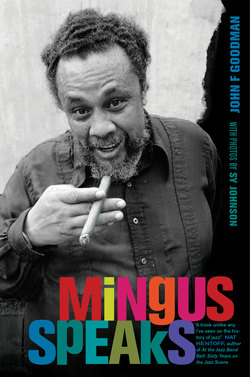

Читать книгу Mingus Speaks - John Goodman - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| 1 | Avant-Garde and Tradition |

| “Bach is how buildings got taller. It’s how we got to the moon.” |

The history of the jazz avant-garde is interesting, even if the music frequently is not. Could a white person have any business writing that history? Or even understanding the music? That’s the kind of question that was being asked in the late 1960s.

I didn’t form my opinions on this music based on what Mingus had to say; I came to them after a long period of trying to be sympathetic to the widely advertised intentions, protests, and sounds of much so-called free jazz. One of the problems I had, as our conversations demonstrate, was trying to separate the apparatus of protest from the concerns of music.

Mingus always claimed to play “American music,” and yet his idea of creating a music to appeal to the spiritual and cultural needs of black people, a revitalized ethnic blues, is an old one in jazz, though not widely recognized.1 The free-jazzers wanted that too, and Cecil Taylor, for one, tried to bring music to the black masses. Still, it is hard to imagine a worse way to reach large numbers of people than through avant-garde free jazz. Mingus at least thought a broad-based blues might be the answer.

He also brought politics overtly into his music, which generally worked because the politics were subordinated to the musical concerns. Avant-garde jazz came alive in the ’60s as part of so much other political protest, of course, and was a response to that political environment, the rise of rock and roll, the growing exclusion of jazz by the record industry, the diminishing jazz audience, the entrance of jazz into the academy, and more.

Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) has been a great champion of the avant-garde, and his writings in Blues People (1963) and later in Black Music (1967), a mixed bag of essays, reviews, and notes, frequently get close to the essence of the New Thing and its people. Yes, there is a lot of “Crow Jim” in Baraka, but he knew the music, its players, their aims—and he was black. Finally, a literate black jazz critic spoke out—going beyond Ralph Ellison, one might say.

It’s difficult to read the old Baraka/Jones today, at least for me, because of the ethnic venom that took him over for a long time. It’s also hard to make that jump back into a period when art was so deeply politicized, in every sense of that term. Politics and art have never merged easily and have frequently failed, as they did in the New Thing, to merge at all. The Africanism in much of that music was often just an overlay, and it was simply not cool to stress the importance of training and tradition: that was too Western, too white, too Brubeck.

Not everyone saw it that way, of course. Time magazine in a basically sympathetic 1962 piece entitled “Music: Crow Jim,” begins by reporting Mingus’s angry threat to leave the United States forever (for Majorca).2 The article concludes by quoting Cecil Taylor on the destructive effects of this kind of prejudice: “Noting that modern jazz owes much to the European classical tradition, pianist Taylor points out: ‘Crow Jim is a state of affairs which must be remedied; jazz can never again be music by Negroes strictly for Negroes any more than the Negroes themselves can return to the attitudes and emotional responses which prevailed when this was true.’ ”3

A 1958 piece by Kenneth Rexroth, one of jazz’s best and least-acknowledged critics, predates this observation and presents “Some Thoughts on Jazz as Music, as Revolt, as Mystique” with references to Mingus (whom Rexroth knew well) throughout. I don’t know of a more interesting, quirky, “I’ve been there” approach to these subjects.4

Regarding jazz as protest, Rexroth says, “The sources of jazz [as dance music] are influenced by racial and social conflict, but jazz itself appears first as part of the entertainment business, and the enraged proletariat do not frequent night clubs or cabarets.”

Many members of the New Thing scorned the entertainment and business side of jazz. But trying to be “relevant” while making a living playing any kind of jazz in the 1970s was a serious and growing quandary. That’s the context in which Mingus and I spoke.

• • •

GOODMAN: The people most involved in this free jazz, like Archie Shepp—do you think they’re trying to con the white folks or that they conned themselves in this thing?

