Читать книгу Mingus Speaks - John Goodman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| 2 | Studying, Teaching, and Earning a Living |

| “Lloyd Reese . . . was more than a genius.” |

I asked Mingus to talk about his first days in New York, when he was married to Celia. A good part of what he had said about that period in Underdog was fiction, and I wanted to hear the true version. He couldn’t make a living by teaching, he said. He got into describing his work at the post office, which led him to the problems of writing music for a living—and how Bach and Beethoven handled that, with some asides about Beethoven’s living style—and finally some musings on the high life and the low life for a musician.

Many of his thoughts on classical music and musicians concentrated on the conditions under which that music was composed and played, the economics of writing and performing it, if you will. There were lots of bons mots here—among them, “the best job [Bach] could get was to write for Christians.” For Mingus, at least in these interviews, it was mostly about how to make a living in music.

• • •

MINGUS: When I first came to New York I was teaching—Percy Heath, then I had Jimmy Garrison, several white students—one of the guys became a big gambler, Italian kid, can’t remember his name now. He went to the horse races and found he could make money that way and quit playing—and he was a very good player. Had them as private students, singly. But that wasn’t enough money.

Anyway, Celia told me in these very words before I got started teaching: when she finds herself getting loose or wanting to go to bed with another man—she said she had been working at living with her [former] husband, John Nielsen, and every day the stairs just got higher and higher. So she came in one day, before I started teaching even. I was practicing, we were living in New York, and I’m getting ready to go to work in the studios—because I didn’t come here just to go to work with Charlie Parker.

She opens the door, and I say, “Hi, how you doin’, baby?”

She says, “Whew, those stairs are getting higher and higher.” And that’s all she said, man.

I said, “Well, I’ll tell you what’s going to happen, baby. I’m going to get me a job, quit playing music.”

She said, “You can’t quit playing music,” but she said it in such a sour way that I knew she wanted me to help her get some money.

I said, “I’m going to work, find a job.” I wanted her to say no, but she didn’t say no.

She said, “All right, if you feel you should do it. What can you do? You can’t do nothing, you’re a bass player.”

GOODMAN: Sounds like my wife, man, about what I do.

MINGUS: “Yes, I can, baby. I can carry mail. ’Cause I’m a stone mail carrier; my father was a mailman.”

So . . . I went to the post office, it was around Christmastime, man, and she was getting tired of the stairways, and I didn’t want no woman cheatin’ on me. So I went to the post office and got signed up for temporary service. I got to carry mail, I think. No, I didn’t, in California I carried mail. In New York, they gave me the bundles and the chutes, that’s all I got to do, the heavy work. I worked my ass off, and I remember the guys who were there permanently used to laugh at me ’cause I’d still be working when they were sitting down eating sandwiches. Not at lunch time: they had breaks, little breaks, coffee breaks.

They said, “Mingus, what are you gonna do? There’s always another sack coming, you can’t win.”

But I stood there every day. I said, “Fuck ’em, man,” and I kept throwing the mail, you know. When the chute packs up, the conveyor belt stops. And they all began to like me because I wanted a permanent job. I was doing their work in a way. But they laughed at me, man. Reason I know I was a winner for the post office, which is not much of a claim, but I would just as soon be in the post office as to be here where I am now. I would rather I had stayed there, and I could have stayed. After Christmas came, I stayed on, all the guys liked me, foreman and everybody. You know who got me to quit? Charlie Parker. [Usually] you only worked about two months and then you’re through with it. I worked three and four months, going over the period. I’m bragging about this, man, ’cause not too many cats can work in the post office.

GOODMAN: I think it’s in the Ross Russell book where he says Bird got Mingus out of the post office.1

MINGUS: Well, he didn’t get me out of the post office, man. You know how I feel about it? I feel like this, man: I don’t know what Bartók or Beethoven did for a living, but they didn’t write music for a living. There’s rumors around from the avant-garde and the collectors of history, like Phil Moore will tell you. But what I heard about Beethoven is that he used to go to a nightclub [sounding a little drunk here] or where musicians would go to hear their music, because in those days they didn’t use their horns, they used their pencils. Said, “Let’s write some counterpoint, let’s write some fugues.”

