Читать книгу Mingus Speaks - John Goodman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

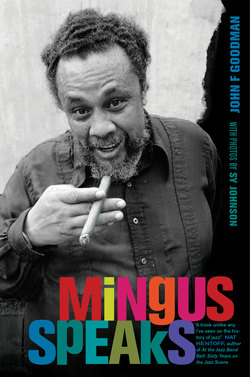

This is not just another book on Mingus. This is the man speaking in his own voice. From the outset I did not want to write another critical study or an analysis of the music. It had to be basically a book of interviews, letting the man speak in his own headlong delivery, constructing his own verbal solos, punctuating with blasts fired off at musicians and critics who didn’t measure up, with ramblings into paranoia and real pain. But I wasn’t sure how to give it a form so that his voice would be heard—and heard accurately.

With all the stuff that’s been written about him, there is very little in the way of extended interviews—and somehow he and I connected to make these happen.

Let me first give you some sense of who I am and where I came from—the bona fides in other words. I grew up in Chicago and its suburbs, fortunate to have parents who passed on to me their great love of music. As a toddler, I could identify the music in my father’s big collection of 78-rpm records by the color and design of their labels: the Vocalions, Victors, and Columbias, the music of Duke and Lunceford, Paul Whiteman, Chick Webb and Ella (on blue-and-gold Decca), most of the major big bands, Glenn Miller, the Dorseys, a few small-group things, some show music, André Kostelanetz (yes), concert and symphonic music.

In high school, a group of us devoted ourselves to listening to and playing jazz, starting with Dixieland and small-group swing. We were early-’50s examples of what Norman Mailer later called white Negroes: we read Mezz Mezzrow (a Chicago guy);1 aspired to be hip and cool; and made frequent weekend trips to the city to get drunk and hear some of the great old-timers—Baby Dodds, Henry “Red” Allen, Chicago veterans like George Brunis and Art Hodes, and of course the Ellington and Basie bands when they played the Blue Note. In 1954, a friend got us into the recording session for Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy. We sang background on a tune or two.

My parents and another couple had given a celebrated party in 1950 featuring Armstrong’s then-all-star group (with Jack Teagarden, Barney Bigard, Earl Hines, Arvell Shaw, Cozy Cole, and Velma Middleton). That event was talked about for years and still provokes pungent, sharp memories: Louis and Hines noodling at the piano; Jack T’s famous trombone case with space for a clean shirt and a bottle of gin; my high-school friends sneaking by the cops and sitting on the lawn. There followed other musical functions—Oscar Peterson’s trio at the Ambassador Hotel in Chicago, pianist Barbara Carroll in our living room, and a few more.

My father, who should have been a George Wein, promoted a series of country-club dance parties which featured the great bands of Duke Ellington, Les Brown, and Count Basie—dancing on the terrace, the saxes right in your face, loud and swinging. My mother had regular season tickets to the Chicago Symphony throughout the Fritz Reiner era and earlier, when the orchestra was finally achieving greatness. I had heard and studied the “standard repertoire,” this orchestra’s meat, but attending live performances in the acoustics of Orchestra Hall was to hear soloists like Rubenstein, Heifetz, and Dame Myra Hess in unforgettable explorations.

I finally discovered bebop and the new jazz as a freshman at Dartmouth in 1952, hearing one afternoon on a Boston radio station the sounds of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, et al. The impact was stunning. Somehow I comprehended what they were doing, and my musical life changed henceforth. I wanted to play piano like Bud Powell.

Weekend trips to New York (and later Chicago, where I was in graduate school) brought me to the music of Miles, Monk, Mingus, Bud, Bird (heard once, on the stand at the Metropole, not playing well), and many other great musicians at a time when jazz was flowering. In 1965 I moved to New York to teach English at NYU and City College. And I became a music critic—first for the New Leader, a small but influential Leftish monthly which had a great arts section. Then I wrote album and concert reviews for Playboy for nine years, which gave me entrée to much of the music scene in New York—rock, classical, and jazz . . . Now we’re finally getting close to Mingus.

Before New York, in 1962 (I think), I was auditioning his new Oh Yeah! album in a listening booth at a Madison, Wisconsin, record store, laughing and digging “Eat That Chicken,” “Hog-Callin’ Blues,” and the rest. After some years of not paying much attention, I finally woke up to the raucous humor and formidable genius of Mingus and Roland Kirk playing together. There has never been a record like Oh Yeah! and never a duo like Mingus and Kirk. I was lucky enough to get to know both of them, and their music changed my life.