MINGUS: I don’t know about using their names, but I think what has happened is that they’re trying to cut Bird, to say this is a new movement. But you don’t take an inferior product and say that this is better than Vaseline. Everybody knows it’s not—everybody who’s listened seriously to the other thing. “This isn’t Vaseline; it’s got water in it.” They may be serious, but their seriousness hasn’t gotten through to me yet.

Everybody’s got ego, and everybody who lives in a human body thinks they’re better than another guy. Even if a guy’s considered to be a nigger in the South and the white man says he’s better, if the guy’s on his own and creating, he says, “Man, I’m better than that guy.” I got a tenor player (I won’t call his name), wanted to be in my band a long time, and he can’t play. But when the people see him, he’s moving like Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane at the same time, and man, they clap, and he ain’t played shit. And so I know that he feels, “Hey look, Mingus, I moved the people, you saw that. Why don’t you hire me?”

I try to explain, “Well, I don’t move no people like that, man; that’s not what I’m here to do. I guess I could kick my leg up too, spin my bass,” and he don’t believe me so I do it, do the Dixieland, spin the bass and they clap. I mean that’s showmanship, but this is supposed to be art. I mean the only time they Uncle Tom in classical is when they bow, you know those classic bows, the way they had, man? Especially the women, opera singers, that crazy bow [curtsy] when they get down to their knees? They had some class.

You know, anybody can bullshit—excuse my expression—and most avant-garde people are bullshitting. But Charlie Parker didn’t bullshit. He played beautiful music within those structured chords. He was a composer, man, that was a composer. It’s like Bach. Bach is still the most difficult music written, fugues and all. Stravinsky is nice, but Bach is how buildings got taller. It’s how we got to the moon, through Bach, through that kind of mind that made that music up. That’s the most progressive mind. It didn’t take primitive minds or religious minds to build buildings. They tend to go on luck and feeling and emotion and goof. (They also led us to sell goof.)

It’s very difficult to play in structures and play in different keys. When a guy tells you all keys are alike, he’s a liar. If so, give him a pedal point in B-natural or F-sharp or A-natural and see what he does. Even if he’s playing another instrument like the alto saxophone (which if you’re in the key of C it puts you in A-minor anyway), if you put him in A, he’s in F-sharp; if you put him in B, he’s in G-sharp. So he’s hung while you look at him. Guys like McPherson who play bebop are the best; they can run right through the changes.

I don’t do anything hard, just play the blues, and to see these guys turn . . . With Shafi Hadi we played five choruses; we modulated the second one to the key of F (in the “Song for Eric”), we then went to B-natural—and he stayed right in F all the way out. He never even heard the fact that we modulated. Then the trombone player finally came in, in the right key. That goes to show you how even musicians don’t listen. Here’s a guy paralyzed to realize something’s wrong with the bass notes: he stayed right in the key of F. It was like going wrong down a one-way street and you don’t even see the cars coming. It was pitiful.

And it wasn’t only Shafi Hadi. Eddie Preston soloed and stayed in the same key. He finally caught himself after three or four choruses. You can tell when the piano player and I were doing it for fifteen-twenty minutes, changing keys all over the place, and finally the guy came in, in the key the tune was written in, a blues in F. But by then we had gone to B-natural and chromatics.

There are some famous avant-garde guys playing only in C-natural, man, and it’s very sad that Bud Powell played in F all the time. I remember him playing in D-flat once and B-flat, but the key he always chose was F. If he played in bands, the tunes Bird played, he played ’em, but if he chose it was always in F.

GOODMAN: When I interviewed Teo Macero [Mingus’s friend and producer of Let My Children Hear Music] a few days ago, he was moaning about Ornette Coleman, saying just what you did, that he couldn’t play a straight chorus if he had to.

