Читать книгу Mingus Speaks - John Goodman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

“Don’t take me for no avant-garde, ready-born doctor.”

Many people have tried to explain Mingus to the world. Finally, it’s time for him to do the talking.

His music has been praised, anatomized, criticized, discographized. No longer jazz’s angry man, he has achieved prominence as one of the great jazz composers, largely through the efforts of his wife Sue, who has done so much since his death to keep three bands going and let the public hear his music. Mingus is in the composer pantheon with Duke Ellington and a very few others. Wynton Marsalis loves him; he’s part of the received jazz canon. Would he be proud of that? Dismissive? Both, probably.

For many critics and listeners, his music has been hard to fathom: is it traditional, free, or what? And yet, recent remarks of younger people in blogs, coming to his music for the first time, are revealing. (He always knew the kids would respond.) In The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady, one person heard “images of creeping hobos, fawning sophisticates, domestic loneliness, and a mind on fire.” On YouTube, the audio track of “Solo Dancer” from Black Saint elicited this, among many comments: “So i’m 15 and this is the first time i heard this song AND IT’S FUCKING BRILLIANT. Can someone point me to a good place to start with Charles Mingus? Please?”1

His music is among the most personal of expressions in jazz. Filled with recurring recombinations of source material of all kinds (gospel, Dixieland, concert music, Spanish and Latin music, bebop, swing, New Orleans, R&B, free jazz, circus, and minstrel music), each piece is also a unique minibiography in sound. Not every one is fully realized, but each piece tells something about where Mingus has been. These are not generally Monkish or modernist-style compositions. They are personal statements.

For a man as verbal as Mingus was, a great frustration seemed to be his constant need to explain himself—in his music, to his audiences, in his book Beneath the Underdog, in his essays, and finally in his talk here. The rush of words, the abrupt shifts in subject (sometimes in mood) testify to this. I usually understood what he was talking about and shared much of his taste and affection for the music and its creators. We also came to share jokes, drinks, and the latest political outrage.

Still, talking with Mingus? It was sometimes intimidating and, depending on his mood, now and again fraught with dense pauses and occasional disconnects. After a time I learned not to try and fill the dead air. And it was just a great privilege to hear him light up on a topic—as you will hear too.

Mingus, I came to think, felt forever on the outside of a world he repudiated yet was very much part of. Outrage and joy were commonplace emotions with Charles; they enabled him to carry on, or to beat the devil. For all the critical analysis that has been directed at him, maybe the most plausible thing I can say is that while he put up with deprivation and scorn as a black man, he was clearly very privileged as an artist. Mingus understood how degrading the business of performing jazz often was, but he had no doubts about how good he was and what he had accomplished. That perceptual discord often made him angry: “If you’re going to be a physician or a finished artist in anything, like a surgeon, then you got to be able to retrace your steps and do it anytime you want to go forward, be more advanced. And if I’m a surgeon, am I going to cut you open ‘by heart,’ just free-form it, you know?”

The avant-garde pretenders made him crazy because they posed as “ready-born doctors.” Their pretensions put the lie to everything Mingus had worked and studied to do in music. A further dilemma was that he, by most critical accounts, was labeled an avant-gardist. Another thing to make you crazy. The audiences and critics sometimes made him crazy.

Mingus had other demons that pursued him. More than most jazz musicians, he was always critical of his output, always trying to discover how to get away from jazz and create some kind of ideal, eclectic music that could truly represent and fulfill him. His paranoia was legendary; his imaginary ramblings and distortions, especially at this period in his life, tested both his friends’ and an outsider’s credulity. Except for drugs (which he never got into), his life, like Bird’s, was in some way a testing of every limit of excess. It was all part of a spiritual quest that he couldn’t really identify.

I don’t want to defend or excuse the outrageous and hurtful things he did—and there were plenty of those. Jazz people have sometimes gotten off the hook for behaviors that would put the rest of us in jail. Bud Powell’s beating at the hands of Philadelphia cops is certainly the other side of that coin. But Mingus—because he was verbal, very smart, and loved the limelight—never hesitated to put forward that duality of race and art, outrage and joy, that made him such a unique voice in jazz.

As composer and bandleader, Mingus seemed to have two models—Duke Ellington, of course, as many have noted and, to a lesser extent, Jelly Roll Morton. He had Morton’s swagger and some of Duke’s charm, though surely not his urbanity. His music was often Ellingtonian in concept, if not in execution, and like Morton, he found a way to bring what he called “spontaneous composition” to jazz. As a performer, Mingus brought supreme execution and brilliance to, of all things, the bass. No one in jazz has ever played that instrument with his musicality and skill.

Like many people who met and spent time with Charles, I was at first bowled over by his insights and humor, his knowledge of jazz, the jazz business and its people, and the quickness of his mind.

Never mind that I had trouble translating the staccato yet slurred speech that issued forth. It was like listening to the Source, the Buddha, the Wizard of Jazz. Eventually I found I could not only participate and engage with Charles but that we could converse. That has to be one of the great kicks of my life, and I must presume others who have had that experience would agree. Mingus wanted such exchanges, though he sometimes frustrated them by acting like a Toscanini.

Village Vanguard founder Max Gordon noted that there wasn’t a lot that was lovable about Mingus, but you could be his friend. In our talks, I sometimes got the sense that Mingus was performing, but it was the performance of a man who believed in everything he was saying—for the moment and maybe forever. Moody, he could clam up and offer the most laconic answers, or he could spout like a geyser, and you soaked it up and followed his rush of words to the end—or the next jump in subject. Yes, it was like his bass solos. And if you were lucky, you could say something that advanced the conversation.

