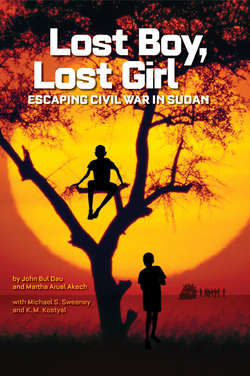

Читать книгу Lost Boy, Lost Girl: Escaping Civil War in Sudan - John Dau Bul - Страница 11

John

ОглавлениеWar came to my homeland when I was thirteen years old. We had been expecting it, but nevertheless it came as a shock when my village was actually attacked.

The Dinka had heard omens of war for a long time. Many people still believed in spirits that lived in animals and plants, and these spirits spoke to them about the coming of a very bad time. My parents told me one story just as they had heard it. They said a tortoise spoke to a man on a path outside the town of Bor. Among the Dinka, the tortoise is believed to be very smart. The tortoise told the man, “I am sent by the Lord. I bring you news of doom. Your country, Southern Sudan, will be destroyed.” The tortoise said the Lord meant to punish the people of Southern Sudan for being unfaithful, and it gave the man three choices. “One is drought,” said the tortoise, “and if you choose it, I will punish you by withholding the rain. If you do not choose that, I will punish you with flood. And if you do not choose that, I will punish you with war. Now, you must choose.” The man was frightened and ran away. The tortoise yelled at him, saying, “You must answer me! You must choose!” So the man chose war.

The man told everyone what the tortoise had said. The people of Duk Payuel, the village where my family was living at the time, debated whether the man had made a wise choice. Some argued in favor of drought. They knew they could survive because the Dinka have weathered many a dry spell. But drought meant famine, which would hit the women and children the hardest, so the villagers rejected that choice. Some argued in favor of flood. They knew the Dinka could survive because they could catch fish as the swamps filled with water. But floods meant our precious cows would die, so the villagers rejected that choice too. Most of the people in my village finally decided that the man had chosen wisely, but everyone kept talking about what the tortoise had said.

A month or two later, a crow landed on the shoulder of an old woman who was sitting making rope in the shade of her house. The crow gave her the same choice: drought, flood, or war. The woman didn’t know what to do, so she said nothing. The crow flew away.

Then a prophet had a vision. This man, named Ngun Deng, lived among the Nuer, a neighboring tribe. He saw bad things in the future. War would come to Southern Sudan, he said, and many would die. In the end, Southern Sudan would defeat the enemy, but it also would suffer defeat. Then he spoke a final prophecy: “Yours will be a generation of black hair.” The elders in my village debated his meaning. They decided he meant that the oldest and youngest would die. The oldest had gray or white hair, and the youngest had little or no hair. Only the black-haired young people would live, and they would see many troubles.

It was such a terrible time. People believed the words of the tortoise, the crow, and the prophet. Then one day the sun glowed blood red. My mother said it meant that blood would flow. “People will fight, and there will be lots of killing,” she told me.

At the time, I did not know much about my country’s history. Anyone who studied the early years of Sudan might have seen civil war in its future. Britain granted Sudan independence in 1956. The new nation brought together groups of people who had little in common. Arabs who practiced Islam and spoke Arabic dominated the northern half of Sudan and the capital, Khartoum. Black-skinned tribes who were either Christian or practiced traditional religions and who spoke dozens of languages dominated the southern half. At first, southern citizens saw little change in their daily lives while living in their new country. In the early 1980s, however, when the national government, dominated by northern Arabs, tried to impose Islamic laws on the entire nation, civil war broke out. Northern soldiers stormed into southern villages to quell the violence, but the fighting raged on. The northern armies got the best of most battles because they had more soldiers and guns and all of the airplanes. Those armies drew near shortly after we heard the prophecies of war.

I remember the night the soldiers came to Duk Payuel as if it were yesterday. The first sound I heard seemed like a low whine or whistle. It rose from far away on a moonless evening as I tried to sleep on the floor of a hut. About a dozen boys and girls shared the hut with me on that hot and sticky summer night in 1987. As government soldiers shelled and burned the countryside and airplanes strafed and bombed the villages, refugees moved south. Some came to Duk Payuel, and that is how I came to share a hut with strangers. My parents and other adults slept on the ground outside.

I was having trouble sleeping, so I heard clearly the whine or whistle as it grew louder. Then I heard more sounds just like the first. A chorus of shrieks descended toward our village.

Boom! Boom! Boom! Explosions shook the earth. I heard a huge crackling sound like some giant tree being splintered in the forest. I had learned enough from the elders who had gathered in our village to realize what was happening. Duk Payuel was being shelled by invaders.

I stood up and tried to run, but it was so dark in the hut that I could only stumble about. Other children were running too, and we smacked into each other and into the walls and support beams. Outside, amid a new sound that I recognized as bursts of gunfire, my mother shrieked the names of her children. I managed to find my way outdoors and looked up to see the red glare of fire dancing atop the trees of the forest and the roofs of our village. Everywhere, people were running in a mad panic. Bullets tore through the village, making angry zipping sounds like bees.

I looked for my parents and my brothers and sisters, but I saw no family members. I started to panic. Where should I go to be safe? Thank goodness, just then I thought I saw my father running in front of me. He disappeared down a path through the tall grass, and I followed him. I ran and ran but did not see him. Suddenly a hand reached out from the thick grass at the side of the path and grabbed my shoulder. As I felt myself being pulled into the grass, I heard a hoarse whisper.

“Quiet, quiet, quiet,” it said.

Nine northern soldiers dressed in dark clothes ran along the path I had just left, passing inches from my face without seeing me. They fired their guns as they went. The two of us backed deeper into the grass. We did not say anything, just crouched and waited for daybreak.

