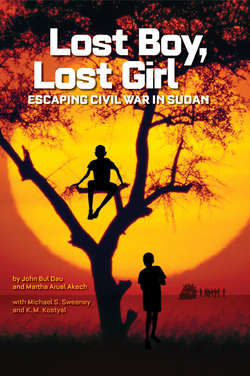

Читать книгу Lost Boy, Lost Girl: Escaping Civil War in Sudan - John Dau Bul - Страница 8

John

ОглавлениеWhen I was a young boy, my great-uncle Aleer-Manguak was killed while trying to protect our cattle from a lion. His bravery made me proud.

My people, the Dinka, raise cows in Southern Sudan. We like to drink their milk, and we use them as a form of money. Protecting our precious cows from predators is a constant problem. Sometimes we must kill or be killed.

One day five lions sneaked into the pastures near Paguith, my first village. Lions are smart and work in groups. If they want to attack a herd, they first try to make the cows panic. They sometimes do this by creeping near the cattle and spreading their urine on the ground. Then they quietly move to the opposite side of the herd. When the cows wander far enough to sniff the odor of lion urine, they know a killer is nearby and run in the opposite direction—right toward the waiting lions. This is exactly what happened that day. Hundreds of cows ran into the trap, and two fell to the lions’ fangs and claws. My brother and some other Dinka boys saw what happened and tried to chase the lions away. They ran at the lions and threw sticks to drive them from their kill. That just made the lions angry. Some of them turned on the boys, and they had to run for their lives.

The boys hurried to the village and alerted everyone that lions had attacked the cattle. The women of the village began to shout, and the men began to arm themselves. My father and great-uncle got their knives and spears and left their houses to meet the other men of the village. They quickly decided to form a hunting party. They would have gone after the lions right then, but night had begun to fall and they had to suspend their pursuit. Everyone went to bed anxious for the hunt to begin. After the sun rose the next morning, a hunting party that had special skills in tracking lions began to follow their path. About thirty men, all armed with spears, set off after the trackers through the tall grass.

By the time they found the lions, two had run off, but three remained in the thick grass and brush. The hunters circled them and began to walk toward each other, drawing the circle smaller and smaller. Two of the three lions didn’t want anything to do with the Dinka hunters and escaped through gaps in the circle. That left one. He was a big male with a broad face and a golden mane.

Remember how I said lions are smart? This one certainly was. He did not want to tangle with humans and was trying to keep his distance, but the shrinking circle gave him no chance to flee. The lion began to get nervous. To get close enough to actually kill the lion, the hunters needed to create a distraction. The Dinka say, “Who is going to bring the lion?” It is a special kind of job. The bringer stabs the lion to make it angry. The lion then chases its attacker, who runs for his life. The fastest runners in the village train to “bring the lion.” My great-uncle was one of them.

As the men of my village knelt with their spears pointed at the center of the circle, Aleer-Manguak and another runner rushed straight at the lion. As they sped by, they stabbed the great beast with the tips of their spears. The lion roared in anger and pain. It rose on all four legs and chased Aleer-Manguak. The beast caught him just as he reached the circle of hunters. It swiped at him with one paw, tearing open his shoulder and breaking his ribs. The other hunters swarmed over the lion and pierced its flesh with their spears, killing it quickly. My great-uncle lived just a little while longer, and then he died too.

The entire village honored my great-uncle. The hunters took the lion’s body and cut off the tail, paws, and mane. They gave these to Aleer-Manguak’s family as tokens of respect for his brave deed and his self-sacrifice. The family hung the prizes in their luak, a round Dinka cattle pen with a thatched roof.

Even as a boy of seven or eight, I knew why everyone honored Aleer-Manguak in death. Almost from birth, a child is taught the values of the Dinka, which my great-uncle had in abundance. These values include respect, courage, hard work, and self-sacrifice. A Dinka child is also taught to fight for family, village, tribe, and country. The strongest fighters are those who keep two rules. First, they never, ever give up, no matter what the odds are against them. And second, like the lions, they work together. A Dinka man who follows these rules and maintains the values he learned as a boy can grow up to be a great leader, like my great-uncle. At the time I had no idea how much I would have to live by these rules just to survive the ordeals of my life. Aside from the occasional marauding visit by a lion or hyena, my childhood years were peaceful and fun.

Nobody kept exact records in Southern Sudan, but my family believes that I was born in July 1974. My father was Deng Leek Deng Aleer. He had been a mighty wrestler when he was young and later became a judge. He did not go to school to learn the law. Instead, we Dinka say that he held the laws in his heart. He knew our traditions and our values and was called upon to settle disputes. He disciplined me severely when I was young, especially if I showed any disrespect. At the time I thought he was too strict, but now I realize that he was raising me to be strong, as a Dinka man should be.

My mother was Anon Manyok Duot Lual. She was the daughter of a Dinka chief and was considered quite an excellent bride. My father had to pay many cows to her male relatives as a sign of his respect before he could marry her and give their children his name. It is common among the Dinka for a man to have more than one wife. After my father married my mother, he took three more wives, and he had many children. I am the youngest son of my mother.