I’m still not sure why I got on with him so well that he chose to reveal some very personal and painful hurts and feelings—not to mention his sometimes brilliant musico-socio-cultural aperçus. Part of our association, brief as it was, hinged on my attempt to be totally open with the guy. I was also willing to engage with him in writing a book, and that effort seemed to him a way to set the record straight, to talk about the realities of his life in music beyond the stylized attitudes and limits of Beneath the Underdog.

Mingus’s health—mental and physical—came up frequently in the course of my talks with him and with those whom I interviewed in the course of doing this book. He was terribly concerned about it and mystified by the symptoms he experienced. Who can say how far he saw into the depth of his situation? In 1974, five years before he died from ALS, his physical appearance was far different from what it had been two years before.

In our lengthy 1974 interview with Sue (see commentaries in chapters 6 and 12), he sat on the floor while she and I did most of the talking, contributing little but listening to everything. He looked tired but there were flashes of the old Mingus, with talk about cigars and food. His music was still good but of a different quality than the music of two years earlier. This was the period of Changes One and Changes Two, with George Adams, Don Pullen, Jack Walrath, et al.

It was a time when Mingus and Sue seemed to have reached an equilibrium in their relationship, and perhaps he had resolved some of the tumultuous feelings of the past two years. But at best, it was Mingus in coasting mode. The second Friends concert on January 19, 1974, featured an exceptional reunion with Rahsaan Roland Kirk, and in May we had a book proposal in to Doubleday, the one already mentioned that ultimately fizzled. In July he undertook a long, too-strenuous tour to South America, Europe, and Japan.

I saw Mingus one more time performing at a club in New York in 1977, and it was not a good evening. For someone who was more alive than anyone I’ve ever known, he looked drawn, the music was dispiriting and our reunion perfunctory.

But the reality of Mingus playing, talking, bitching, and dissecting the world around him remains totally unforgettable to me. When the man was energized and the creative force was flowing, when the words rushed out and his thoughts tumbled over one another, it was indeed a window opening on the process that made such extraordinary music.

After so many years, I continue to miss him.

After the first Mingus and Friends concert in February 1972, I came back to New York in May for my first real exposure to the man. He was scheduled to appear with the band on Julius Lester’s Free Time PBS-TV show. I drove in from Pennsylvania (where I then lived) to attend, wondering how Mingus would get on with the show’s host, Julius Lester—musician, writer, outspoken civil rights iconoclast.

Lester had been tied in with SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), had gone to Cuba with Stokely Carmichael, and had written a book that some of us read for its great title, Look Out Whitey! Black Power’s Gon’ Get Your Mama! But word had it that he was changing his tune. At that point, I didn’t know what Mingus’s tune would be on such subjects.

Finally off the plane from Boston, Charles walked into the WNET studio in a long leather coat, carrying an enormous shopping bag of bagels, salmon, pickles, peppers, and cream cheese. Sue and I and the band were already there and, before anything else happened, the bag was opened and the contents set out for all to share. The rehearsal went well, as Mingus felt calm and in charge. He and Lester got on famously, and the show was mostly music (as I recall it) with a minimum of talk.

The band was his regular group at the time (May–June 1972): Charles McPherson, alto; Bobby Jones, tenor; Lonnie Hillyer, trumpet; John Foster, piano; Roy Brooks, drums; and the leader was starting to play like the Mingus of old. Joe Gardner might have substituted for Hillyer in the group playing on the recording I made in Philadelphia in June. I can’t be sure.

The first extended interview we did was over a kitchen table (Mingus was never far from food) at Sue’s place on East Tenth Street—as it happened, about a block from where I used to live (from 1965 to 1971), and it felt good to be back on that familiar turf.

A young man from some Italian publication had come to interview Mingus too, so he went first and I was happy to sit in and tape the proceedings, after which Charles and I would talk alone. Sue was also present and made an occasional comment.

What followed was about an hour of vintage Mingus, an interview which opened up many of the themes he and I would subsequently pursue over the next three years. It was also remarkable in showing the mixture of deference and disdain that Mingus could muster in the face of some remarkably stupid questions—even allowing for the language problem.

The interview covered many of the topics we would discuss later on:

Watts, race, and politics;

ethnic music for the people;

phony African music, black intellectuals;

Mingus music, as it comprehends all music;

electronics in music;

tradition and study;

jazz audiences.

The session was typical of the way Mingus intertwined his thinking on race, politics, economics, and music and thus can set the scene for what follows in this book. I’ll interrupt occasionally to add a gloss or two.

• • •

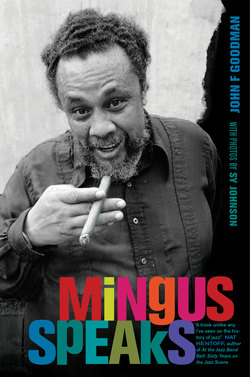

FIGURE 1. Mingus with cigar, on his rooftop, 1974. Photo by Sy Johnson.

INTERVIEWER: And how do you sympathize with the view that music, and most of all, jazz, reflects a state of mind or a human condition?

MINGUS: Man, will you rewind that statement again—rerun that?

INTERVIEWER: Yes. Jazz is a very old form of music that started a long time ago. I don’t know exactly when it came to life, but anyhow, we are now in 1972, and many things have happened. Does 1972 jazz reflect what has happened during this last part of, uh . . .