MINGUS: He couldn’t, man. It would be pitiful if he was forced into a jam session and somebody called “Body and Soul.” He couldn’t make it, man. When we played the Protest Festival some years ago at Newport [1960], we played “All the Things You Are,” and Ornette was lost after the first eight bars. It’s OK to play avant-garde and say, “I meant to get lost,” but Max Roach clearly said, “Let’s do something simple like the blues or ‘All the Things You Are.’ ” He couldn’t even play the melody, man.5

But if a test comes by, man, to say, “I’m a jazz musician,” you should be able to play the blues, or “All the Things You Are,” or “Sweet Lorraine.” I got a son named Eugene, and all over Europe, man, he said, “Boy, can I play the piano!” So people thought he was a piano player. And he could play a little bit, he’s got talent enough to go where his ears tell him to go, but then he starts picking up other instruments, flutes and things. Now if someone tells me my son can play the flute, saxophone, bass—he’s plucking the bass too—so if he got famous, man, I’d have to tell you something is wrong, somebody’s fooling somebody.

I got in a fight with my piano player [Don Pullen] about Art Tatum. I said that Art Tatum was the world’s greatest. I was going to say Bud Powell too, but I said he’d never be cut, man. He said, “Why do you want to tell me that? I never heard of Art Tatum.” He’s never heard of Art Tatum? How could a guy play piano and never hear of Art Tatum? Look him up! Art Tatum can play with his left hand what most of the kids today do with their right and left. And don’t mention Bud Powell—he’s creatin’ every moment.

And I heard a record where Ornette tried to play some [familiar] tunes. You hear that one? He played some melodies, but it was like a lot of kids who try to play Charlie Parker: he never made it. Once when I heard him play in California, I got to understand him better. See, when you play without a piano, you can sound avant-garde up front, ’cause a piano boxes you in. Unless you got a piano player who’s gonna play like Monk does—everything in a minor key. Monk is smart; he doesn’t block you in.

Ornette had a piano with him, and he sounded like a poor man’s Charlie Parker. I couldn’t believe it, that this is the same guy everybody was saying was so creative. Very strange. I think that he’d be a hell of a musician if he’d continue to study the alto. He may be a lucky composer. That may be his natural thing, ’cause I don’t know anything bad about his writing.

GOODMAN: The first records he made—for Atlantic, I think—were kind of exciting to me.

MINGUS: For his own good he should try to learn from his own solos off the record, play them back. The other guy, Albert Ayler, [does a flutter-tongue trill] and those guys: let those guys try to play one of their solos back. They’ll make up a new one every time. It’s sick, man, it’s sick shit. You can bullshit some people, but see, they came in and said, “Let’s see how far out you are, we can make a living like this!” But they can’t enjoy doing that, man. It’s impossible to enjoy that.

You want to hear some of that music? Get me and Clark Terry and some guys who know music to play like that and put ’em on. Nesuhi Ertegun was talking to me about doing an avant-garde date with some guys who can really play.6 I called Clark and he said, “Baby, let me get at it.” That would upset those guys, because he can play to begin with, and if he decided not to play he would unplay playing [laughter]. I want to get with Clark and make an avant-garde record. And Teo Macero.

Take John Coltrane: he went back to Indian-type pedal point music, but he got in a streak [rut]. Why couldn’t he do other things too? Why do guys have to stylize themselves? Don’t they know that in the summertime you wear thin clothes and straw hats and in the wintertime, you know, you got a right to play a different tune? You don’t have to be stylized. A preacher preaches a different sermon each Sunday. He don’t preach the same one. They turn a different page, and I’m turning pages all the time because I have a special page I want to get to and if I’d thrown that page open many years ago, I’d have never even got this far.

‘Cause it’s very way out, man: it’ll make the weird guys sound like babies, make men sound like girls [laughter]—at least some men. No, baby, I been waiting to do this for a long time, man, it has to do with three-four keys at once, atonal, whatever you want to call it. But I couldn’t just lay it on everybody at once, because the musicians have to read and improvise at the same time. I had to train the guys to improvise; I’ve got a few of ’em now. I’ll be able to inject ’em into a reading band, and when I get that thing going, you’ll see.

GOODMAN: You’re going to start that in the Mercer [Arts Center] band, or what?

