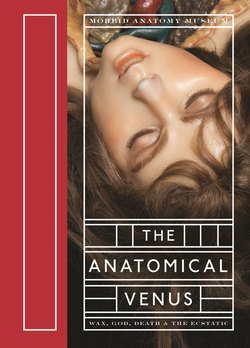

Читать книгу The Anatomical Venus - Joanna Ebenstein - Страница 34

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление(37) accuracy, and are suggestive rather than descriptive. Female figures contain, in addition to their other rough-hewn organs, a tiny fetus, sometimes attached to the body by a red silk thread. These enigmatic and seductive toys may have been tools for teaching expectant mothers or midwives about childbirth. Or they might, as many scholars believe, have been more decorative in nature, intended as collectables for Wunderkammern, or as a way for physicians to adver tise their professional standing. The first full-sized female instructional anatomical wax models began to be created in the early eighteenth century. In 1719, French surgeon and anatomist Guillaume Desnoues (1650–1735) (see also pages 96, 97, 100–101) publicly exhib ited a dissectible wax woman featuring a newborn child with the umbilical cord fig. 19 Engraving of Pieter Pauw, who instigated the building of Leiden’s anatomical theatre, performing an anatomical dissection there (1615). The skeleton holds a banner reading ‘Mors ultima linea rerum’ (‘Death is everything’s final limit’). fig. 20 fig. 21 fig. 22 still attached. Little more than a decade later, in London, Paris-trained anato mist and modeller Abraham Chovet (1704–90) exhibited a female depicted as though in the painful process of being vivisected. The figure was represented as ‘...a woman big with child chained upon a table; supposed to be opened alive. In the face there is a lively display of the agonies of a dying person, the whole body heaving and the hands clinched, the action suitable to the character of the subject.’ (General Evening Post, 1734). The circulation of her blood was dem onstrated by a network of blown-glass tubes coursing with blood-red claret. In France, Marie-Catherine Biheron (1719–86), an artist with experience of the dis section room, had, from the age of sixteen, created wax anatomical models that she exhibited to the public on Wednesdays for three francs per person. Biheron later displayed her pieces in London, where they were reportedly admired by the famous Scottish surgeons John and William Hunter, and eventually pur chased by Empress Catherine II (1729–96). In late-eighteenth-century Vienna, court sculptor Josef Müller-Deym (1752–1804) displayed a dissectible female wax model of a pregnant woman. Müller-Deym also made other kinds of wax ladies: fig. 20 Detail of the female reproductive system, from Andreas Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543). figs 21, 22 Idealized female nudes, from Bernhardus Siegfried Albinus’s Tables of the Skeleton and Muscles of the Human Body (1749). oVerleaF Hand-coloured woodcut frontispiece of Andreas Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica, Libri Septem (1543). AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 37 12/01/2016 12:14 THE BIRTH OF THE anaTOmIcal VEnUS[1]