MINGUS: No, of course not, ’cause nobody knows what happened. How’s the music’s gonna say what happened, when nobody knows what’s happened [anywhere] in the last seven years?2 There’s been a camouflage by the government to make it look like there was some black race riots when there wasn’t any at all. They probably hired people to do it; I can’t figure it out for sure—I’m trying to look at it from the people I knew on the inside who were involved, who lived in Watts. It could be the Communist government or the Nazis or even the American government, or it could be the Southerners. I don’t know who, but somebody set it up. The police department, maybe, I’m not sure.3

Do you know what I’m sayin’? I want to be sure you understand what I’m sayin’. I think they hired a few people . . . that camouflaged a revolution, the black revolution. But the real one is about to begin, ha ha.

INTERVIEWER: You see, our audience knows you very well. However, I wish you could give, you know, for our audience, a sort of little rundown on how you started, from the very beginning. It has to be brief, you know, but I really would like to start there.

MINGUS: I’ll do that for you, only be sure I answer the question, the first question. You said, you know, does the music reflect what is happening or what did happen. And I say again, it can’t because no one, no black man, knows what happened yet. Maybe me, maybe a couple of others, I’m talkin’ about musicians that know. I’m not too sure of that—McPherson [Mingus’s alto player] said he thought the riot was a fake, looked fake to him.

• • •

In typical Mingus fashion, he leads off by throwing a bomb at the interviewer. His point of view about such things was generally to take the inside track from his own experience, whether the subject was politics, music, or social concerns. It’s no wonder that he and the poor Italian guy were often at cross purposes. This happened frequently in his other interviews too, and sometimes Mingus would deliberately exploit the disconnect. Later, Bobby Jones would tell me that this was a trick to throw the interviewer off the track.

Watts and race (theme 1) would reappear shortly. Now he was getting into music as food for the spirit (theme 2), a favorite topic.

• • •

INTERVIEWER: Well, as a matter of fact, you know, I heard an awful lot of black Americans speaking in terms of, we are acquiring a new sense of awareness, or something. Do you feel that music, and in particular, jazz, can help, you know, these people to better understand themselves?

MINGUS: Well, if good music could get to the minds or the subconscious of people, it could help everybody, not just racists. Music has been used as therapy, you know, in mental wards. I was told about a program on NBC television about using poetry with schizophrenics. When I was a child, in 1942, they were using music as a shock treatment to patients. For example, I think music was used to uplift people in the first Russian revolution. So you don’t even need me to answer that question.

If the people are separated from their music, they die. If the black people have a music, if jazz was their music—umm, although the masses of black people never went for jazz; they were segregated from it; they went for rhythm and blues. Not rock blues, rhythm and blues. That’s probably why they’re so confused and so separated, because they don’t have a religious music like the Jews, who never changed their music; the Greeks, who never changed their music; the Armenians; the Italians never changed their music. But the black people don’t have a music, actually, unless that is gonna be jazz. But I would say jazz is for a progressive black man; it’s not for the masses.

I still think that the black people like the blues—the original blues, the T-Bone Walker blues. I don’t think they’re growing out of that or ever should grow out of it, until the blues is killed, you know, until the reason for the blues has died away. It shouldn’t be a sudden change, it should be a gradual progress of society to rid itself of the things that causes the blues.

INTERVIEWER: You see, you as one of the most outstanding representatives of the jazz world, how do you view, how do you visualize, this new revamping of gospels and spirituals here in the States?

MINGUS: Revamping? It’s Madison Avenue doing that. Gospel went away in a sense, but it never went away for the people who liked it. They still bought the records and listened to Mahalia Jackson, things like that. And we haven’t lost any jazz fans, it just seemed that way [because jazz] wasn’t publicized. The concert I just gave at Philharmonic Hall proved we never lost anybody. We had three thousand people. (I give Bill Cosby five hundred because he wasn’t actually performing) and most people just came to hear the music. I’m saying that, uhh, I never lost any fans. I stopped recording, but the people never forgot, the ones who originally heard the music.

I’m not sure I could put it on a competitive basis because I don’t know if an artistic music is supposed to appeal to masses of people. The black masses didn’t go for our song; America went for it, but those were mainly white people. The black people still was for gospel music, and, uhh, blues, not rock. They used to call it race music, way back in the ’30s and ’40s. Then they called it rhythm and blues. And later, country and folk which was for the white people. [To me:] Do you remember those days—were you around then?—country folk music?

And then one day they kind of amalgamated all of it—Madison Avenue did—because the thing was to sell to both black and white, and jazz would not have sold if they had kept on pressing rhythm and blues records. But you can’t beat the system. Right now if one company had enough guts to stay with the rhythm and blues and with the country and western—you got a lot of cowboys who still want country and western only. My mother used to listen to cowboy music, what they call country and western, and she wasn’t white.

INTERVIEWER: What part of the country was that?

MINGUS: I was born in Arizona and lived in Watts. And that’s why I know the Watts riot was a fake. Many of my friends were out there, and Peter Thompson and Dr. Ferguson—they don’t even mind their names being called—when they saw the riot happening, one of these guys was a doctor and he went to his roof to get his gun to protect himself from the people who were starting to riot.

It was strangers, black people breaking down doors of groceries and stores, and they disappeared immediately on a truck. It was very organized, like a strategic plan. And as soon as they got on the truck, three, four, five minutes later, in come the police shooting at everybody that was black. So, as I was gonna say, it was a Madison Avenue race riot in Watts. A few people would say Newark [1967] was the same way. . . .

