Читать книгу Under Water - J.L. Powers - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

ACCUSATION

We make a procession from the cemetery to the house, walking up and down Imbali’s dirt roads. Winter is dry, the roads covered with a thick centimeter of reddish-brown earth. The morning haze has lifted, cold air gradually giving way to the heat of day.

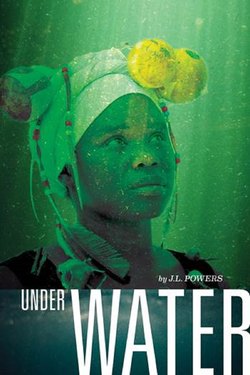

Most of the neighborhood and all of my grandmother’s family are here, dressed in their funeral best. Mama’s sister’s family walks in front of us, Auntie Phumzile dressed in her Zionist church service finery—a white turban wound around her head, white blouse and green skirt, a maroon cape wrapped around her shoulders. My cousin Beauty, too, is dressed in an expensive new dress, and she walks with her head held high. She barely acknowledged me when she arrived. My mother’s brother is dressed in his finest suit and he carries Mkhulu’s walking stick, my grandfather’s staff that was passed down to the new patriarch of the Zulu clan when he died.

Zi and I are wearing simple, everyday clothes, like Gogo requested—white, her favorite color.

My neighbor MaDudu walks alongside us and clucks her tongue. “Didn’t you and Zi buy new clothes for your grandmother’s funeral?”

“We didn’t have the money,” I explain. “Anyway, Gogo chose these dresses for us to wear to her funeral. They were her favorites. She said she lived an ordinary life and she wanted her real life honored in that way.”

I remember her smile as she told me, “You arrive Mr. Big Shot but leave Mr. Nobody. I don’t need an expensive funeral, eh, Khosi?”

“Shame,” MaDudu says, agreeing with my decision, and nods her chin at Auntie Phumzile. “But that one, she will say you aren’t showing proper respect.”

Of course MaDudu is right. Auntie will say these things, but she will be wrong. This is how I offer respect to Gogo—by following her wishes. And by keeping my promises to her, even though, only seventy-two hours after her death, it seems impossible.

We turn the corner to our street and I stop for a moment, just to look at the people coming to mourn Gogo.

In the past week, our yard was transformed so that we could host the neighborhood—a neighborhood Gogo has lived in for some forty years. We erected a large tent where neighbor women have been preparing the funeral meal. Already, the neighborhood is queuing, a line of people stretching from the gate to the spaza shop two doors down. The scent of fried chicken, rice, phuthu, and cooked kale hits my nose long before I reach the yard.

It feels like a betrayal to Gogo to be hungry but it’s true, my stomach is growling. I need to eat now now. I have had just one or two slabs of phuthu with a little bit of amasi since she died, three days ago, a fact that Little Man has pointed out, worried that I’m going to collapse. “You need to eat, Khosi,” he urged me. “To keep your strength up for all you must face.”

But how could I eat, hearing all the rumors and accusations?

I grip Zi’s hand even tighter. I can’t forget Auntie’s face, her lips curling, her nose twitching in sudden sneezes as she demanded the right to go through Gogo’s things and take what she wanted. “I am her daughter, I should have her clothes,” she claimed. “It is tradition.”

As a sangoma, everybody believes that I revere and respect tradition more than anything else. But I must tell you, sometimes tradition cloaks thievery. Not that I cared about Gogo’s clothes, but I would have liked to keep the simple beaded jewelry and headdress, just to remember her.

Instead, I have the house to remember her by, which presents a different problem.

For now, though, all I must think about is making it through the funeral.

Zi and I stop first at the washing station to clean our hands before we enter the house after having visited the gravesite. Inside, family members are already feasting. I scan the queue for Little Man and his parents. To me, and to Gogo, Little Man is family but I understand that nobody else recognizes that—yet—so he must stay outside with the others. Maybe someday the rest of my family will understand that even if we are only 17, we have been together for three years, ever since Mama’s death. He is much more than a boyfriend.