Flash forward ten years, when I had left New York but was still writing for Playboy. There was news of an upcoming concert by Mingus, and I convinced Sheldon Wax, the magazine’s managing editor and resident jazz lover, to let me cover it and possibly do a feature article on Mingus, who had recently emerged from a long, sad, and fallow period, during which he had been off-mike to all but a few close friends and associates. There was a story there.

This event was the first Mingus and Friends concert (there were two), and it happened in New York on February 4, 1972. Here’s part of my somewhat overbaked review of the concert, which had aroused a lot of interest in the New York music community.

After much fanfare (e.g., Nat Hentoff’s article in The New York Times) and expectation (this was Mingus’s first concert in ten years), word had gone out that we were to witness a great comeback or another milestone in an already protean career.

Most of the 2800 seats in Lincoln Center’s Philharmonic Hall had been sold and were filled with a crowd, somewhat younger than we had expected, from the obviously higher reaches of hipdom—outlandishly fine chicks, studiously inelegant males, black saints and sinner ladies. They came to hear an 18-piece ensemble featuring Gene Ammons, Bobby Jones, Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan and Milt Hinton—for starters. Bill Cosby strove manfully and entertainingly as emcee. Teo Macero, who looks like a librarian, kept dropping the score but flailed away with the baton, assisted by Mingus from time to time. Dizzy Gillespie, James Moody and Randy Weston made brief appearances during a long jam session later in the program.

. . . More like a rehearsal than a concert, its bright moments came inevitably when the band loosened up from the tight complexities of Mingus’s earliest compositions or the structural requisites of some of the later ones: a classic blues solo by Gene Ammons on tenor, backed up by Mingus, which ended the first part of the concert; a couple of songs by Honey Gordon, who sounds like Duke Ellington’s 1940s vocalist Joya Sherrill and Ella Fitzgerald combined; a piece written for Roy Eldridge and marvelously played by 18-year-old John Faddis on trumpet; and a few of the Mingus standards, such as “E’s Flat Ah’s Flat Too.”

The other good things were segments from the new Mingus album on Columbia, his first in eight years, Let My Children Hear Music. If what we heard of it that night is any indication, Charles is not jiving when he calls it “the best album I have ever made.” Despite incredible setbacks in recent years and a sometimes disappointing concert, one of the great jazzmen of all time is back, making original, vital music again.2

That concert and Children marked a new beginning for Mingus, and they were the initial impetus for this book. When I first met him in 1972, Mingus was finally off the pills and out of the shadows, once again eating with a vengeance, blowing away people with insults, and talking. God, could he talk. I’d been around a lot of jazz people but had never heard anything like it.

In subsequent visits, I got to meet the Mingus family—Charles, Susan Graham Ungaro (not then his wife), arranger Sy Johnson, the musicians in his regular small band (Bobby Jones, Charles McPherson, and others)—many of whom will have something to say herein. I missed out on Dannie Richmond, the one I really should have talked with.

I quit writing about music in the 1980s in part because I could never resolve the critic’s dilemma: you either limit yourself to readers versed in various kinds of technical talk and bore them with musicological maunderings, or you write your impressions. Neither approach alone is sufficient to render the sense of what’s going on in music. On a deeper level, critics and musicians operate in different worlds, even when they intersect, as Julio Cortázar conveyed so well in his roman à clef of Charlie Parker’s last years, “The Pursuer.”3 Unlike most other arts, music dances away when you reach out to it. The Mingus book also kept dancing away from me.

Part of my delay in getting it done at first was preoccupation with an increasingly messy personal life; part was owing to the need to raise a family and earn a living; part was avoidance of a project that I had endowed with a lot of emotional freight.

At one point a few years ago, my intention was to make these materials into a multimedia e-book production (à la Ken Burns but better) that I would self-publish with software like Adobe Acrobat. This would dramatically display Mingus the man, his music, his cohorts and friends, the works. Sy Johnson promised help and some photos; others contributed as well (see the acknowledgments). The New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) graciously sponsored the project in February 2008, and I worked for a year seeking funding.

When that wasn’t forthcoming, I had to reevaluate. The project is now what I had originally conceived it to be—a book of interviews, and that’s a better, much simpler solution, finally.