INTERVIEWER: An awful lot of black intellectuals say [musicians should] bring the African tunes, you know, from Africa. For example, I’m speaking in terms of a musician like Quincy Jones, like Ornette Coleman—they have gone to Africa and then they wrote some music stating their inspiration had been African, like Mataculari or something, it’s the name of one of the latest LPs [Gula Matari] by Quincy Jones. How credible is that supposed to be for you?

MINGUS: [Calmly, not provocatively] I don’t know what they’re talking about, but I’ve been exposed to African music for about forty years. I’m trying to think—l know they’ve got music of the Bushmen on records, but I was never there. But I found that they’re making a lot of these records right here in Harlem.

INTERVIEWER: Excuse me, where did you go to?

MINGUS: This was in California.

INTERVIEWER: No, no, I mean for the Bushmen music?

MINGUS: This was, I’m trying to think where it was, South Africa, Bushland. A friend of mine in Mill Valley named Farwell Taylor always used to play African music for many years.4 He had this huge drum that he used to sit on. It was kind of like a drum in the shape of a tree, and you blow into it. I used to know the names of the tribes of music, but it’s been so many years ago, I’ve forgotten.

INTERVIEWER: Bushmen Negroes in Jamaica, and in Surinam—

MINGUS: It’s nice that these guys are discovering the music, when it’s been there all the time. Hollywood has used it, you know, and Phil Moore did the score for a movie, The Road to Zanzibar.5 You can look it up in [Joseph] Schillinger and find most of the theories of African music.6 You can’t really learn how they send messages, and all that, from the music, but you can get the nucleus. There’s nothing new, there’s always been African music.

INTERVIEWER: Probably it is new for us, because we are not used to it. Now, how about going back to my second question that I proposed to you before. We would like to have a little bit of rundown on your past life.

MINGUS: Well, I don’t see why I gotta do that, cause you can get a book and read that. My whole life is in it.

INTERVIEWER: But if you say that to my audience, my audience may even believe that I’m shitting around, whereas if you do say that, and they hear that, from your very voice, then they probably, you know, really . . . would lend their attention.

MINGUS: Well, take an average record[’s liner notes]: they tell you some history of a guy, when he’s born, April 22, 1922, Nogales, Arizona . . .

INTERVIEWER: No, I don’t want you to give me this kind of news. l would like, artistically speaking, you know—say, if you have changed from one style to the other style and how are you—

MINGUS: I don’t change styles. I’ve always been a musician, whatever kind you want to call it. I studied music in school, and I always did things to get a job—if I could get a job playing any kind of music, I would do that, you know, but I had one music in mind, as a goal, and there’s only one music. And that’s all music, you know. It may encompass a lot of other musics, but in the meantime I’m working in jazz, and I play in that medium. But my goal is much higher than that. Not that I think black music or African music or any kind of music is inferior—it’s just one kind of music, you know. I can’t say to myself there’s just one kind of music ’cause I like all kinds of music, if it’s good. I like all kinds of music, particularly folk musics from different tribes of people.

• • •

I think Mingus looked at all music as basically deriving from folk music, and he certainly heard the folk forms in concert music, particularly in Bartók and Stravinsky. Disguising them, “revamping” them, putting them in stylistic boxes for sale, was a way to dilute, if not kill, the folk spirit.

The black blues for him was a way to reunite black people musically and spiritually. Avant-garde free jazz was simply an arcane way to deny the spirit because you could play it without being a musician (theme 3). You had to study and know the blues-in-jazz tradition to be any kind of serious jazz musician and play for the people.

This idea came up frequently in the course of our later talks.

• • •

MINGUS: As I’m sayin’, the black people of America don’t have a folk music, unless it be church, which is pretty corny, or the blues. Joe Turner is closer to it and T-Bone Walker’s closer to it than some of the people they have today [that] they call blues singers. But the spirit of Billie Holiday, she has the blues spirit; so did, uhh, who else? Sorry, she’s the only one I know that’s got a jazz, a pure blues spirit, which is religiously involved without the Christian tones. [Pause.]

I don’t know how to say it, man—[whatever] music the black people would adopt would have to give them a chance to hear all kinds of music and then find what they like. I find certain types of black people like, still dig, Charlie Parker. They took that as an awakening to them. There’s a certain type or class of person who still digs Bird. They’ll always dig Bird, or an extension of Bird. They like Charlie McPherson and the way he plays ’cause it reminds them of Charlie Parker.

Bird’s music is a very hip thing, but, uhh, I find there’s something lacking in it for me. It’s not enough. There’s not enough complex harmony, theoretically, for me. I enjoy more complex harmonies, or no harmonies. I don’t particularly like chord changes all the time. I like many melodies at once, created without a chord in mind, that may form a harmonic chord, you know? I can tell, usually, if it comes from one man’s mind, or if it’s mechanically done, or if he heard all these melodies at once. I feel that if a man writes four melodies at once, he’s got to play them at once, and he hears them at once. If he expects people to listen to those four melodies at once—or five, like a Bach fugue—then he must conceive these all at once. Not mechanically put them together because he has a theory that says it will work.

I’ve been working—rather than doing written compositions—to do spontaneous compositions where I’ll do some string quartets, some of ’em by meditating and playing, some composing from the piano. “Adagio ma non troppo” from my latest album on Columbia, well, that was a spontaneous composition. It had about two or three melodies going at once. It’s not that complex, it’s a lot of feeling and emotion, but it’s not meant to be intellectual, or anything like that. I don’t know any intellectual niggers—what’s an intellectual black? Is it that intellectual blacks are going back for African music?

