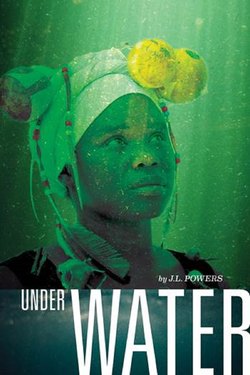

Читать книгу Under Water - J.L. Powers - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FIVE

THE CLEANSING

The empty house feels even more barren, stripped of most of the furniture and all the wall decorations and the crocheted lace that Gogo draped in various spots around the house. I hope Auntie is enjoying everything she took in her already over-decorated house.

When I think enough time has passed and I still haven’t heard from them—not about the cleansing, not about life, not about school fees or help with what what, nothing—I visit my teacher, Makhosi. We must talk about launching my healing practice, especially if I must begin to earn a living.

Outside of the hut, her granddaughter Thandi stands in front of the washtub, plunging her arms deep into the sudsy water, apparently washing a load of clothing. She drips water on my shirt as she gives me a quick hug.

Thandi’s little girl Hopeful is running in circles in the courtyard just inside their yard. Her mouth is sticky, stained red with some kind of candy.

“Are you coming to see me or is this a professional visit?”

“I’m sorry, I came to see your grandmother.” I smile ruefully at her.

Thandi used to be my best friend. She and I have known each other almost our entire lives. But then she fell in love with an older man, Honest, who was anything but honest.

In truth, I haven’t been the best friend to Thandi since Hopeful was born. First, I was training with her grandmother and going to school at the same time. Then Gogo got sick and died and now, it’s just me and Zi, so I don’t see how it’s going to be different—I’m going to be responsible for a whole lot more now that Gogo isn’t the adult. All this time, I’ve been trying hard just to manage everything. Besides, Thandi’s entire life is so different than mine now. She quit school long before I did to take care of her baby. She and Honest stayed together for a short while but then he returned to his wife so she came back home. And now she’s raising Hopeful alone, with her family’s help, of course. It sometimes feels like we’re both hiking a steep trail but the path is taking us up two completely different mountains.

“I’ll tell Gogo you’re here,” she says.

“Ngiyabonga.”

“Maybe after you can stay for a cup of tea and play with Hopeful?”

“Yebo.” I nod my agreement.

Makhosi taught me everything I know. She trained me to be a sangoma. When she gestures, I enter her hut and breathe in the rich scent of impepho.

“Makhosi.” I greet her with the honorific title.

“Makhosi.” Before I became a full sangoma, when I was her junior, her student, she called me thwasa. Now she greets me as makhosi, her equal. Sometimes, now that people greet me the way they greet all sangomas, with a strong “Makhosi!,” it feels as though my given name “Nomkhosi” with the nickname “Khosi” was nothing more than a prediction of my calling, of what I’d become someday.

I wait a few seconds in silence, out of respect. I expect her to ask me what I’ve come to ask her. But before I can talk to her about launching my practice, she reminds me that it’s time to do the cleansing for Gogo.

“It’s your duty,” she says. “You must perform ukugeza. Then you can start your life. Your grandmother is waiting for this to be done. I can see her, can’t you see her? She is crouching behind you, ashamed that her children have forgotten.”

“I haven’t forgotten,” I say. “But I haven’t heard from my aunt and uncle in three weeks. What if they don’t want to do it? Or don’t want to do it with me?”

“You do it on your own,” she says, simply.

So I try calling Auntie and Uncle but neither answers the phone, nor do they call back. I text—We need to do ukugeza, I am planning to do it, are you both coming?—and hear only silence in return.

But you can’t wait forever to cleanse the hut. At some point, life must return to the living. Even sangomas know this, we who are always with one foot in that world and one in this.

What should I do?

Go to her, my child, Mkhulu says. Your Gogo is here with us but she must have peace. Your Auntie Phumzile has forgotten tradition.

But what Mkhulu doesn’t say, is this thing of accusing a relative of witchcraft—that is also tradition. Not real tradition. Not like a wedding or a funeral, where you can say, This is how things are done, nee? You have the food so, and the people so, and the impepho so, and here is where the amadlozi sit, and you must, you must, you must. But even so, these accusations, they happen all the time. What do you think of that, Mkhulu? Is that tradition, hah? Sometimes I am not so sure about “tradition.”