Like all good Dinka, my family raised cattle. These are not the cows you see on North American farms. Dinka cows look wilder than their American cousins and have thick horns that are two to three feet long. Their milk is sweet, and we drink it all the time. We slaughter a cow for its meat only to mark a big occasion. We believe that cows are a gift from God.

Our legends say that God offered the first Dinka man a choice between the gift of the first cow and a secret gift, called the “What.” God told the first man to carefully consider his choice. The secret gift was very great, God said, but he would not reveal anything more about it. The first man looked at the cow and thought it was a very good gift. “If you insist on having the cow, then I advise you to taste her milk before you decide,” God said. The first man tried the milk and liked it. He considered the choice and picked the cow. He never saw the secret gift. God gave that gift to others.

The Dinka believe that the secret gift went to the people of the West. It helped them invent and explore and build and become strong. Meanwhile, the Dinka never built factories or highways or cars or planes. They were content to be farmers and cattle raisers. They lived happily for centuries, drinking milk and using cows as currency. Cows remain the lifeblood of the Dinka culture.

Narrow dirt paths link one village with another all over Southern Sudan. There are no paved roads and virtually no buildings of metal or brick. Mud, sticks, leaves, and grass are our construction materials. There are no phones, no computers, no cars, no kitchen appliances—virtually none of the conveniences that many people in the world take for granted. Our culture has not changed much in hundreds of years, and we like it that way.

Southern Sudan is very flat. The land is covered with grass that grows eight feet high between patches of forest and farmland. The year follows seasons of rain and drought. When it rains, the flat lands fill with standing water and our villages become like swamps. When the rains stop, the land dries to dust and the sun burns very, very hot. Some lands—in an area called the Sudd that separates Northern and Southern Sudan—never go dry. Even late in the dry season, these lands hold enough water to grow grasses to feed our cattle. Beyond those swampy lands is the White Nile River. It has crocodiles, mosquitoes, and hippopotamuses. For many centuries, the swamp and the dangerous animals that live in it served as a barrier to people who wanted to explore Southern Sudan. That’s why the Dinka lived in isolation until the nineteenth century, when British explorers and missionaries began pushing through the swamp.

My father’s father’s brother was a great man. His name was Deng Malual Aleer. He was a big chief in Southern Sudan and fought on the side of the British colonizers against the Arabs who lived in Northern Sudan and wanted to control the whole country. He gave permission for missionaries to do their work in the southernmost part of Sudan, and that is how my family became Christians. Because of Dinka traditions and the work of the missionaries, I have two names. My traditional Dinka name is Dhieu-Deng Leek (pronounced “Lake”). I also am known by my Christian name, John Bul Dau. Many Dinka families give their children a name from the Bible when they are baptized, and that is how I became John at age four or five.

Like all Dinka children, I had to do chores from a very early age. I got up when the red circle of the sun cleared the horizon. Every morning, I went immediately to our luak with my brothers to lead our cows outside. When the luak was empty, we cleaned the floor. We gathered up the dung from the night before and hauled it outside. Then we broke it into tiny bits to dry in the sun. We burned the dried dung every day. It gave off a smelly smoke that protected our cows from biting flies and other pests.

Meanwhile, my father and mother tended to their garden, cutting weeds from their patches of corn, beans, sorghum, and pumpkins. Mother took a break around midday to make a lunch of thin griddle cakes. The older boys kept watch over the cattle, while my friends and I played with our toys. We did not have fancy playthings that make noise when you push a button. We made toy cows out of clay and made the sounds of cows and goats with our mouths. We had fun pretending to run our own farms. We also played a running game called alueth. It’s played with two bases, one for someone taking the role of a lion and the other for children whom the lion “hunts.” The children leave one base and run toward the safety of the other. If the lion catches a child between the bases, he joins the lion’s team. As more and more children become “lions,” it gets harder and harder for the remaining children to avoid getting captured.

Once I was old enough, I went with the older boys to protect the cattle as they grazed on the thick grasses around our village. Like the other boys, I learned how to fight with knives and spears and clubs. I wrestled with my friends until I grew strong and tall. My friends and I prided ourselves on learning how to throw one another to the ground and on mastering the many moves of a champion wrestler.

I didn’t go to school. The only schools were in the biggest of villages, far away, or in the northern part of Sudan, where people spoke Arabic. Instead, I learned what I needed to know through the rituals of storytelling. Everyone played games with riddles, shared stories among the family after dinner at the end of the day, and told stories at cattle camp, a grassy place away from home where villagers tended their precious cows. Our stories and riddles not only taught us about the animals and plants and people of our world, but they also bathed us in lessons of right and wrong. When we heard stories about hyena, for example, we learned how his greedy, self-centered ways caused him many problems. We learned that we wanted to be more like the noble eagle, the smart fox, and the powerful elephant.

Every night my brothers and sisters and I told each other tales we had heard during the day, and we begged our parents to share with us the older stories from when people and animals lived together and spoke to one another. Then my mother checked to be sure the doors and windows had been sealed against the clouds of mosquitoes outside, and we lay on our beds of cowhide. Our village had no electricity, and our daytime cooking fires burned too low at night to give off any light, so each night brought nearly total darkness to the inside of our house and luak. Night after night I drifted off to sleep, never dreaming how soon our beautiful storytelling evenings would end.