Bach could be sitting in the corner, you know, not being bothered with the jazz musicians, ’cause he knew he was Bach. But you know there had to be a scene like that. Finally, someone would come up and say, “Well, I wrote the baddest. This is the best.” And they find a judge, and ask Bach to come over. And Bach walk over and say, “Well, I don’t know, I can’t compare, but I’ll write you a fugue.” So, what was he doing for a living? He was walking to church on Sundays to pay his rent, he played in church.

GOODMAN: He had his church position, and that’s what paid his bills—

MINGUS: Well, put that in the book!

GOODMAN: Right, and a guy like Beethoven had his patrons, because the system was a little bit different then. He was writing a symphony for Count So-and-So, and he had to make his living that way. But Bach had a stipend, a regular thing.

MINGUS: He was [subsidized] to one position, put that down. Suppose he ever had a chance to write for some dancers, what would he have written?2

GOODMAN: He did, he wrote dances. They are transcribed and sometimes altered, but you’re right, and it all had to be appropriate for his church position. He was the cantor of Leipzig, for Christ’s sake.

MINGUS: Put that in, make me sound intelligent.

GOODMAN: I will [laughs], I’ll try—I mean I’m not that intelligent!

MINGUS: Phil Moore made the classical guys relate to me the same as the jazz guys did. So, fuck it, if Bach was a guy who went to church, the best job he could get was to write for Christians [laughter about this]. . . .

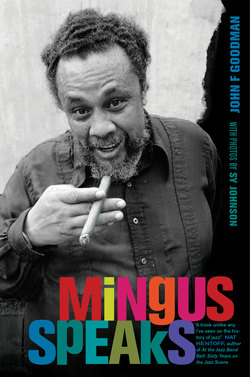

FIGURE 2. Mingus, Sue Graham, Alvin Ailey (at end of row), and dancers rehearsing “The Mingus Dances,” 1971. Photo by Sy Johnson.

GOODMAN: Want to get out of here?

MINGUS: No, not done in here, I ordered a hamburger. My friends are bringing you and me some fine smoked Nova Scotia salmon and bagels. Well, that’s like about nine-thirty or ten, so that’ll be our little snack, you know. . . .

Phil and Red [Callender], they knew the history of music, but they’re musicians. But I never saw ’em, I never went to school, I went to a private school. They were more concerned with the fundamentals than with what Bach did. They would play Bach for you, the music, and write it for you. But listening to it was for guys like you and me.

Beethoven used to shit in his house, in the corner. Did you know this? You can read that.

GOODMAN: Sure, I’ve read it, but I don’t necessarily believe it.

MINGUS: But it’s possible to read, right, that he lived like an animal? That’s what I read.

GOODMAN: Yeah, he was a piggy guy, and we know that.

MINGUS: Well, so am I, man, you should see my apartment, that’s why I’m gonna take you there. You ever see it?

GOODMAN: Sure, you took me there once. Fuck it, who cares?

MINGUS: I can’t help it, man. If I were so organized to put things on shelves, I couldn’t find nothing.

GOODMAN: I once wrote a column about a writer who criticized Beethoven for his “slovenly habits”—that he lived like a pig, you know, and was a terrible person. He insulted and was rotten to everybody. And all these books about Beethoven and how impossible a guy he was—that is the worst kind of music writing.

I mean, if he hadn’t written the greatest music in the world, would anyone have cared one good fuck whether he lived like a pig or like a king?

MINGUS: Well, you know pigs are very important, you know, you eat pigs. So if you live like a pig, you don’t bother me, man.

GOODMAN: It’s irrelevant and dumb.

MINGUS: We should talk about it though, man, we should talk about it in a different way. I think that this showed that the man wasn’t making any money. That’s what I was talking about. The fact that he had to live the same way as I live.

Everybody in the band gets $450 a week; I’m making $2,500, and I pay the agent, the plane fare, expenses—I don’t make nothing, man. It’s like doing it for kicks. And I can’t go on for kicks anymore. That’s why I’m writing this book. That’s why you’re going to write a good book. That’s why I can’t fuck around. [Pause.] You got to go inside my head and take out all the cobwebs and take out all the real things and all the bad things. I think you can do it, man.

GOODMAN: I hope so.

MINGUS: Well with the Playboy thing, I thought we could do it.

GOODMAN: I’m glad you think that, and I’m happy because I think we can do it.

