Читать книгу The Anatomical Venus - Joanna Ebenstein - Страница 27

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

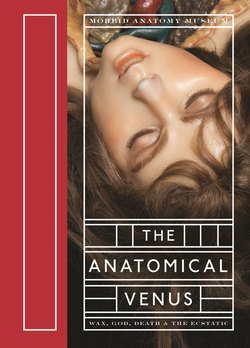

Оглавление(29) on the historical and artistic figure of the Roman goddess of love, beauty, and fertility, evoking a long history of paintings and sculptures of placid, idealized nudes. In fact, each pristine wax model at the museum was the product of the careful study of cadavers that were delivered from the nearby Santa Maria Nuova hospital. Although the collection fell short of its ambition to render all further human dissection unnecessary, today, over two hundred years after their creation, La Specola’s waxworks are still considered remarkably accurate, some of them demonstrating anatomical structures that had yet to be named or described at the time of their making. The best known of all the wax artists, or ceroplasticians, employed at La Specola’s workshop was Clemente Susini, who had trained as an artist and went on to teach at Florence’s Academy offine Arts. Susini began as Ferrini’s assistant fig. 12 Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538) was commissioned by the Duke of Urbino as a gift for his young wife, Giulia Varano; it represents an allegory of marriage, and wifely duties of eroticism, fidelity, and motherhood. fig. 12 fig. 13 in 1773, was promoted to lead modeller in 1782, and worked at the museum until his death, when he was succeeded by his assistant. It was under Susini’s over sight that the museum created its finest and most iconic works, among them the ingenious, dissectible Medici Venus. The figure of Venus was no random allusion; by the eighteenth century she had a long-standing relationship with Florence. As Rebecca Messbarger explains, the city had been nicknamed ‘Venus-Fiorenza’ in the sixteenth century to symbolize the fertility, happiness, and beauty offlorence under Medici rule. Depictions of Venus were also, Messbarger notes, a ‘principal organizing theme’ on the Grand Tour, a secular pilgrimage made by scores of wealthy and well- educated young European men, and occasionally women, to acquaint themselves with the artistic achievements of continental Europe. Italy’s treasures loomed large in the Grand Tour, with Florence and its Venuses high on the list: Grand Tourists would visit Botticelli’s iconic Birth of Venus (1482–85) in the Medici country villa, then stop off at the royal gallery of the Uffizi to pay homage to Titian’s sensual Venus of Urbino (1538) and the Venus de’ Medici, a Hellenistic sculp ture and exemplar of perfect female proportions created in the first century bCe. fig. 13 Detail of Johann Joseph Zoffany’s The Tribuna of the Uffizi (1772–77), depicting Grand Tourists paying homage to the much lauded artworks of the Uffizi Gallery. Titian’s Venus of Urbino and the Venus de’ Medici are prominently displayed. AV_00966_pre-pdf layout_001_215.indd 29 12/01/2016 12:14 THE BIRTH OF THE anaTOmIcal VEnUS[1]