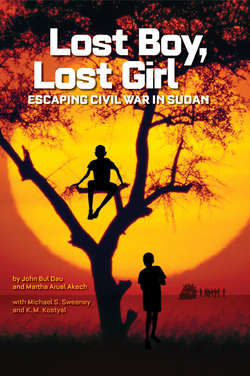

Читать книгу Lost Boy, Lost Girl: Escaping Civil War in Sudan - John Dau Bul - Страница 12

Martha

ОглавлениеI was a little girl, not even six years old, when the happy days with my family in Juba disappeared forever. It all started when my mother and my little sister and I left our home and went to stay with my grandmother and my aunt’s family. They lived in a farming and cattle-raising village in the countryside. But it wasn’t really my home, and I got scared when my mother left us there and went back to Juba. When she returned to us, she brought a lot of our belongings with her—things like clothes and cooking pots and utensils.

When you are little and in the arms of your family, you don’t really understand, or even care, what’s going on in the rest of the world. Now I know, though, that my parents moved us away from Juba because war had broken out in Southern Sudan, and everyone expected that Juba would become the scene of fierce fighting between government-backed troops and the SPLA.

By Dinka custom, families move to places where the father has relatives. That meant we couldn’t stay with my mother’s mother and sister for very long. So we moved again, this time to a village called Wernyol, where my father had been born. A little later he joined us there.

We stayed in my uncle’s house there for a few months because we had no house of our own anymore. Then my father’s relatives held a feast and killed a cow to roast and invited a lot of people to come and enjoy the meat and help us build a new house. As the delicious smell of meat cooking drifted through the air, everybody worked together, and soon we had a small house with mud walls and a thatched roof and a garden for vegetables nearby. My family was all together again and we had our own home, so it seemed that all was well.

We discovered that life in the country was different from life in the city. We had to keep all our food safe from rats and mice and cats, so the women wove grass baskets for storage. Or they would cut the top off a big gourd they had grown and use that, sticking an ear of corn in the opening to seal it. There are some gourds that grow perfectly round, and we would cut these in half and use them as plates. Other gourds we used as drinking cups. People carved spoons from wood, or we collected empty snail shells, which make really good spoons. Cooking pots were made out of clay and shaped by hand. All the women knew how to do this, but some people were so good at it that they could sell their pots. Not for money—there was no money. Instead they might get a big container of corn or a cow.

My mother had given Tabitha a metal spoon, a leftover from our life in Juba. Tabitha treasured that spoon and always hid it inside the luak, the cattle shed, under a log that supported the wall. One day, when it was time to eat, she went to get it, and when she reached under the log, a snake bit her! She was screaming and screaming. We watched that big long snake slither away, but luckily it wasn’t poisonous. We always had to be careful about snakes in the countryside. There were lots of them. We even saw a mad cobra in the yard. It was rearing up, taller than we were. We ran and ran, as far from it as we could get.

One afternoon, my parents went to church in a nearby village and left Tabitha and me behind with my father’s cousin, a woman named Nyanriak. It was a nice, quiet afternoon, with cattle grazing in front of the family compound and Nyanriak in the yard grinding millet—a kind of grain we Dinka eat a lot. We were playing with other kids in the sunshine when all of a sudden we heard gunfire, and Nyanriak yelled at us, “You children, come here, come here!” We went running toward her and she pushed us toward the luak. We were screaming, “The Murle are coming. The Murle are coming.”

The Murle are another tribe in Southern Sudan, and we knew about them because they would raid villages and steal not only cattle but Dinka children, whom they would raise as their own. It was said they couldn’t have children themselves, and that’s why they did this. Whenever a village heard gunfire, the first thought in everyone’s mind was that the Murle had come on a raid. But the Murle don’t burn villages down, and now houses were on fire, and the world had become a big storm of smoke and gunfire and screaming. People were running toward us, shouting out the names of their children or shouting at us to “Run! Run!”

Nyanriak grabbed us and her five small children and herded us along with the crowd, prodding us to run as fast as our short legs would carry us. We raced after the other people leaving the village, running through tall grass high above our heads. The people ahead of us had made a path in the grass with their running, so we followed that, but sometimes we had to scramble through thorny bushes that scratched as we passed. We were barefoot, the way most Sudanese children are, and our feet grew big blisters on them, but we kept going as fast as we could. I was holding Tabitha’s hand the whole time. She was only three and not much of a runner. But then neither was I.