurydice had been bitten by a snake and died; his own hopes and fears went out to the singer, who descended and entered Hades to fetch Eurydice back; and he yielded to despair when Eurydice had to return to the Underworld because Orpheus had turned around to catch a glimpse of her.

Again and again, he shook his head in awe and amazement at how the audience’s imagination had been captured here with all the means of the many arts. The painted scenes, the stage machinery – Orpheus and Eurydice seemed to float up from the deceptively realistic cave and only used their feet when they had left the cave – the poetry, the music, and the acting all worked together here in harmony, in a perfect imitation of nature. The cornets, trombones, and the reed-organ represented the Underworld, and could always be heard when Evil and Death were dramatized on stage; the strings, flutes, and, above all, the harp represented the Upper World, and when Orpheus commanded the stage, the sound of the violins tugged at one’s very heart.

But most of all, Bach was moved by Eurydice. She sparked such a fierce longing in him that his chest tightened. Why do I feel this way? he thought. What’s happening to me? Is it Eurydice for whom I yearn? Is it the fact that I can’t accept her death that makes me burn for her? Do I feel with Orpheus because he, like me, is a musician? Or is it not Eurydice at all who’s creating such a painful desire in me, but rather the singer? I only know one thing: That I will never forget her, ever. I almost long to die so I’ll get to where she is already. Why did this Orpheus fellow have to turn around to look at her? Doesn’t he know that she’s following him? Doesn’t he have any trust? Oh!

After the performance, Böhm, Reincken, and Bach went to a coffeehouse not far from Gänsemarkt. That was a new experience for him, too. They drank coffee, an extremely bitter beverage that resulted – after being sweetened with lots of sugar – in a peculiar gustatory chord, dissonant at first but almost harmonious after the second or third sip. You had to drink clear water with it, though, otherwise your stomach rebelled. Allegedly, this drink was able to keep a man awake for nights on end. It stimulated the mind and, as was whispered behind closed doors, not only the mind. Some vilified the drink because of this; others praised it, almost canonized it, for the same reason. Bach found it exciting.

People were smoking, too, and thick clouds of tobacco hung in the air. Reincken also smoked. Böhm, by contrast, abjured tobacco and stuck to alcohol instead.

People sat at a long table, and were engaged in animated discussions. There were a few smaller tables, seating two, three, or four, but here there were twelve, all dressed quite differently – some in the elegant garb of the nobility, others in the plainer dress of the townspeople.

‘This is what makes the big cities special,’ said Böhm.

‘The classes mix and merge. Unlike at court, where only invited guests have access, anyone can go to the opera provided he pays the entrance fee; and the same applies to the coffeehouse. Everybody is seen as equal here, be he nobleman or burgher, and more important than his class or ancestry is what he has to say. Here is a place where even strangers meet to discuss and share what they have experienced and learned about the world.’

This evening, and in such company, the subject matter was, naturally, the opera. The performance was sharply criticized by some, highly praised by others. Soon, however, the focus of the debate shifted from the day’s performance to a scrutiny of the notion of opera itself. In particular, one gentleman, dressed in a black frock coat and wearing a severe white wig, stridently called for the immediate closure of the opera house.

‘It’s a scandal!’ he shouted again and again, his right index finger stabbing the air like a stiletto. ‘The opera should never have been invented! It corrupts the young. And not only them! It is destroying the musical life in the city.’

‘Joachim Gerstenbüttel,’ Böhm whispered to Bach, ‘the Cantor at the Johanneum, and the city’s Musical Director.’

‘It ruins the entire musical life here in our city because it spoils the prices for the musicians,’ Gerstenbüttel continued. ‘In the meantime,’ he shouted, ‘it’s hard to find singers and instrumentalists for good church music because they all get hired by the opera! And apart from payment – how can you let a singer perform in the church who the very next day will be prancing about on the opera stage as a pagan god! Today, he sings for the glory of God – tomorrow he’s in the service of a godless pleasure. That’s nothing but a mockery of the Holy Mass! It has come to the point that some serving-wench actually sang from the gallery at St Jacob’s!’