INTERVIEWER: Yes, as a matter of fact, you know, an awful lot of them do. I’m not speaking only in terms of musicians, but even of playwrights, writers, artists, visual artists, or performing artists. There is a tendency now, you know, which strangely relates well to the first Harlem Renaissance, that politically was probably reflected by Julius Garvey and Booker T. Washington, this kind of back-to-Africa movement.

MINGUS: You mean Marcus Garvey?

INTERVIEWER: Marcus Garvey, that’s right. So I was wondering whether you too were on to this, cognizant of that.

MINGUS: See, I don’t know how to deal in terms, like you say, this guy’s avant-garde, or this guy’s intellectual. I don’t know how to be any of those things. I’m just me, man. I don’t see how you could possibly be in these 140 years a black intellectual. A black intellectual means you should be able to cope with Einstein, a guy goin’ to the moon, plus cope and communicate with the guys in the Bowery. That’s what a black intellectual means to me. But he don’t exist—[someone who will] go down where the bums hang out—and so anybody who’s been sittin’ in front of a television set claiming to be a black intellectual to me is a phony. I haven’t met one yet, ’cause he doesn’t know the people.

I been tryin’ to get to be—I didn’t force myself, but by being kicked out of my position, my financial position and everything else, for the last six years—I got to become a bum, and live with people who were poor. And [to] even like them more than people who were successful, and not want to move away from them, because they were more for real than the rich people I’ve been around before, or the half-assed rich black people, you know, the ones who are satisfied with selling their own people out for a few more write-ups and a few more dollars.

[Pause.] What else?

• • •

End of solo. One of the reasons you have to love Mingus is for his capacity to demolish such concepts as “black intellectuals.”

• • •

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, well, what else now? I just would like to go back to your music, you know, if you don’t mind. You mentioned your latest record on Columbia—are you now working on a new album?

MINGUS: Well, it probably will be an album because George Wein’s people always record at Newport [in New York], and some way I’ll have a big band there, and a couple of weeks before that I’m going to be at a theater. If everybody comes from Italy, tell them to come to the Mercer Arts Theater.7 I’ll be working the band out there, plus I’ll have a string quartet, not the usual—I’ll have two cellos, a viola, and violin. And I’m going to write some music for that. It’ll be at the foot of the program; we’ll do Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, too.

• • •

Enter new theme (4): electronics in music.

• • •

MINGUS: I think it’s time that good musicians get rid of electric instruments, because a good musician can’t play an electric instrument; it plays you. For instance, if you want to bend a note, you’ve got to push a button to bend it. You can’t control the dynamics. You play soft-loud with the bow on a violin, but it all comes out the same volume on the electric machine. You’ve got to have another hand to turn it down soft and low. So it’s not meant for real music, it’s meant for someone who is not sincere about playing how he feels.

INTERVIEWER: You may probably clarify for me one idea I’ve been acquiring by being here, by interviewing other people. Is it really true that jazz is getting a little, uhh, shall I say, is getting into rock and rock is getting into jazz?

MINGUS: I don’t know what musicians you’re talking about—not me. All I know is if you guys are going for electric instruments, I’ve heard nothing better than a Steinway yet, all over the world. I’ve heard nothing better than a violin. Electric music is electric music. If a guy uses this music, then he’s not a serious musician. I mean, they’re not gonna make a better piano, man.

INTERVIEWER: Then wouldn’t you agree with me that electric music today is probably 1972 stuff. I mean the equipment is sophisticated, the gadgets are kind of hard to grasp, you know, wow.

MINGUS: Well, I’m tryin’ to say something! If you want, if a man was free enough, he could take an ordinary symphony with ordinary instruments and be more atonal and farther out or weird or avant-garde with everyday instruments, because of one thing—you can control the dynamics. There’s nothing you can’t write for a full orchestra that electronics are doing [any better].

Electronics are doing the same thing in music as elsewhere: they’re replacing people. Push a button, it sounds like an oboe, but not a good oboe player; another button, sounds like a French horn. The guy who plays this stuff is a nigger because he can’t afford to get a violin player or a French horn or oboe player. He might like to have the oboe—I would—but [he] will go to the commercial extreme because it’s popular to use electric instruments.

And the great men like Charlie Parker and men who played legitimate instruments would laugh at these guys because they’re not in it for the love of music but because they think they’re going to make a lot of money—like Miles Davis did. Miles didn’t even need to make any money; he was already rich, or his daddy was rich, so I’m not even sure if Miles made that much money, I just assume he did in music. But I know he’s an electronic man, and eventually somebody like me is going to make him come back and start playing again, put that bullshit down and play his horn. He’s gonna have to because [otherwise] he’ll be laughed out. Because you can get a little kid to push a button, and with these machines they got now, it’ll sound like they’re right.

Look what happened for seven years in this country. Most of these kids couldn’t read a note or sing in tune. But electronics can make ’em sound OK: they hit a wrong note and you push a button and it’s in a vibrating machine plus an echo chamber, and it’s [sings] wooo-wooo-wooo-wooo, so you don’t know what note he’s singing. But I want to hear a singer, man, I don’t want to hear nobody bullshitting.

I want to be able to go to a hall with no mikes and hear the guy play his cello like János Starker. If he can’t play it, send him home. Give him a rock-and-roll instrument and let him play. But don’t tell me he’s no musician, don’t put a musician label on him. Say he’s an electric player, find something else to call him.