MINGUS: Why don’t you talk about some things that bug you? You should talk about the fact that people write criticisms on Beethoven that talk about him living as a pig. We should talk about it, and the fact is that maybe he did, and maybe a pig’s life ain’t so bad, man. Maybe he was so busy with what he was doing—

GOODMAN: Obviously, right. You know, Sue said something to me the other night: “If only Charles had gotten that nice studio overlooking the river, he could have gotten rid of that lousy apartment he’s got.”

I said nothing but I thought, well, if he really wanted to get out of that apartment he’d get out of there, and why should he have to get out of there? It doesn’t mean anything. I live in a very nice house, and I’m thinking of getting out of that.

MINGUS: This is good material, man. I’ve lived on Park Avenue, 1160, I lived in one of the best houses they have for white folks. I had to send a white man in to get the apartment for me. They wouldn’t rent it to me. Sent in a guy who said his name was Mingus, introduced himself and got the apartment for me. And I’ve lived in Harlem, the best apartments in Harlem—which are just as good as the best apartments on Fifth Avenue. And I wrote the same kind of music, but I still haven’t written the music I want to write. It’s weird.

I’m still playing jazz, on the bandstand, in pigpens—’cause Max’s Kansas City is a pigpen—still playing with people, one of these days, ding-ding-ding-ding, I’m gonna get a chance to write some music, ding-ding-ding-ding, ’cause you can’t work in these clubs like this, ding-ding-ding-ding, with Dannie Richmond and these kids who don’t even believe in what I believe in. You can’t write a composition of what you are, you can’t even improvise a composition of what you are and play it in these kind of places. And play this often. And travel in the airplane, travel on the train, travel on the bus. You can’t do this, man. This is tougher than Beethoven had to do, man.

GOODMAN: Yes, it is. He could sit on his ass.

MINGUS: He had no travel problem. That’s what I’m saying. If Beethoven had been a garbage man and wrote the way he wrote, if somebody could hear what he’s doing and say, “Here’s a guy who wrote beautiful music, more than beautiful music, he wrote real music, pertaining to his society completely, wrote music pertaining to the hereafter.” [Chuckles.] He had a hell of a belief—he had more of a belief than Bach. I don’t notice in any of Bach’s writing any fact for a moment where he believes in Jesus. Yet in Beethoven’s music, I hear where he might have believed in Jesus, and he never wrote for church.

GOODMAN: I’d argue with you on that, but it’s another discussion.

MINGUS: Well, the way they play it, man, the counterpoint or fugues, on piano especially, I’m talking about piano music, Bach on piano, I can’t hear no more where he believes.

GOODMAN: But Bach on piano is not the real thing, you know.

MINGUS: I’m glad you’re here, man. . . .

• • •

In discussing classical influences and how Mingus used them, we rambled and zigzagged as usual. His talk started with how he used music to seduce women—writing string quartets for them—and, after some excursions, finished again with that theme. Mingus’s string quartets were known only to a relative few, and I never got to hear them.

The most obvious example of classical influence in his music is “Adagio ma non troppo” from Children, which, as Mingus says below, uses classical forms and procedures to highlight jazz improvisation. It is the most obvious recorded bow to classical sources and forms he ever wrote, though “The Chill of Death” from the same album clearly owes something to Richard Strauss.

Symphonic suggestions are sometimes woven into his other work—obbligato parts and voicings in the big band music particularly—yet the result is nothing like Third Stream music. What he did learn from the classicists was how to use tone color. But I don’t hear much in the way of “classical,” neither concert analogues nor direct borrowings, in Mingus. When he says he “always wanted to play classical music,” I think he means music with that depth, structure, and complexity. When he talked with the Italian interviewer (see Introduction), he said he was waiting for the chance to write, not Western concert music, but “classical, pure, serious music that came out of all the musics.” Mingus the composer was a synthesizer, a true eclectic, one who totally integrated those multiple sources into his music.

As Alex Ross has pointed out, the compositions of Mingus, John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman expanded the tonalities of bebop, and as composers they had “much in common” (well, something in common) with Stravinsky, Debussy, and Messiaen.3 Along with the music of Ravel, the music of these composers was in the air, and many jazz musicians were listening. They wanted to be taken as serious musicians.

Yet here’s a guy who loves the “bitches” and is desperate to get laid, while at the same time he’s at the piano “improvising in symphonic form”! I took that as some kind of epitome of Mingus.

