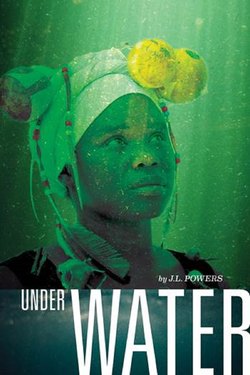

Читать книгу Under Water - J.L. Powers - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

LUCKY

When they are gone, Zi and I clean the mess. The women did dishes and packed up the remaining food—at least Zi and I have plenty to eat for the next week—but they left big piles of rubbish in the yard, which are already attracting flies. Zi and I pile the rubbish into several bins and cover them with a tarp. I can handle snakes or fleas or monkeys, even flies I can live with, but I hate rats.

“What do you suppose Gogo is doing right now on the other side?” Zi asks.

I shake my head. I don’t have to suppose. I already know. “She and the other amadlozi are sitting around gossiping about the funeral,” I say. “Gogo is laughing about how many people came for a free meal, people who never visited when she was alive.”

Zi shakes her head. “That isn’t funny,” she announces. “I’d be angry. What good is it to come pay your respects after somebody dies if you never visited when they were here with us?”

“The things that matter to us when we are alive are not so important when we are dead,” I say. “Gogo is glad they had a good meal. And she’s touched by how many of them brought money to give to us.”

Neighbors and friends, far and wide, gave what they could. 10 rand here, 50 rand there—it adds up. Most of it already disappeared to pay for the funeral expenses. What is left, Auntie and Uncle took a share of and left some few rands for me and Zi. They must feel they couldn’t leave us with nothing, and yes, they were her children so they deserved something, probably the lion’s share, which in fact they took. But it showed us, Zi and I are now on our own. We won’t see any help from them for school fees or any other such needs.

“But don’t you think Gogo is sad not to be here anymore?”

“She doesn’t even miss us,” I say. “She sees us anytime she wants. So if you ever want to talk to her, just say, ‘Sawubona, Gogo!’ Even if you can’t hear her, she’ll hear you!”

The look on Zi’s face is one of pure horror. “No thank you,” she says. “Does she really see everything?”

I suppose that is a scary thought for those who do things they shouldn’t do. But I’m used to it.

The gate rattles and jangles. Little Man’s outside, shaking the fence to be let in. I send Zi out with the key to unlock the gate while I haul a mattress from the bedroom to the living room so we have something to sit on.

I look up and Little Man catches me in a hug. He’s like a Cape Holly or a lavender tree, he’s grown so tall—tall but very thin, while I am short with lots of curves. I like the way it feels as his hand slips around my waist. And I still love his dark blue-black skin, just as much as when I first noticed it three years ago. “S’thandwa, how are you?” he asks.

I sink into him. This man. “Ngikhathele. How are you?” I ask. Instantly, I feel better as I hear his heart beating against my ear. He drapes his hand around my shoulder, his face close to mine, cheek to cheek. Perhaps I am not so tired as I seemed.

“I was just that much sorry not to be able to help more with the funeral,” he says. He looks around the room. “Eish, it’s empty. Relatives stole your furniture, eh?”

“They are angry,” I say. “They think I killed Gogo.”

He shakes his head. “Wena, you killed Gogo? They’ve gone mad, Khosi. How could they even think such a thing?”

“I don’t know what to do,” I admit. I know it makes you sad, Gogo, but I think they will have very little to do with me or Zi after this thing. I am sorry, I wish I knew how to heal this rift.

“Where’s Zi?” I ask.

“She’s outside with a little surprise.” Little Man bursts out laughing. I’ve always loved his laugh. It booms out, like it’s coming from a place deeper inside him than words. “Something I’ve brought for you.”

“What?” I ask. Then, when he doesn’t answer, “What what what?”

And then Zi is there opening the door and giggling and then she’s running out into the yard with a little brown yapping thing biting her ankles and barking.

“What is this thing?” I ask. “A puppy? Why are you bringing me a puppy?” Gogo! You never let us have a dog and here you are, some three days gone, and I’m already breaking one of your rules. At least, this is not a rule you made me promise to keep.

Little Man has a sudden pleading look in his eyes. I already know what that look means, the content of his unspoken question.

When Gogo got sick, and we knew what was coming, it was something the two of us talked about, dreamed about. Being a family. Being together, all the time, living together. But Gogo made me promise to finish school before Little Man and I became serious.

But Gogo, how can you wait to get serious about somebody? Either you are or you aren’t. And we always have been serious about each other, from three years ago, from the first time we kissed.