The guitar players, they have a little bar on the neck of the guitar, so if you want the key of B-flat, they move it to B-flat position; for the key of A, they move it down to A. That way, they only have to learn one key, they can play in the key of C all the time. I was on a TV show with a guy like this and I say, “Do you move the bar on your guitar?”

He says, “Yes,” and I say, “Why do you do it?”

He says, “It makes it easier.”

I say, “Well, why doesn’t Jascha Heifetz do it? Why shouldn’t he play everything in the key of C?”

I mean, are you goin’ to kill the fact that people can play in B-natural and A-natural? That’s what Madison Avenue is trying to do, man. [Pause]

I don’t believe in everything about classical music. I don’t believe in stiff classical singers. I think there should be more folk voices in it. A lot of things could be changed, improved on, and people are doing that, like Henry Brant.8 He did an opera, with classical singers, but he also had a hot-dog man—and other people who would just be singing what they felt, really. [Sings:] “Hot dogs!” you know? “Peanuts!” you know? [Laughs.] That’s the way the old Italian operas were, and weren’t they kind of for real? [Imitates basso voice singing:] “Would you buy my popcorn?”

• • •

They took a break after some talk about Northern Italians, blond Italians, Sicilians, and pizza men. But Mingus wanted to get to one of his favorite points, about jazz tradition, styles, and “progress.” He understood that art moves by fits and starts, that there is rarely a straight line of influence or stylistic development. At the same time, if an artist couldn’t understand and incorporate tradition, he’d never be a creator. And if he couldn’t master the fundamentals of music, he’d end up being a fraud.

All the previous themes were coming to a recapitulation.

• • •

MINGUS: See, this thing you call jazz: if Lloyd Reese, Eric Dolphy’s teacher, my teacher, had become famous, Dizzy Gillespie would have never made it—because Lloyd played like Dizzy back in 1928. So I’m trying to say that even though Louis Armstrong and King Oliver and those guys came along, here was another guy who knew a little more, had a different kind of education in music where he could have been playing atonal then: Lloyd knew Schoenberg, Beethoven, Bach, he’d studied that. He’d be playing those kinds of solos, and guys would say, “He’s out of tune.” Therefore people have to come in line, follow the next guy, step by step, “OK, that’s progress.”

Charlie Parker was the most modern thing, but actually I should have come before him because I had a whole new thing that had the weight and had to do with waltzes and religious music—a period of my music was like that. Then Bird should have come in, but instead they completely ignored me and I had to go play Bird’s music. Which I’m glad I did—I learned a lot from that—but it’s not honest because it makes kids come up and think [jazz has] gotta fit to this form right here.

Now it’s gone to the other extreme: each guy’s gotta be different, and now this is where they all full of shit. If you’re a musician today, man, you shouldn’t be playing like Louis Armstrong. If you’re a trumpet player, you should be playing like Dizzy, Roy, Cat Anderson, Maynard Ferguson, all them guys or you ain’t no trumpet player. If you play bass, you play like Mingus, Oscar Pettiford, Ray Brown, all them bass players or you ain’t no bass player. You should be able to play like Art Tatum first or quit. I was a piano player and I quit cause I couldn’t do Art Tatum. I knew I couldn’t make it.

It’s like when you go to Juilliard, they give you all the things composers have done, and they say “study it.” After four-five years of you studying, one day they say, “Now, let me see you write something that’s good.” And you’re going to think, because you know damn well that teacher knows when you’re lying and stealing from over here or over there. You’ve got to throw all that out of your mind and compose something. And only the person himself knows, and most of the other guys quit if they know they can’t cut the guys in the past.

But America gave us a new thing, it’s called avant-garde, which nobody has ever explained, for Negroes. Some of these guys, you know [does flutter-tongue trill and a squook-squawk] as long as it sounds undescribable [they think it’s music]. It’s not music, because in the olden days a guy had to play his solo back. I met one of these guys and said, “Can you play this off the record?”

“Of course not, man, I don’t want to.”

I said, “What if I wrote it down, could you play it?”

He said, “You couldn’t write it.” That’s bullshit. I can write it but he can’t play it ’cause he doesn’t know what he played.

And I’m tired of these people fooling our people. Because if you’re going to be a physician or a finished artist in anything, like a surgeon, then you got to be able to retrace your steps and do it anytime you want to go forward, be more advanced. And if I’m a surgeon, am I going to cut you open “by heart,” just free-form it, you know?

We’re on an island and you say, “Look, man, use a book.”

“No, I don’t need no book, I’ll just ad lib it.”

“Well, look, Mingus, we’re out here by ourselves, it’s dangerous, and I don’t want you to make no mistakes, so just look in the book.”

“I can’t read, man, I don’t read no music, but I’m going to cut you open and take out your appendix ’cause it’s bursting.”

Well, you’re gonna hope that, since I’m the only guy there, I will look in the book. Don’t take me for no avant-garde, ready-born doctor. Don’t let nobody fool me and tell me that they’re avant-garde, don’t need to study—and make the black kids think they don’t need to learn how to read to play flute, oboe, French horn, and all the instruments.

Let these people know that there gonna be openings in all symphonies everywhere in the world for them and that jazz is just one little stupid language hanging out there as a sign of unfair employment. Jazz means “nigger”: if you can’t get a job in a symphony you can get a little job over here where you get a lot of write-ups and no money. But you’ll never get in the symphony. Maybe in all America we’ll hire one of you guys for the Philharmonic, one for the Jersey Symphony. We’ll let these two be a sign that we found two good ones.