• • •

MINGUS: It’s funny, man, I know the name Mary Campbell [see chapter 11] means something to you now—Campbell’s soup maybe, and she told me about that later—but before she told me about it I was still in love. When I looked at her I just forgot all about the bitches I looked at at home base. I figured this broad had been in some kind of church and knew classical music. I had some classical repertoire. She asked was I trained in school and all that, and—Lloyd Reese never taught me this, I was born with this—I used to improvise in symphony [form]. I got proof of that, a composition on Columbia, an improvised thing in Let My Children Hear Music, one of the tunes in there, “Adagio ma non troppo.”

GOODMAN: Are those tunes that early in your life?

MINGUS: That kind of playing was.

GOODMAN: “Half-Mast Inhibition,” that wasn’t an improvised piece?

MINGUS: No, that was partly jazz too. But the basis of my playing was always the desire to get over the music I was playing, to make enough money to play the music that I wanted to play. I always wanted to play classical music—not Beethoven or Bach or Brahms, but improvise and compose new string quartets. Like I had a string quartet to do—I hate to jump fifty years on you—for the Whitney Museum.

I didn’t write [the quartet] out, I composed it on piano. But when people heard the composition, they thought I had spent months writing it. I played it on my piano. I reveal this in my book. And it was not for critics, because I played it at Newport. Most people picture me in there writing, taking time, because it takes six months to write a string quartet with all the bowings in it.

GOODMAN: I remember when I last saw you [in 1972] you were writing them. You had done two.

MINGUS: Well, I did one with the pencil and never finished it. I have sketches for about four more that [unintelligible]. I only have the copy of the one of ’em here, the one I did already, six-seven minutes.

GOODMAN: Did you perform the other? Kermit Moore was going to play it.

MINGUS: Yeah, Kermit Moore played it, and he also did it in Newport.

GOODMAN: Who else played? I wish I’d heard that, goddammit.

MINGUS: I wish you’d heard it too, man.

GOODMAN: Matter of fact, George Wein is the guy who said “[Whistle], Mingus’s quartets—I never heard anything like them.”

MINGUS: Yeah, well, don’t tell him yet. Don’t tell him till the book comes out. He doesn’t know about my writing them on piano, he thinks it’s a [composed,] written-out thing.

GOODMAN: You transcribed it, then?

MINGUS: Same as you and I are doing now. But the one I did with a pencil, I could see myself cutting the writing I did on the piano. Started one on the piano, it was one of the poems, poems for that guy, a whole concert was for him, at the Whitney Museum. Sue told you about it—the guy that got killed on the beach at Fire Island, a poet.4 Funny I don’t know the name.

That’s one thing I did write down and memorize, though: the word part, the slurring, legato thing that went through the melody that the cello and violins and all were playing. I sang that, didn’t play it, couldn’t play it [sings it]—those kind of sighing things, like in Hindemith, Bartók—Bartók, the theory was Bartók.

As a kid I was always very gifted in hearing something done by a classical composer and then going to the piano in the middle of it and just playing it. I don’t have perfect pitch either. This [would be] after the record [was] off, and I’d say, “I know what that is” [sings a phrase]. Red Norvo, I did it once for him, they were playing, umm, some difficult composer, a Spanish composer—know any?

GOODMAN: Albeniz, Villa-Lobos—

MINGUS: Villa-Lobos, they were playing Villa-Lobos at this house, and I was with Red Norvo then—this was many years later—and they said it was quarter tones, a quarter-tone piece. So I told Red, “This isn’t quarter tones; I can show you it’s not.”

Well, his attitude was, “Go away, boy,” you know.

And so when the concert was over with, I didn’t say nothing. So fuck it, I just went to the piano and did [sings melody phrase] and I played every note that every instrument was playing—not too long, I couldn’t play the whole piece.

They said, “How’d you do that? How’d you do that? You got perfect pitch?”

No, I haven’t got perfect pitch, man, and that’s not quarter tones. If it was quarter tones, I couldn’t have played it on the piano. That shows how the public can be fooled. They put on [the album description] that it’s a quarter-tone piece done by so-and-so, and the poor public buys it, and it ain’t quarter tone.

GOODMAN: And if the public can be fooled, you know damn well that musicians can be fooled too. Red Norvo is a good musician, and he got fooled.

MINGUS: Sure, musicians can be fooled, sadly. Red got fooled. Tal Farlow’s a guy who’s got perfect pitch, and he got fooled.