Thandi and I have a quick cup of tea after but Hopeful is misbehaving, chasing after the dog and knocking into one of her grandmother’s customers waiting in line, an elderly gentleman sitting on a broken chair. He wobbles for a second and then totters over, so slow it’s almost comical.

“Oh, Mkhulu,” I say, “let me help you up.” He grips my offered hand and I raise him to standing position.

While I’m helping the old man, Thandi is already yelling at Hopeful and chasing her through the yard and into the house to swat her bottom.

I wait some few minutes, then tell Thandi I’ll come by again soon. I’m so glad I’m not a mother yet.

That Saturday, Zi and I walk to the other side of Imbali to Auntie’s house. They are home, I know this because her husband’s car is there, and Auntie doesn’t drive, but we rattle and rattle the gate and nobody comes out. We wait and wait. The sun beats down on us. We rattle again and wait. The dust rises and settles. Zi coughs. It feels like the grit is stuck in my throat.

“Why is Auntie rejecting us?” Zi asks. “Mama was her sister.”

It does not make me proud to admit it, but I collapse at Auntie Phumzi’s gate, sitting right there in the dirt as though I was a chicken or goat.

“What are you doing, Khosi?” Zi’s voice rises high and shaky.

It’s been three weeks since you left us, Gogo, and we’re all alone. That is what I say to her.

But even as I wail silently, I know we’re not alone. I have this cast of characters, as my drama teacher used to say, and they follow me everywhere, commenting on everything. Just now, they stare at me in stark disapproval. Get up, stop being a child, their stares say, even while their mouths remain closed.

“I don’t know what to do, Zi,” I say. “My spirit isn’t in this fight. I just want to do what is right for Gogo. And for us, for the family. We must do the cleansing.”

Zi rattles the gate and starts to call, “Auntie! Auntie Phumzi! You must come out. We must talk to you.”

You’re letting Zi do this alone, shame, Mkhulu says finally. You mustn’t give up. Her voice is small and it doesn’t carry, it’s like a mosquito in a large room. Your voice will travel. You must just fly near your Auntie’s ear so she cannot ignore you.

You cannot give up, my girl.

That is a new voice. A woman speaking. I peer at the people surrounding Mkhulu. Who is it, speaking to me? Who is this person? I have never heard her before. They gaze back at me, unperturbed. Any one of them can speak to me, and they are multitudes. But mostly, they let Gogo or Mkhulu speak.

“What are you looking at, Khosi?” Zi has turned back from the gate, defeated.

“Oh, nothing.”

You mustn’t be like the beasts of the field, those who graze and do not even know what they are eating.

It is that same voice again.

I’m not a beast of the field, I grumble at her, whoever she is.

“What, Khosi?” Zi asks.

Did I say that out loud?

“Please, can we go home now?” she asks.

That forces me to my feet. I stand and dust the dirt from my skirt. I do not have a loud voice either. Zi and I, we are just Imbali girls, trained to be quiet. But like Mkhulu says, I can send my voice right into Auntie’s ear.

“Auntie,” I say, as though she were standing right beside us. I picture my voice flying through the air, perching on her shoulder, speaking directly into her ear. “Auntie. We are here, and we are not going home until you come out and talk to us. If we start to yell, and make a scene, your neighbors will all come out and hear how you are neglecting your sister’s children, how you are not willing to do ukugeza for your own mother. All the amadlozi are here with me, and if you think they won’t help me, you are mistaken. I am the one they chose, I am a sangoma. I can hear them just as well as you can hear me now, even though I am nowhere near you.”

“I’m here,” Auntie says suddenly.

She stands by the gate, hair wrapped in a black turban. She’s glaring at me so hard, her eyes bulge right out of her head. I want to tell her to stop staring or a bird will think her eyes are a ledge that they can land on. But I stay silent. Her husband and my cousin Beauty stand on the porch, keeping their distance.

“Speak, wena, and let us be done with it.”

“We must do this thing,” I say. “It’s time.”

“How can you do ukugeza?” Auntie protests. “You are not even wearing proper mourning clothes, hah! Are you going to burn your everyday clothes? And tell me, how will we buy a goat? Do you have so many rands that you can just go and buy one? If so, why are you not making your entire family rich, eh?”

I can’t afford a goat, it’s true, but it’s also true that I know people, namely, a whole host of amadlozi, and they are on my side. They will help me. Auntie is forgetting that.