Plus, we never talked about what I should do if I was unable to finish school. What if I can’t pay the school fees. What then? Am I never allowed to get serious about Little Man? Eh, Gogo?

“You know the answer is no,” I say. “You cannot live with us. Not yet.” I watch Zi, running after the little brown dog. She looks back at me, delight in her eyes.

“Eish, Khosi, do you think that’s all I think about?” he asks, but a small part of the light inside his eyes dies. “I know we must wait until after the cleansing, at the earliest. But could you promise to think about it?”

I keep my eyes on the puppy and Zi, not wanting to focus on his pain. I want it too. Mkhulu, can you talk to my Gogo and ask her why she made me promise this thing? “Ehhe,” I say. “Of course I will think about it.”

The ritual cleansing after a loved one dies takes place some few weeks or months after their funeral. During that time, there are some few things you should not do, like drink alcohol, or you will not be able to stop doing that thing. Even if you don’t want to do that thing, you will just keep doing it. You have no reason left, you are just an animal, doing what you do. So the cleansing has bought me some time to shield myself from Little Man’s request.

“Anyway, that’s why I’m giving you this dog,” Little Man says. “You and Zi are too much alone. She will protect you. And did you know this dog chose us?”

“Eh? Is it?” I kneel down and call the puppy over with my tongue, tch tch tch tch. She joggles over and sits in front of me, tongue protruding, head tilted to examine us. She licks my hand as I look her over. She’s nondescript, clearly a mutt, brown hair with black markings around the paws. She looks like she will grow up to be fat, one of those dogs that lays in the sunshine and barks ferociously at whoever walks past but then, if someone actually comes in the door, she’ll waddle over to lick their hand. “Why do you say she chose us?”

“I was driving to Maqongqo to visit Baba yesterday,” he says. “I was sad, thinking about your grandmother’s death, and the funeral today. I didn’t have my mind on driving. You know that part in the road when there’s nothing but bush surrounding you as far as the eye can see? One of those bends in the road when you know you’re kilometers away from where anybody lives—and you think maybe just now a lion will jump out in front of the car?”

“Yebo,” I say. I love roads out in the middle of nowhere like that. It makes life seem wide-open with possibilities—not the closed-off feeling I sometimes get here in Imbali, with so many houses and people, you can’t even see past your neighbor’s house.

“Well, it was just then that I realized I had a flat.”

“Haibo! Did you have a spare?”

“That’s why I stopped. I got out to change my tire. And there she was, on the side of the road, poking her head out from the bush.”

“Shame! How did she get way out there?” I ask.

“Who knows? Maybe somebody abandoned her. Or she walked there, but it must have been 50 K to the nearest house. Let me ask you, why did my car stop just then? At that exact spot? I will tell you why. Because she was waiting for me. For us.”

We look at each other and then we look at the dog. And this is the thing: she looks guilty, like we’ve caught her out or something. Like she has chosen us, as Little Man says, but we weren’t supposed to figure that out.

Gogo, I know you didn’t like dogs. You said they were dirty creatures and belonged in the wild, on the savannas, not in our homes. Dogs and Zulus, you said, do not belong in the same hut. But I always felt vulnerable the way we lived, an elderly woman alone with two young girls. And now you’re gone. What am I supposed to do? I need protection.

I know that tsotsis could just shoot a dog and come inside two seconds later and we’d have to face them. But I hate most the idea that I will have no warning, that death will be a surprise. I’d rather know I’m in danger than never see it coming.

“Will you take her?” Little Man says. “And it will make me feel you are safer, until the day when you say yes, and I can live with you.”

Zi comes over and stands by the puppy. She tangles her fingers in the puppy’s fur, looks at me with dark pleading eyes. How can I say no?

“Her name is Nhlanhla,” I say. Lucky. She is lucky after all. Just because Little Man came along the road that day, she escaped certain death in the bush. She would have starved or been eaten by something bigger than her.

“Zi, don’t just stand there,” I say. “Go get her something to eat.”

So her first night with us, Nhlanhla feasts on funeral food. “Don’t get used to it,” I tell her. “This is not how we normally eat.”

She seems so smart, and her brown eyes—they look just like yours, Gogo.

“It’s time for soapies,” Zi says, hopeful.

So we turn the TV on. The three of us sit on the mattress, backs against the wall, the light flickering as we watch Generations, Isidingo, and The Bold and the Beautiful. Nhlanhla cavorts around the living room as Little Man reaches behind Zi’s back to hold my hand, and I sit there with his hand in mine, feeling not quite so alone.