Inside, there are no places for us to sit except the floor, so we take a corner and wait for one of the ladies to bring us plates of food. I suppose we better get used to sitting on the floor. Auntie also claimed the sofa in the living room and the table in the kitchen. I’m hoping my uncle will step in and tell her no. No, no, you cannot leave Khosi and Zi with nothing. This is their home too… that is what I hope he will say.

Auntie flounces over to the floral sofa she wants. She sits with a big plate of food balanced on her lap, glancing at me from time to time as she chews the meat off a bone.

“Mm mm, I’m just saying, why did my mother die so suddenly after she made a will and left the house to Khosi?” She is talking to Gogo’s niece from the Free State, who drove all night to get here for the funeral.

“Sho, is it?” The niece bites into a hunk of meat.

I put my plate of food down on the floor, stomach churning. What’s going to happen after all the food is eaten and the neighbors go home? What will Auntie say then? Or do?

“I’m sure Elizabeth’s daughter would never harm a soul,” the niece says. “I know Khosi is a sangoma but she doesn’t practice this thing of witchcraft, does she?”

“I never thought so, not while Mama was alive.” Juice drips down Auntie’s wrists as she mixes gravy with phuthu and scoops it into her mouth. “But you never know with sangomas, not these days. It is very suspicious that my mother died so soon after she wrote that will.”

“What what what, you really believe she is umthakathi?”

I can’t listen to this. “Come, Zi,” I say, and we stand and walk out of the house. As we pass, my aunt cackles under her breath, knowing she’s scored a point against me.

I slink outside, an unwanted dog in my own house. The crowd of people waiting to eat is as long as ever and the yard is already festering with trash and flies. This is going to be some clean up job… I only hope my family members, the vultures who have descended for food and a chance to take all of Gogo’s things, will stay long enough to help me clean up.

I wait in the yard, saying goodbye to neighbors and friends as they leave. “Hamba kahle,” I tell yet another neighbor, who looks satisfied by his big meal.

“Sala kahle,” he responds.

The priest who spoke at the funeral takes my hands gently in his. Droplets of sweat glisten in his short, wiry hair. He must be sweltering in those dark priest’s robes.

“Baba,” I greet him.

The fact that I am a sangoma lays between us, unspoken. I have never felt that I couldn’t be both Catholic and a sangoma, I have never felt there was a contest between God and the amadlozi, but I am not sure that he—or other priests—feel the same way. And it is true that God is silent and the amadlozi speak to me all the time. Why would God choose to be quiet when I know he could speak? So perhaps there is some contest after all. I am not sure what to do with this split in my heart.

“Khosi,” he says. He lifts a hand and lays it on Zi’s head. “I trust that we will see you and Zi at mass on Sunday, like always. That you will be as faithful as your grandmother was all her life.”

“Yes, Baba.” I skirt his eyes to look at the sky.

Zi gives him a hug. He makes a rumbling noise in his throat, a little sound of love and affection, and perhaps some sorrow too.

“I’ll be praying for you,” he says.

“Hamba kahle,” I say, in return. I’m glad for his prayers. We need them more than ever.

After everyone is gone, Auntie sends her husband to borrow a friend’s bakkie so they can take Gogo’s sofa with them now now.

“It’s OK, Auntie Phumzi,” I say. “It is late. Come back tomorrow. The sofa will still be here. It is not going to disappear overnight.”

She laughs. “Oh, no, by then you will bewitch it. I must take it now, before you do something evil like you did to my mama.”

“I would never hurt Gogo,” I say. I look from Auntie to my cousin Beauty and then to my uncle Lungile. “Beauty?” My cousin and I have always been different, in many ways, but she and I are close in age and played together growing up. I would like to think she is an ally. “Uncle?”

The awkward moment stretches out like a pot of phuthu and amasi that must feed too many mouths.

“Let us just focus on the future,” Uncle says finally. He scratches his head, as though trying to distract us from what he is saying. “Let us leave this thing behind us.”