“I will get a goat,” I say. “But you must come.”

“How will you get a goat?” she shouts. “You see, hah! You can just conjure up a goat, like that. You are a witch. We will never come to your house. We will do our own ceremony here.”

“Gogo is not here,” I say. “She doesn’t sit by your hearth in your hut. She is in my hut, at my hearth, in her own home. How can you do the cleansing here?”

But she is already gone, slamming the door behind her.

Zi and I are silent for a long time as we walk home. “How are we going to get a goat?” Zi asks finally.

I wish I knew. “You will see,” I say.

How am I going to get a goat? It is not like goats wander the streets of Imbali, looking to be slaughtered so that you can do a cleansing for a loved one. Even if we were in the rural areas, goats are valued creatures.

Zi is asleep, taking a Saturday afternoon nap. It is a hot day and she grew sleepy. I would love to crawl in beside her and join her but I am vexed with this problem. We need to do the cleansing, and if I am on my own to do it, I am on my own.

Why can’t it be a chicken, Gogo? A chicken I can find. A chicken I can buy, somehow. I can search for rands in the dirt, like a chicken pecking for food, and I can stand out on the street corners offering my services as a sangoma until enough people employ me so that I can buy a chicken.

I will tell you how to get a goat, my girl.

It is the voice of the woman again, the one who has never helped me before.

Go to the hill of the witch, she says.

I almost swear, I’m so startled. Words have power, so I keep a watch on my lips. But the witch? How could she suggest it?

I avoid the witch’s hill scrupulously since that time, three years ago, when I encountered her. She had marked me, she was waiting for the chance to drag me underground where she planned to suck me dry of my life, my powers. She wanted to turn me into her own personal zombie, a slave that worked just for her. Little Man was the one to rescue me from her strong grip. And though I know I have the ancestors’ protection now, and I think she will leave me alone, I am still afraid.

Even taxis avoid driving up that hill and past her house. Everyone knows she’s a witch…everyone knows that young men and young women have disappeared, that she has turned them into zombies, that they go deep into the earth to find gold for her…and everyone’s that scared of her. Just thinking about her makes me shiver.

Go to the witch’s house, the woman says. You will find your goat tied to her tree in the front, outside of the gate.

Who are you? I ask.

I was trained to trust the amadlozi, without question. But this advice makes me very afraid. If the witch helps me, am I indebted to her? Am I allies with her, an evil one?

But you must do what they tell you to do. If my ancestor tells me to go to the witch’s house, I must go. Otherwise, I will go crazy.

Who are you? I ask again.

She smiles at me and I realize she is one of my grandmothers, truly an ancient one, from long long ago.

Take a jar of amanzi, she says. Some of the ocean water you have blessed. It is powerful muthi. Leave it as payment for the goat.

Mkhulu, do you hear what this woman is saying?

Ehhe, he agrees but says nothing more.

But why would she help me? I argue. Because I cannot believe they are sending me to the witch, the one who tried to destroy me so long ago, before I realized I was meant to be a sangoma.

She will help because I compel her to help, the woman who is one of my grandmothers says. She has sins she must pay for.

So I go.

I thought I would avoid this side of Imbali the rest of my life. I know I am safe, at least with the amadlozi on my side, but it seems prudent to avoid your sworn enemy. Yet here I am, staggering up the hill.

It is very still up here, as if the wind itself refuses to breathe. Or as if the air is weighted with the heaviness of all the evil practiced in this place.

And it is just as my ancestor said. There is the goat, tied to the tree. The witch is nowhere in sight. I do not have to go to her house or speak to her, I can simply snatch the goat and leave.

I breathe a quiet sigh of thankfulness. That woman, eish, she truly does have sins she must pay for.

I leave the jar of amanzi—water I harvested from the Indian Ocean and then blessed with the words of the amadlozi—and I take the goat home. In the morning, I will ask Little Man to help me slaughter the goat. I will take the goat to emsamo, the place where the amadlozi sit in my healer’s hut. I will burn impepho and speak to them. Zi and I will mix its stomach guts with water and wash outside. We will burn our mourning clothes, such as they are, since Gogo told us to wear our everyday clothes. And then, the cleansing will be complete.

As for me, I will be happy to have completed this important part of releasing Gogo to that side. But otherwise, I am uneasy.

I pray that the witch uses my amanzi for good, not evil.

I pray that I have not entered an unholy alliance.