GOODMAN: Chuck Wayne was the guy I was trying to think of the other night when we were talking—

MINGUS: Bad man!—the one who was playing with the other guitar player at Bradley’s?

GOODMAN: Double session, yeah, he’s awful good, goddammit . . . So let’s talk about Stravinsky and Bartók and all those people—

MINGUS: That’s where we are now.

GOODMAN: Very honestly, I don’t hear a hell of a lot of that in your music, but I know that they are important to you and that you’ve been involved in a listening way.

MINGUS: It’s funny. I was talking to a piano player, Tommy Flanagan, in Copenhagen—he’s with Ella Fitzgerald—and we were talking about Coleman Hawkins, and so I was telling about how great his library, record collection, was; he had records all over the house. Flanagan said he didn’t have no jazz. All he had was Beethoven, Bach, Brahms, Stravinsky, Bartók. He’d try and play Bartók in the middle of “Body and Soul”—and this cat knows.

We had a whole discussion about piano players, because I love piano players, good piano players. So I made him go to the piano and play the changes to “Body and Soul,” and a couple of things that guys don’t do any more. He says, “Hawk would take and play this against E-flat, Mingus. Wasn’t he crazy? That’s called ‘Clair de Lune.’ ”

GOODMAN: Same intervals, you mean?

MINGUS: Same intervals but not in the same key. You’d think he’d play in the original key he’d get off the record.

GOODMAN: Well, that’s the kind of thing Debussy did too, you know. So Tommy Flanagan heard that?

MINGUS: Well, he’s a musicologist. I was so embarrassed, man, he knows so much music, listening music. We were sitting in a nightclub, and they played some music [on record] with Bird on tenor, and he knew who all the guys were—Sonny Rollins and Bird. He said, “Sonny Rollins didn’t play good here, he played wrong.”

And that’s what a musicologist is, because Tommy Flanagan is something else. He said, “This cat missed. Bird fucked him up.” That’s on Prestige, I guess, eh?

GOODMAN: Yeah, I have it, it’s a great record.5

• • •

MINGUS: The way I feel now is I should be having some students over at my place. But I’ve still got to work until that day comes when I can build a school and get some students to play some real music.

GOODMAN: And an audience that knows you. Like what classical music is doing, but they are in hard times too.

MINGUS: Kids should be educated to music, man; [classical is] not bad music. Our society should be listening to operas and everything else by now. It’s just noise to them, they can’t relax for a minute, it makes them sick. If a guy came in and played a beautiful violin for two-three minutes, they’d go crazy—over an ordinary microphone or no microphone.

Don’t you think they could appreciate Pablo Casals if he was young today? Sure they could, man, if this damn country would push it. I don’t know why they don’t want the kids to hear good music. Is it because it would make them healthy? They might throw their pot away. They might, man. You going to print that? And the young Casalses, they’re stopping them.

GOODMAN: The conservatories and the system for making it in classical music is hard, it’s a hard apprenticeship. But they’re still playing the same old Beethoven’s Third Symphony for the same old ladies in fur coats.

MINGUS: What about classical modern composers? There are some good ones. We had a guy named David Broekman that to me was great as anybody who ever lived.6 But they killed him. I heard his symphony, an unaccompanied cello concerto, no comparison, and he knew he was a master. He first played down in the East Village, Third Ave. and St. Mark’s—what’s that place? across from the Five Spot [Cooper Union].

David Broekman, I used to study with him. He used to come to all our concerts. Teo had a thing called Composers Workshop with Teddy Charles, John LaPorta, George Barrow, a blind bass player.7 You know, they used to call us avant-garde, and if you listened to the stuff [we were doing then] it was more advanced than what they’re doing today. Yeah, I hate to say it that way, but we were really experimenting and trying to do it right. We weren’t bullshitting. And it’s much more complex, more advanced. I did one back then—used Teo and John LaPorta—and that wasn’t even modern, I wrote that one in the ’40s. More complex as far as the bass is concerned.

David used to come to our concerts, and Henry Brant—someone else, a classical composer—they came a lot because Teo was there, but they were enjoying more than just Teo, because they came more than once. David was prematurely gray, and I went and talked with him. He said, “You’re a composer. I can teach you how—instead of putting twenty notes down, you take seven and do the same thing with it.”