‘What a galling gallery!’ somebody shouted, and everybody laughed.

‘Yes, laugh, laugh!’ the Johanneum Cantor exclaimed, jabbing his index finger towards the joker. ‘I see I’m surrounded by opera lovers! The glory of God doesn’t weigh much any more in this city. Even from the pulpit, that false serpent, opera, is paid homage to! The obsession with the worldly vanities of France and Italy is usurping the love for our Lord Jesus Christ! Everybody’s ears itch for the opera. As if you all had nothing more urgent to do than go to hell – this very day!’

A gigantic swelling of voices rose up, dominated by loud cries of abuse, intermixed with a few timid approving comments. Gerstenbüttel fell silent. He made a helpless gesture, sat down, then looked around him, filled with bitterness.

Bach wondered if he should get up and say something in the Cantor’s defence. Although he could understand that we all had eager ears, and even eyes, for the opera, there was a difference – wasn’t there? – between playing serious and godly music, and the merely pleasing entertainment that music can offer people. He would have liked to say a couple of words publicly on this difference. Maybe he could mediate between the parties, such as to restore harmony to the noisy group. He got up, wanted to call out with a clear voice, ‘Gentlemen! Gentlemen, just a word,’ but when he wanted to open his mouth, all he felt was his head turning bright red.

‘Gentlemen, a word, if you please!’

From the tangle of voices came the clear, bright, and radiant voice of a young man who had stood up at the same time.

Bach took advantage of the moment to quickly sit down again. Nobody seemed to have noticed him, not even Böhm and Reincken. Everybody looked at the young man. He was scarcely older than Bach, with a broad face, a straight nose, and a nicely curved mouth that constantly seemed on the verge of smiling. His head was framed by a billowing white wig, with curls and ringlets, and he wore an elegant silk scarf around his neck à la française.

Bach didn’t understand everything the young man said. The subject of his speech was odd to him. What did it mean that music had to be ‘gallant’? Gallant? That was something for the sons of noblemen visiting the Knights’ Academy, surely? Their ideal was, as he knew from Erdmann, the galant-homme, learned, of good taste, and well-versed in all gentlemanly arts. But what could this word possibly mean in a free town of citizens such as Hamburg?

The young man was not thinking about courtly gallantry, however, when he used the word. Instead he demanded a new understanding of a gallant way of life and of gallant music, he said. Gallant, as he defined it, meant educated and prudent, open and understanding, capable – truthful, even. Gallant, he said, was everything it means to be in tune with nature.

‘Yes,’ he said, and smiled subtly. ‘It is truly gallant when the inward and the outward match.’

‘Especially when it comes to women!’ some joker shouted out.

Unperturbed, the young man continued. ‘And that is how music ought to be. It’s not enough to get the melody and the harmony right. There must be a third element, a certain indefinable something, the je ne sais quoi, and that is what I mean when I say that music should be gallant!’

There was quite a bit of applause at this little speech – not solely because of its content, perhaps, but also due to the fact the young man had mastered the rules of rhetoric so well.

Bach, by contrast, felt stricken. The je ne sais quoi – was it that quality that Böhm had said his playing lacked? He stole a glance at his teacher, who sipped his drink, his face impassively unimpressed. No, he thought, this je ne sais quoi was something different from the harmony of the world that was so important to Böhm. That gallant something – the expression shot through his mind – belonged only to this world.

The applause was still rippling on when the Johanneum Cantor again stood up and thundered a terrible ‘No!’ over the assembled heads. ‘No, Mattheson!’ he repeated, slightly more quietly. ‘The third element is not the je ne sais quoi, but our necessary reverence before God, our Lord, and His creation! Remember it when the bell tolls for thee! Remember it when the Devil comes to get thy soul!’

And with this, his whole body shaking, he left the coffeehouse.