MINGUS: Well, you heard a little of it on this last date [Children], ’cause I used improvisation in all my writing on the record, like on “Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife,” where I overdubbed the solo. Now on “The Clown,” I couldn’t have written that and had the guys do it right, so I had them overdub it. But I knew before recording that I was gonna do that.

I had two spots in there that definitely make fun of the avant-garde musicians. If you listen, you’ll hear McPherson and [Lonnie] Hillyer playing Charlie Parker, and then at the end of the “Fisherman’s Wife,” you hear Ornette Coleman, played by Teo Macero, and then playing all over, this beautiful alto sax, just like Bird, but McPherson’s tone cut everything they were doing. Teo got [the rest] so soft you gotta listen for it. But the idea is that with all this noise going on, here’s this guy playing music and going to good notes behind or against this bass melody [demonstrates], and [McPherson], he’s playing pure honesty, not saying, “Look at me, I’m a king” or “I’m better than you.” Just doing his best he can, like Bird did through the changes, and it’s beautiful, man. [Pause.] This tenor player I got yesterday [Bobby Brown] got a helluva sound too, man.

It’s a drag to have to put down people. But I’ve always known there’s something else to learn, and I really found out what it was just recently when I started saying: “Wait a minute, man, I used to play with Art Tatum, and he used to say, ‘ “Body and Soul,” Mingus.’ ” Or he wouldn’t say nothing; he’d just start and I’d come in in the key of D-flat. And all of a sudden here’s a guy starting on D minor and I’m used to playing E-flat minor. Or some night he’d come in and play in C minor. And I got all hung up on the chords and positions. He’d say, “I’m in the key of B, man, come on, let’s go.” Or, “I’m in the key of G. Can’t you think like this?”

So I go to the piano and realize I can’t do [my old style] no more. So for the rest of my life, I do what all these guys gotta do: study the keys they can’t play in. Then as they study them, minors and majors, they’ll be able to play in ’em. And that’s the truth of music, and that goes for symphony guys too. They are still trying to play in the hard keys. It’s simple to write in D-flat because we play in it all the time. And F, we done wore it out, and we wore out B-flat. But nobody wore out B-natural yet. They ain’t wore out E-natural or D[-natural] or F-sharp.

GOODMAN: But why can’t a musician catch the modulation in a tune? How can that pass them by?

MINGUS: Because we all want it to be easy! I would know something was wrong, but I’m talking about the guys who can’t do it, who haven’t got the fingering to do it, yet they call themselves musicians. You gotta know how to do the fingering. You play piano? You can’t play the C scale the same way [crossing your thumb, etc.]. So you gotta know what you’re doing. It’s like starting over and admitting that even professionals gotta study and practice. Plus go to teachers. I’m sure all the guys I know do it, who are in the good positions. Buddy Collette talks about going to his composition teacher. Red Callender’s going to a teacher; these guys are my age. Who else goes?

This little kid trumpet player, Lonnie Hillyer, said, “Man, I wish I had his chops.” Wish he had his chops? He was talking about John Faddis, and I said, “He didn’t have no chops, he studied to get that proper embouchure.”

Lonnie said, “No, he was just born like that.”

“No,” I said, “he’s got a teacher right now.”

“No, he don’t need no teacher right now”—and now Lonnie wants to study. But it took a long time to prove that to him . . . First of all, his parents should be shot. They sent him to Barry Harris, who’s a piano teacher, to teach him to play the trumpet. Well, the proper start would be send him to Barry Harris for theory but Barry doesn’t know anything about an embouchure, you know, how to blow through a straw and strengthen your chops and all that. It’s Barry’s fault too; he should have told the parents, “I can teach him theory but you need a trumpet teacher, a good one—one of them old men who can sit and blow B-flats all night long.”

One thing I’d like to clear up a little more in case I haven’t is the fact that all those eras in the history of jazz, like Dixieland, Chicago, Moten swing, all those styles, man, are the same and as important as classical music styles are. The movements—like you remember Moten swing? Count Basie swing is another swing. And Jimmy Lunceford had another swing. Remember Jimmy’s band? The two-four rock [demonstrates].