Now we know goddamn well that we got a cello player better than any you all got—what’s his name? Kermit Moore—he’s better than János Starker, man, warmer, plays more in tune, I couldn’t believe him. You’ll hear him in my string quartet.

Yet the white man can go on forever saying, “Well, we’ve got Jascha Heifetz . . .” Sure, but we may get one of them if you free the kids, I mean little babies, let them come up and think there’s a place for them. Wouldn’t you feel good to think that someday we’d have another Jascha Heifetz, regardless of what color he was? It don’t have to be Isaac Stern or Yehudi Menhuin. They don’t always have to be Jews, right? It’s kind of weird they all Jews [laughs].

I’m trying to say let’s find out what jazz is. Jazz is, or was, a very powerful force before seven years ago to a certain group of white people. They hid the sales of the records, they didn’t let you know how many they were selling, they gave the guys a lot of write-ups, very little money. First place, second place in the polls—when you took third place, you didn’t work no more. White or black, Red Norvo, all the guys, once you’re voted out of first place, you’re in trouble, from Lionel Hampton to all the rest of them.

SUE: He just sent all his medals back [from the polls he had won].

MINGUS: I don’t want none of them damn polls. I know what kind of bass player I am. I auditioned with the San Francisco Philharmonic in 1939 and I was the best one except for one guy, his name was Phil Karp and he got the job. But they hired three bass players and I was better than the other two, and the conductor told me they just couldn’t do it. So I know where I’m at.

And I’ve been waiting till the day when I get a chance to write classical, pure, serious music that came out of all the musics. For a guy to go study Africa—fuck Africa, man. Now here’s the guy I’ll study with: I want to know how those guys do this [beats a complex rhythm] and send a message in Haiti. You go to Western Union and you live in the mountains like Katherine Dunham, when you get a wire it don’t come on no piece of paper. In the mountains it comes to you on the drums. And they bring it to you by mouth. Now, those guys, when you get to that, I’d like to study that. ’Cause some guys in America think they can do that—one is dead, Eric Dolphy.

• • •

Now the coda. After an hour of turning the interviewer’s mostly general questions inside out, Mingus changed key again and offered up an analysis of the jazz audience, bending the question to his own purposes.

• • •

INTERVIEWER: One last question, what is the American audience like towards jazz . . . nowadays?

MINGUS: Well, each town is different. Let’s put it like this: I’ll try to tell you the best towns in America. For Charlie Parker’s music, the bebop period, when we went to Philadelphia, I couldn’t believe how people loved Bird. And they listened like you could hear a pin drop. Bird played there ten to twenty times a year when he was popular. I’ve always had the same following and I recognize the same faces in New York. At the Half Note Club, the Five Spot, and the Vanguard for the last thirty years, I recognize the faces, can call a lot of the names. Some get married, bring new husbands, new wives, but they still come back.

Now what are they like? My audience is very, very hip, and some of the young hippies are starting to dig me, I don’t know why. Maybe because some singer called my name on a record—do you know that guy, Sue? Right, Donovan. I think it did me a lot of good. I was in San Francisco when it first came out and I used to walk by this college, and kids would say, “There goes Mingus,” you know, and before the [Donovan] record came out nobody’d say anything.

American audiences are not like Europe. But I tell you what is better than Europe is Georgia, Tennessee, the South—they are just now waking up to jazz. They got jazz in by television. And the places where Martin Luther King picketed, they’ve changed, the integration is there. It’s not overdone, the people sound like me, they’re for real, they try to be serious about it, listen like it was classical music, same way I listened when I first went to Europe. It was a hell of a feeling to go to the South and have that happen, man. ‘Cause when I went to the South [in the late 1940s] with Lionel Hampton, man, there was just noise, dancin’, jumpin’ around, and drunkards. I couldn’t believe [the change], man.

So I haven’t been to Europe in quite a little while, but the audiences there have always been the same as—what’s the closest thing to classical? Sarah Vaughan when she was first making it? They used to give her a lot of respect, just like a classical singer. They’d treat her just like Marian Anderson or Duke Ellington in the ’40s and ’50s. When you went to his concerts some people wore tuxedos. They knew it was a pure music.

Bird never got that. Bird always got the balling crowd, people high on something, very hip, swinging, hustlers and pimps. Which is nothing wrong, just saying what he had. And from all races. In Philadelphia he mainly had the black hustlers and pimps. As far as people accepting—the last crowd I had in Philly was a pretty good crowd, pretty good audience, because I recently had a concert there with the big band. I guess there were some of Charlie Parker’s people there too, because I’ve been there with him so much. I guess they remembered him and especially because I recorded with him too, ’cause there’s a mixture of audience there, plus the hippies are starting to show too. The clean little kids with the Levis. I can tell you how they look, but how they feel—they don’t feel together yet. I feel this is an assorted crowd, they’re searching for something. It’s not like it used to be.

Like when you went to see Count Basie you saw a Count Basie crowd. You go to see Duke, you saw a Duke crowd. The two didn’t meet, man. The people who dug Basie did not dig Duke. If you had put jazz together like George Wein does now, you wouldn’t have made it. You would have had one section booing the other. I can’t prove this, but I’m pretty perceptive about feeling out audiences and things.