What Mingus and I did manage to get done was a twenty-hour series of taped interviews in 1972 and 1974 in Philadelphia and New York (see the chronology), an amateur recording of some fine music one night in Philly, and a number of revealing discussions with ten friends and associates, also interviewed by me and included here as chapter commentaries. I’ve placed these commentaries after the Mingus texts in their appropriate settings so as to give readers a different take on what Mingus and I talked about and, frequently, to add detail and perspective to things he brought up. My intention is to add a kind of counterpoint to the Mingus themes.

The interviews were first intended for a feature article, and later, when that miscarried, we continued the talks to develop a book-length publication, “my life in music,” as Mingus put it. Playboy rejected my 1973 article submission; “too much of a fan-magazine tone,” they said. In 1974, five years before he died, Mingus, Sue, and I met and talked with an editor from Doubleday about a book that never went beyond proposal stage. The year before, they had published Ellington’s Music Is My Mistress, and Mingus had also talked for years about a book to cover his musical life—meaning all the stuff and substance that hadn’t been given form in Beneath the Underdog, his 1971 autobiographical fantasy. The fact that Duke, whom Mingus worshipped, had done his “life in music” also must have influenced him. Our book would cover his musical development and progress, the important influences and contacts, his opinions on music and musicians, on life.

Mingus Speaks is not that book, but it provides clear glimpses into these areas, a few more pieces of the Mingus puzzle, and some new explanations as to how that wonderful music came together. There is much material here that has never been revealed before, and a side of Mingus that may come as a surprise to some. With minimal content editing, he talks directly about the subjects that were on his mind in 1972–74, one of his most creative and tumultuous periods.

Yet the technical editing and transcribing difficulties were considerable, given the man’s rapid-fire, slurred manner of speaking. In most of these chapters, I’ve cut and pasted to keep the continuity; the reader will notice breaks in the text where these edits occurred. In other chapters, I decided to let the reader see how Mingus’s mind worked, how one subject flowed into another without much prompting or direct questioning from me, how one association led to another. “Spontaneous composition” is what he called it in music.

There are only select references here to the Mingus literature and to unfamiliar names and events that might elude all but the most knowledgeable jazz person. My headnotes and comments are generally short; in a couple of instances, I’ve written more extended commentaries. The idea is to not distract the reader from Mingus, to amplify and explain only when necessary.4

Mingus allowed me to be his Boswell, I think, because we personally connected on a number of levels. He respected my background as a writer for some years on jazz and concert music, respected that I had been a “professor,” that I worked at the time as a writer for Playboy. That last affiliation appealed both to his sense of humor and, one might say, his prurient interest: “You’d go right down in the heart of Tijuana and we’d go to this restaurant where they had the finest dancers—I mean bad, baby, bad. Playboy’d have trouble with this club. In fact, one broad I could tell I could have her without the money, one of the dancers. They weren’t all whores.”

Playboy had once made Mingus an offer to reprint and distribute some of his music (see chapter 6), which he foolishly rejected. And the magazine in the early 1970s still had considerable mystique in the world of jazz, having sponsored numerous festivals, conducting a highly regarded jazz poll, and booking jazz into its clubs. Playboy was also a somewhat fading though still central rallying point in American culture for promoting sexual freedom and “the good life,” plus providing a forum for quality writing on racial issues and left-wing politics—all stuff that Mingus responded to.

In the interviews, we had conversations about the man’s appetites, his fights and frustrations with Sue, his “extrasensory perceptions,” as an early composition had it, the pains and the pleasures of living. Not to mention the music. The talk, the psychology, and the music were all of a piece with Charles. He was easily the most complex person I had ever met—and one of the most open. There weren’t too many filters operating when Mingus talked, and I’m proud that he trusted me.

NOTES

1. Mezz Mezzrow and Bernard Wolfe, Really the Blues (New York: Random House, 1946).

2. “Acts and Entertainments,” Playboy, May 1972, 24. I did other occasional reviews of Mingus music during my stint at Playboy. My signed obit for Mingus was published in the November 1979 issue, 60–62.

3. In Blow-Up and Other Stories (originally, End of the Game and Other Stories), trans. Paul Blackburn (New York: Pantheon, 1967), 182–247.

4. What Mingus said in these interviews was, of course, his own subjective truth, not always objective fact. Where I felt further explication was necessary, I’ve added chapter endnotes or in-text commentaries.