I said, “That’s what I’m looking for, I’ll be over.” And he would take a run of notes [demonstrates] and pick out the ones that were important. Find the melody that was really in your mind. The excitement could come from the percussion [demonstrates]. How to orchestrate for full orchestra, get more out of what you’re doing. He didn’t say “never do that,” but the whole composition was [demonstrates]—no breaths, like right off the piano. I seen my piano player now [John Foster]—since the concert he told Sue he’s gonna write four compositions every day! Yeah, but he hasn’t got one rest in his tunes! Man, he needs sixteen rests. Something else he hasn’t got is syncopation, and that’s what jazz is.

People think jazz is just playing the melody. Charlie Parker cut everybody; Charlie Parker invented new rhythms, just like a tap dancer. All the time he was playing not only melody but rhythm patterns. That’s what those [young] guys are not doin’, man. They just copy his riffs, and when [Bird died], that was it—they just end up playing a few riffs. But the guys that know, a few of ’em could go on, and, uhh . . . well, see, I want McPherson to do more than play bebop. He learned a lot but still has to invent more than that.

If Bird were here today, he wouldn’t be still playing bebop. You think he’d let Albert Ayler or somebody like that cut him? He’d do the squeek-squawk too but only a few bars of it. He wouldn’t do every tune like that. He would be avant-garde at the end of the composition or in the middle as a laugh and then go back to playing the music.

You don’t just eliminate the beat. Music is everything—the beat and the no-beat; jazz wants to beat, emphasize the beat, so you don’t cancel it entirely. Especially if you call yourself black, because African people ain’t gonna never stop dancing. Puerto Ricans, the gypsies, Hungarians, they all have a dance music. You know? But they also have mood music that don’t have a beat to it sometimes; Indian [music] don’t have a beat to it, but when they dance to it, they got a beat to it. I don’t see why these cats are ashamed to have a beat to their music.

GOODMAN: Tell me about Lloyd Reese, Charles. You said Eric [Dolphy] studied with him?

MINGUS: Yeah, I studied with him, Buddy Collette studied with him, Harry Carney used to go to him for clarinet and bass clarinet. He’s a well-learned man. If you say genius, well, everybody says genius, but he’s a man who did 90 percent work and got the results. Or he might have done 100 percent because he was above the average genius, more than a genius. He played and taught piano, played all the woodwinds, all the reeds, and trumpet.

Lloyd was in a guy named Les Hite’s band, and somebody in either the saxophone section or the trumpet section died. [Lloyd] was the first alto player, right? And they kept finding trumpet players to take the man’s place who died, and they never liked them. So Lloyd told Les Hite, “Hire Marshall Royal to take my place, and I’ll take off and learn the trumpet, because your trumpet’s not right.”

That’s how he became a genius—went and studied the brass, came back, took his job back and was considered the greatest first-chair man going in that period—in the late ’20s. Les Hite’s band came after Fes Williams’s famous band, but Les’s band lasted even up to Duke Ellington and was one of the greatest jazz bands ever heard, man. Snooky Young played in that band, but later; plus some guys you know.

Lloyd was just an unbelievable player, man. He played so much trumpet at jam sessions that nobody thought he was playing anything. Crazy [demonstrates with lots of notes, runs]—like a flute or something. I don’t know how to explain it to you, man. And the man knew what he was doing. I’ll tell you how bad he was: at the musician’s union they had some helluva musicians who everybody respected, and I forget what the question was, but somebody put a bet, a lot of money on it: “The book says so-and-so.”

“But that’s that book. This book says so-and-so.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what, man. Call Lloyd. Do you respect Lloyd Reese?”

All the students said, “Yeah, we respect him, man, let’s call him on the phone.”

So Lloyd came over and said, “I have no favorites here, guys, but this is the answer.” And he said neither was right, and they all took their money back.

He did have a rehearsal band though, because we all read [music]. He gave us the inner thing, and he’d make us change instruments. Gave me trumpet or something. I don’t know why he always gave me trumpet, but then he’d show you how to set harmony, how to make up tunes with a big band—without [written] music—by someone starting the melody in one of the sections and by the time the reeds set their five-part harmony to it—mainly the blues, you start with—then the brass would take the same melody and harmonize to it, then the ’bones would take the same melody. By the time each section’s played the melody, then somebody else figured out a reed riff or an organ point to play behind ’em.