Well, man, there should be a school set up where all those styles and movements are exposed to the students, and they find their medium, what is closest to them, and come out with that. I don’t mean copy that, I mean they should be able to copy it and then find themselves, as most composers do in classical music. Find which one they like and that’s where they are, through direction.

You think about it, man, even the guys in jungles, they weren’t just born as a baby and picked up a drum. Their daddy taught them how to play drums, to send messages and all that. “Somebody’s talking something.” They heard it and loved it, went and fooled with it for a while, and daddy would say, “Well, here’s how you do that, son.”

They didn’t just say, “I’m Jesus born here, hand me a drum, baby; lay a flute on me, run me a clarinet next; now I’m gonna play a little bass. Where’s Jascha Heifetz’s violin? I’ll play that for you, better than him. When we get through, hand me Isaac Stern’s.”

Yeah, that’s where the guys are today: “Give me a violin and I’ll play it for you. Jascha played it, I’ll play it too.”

And intelligent people still listen to this crap, man. I don’t want to be fooled anymore: I know when I’m out of tune, and I’ve done it intentionally and watch critics applaud. And that’s when avant-garde has gone too far. “Let’s see, here’s a B-flat seventh. I’ll change the chord from a B-flat major seventh, I’ve got an A-natural in B-flat; I’m gonna play a B-natural.” And I’ll get applause for it. Well, on the major seventh chord, that’s the wrong note. Now if the chord was not a major seventh and was a B-flat cluster, and if the chord is a row, then I can play all the notes. But [not on] a major seventh. I can play wrong notes in a chord if I want to sound wrong and have a clown band like—what’s that guy had a clown band? Shoots guns and all that?—Spike Jones. If you want to say Spike Jones is avant-garde, then we got some avant-garde guys playing, some Spike Joneses.

GOODMAN: Only he made music.

MINGUS: He could do everything, man. I don’t want to be so junglish that I can’t climb a stairway. I got to climb mountains all day long? We’re going to the moon, right? Well, I’m with the guys that wrote music that got us to the moon. Not the guys who dreamed about it. Bach built the buildings, we didn’t get there from primitive drums. In a sense we did, because primitive drums was the faith. Primitive music is the faith—like Indian music—of people who want to find out how to get there. Bach was the intellectual pencil that figured out mathematically “does this work?”

“Yes, this does, now put that aside.”

And finally, “Does this work with this?” Bach put all these things together and called them chords. Well, we go with progress and call it scales, and these things have been broken down by Schillinger and a whole lot of other guys. Now if you work in that form and then go back and say, “Man, we don’t need to know this theory,” fine, then I accept that you’re a primitive. But when you come on the bandstand with a guy who may not want to play primitive for a minute, can you play with him? That’s what the question is.

Maybe I can play primitive too but for a minute I want just one chord, a C major seventh. Now how many guys can play that—and play something on it, improvise something on it clearly? That’s what Bach could do, because that’s the foundation, and then he could put the D-flat major seventh against that. Now then you got a building, black and white, concrete and stone, and it can grow taller. Now that’s the way it is, man. Though I’m not saying that’s as modern as you want to be.

But I can’t hear for a moment when Bach was in the church. I can’t hear for a moment when he left his theory-ism. He’s the greatest theorist that ever was, man, the greatest mathematician ever lived, I know that. But he was never in church, he never realized he was in the church, man. Excuse me, he was never a minister in the church. He only wrote his self, his theory.

GOODMAN: You mean he wrote church music without being a believer?

MINGUS: Without being a member, without being a teacher. But he taught another way, man. It’s too intricate for church, unless they played him too fast. There’s this theory that they played Bach very fast.

GOODMAN: Yeah, Glenn Gould holds to that.

MINGUS: You play him slow, and it’s another story. Well, who was there to know?

GOODMAN: Now let me ask you something . . .

