Читать книгу The Anatomical Venus - Joanna Ebenstein - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

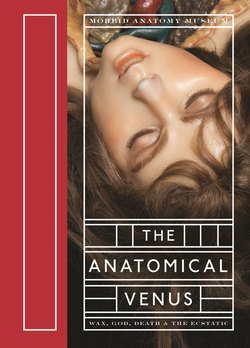

Оглавлениеfig. 10 The perfect proportions of the Venus de’ Medici, a marble sculpture created in the first century bCe, were essential viewing on the Grand Tour. In the eighteenth century, she still bore remains of red on her lips and gold-leaf on her hair. These were rubbed away during restoration in 1815. (28) approaches, including what we would today define as science, aesthetics, and metaphysics, and which attempted to understand a divinely created natural world. The Wunderkammer, an expression of this worldview, was organized not by scientific principles as we now understand them, but as a microcosm of the universe intended to encourage the beholder to marvel at the wonder of God’s works. At this time of unprecedented global exploration, marvels abounded, as European voyages of discovery returned with shiploads of new species, arte facts, and stories from previously unimagined or little-known civilizations. Leopold II appointed his court physician and natural philosopher Felice Fontana (1730–1805) to oversee the creation of his new museum; he remained director of La Specola until his death. Inspired by the famous anatomical wax museum in Bologna that had been established some thirty years earlier, Fontana fig. 10 fig. 11 fig. 11 Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1482–85), commissioned by the Medici family, was a must-see on the Grand Tour. employed one of its sculptors, Giuseppe Ferrini (d. 1815), as artistic leader of his own dedicated in-house workshop for the creation of wax models. Fontana’s grand and ambitious aim was to create an encyclopaedia of the human body in wax—one that would render human anatomy accessible and understandable to the general public, instructing people in scientific principles and the divine architecture of the human body. Fontana hoped that it would end the need for cadavers in the teaching of anatomy: If we succeeded in reproducing in wax all the marvels of our animal machine, we would no longer need to conduct dissections, and students, physicians, surgeons, and artists would be able to find their desired models in a permanent, odour-free, and incorruptible state. The wax models produced by the workshop at La Specola were posed as if alive, healthy, and pain-free, in an attempt to distance the study of anatomy from the contemplation of death and bloody internal organs. The Anatomical Venus was further removed from notions of death and the corpse as she drew AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 28 12/01/2016 12:14 chapter one[1]