When it came, I was shocked. The soldiers had gone. My village was destroyed. I could see smoking ruins of huts and luaks, dead animals, and bodies of villagers whom the adults were trying to hide from the eyes of children. And I could see by the early morning light that the man who had saved me was not my father. He was Abraham, a neighbor. My family was missing, and I felt certain they had been killed or taken prisoner.

Abraham said we would have to flee if we wanted to stay alive. The soldiers from the north would probably kill us if they found us. Our best chance for survival lay in finding somewhere the soldiers could not hurt us. I did not know how tough our journey would be, but I knew we did not have much in our favor. We had no food or water. I wore what I had worn to bed, which is to say I was naked. As we fled we might encounter more soldiers, not to mention deserts and jungles and the dangers that lurk there.

Abraham and I ran toward the east and the rising sun. We kept to the paths that serve as roads in Southern Sudan. Every time we heard approaching feet we ducked into the brush. When the noise passed by, we emerged and started running again. For a while we traveled with three other refugees from the invading army, a Dinka woman and her two daughters. We had nothing to eat for a long time until Abraham found a pumpkin and an amochro, a short plant with a fleshy, juicy root shaped like an onion. The girls complained of being tired from walking so much, and I was very tired too. My bare feet bled, and my stomach growled after the food ran out. But we kept going toward the east.

One day, as Abraham was leading us single-file along the path, he disappeared around a curve. When we caught up to him, we saw he had stopped near a group of soldiers carrying assault rifles. Abraham was wearing a nice shirt, and the men ordered him to give it up. When Abraham hesitated, the men pummeled him with sticks and the butts of their rifles until he took off the shirt and offered it to the officer in charge. The soldiers beat the woman too. I wanted to cry out, but I thought it best to stay silent. Then one of the soldiers grabbed a clump of my hair and twisted. Tears came to my eyes, but I willed myself not to cry out. The man tore a clump of my hair out by the roots and threw it in my face. That seemed to satisfy him, and he stopped picking on me. We lay in pain by the path and said nothing. Eventually the soldiers got tired of torturing us and moved on.

We saw other people from time to time. One group of soldiers beat Abraham until he almost died, and also punched me and hit me with sticks. They took the woman and her two daughters with them when they left. We never saw them again. It took a long time to recover from this vicious beating, but Abraham and I grew strong enough to walk again. I remember those days as a blur. We did nothing but walk like zombies, stumbling along and searching for food. All the while we headed east. I wanted to quit, but Abraham insisted we could not stop.

“We will keep going until we are killed,” Abraham said.

I learned then that we had a destination: Ethiopia. It was a separate country east of Sudan. We would have to walk about five hundred miles to reach its border. Frankly, I did not believe we would make it. Every morning when I awoke hungry and sore, I thought it might be the day I would die. Facing the threat of starvation, thirst, and murderous soldiers, I looked upon our long walk as a sort of grim game. The object was to see how far we could get before we died. I prayed I would live long enough to learn what had happened to my family.

As we walked, Abraham told me stories. He taught me how to find a kind of grass called apai and how to chew its sweet stems for food. He taught me to beware of water holes because they attract animals and people. And he taught me the best ways to hide. This last lesson came in handy when a group of soldiers nearly found us along a riverbank. We had stopped at a big river covered with apai. Abraham and I had picked our apai and submerged our bodies comfortably in the water as we chewed.

Only a minute or two after we settled in, I heard voices speaking in Arabic, along with gunshots and laughter. I was very scared, but I kept still and hid amid the apai. I grabbed some roots on the bottom of the river and pulled myself slowly down until only my lips and nose were above water. Abraham did exactly the same thing. We breathed as quietly as we could and watched the men through the muddy water that covered our eyes.

A squad of Arabs stood on the bank a few yards from where I hid. They fired their guns in the air in their joy at having found water, and they shouted “Allah akbar!” which means “God is great!” Some sat and smoked tobacco. Some prayed. One man urinated in the water not far from me. Some even jumped in the water and splashed about. The waves they made rocked me as I tried to stay hidden.

After an hour or so, an officer blew a whistle and everyone jumped to attention. Then they marched past us and went on their way. Thus ended the longest hour of my life. When I felt sure they were gone, I emerged from the water. Abraham came out too. We ran into the forest, where we felt temporarily safe. When we had calmed down, we started walking again.

In the following weeks, we met other refugees. It became clear that lots of people were fleeing the war by walking to Ethiopia. Many died from gunshots, thirst, and hunger, but Abraham and I continued on. We met fifteen boys and two adults along the way, and we all decided to walk together.

By the end of October, the land was getting to be very dry. We had nothing to drink. Some of the boys said they wanted to die. Some tried to cry, but no tears came. We were so thirsty that we ate mud to force some moisture into our mouths, but it did not really help. I was so afraid I would die that I gladly drank urine to stay alive. I sang to try to keep my spirits up, but it did not help much. “Don’t let your heart get upset,” I sang to myself. “You are in the hand of God.”

The group that joined us began to dwindle away. Some died of thirst and hunger, and the two adults were shot when we ran into an ambush. Finally, only Abraham and I and two of the other boys remained. We kept walking with nothing to eat or drink. But at the moment of my greatest despair, we found hope. Abraham disappeared ahead of us. When he returned, he brought water in his cupped hands. I drank and knew I would survive. Right around the corner was the huge Kangen Swamp. We caught and cooked some turtles and ate their flesh and their eggs. I drank muddy swamp water. It tasted great.

Not long after that we came to the border of Ethiopia. Members of a friendly tribe on the Sudanese side gave us a blanket, some elephant meat, and some advice. They told us to cross into Ethiopia and head for a refugee camp called Pinyudu. So that is where we went.