For instance, I’ve always had the knowledge about how to please an audience, which I don’t do. Anytime I’m uptight, I got a thing I do with an audience which I guarantee will get applause for one of the guys in the band. Not what I do physically but do musically. But I don’t like to do it. I call a solo and stop everything behind the soloist, leave him play by himself, and then when the rhythm section does come back in, the people always go crazy. What are the reasons, I don’t know, but that’s the way you do it.

To answer your question better, I’m glad there is a European audience. I’m trying to think where the best in Europe was for me—France, and Italy, and Germany—all very close. In Italy we were near Rome. Do you think in Europe it’s always the same audience that goes to hear [someone]?

INTERVIEWER: No, I wouldn’t say so. They actually are not so prone, like here, to be a one-man audience. Maybe probably a two- or three-man audience.

MINGUS: I haven’t checked this, but there’s a club in Boston, and after I closed there, I went back and didn’t see anyone I saw when I was there earlier. It was a whole different kind of people that came to see that next group. Plus, that was a good sign because they were known there, and it was packed. So whatever you call jazz is coming back, evidently, in this country.

• • •

If you read the interviews and books in which jazz players talk candidly—like Arthur Taylor’s great compendium Notes and Tones (Da Capo, 1993)—many if not most support views like Mingus’s, in particular about the necessity of education and training in jazz. Other musicians have been willing to broach the phoniness of the New Thing, the false call of Africa, the need for black people and their culture to reunite. But few have come down as emphatically as Mingus did about these things. You know, there’s a strong “don’t criticize your brother” injunction among jazz people.

Despite that last remark about the club in Boston, I think he saw traditional jazz culture (and the audience) disappearing and wanted to save it.

NOTES

1. The first comment is from Ross Bennett, writing the Disk of the Day feature on the Mojo magazine website, at www.mojo4music.com/blog/2009/03/charles_mingus.html; the second, from “mikedurstewitz” in response to “Charles Mingus: The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady: Track A, Solo Dancer,” YouTube video, 6:39, posted by “bassigia,” Nov. 9, 2009, www.youtube.com/watch?v=17KTUqLyNcU. Other comments there are informative as well.

2. This is the first of several mentions of “seven years” or “six years” as the dark period in Mingus’s life. This term seems to signify, variously: a period of social turmoil, a bleak time of withdrawal for him personally, a time of musical decay and decline for jazz—perhaps all lumped together, as in some gloomy and sustained minor ninth chord. For this period, see Brian Priestly, Mingus: A Critical Biography (New York: Da Capo, 1982), 159–71. As to causes, Priestly mentions: the impact of Eric Dolphy’s death (June 1965), the growing displacement of jazz by the pop musical-industrial complex, the noisy rise of the jazz “avant-garde,” the diminishing size of the Mingus bands, a reduced number of club and concert dates, and, finally, the public eviction from his loft and school in late 1966.

3. The Watts riot occurred in the summer of 1965 and shocked the country. A Washington Post piece thirty years later, nominally about Waco and the Oklahoma City bombing, may help explain Mingus’s paranoid reaction. In it, author Virginia Postrel notes that those who burned Watts were never caught or tried. She affirms that “black inner-city communities are rife with conspiracy theories, with paranoia, some of it spread by talk radio: AIDS is a plot by white people in the government to wipe out blacks. So is crack. A few years ago it was widely repeated that an upstart soft drink made black men infertile.” Because inner city blacks believe the government’s message that “officially sanctioned violence is okay,” their paranoia continues, Postrel says. Virginia Postrel, “Reawakening to Waco: Does the Federal Government Understand the Message It’s Sending?” Washington Post, April 30, 1995.

4. Farwell Taylor was a painter and lifelong friend of Mingus, who introduced him to the culture and thought of India. Among other sources, see Todd S. Jenkins, I Know What I Know: The Music of Charles Mingus (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2006), 7.

5. Phil Moore, was a pianist, arranger, band leader and accomplished studio musician prominent in the 1940s. See “Phil Moore,” Space Age Pop Music, www.spaceagepop.com/moore.htm; and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phil_Moore_(jazz_musician).

6. Composer and music theorist Joseph Schillinger influenced many in the 1930s, including George Gershwin and Benny Goodman. See Daniel Leo Simpson, “My Introduction to the ‘Schillinger System,’ ” Joseph Schillinger: The Schillinger System of Musical Composition (blog), Dec. 16, 2008, http://josephschillinger.wordpress.com/; and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Schillinger. Mingus mentions in chapter 5 that his second wife Celia studied Schillinger.

7. Once labeled “the downtown Lincoln Center,” the Mercer Arts Center was an ambitious venture created by some off-Broadway heavy-hitters to provide venues for the performing arts. Management had booked Mingus and his Vanguard big band (see chapter 7) for a couple of weeks in July, and at the time of this interview he was excited and had begun rehearsing the band. Unfortunately, a neighboring hundred-year-old hotel collapsed on August 9, 1973, and caused the Mercer to close. See Emory Lewis, “Hotel’s Fall Was Also a Cultural Disaster,” The Sunday Record, August 19, 1973.

8. Iconoclast and experimental composer Henry Brant died in 2008 at age ninety-four. He promoted acoustic spatial music which combined different styles—classical, Indian, Javanese, jazz, burlesque, and others—with the special placement of instruments of his own invention. See David A. Jaffe, “Henry Brant’s Home Page,” www.jaffe.com/brant.html; “Henry Brant, 94; Daring, Prize-Winning Composer,” Washington Post, April 29, 2008, www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/04/29/AR2008042902918_2.html.