In fact, Lloyd said there was a day when he used to go to work with no [written] music at all. Just hear a tune, play it, the brass got it, and [they’d] open the chorus. I know a guy who played in a band like that, but he used to talk like it was a lot of fun. People had music stands sitting there, and nobody had any music—played the latest tune, everybody making the harmony up. Or [Lloyd would] bring blank paper, and he used to write down: “You’re in B-flat”; “you got G”; “you got A,” you know. [He’d assign parts] and we’d play it and it’d be unbelievable. But he wouldn’t use no score.

Great trumpet player, great teacher. And some of his students, man. A guy like Harry Carney with Duke and playing as good as he plays now, as good as he was then, tells you something’s going on.

GOODMAN: It reminds me of what I heard about the Duke—teaching without a fixed score.

MINGUS: Then writing stuff down on paper.

GOODMAN: But there are no more teachers like that—or do you know of any?

MINGUS: Well, there was gonna be some. Buddy Collette was gonna come down here and I was gonna build my school. Berklee and those places, they’re teaching jazz, eh?

GOODMAN: Yeah, what do you think about that?

MINGUS: Ah, the white guys got enough things. Why don’t they let me build my school, let some guys who have been into it do it, you know? I’m not saying guys like Boots Monselli [Mussulli?] shouldn’t do it, ’cause he’s a jazz player, or John LaPorta. But some of the teachers they’ve got can’t even play, man.

GOODMAN: Is that so? I thought they had all jazz people on that faculty.

MINGUS: Oh yeah? Well, maybe it’s the way they approached me. I never heard him blow, but a guy comes in and says to me, “Me, I never really dug your music, you know. Why don’t you come up to school and show us what you’re doing?”

I said, “Motherfucker, if you don’t know what I’m doing by now, why don’t you come to work in the Jazz Workshop, show me what you doin’? If you’re so great, why don’t you get yourself a job as a jazz musician?” Like, I got here the hard way. “Show him what I’m doin’!”

GOODMAN: That’s marvelous. You should audition for them, right? . . .

NOTES

1. No, it wasn’t in the Ross Russell book, which is all the same a fascinating, flawed biography of Parker: Bird Lives! The High Life and Hard Times of Charlie (Yardbird) Parker (New York: Charterhouse, 1973). Russell was a postwar jazz producer and founder of Dial Records. My source here was likely the remarks Mingus himself made in Robert George Reisner’s Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker (New York: Bonanza Books, 1962), 151: “One night I get a phone call from Parker: ‘Mingus, what are you doing working in the post office? A man of your artistic stature? Come with me.’ I told him I was making good money. He offered me $150 a week, and I accepted.”

2. Mingus collaborated with the Joffrey Ballet to create music for “The Mingus Dances” in 1971, choreographed by Alvin Ailey and performed at New York’s City Center (see figure 2). Mingus explored music for dance in many compositions—from “Ysabel’s Table Dance” in Tijuana Moods (1957) to what he called “ethnic folk-dance music” in The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady (1963) and as late as Cumbia & Jazz Fusion (1976).

3. Alex Ross, The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (New York: Picador, 2008), 519.

4. The poet was Frank O’Hara, and the Whitney had commissioned a competition to commemorate him. See Gene Santoro, Myself When I Am Real: The Life and Music of Charles Mingus (New York: Oxford, 2000), 308.

5. Miles Davis, Collectors’ Items, with Miles in two sessions (1953, 1956), the first of which includes Sonny Rollins, “Charlie Chan” (Bird’s recording alias), Walter Bishop, Percy Heath, and Philly Joe Jones, Prestige LP 7044. Parker is not in the second session.

6. A noted Hollywood film composer, classically educated in The Hague, Broekman became prominent for his film scores in the 1930s and 1940s—among them, All Quiet on the Western Front and The Phantom of the Opera. Before his death in 1958, Broekman was quite involved with jazz and conducted Teddy Charles’s “Word from Bird” in Holland in 1956, with the composer performing. See “David Broekman Revival,” YouTube video, from a Nov. 6, 2008, performance, posted by “doeszicht,” Nov. 7, 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=xCoJEbOMtmk.

7. Teddy Charles, one of Mingus’s closest accomplices (see chapter 11) and fellow musicians died April 16, 2012, on Long Island, age 84. See Tim Kelly, “North Fork Jazz Great Teddy Charles Dead at 84,” Shelter Island Reporter, April 18, 2012, http://shelterislandreporter.timesreview.com/2012/04/15388/north-fork-jazz-great-teddycharles-dead-at-84/.