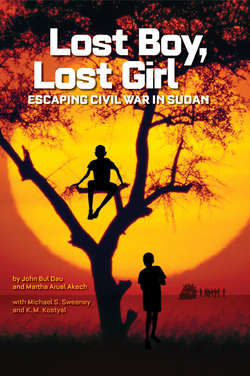

Читать книгу Lost Boy, Lost Girl: Escaping Civil War in Sudan - John Dau Bul - Страница 9

Martha

ОглавлениеI didn’t grow up in the countryside, the way John did. I grew up in Juba, the most important city in Southern Sudan. My family—my father, my mother, my little sister, Tabitha, and I—lived in a compound with another family. Our house had a roof made of dried, thatched grasses and three rooms—a kitchen and two small rooms where we slept and, during the long rainy season, where we played. During the hot, dry season, everybody would bring chairs outside and sit in the shade. Despite the sweltering heat of the Equator, Sudanese people spend most of their time outdoors when it’s not raining.

On dry season evenings, when it was cooler, all of us children in the neighborhood would gather together to play tag. Sometimes we girls pretended that we were cooking, and we’d make plates and cooking pots out of clay, the way Sudanese women do. Or we played with dolls our mothers had made us out of scraps of old clothing.

My father was a policeman, but early in the morning before he went to work and before the scorching sun was very high in the sky, he and my mother would take Tabitha and me with them while they worked in a garden they had not far from our house. They grew mostly groundnuts. You call them peanuts, and we eat them just the way you do, as snacks or in peanut butter, which we also put in sauces or in our porridge.

Juba was a major port city on the great Nile. The longest river in the world, the Nile flows through the length of Sudan, then through Egypt to the Mediterranean Sea. Large boats heading south on the Nile couldn’t go any farther than Juba because of the rapids and shallows on the upper part of the river, so that made my town a busy port. Still, most of the roads in town were unpaved, and in the dry season, the dust kicked up by cattle being herded through town or by farm carts loaded with vegetables swirled through the air. In the rainy season, the roads were a muddy mess. The main paved road in town had been put in by the British when Sudan was a colony of theirs.

Sudan is the largest country in Africa, and there are hundreds of groups, or tribes, and many languages spoken throughout it. Like John, I am part of the Dinka people, the biggest tribe in Southern Sudan. Besides my tribe, I also belong to a clan. This is like a large, extended family whose members help one another. If you are Dinka, your clan is very important to your identity. John’s clan is the Bor Nyarweng. Mine is the Abek. My Dinka first name is Arual, the name my father’s family gives to firstborn girls.

My parents were Christians, and on Sundays we went to church. Before Christianity came to Southern Sudan, people there believed in witches, and they thought that illnesses came from being cursed or bewitched. Those beliefs still lingered when I was a child, even in cities like Juba.

Once, when my younger sister, Tabitha, was quite little, she got very sick. We could see where each bone in her body was connected because she was so thin. Friends of my mother’s said that her baby had been cursed. They told my mother that she needed to find a witch doctor to get rid of the curse. At first, she said, “No, I’m a Christian. I don’t believe in those things.” But when Tabitha got worse, my mother became frantic and gave in. She found a witch doctor who came and looked at poor little Tabitha.

“Someone has put magical bones on her body, and they’re killing her,” he pronounced. He said that only he could see the magical bones and only he could get them off. So my mother, in her desperation, hired him. But every time he came, he would leave Tabitha in her sick bed and walk around outside our compound.

Now in Juba there were no trash collectors, so people threw their trash outside the fences that surrounded their homes. When the witch doctor walked around outside, he would come back and lean over Tabitha and suddenly pull some kind of bone away from her. To my mother, those bones looked suspiciously like garbage people had thrown away. “Go away, and don’t come back,” she told him. Instead she prayed that God would heal her baby, and after some time, Tabitha recovered.

I was a little child then, too little to understand how sick my sister was. Also, like all small children, I thought my parents would always keep us safe. Most of what I remember from my first five years in Juba was the happy sound of people in my family and neighborhood. My parents loved me, and every night when I crawled into my nice metal bed with the comfortable mattress on it, the world seemed like a good place.

I didn’t understand that Southern Sudan had been a dangerous place for decades. When my parents were children, there had been a war between the southerners and the Arab Muslims who dominated the government in Sudan. That war ended with a treaty, and for ten years peace had kept life calm and allowed people to settle and prosper. But trouble started brewing again just after I was born.

The southern people were angry with the Arab government about a number of things. One was that the government planned to build a canal into the great swamp called the Sudd. The canal would carry the water away from the south to the Arab Muslims in the north and on to Egypt. Also, prices of critical supplies such as oil, bread, and sugar had risen because of the policies of the government in the capital city of Khartoum. Most important, the government had imposed Muslim law on the whole country, even though we black Africans of the south weren’t Muslim. The Arabs had never had much respect for us. They treated us as if we were beneath them, as if we were their servants.

In Juba and in other cities students protested against the government, and some were killed in the riots. Men in the south who were fed up with policies that favored the north formed the Sudan People’s Liberation Army, and fighting flared in the countryside between the SPLA, as we called that army, and local militia groups that the government had backed. But I wasn’t paying attention to any of that. I was just a girl of five, playing with my sister and my friends, expecting life to go on the way it was forever.