“What thing?” I ask. “This thing of Auntie accusing me of something I would never do? Do you really think I would hurt Gogo? Gogo, the only mother I had after my own mama died?”

“Nooooo,” Uncle says. “But you must listen to your auntie.”

It is nonsense, what he is saying. If I did not kill Gogo through witchcraft, but that is what she is saying, why must I listen to her? I can see I have lost my family through this.

“Take what you want.” I am angry now. It burbles up in my chest, the same anger I once felt towards Mama when I realized she stole money before she died. “I do not care about things. I have Gogo’s spirit with me, which is more than you will ever have. And I have the house, you cannot take that.”

Somehow those words take Auntie from one thing to another, and in seconds, she is screaming. “We’ll get the house back, you little witch,” she yells. “You don’t deserve it! You killed her!”

“Phumzile!” Uncle Lungile shouts. “Quiet! You can’t say these things, Mama is just now buried… Please, let this thing rest.”

“Auntie,” I say, pleading with her. I try to catch her eye but she refuses to look at me. “We are family. We are blood. Please, let us just let this thing go away.”

But she won’t stop. She’s in my face, shouting. “It will never go away!”

Suddenly, I’m no longer afraid. None of the others can see Mkhulu or Gogo in the corner, but I can. They are shaking their heads—at her behavior, yes, but also at me, warning me to let this go, not to retaliate. So it’s true, I’m not afraid. But my calm seems to convince her more than ever that I am guilty. I reach out to touch her forearm, to soothe her.

She jerks her arm away and raises her hand to slap me. “Hheyi, wena, you think we don’t know what you have done? Hah!”

My cheek tingles from her slap. But the hurt feels good. Not like this thing of Gogo’s death, a sting that will never go away.

“What is it you think I have done?” I say.

She spits in my face. “You killed her! You killed her!”

Uncle Lungile grabs her by the arm and hauls her outside. She’s still shouting, and all the neighbors are gathering to watch. “Haibo! Go away or we will give you something to talk about,” Auntie yells at them.

They move further up the hill but none of them stop watching. It is too good, this scene of family disarray. Even MaDudu stands and watches this thing of my aunt accusing me of witchcraft.

There are people who think it is powerful for others to believe you have a witch working for you, and I know there are those people who will seek my services if they believe that is what I do. But it is dangerous. It is not some game to play.

A long time ago, around the time Mama got sick with the disease of these days, MaDudu employed a witch to curse our family. She did it because she was angry. To our shame, my mama had stolen the insurance money after MaDudu’s husband died, something we did not discover until after Mama died and I found the money she had hidden in a secret bank account. It has sometimes made me wonder if Mama can even be an ancestor, the way my Gogo and Mkhulu are. Yes, I watched her join the rest of the amadlozi when she died, and I often see her in the crowd that follows me around, but she never speaks to me. I never ask her for help to heal. I wonder if she even can help? Do the things we did or failed to do on earth prevent us from being fully what we should be on the other side too? I wish I knew. It’s something I’m working out.

Auntie and Uncle stand a long time in the yard talking. Uncle holds her by the arm as if trying to prevent her from running away. She is talking so angrily, she doesn’t even notice that her turban has come askew.

Her husband arrives in a borrowed bakkie and Uncle Lungile comes inside and says, “Khosi, the house is yours but you must leave just now. She will not come inside if you are here but it is our tradition for her to take her mother’s things.”

So Zi and I stand in the back yard, near the washing bins where we wash our clothes, while Auntie and her husband haul away the sofa and the table and chairs. They pack away most of the kitchen items, but leave us some few plates and forks and a pot for cooking. They leave us the beds and mattresses, for which I am grateful. And the TV. Perhaps they leave the TV because it is old. Their TVs are all new and this one wouldn’t even fetch a good price if you tried to sell it in the streets.

And then they leave, all of them, they do not even come to the back to say goodbye or tell us they are done.

I wonder if they will be back for more or if we have seen the last of them.