Читать книгу Under Water - J.L. Powers - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER NINE

MEDICINE OF A SORT

After sending Zi to school, I stop at the tuck shop and part with a few precious rands for a cool drink.

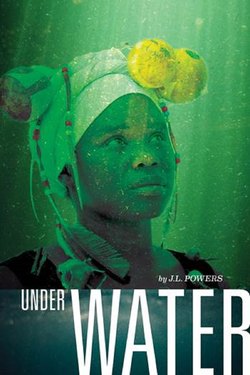

The tuck shop on my street used to be owned by a man who lived just next door to the shop. But he sold it to a Somali family some few months back. Occasionally, the wife is here, wearing her long skirts and bright red or pink head coverings, her children hovering in the background, sucking thumbs or candy and staring at me. But most of the time, the husband runs the shop. I don’t know where they live but it’s not in Imbali—I’m sure they live far from here, probably because they worry all the time that they will be attacked. Now we slide rands through a small hole in an iron grid meant to protect the man inside from weapons. That’s because he’s already been robbed at gunpoint twice, and he’s only been in Imbali for six months!

The Somali-run tuck shop isn’t the only change in Imbali. A Chinese herb and healing center opened just a short, ten-minute walk from my front door. Makhosi says not to worry. “Even if people try this Chinese stuff,” she says, “they’ll always come back to sangomas. Nothing can replace hearing from your own loved ones who have passed on to the other side. You think those Chinese healers can hear our dead? No, they may have magic herbs but you must be Zulu to do what we do.”

Even if they don’t hear our ancestors’ voices, people are seduced by the Chinese: they respect healers who have come from a long ways away. It seems like people believe that the farther away it comes from, the better it must be.

At least, when it comes to medicine.

They don’t feel that way about Somalis or Chinese who own tuck shops and grocery stores. I don’t blame this man for putting up bullet proof sliding where he takes the money, or keeping himself locked in all the time. It wasn’t so long ago that people dragged Somalis through the streets in Durban, killing them for no other reason than that they run the tuck shops so, according to the people, they must be taking away jobs from South Africans.

I greet the man in Zulu, “Sawubona, Ahmed, nina ninjani?” Then in Arabic, “As-salaam ‘alaykum.” I want him to know that he has nothing to fear from me. I’m perfectly OK with his presence here in the township. No matter how different—or similar—he is.