MINGUS: We’ll go back to Bach later.

GOODMAN: I wanted to go back to the wailing and the African thing.

MINGUS: You want to talk about John Coltrane.

GOODMAN: Well, yeah . . . because I wrote a piece once, I’ll send it to you, with the idea that all the people who were making the biggest noise about African music—talking about it more than playing it—were misunderstanding what African music was really about. African music is really . . . tribal music.7

MINGUS: Tribal music?

GOODMAN: A man plays a drum to convey a specific message, and if he’s playing for a dance he’s playing to arouse very particular emotions. The African music I know is very specific. The New Thing, as they used to call it, was totally unspecific, like an expressionist painting.

It seemed to me that people who said they were trying to get back to Africa in their music were just putting a lot of con on everybody. Or they didn’t know what they were talking about.8

MINGUS: See, I’m closer to America in a lot of ways than Africa, never been to Africa and I don’t have any African friends, but I tell you I’ve done a little reading, and I used to go with an Indian girl whose grandfather was Sicilian born. I’m sure tribal people are all the same, African or Indian, like this girl. The high-degree order monks, they write music in the cloisters. Now we have guys in the police department, they have a police band, in parades, and a dance band. The Marines have a band, sailors have one. This girl showed me a funny thing—that even though we look at people as being primitive, that the guys who played the drums for the war dance weren’t the guys who played the drums for the religious dances.

Now the people who were going to meditate and do these long five-day hikes in the mountains—what the kids now use LSD for instead of peyote—these were another set of Indian guys. What I’m trying to say is where was the governing of where the music was for all the people? When the chief was involved, elected by the tribe, that was someone who everybody respected—in primitive music—and they had dancing and celebrations. So that meant—

GOODMAN: A different music for each purpose.

MINGUS: I imagine the warriors brought their drums too, but they didn’t all play at the same time. Now, what music they did respect as being Indian music is mainly the dance music or the folk music for people who were enjoying themselves. Now, religious music—John [Coltrane] was a preacher, and I accept that.

He was trying to tell the people, “Stop shooting up dope, stop getting high. Go on a vegetarian diet, get yourself together. Get your body and mind together and see what the society’s done to the poor black man.”

He was trying to get it together. The fact that the white kids liked it, some liked it as much as they did rock, right? Like at rock concerts, they were packed in, I saw ’em. It wasn’t done exactly like the Indians did it, it was done with new religious tones. You say African, I heard more Indian in his music—Indian-Indian music.

GOODMAN: I think that’s true, and I don’t mean that John was playing African music, but a lot of the people who were talking all this pro-Africa stuff at the time used him as an example. And they’re full of shit.

MINGUS: They are, and they never heard Indian music, man.

GOODMAN: And they never heard African music either.

MINGUS: I’m sure if John had wanted it to be, he’d have gone to Africa and studied it out. But presently there’s not that much African music other than Olatunji, if you want to call that representative of African music.

It’s just drums. African music I’ve heard—there’s a tribe—I can call Farwell Taylor and ask him—but this tribe had this huge saxophone they’d sit on, and they’d all blow into it. Four, five men would play it, and it would sound o-o-voo-voo, o-o-voo-voo, like a drum played by a mouth.

GOODMAN: Like a bagpipe, sort of?

MINGUS: Man, this was like a rock, the picture I saw of it, like a rock they was blowing into and sitting on it, like a big mountain, and it was an instrument. It was from the Belgian Congo, I remember that. It was the first music I heard as a kid, seventeen years old. And this man [Farwell] loved African music, he had everything you could get.

But then one day he got some records and found out that some of them were made in Los Angeles in a studio with bamboo and shit on the floor and some local cats. And it broke his heart, ’cause he thought it was real. Here’s how he found out.

I said, “Farwell, I can’t imagine them going out to the jungle—’cause they found some very dangerous music, music from the Pygmies, who were going to shoot the warriors with darts, poison arrows. How did they get all the equipment out there? They had stereo and hi-fi. Where did they get the electrical stuff to record them?”

They didn’t have these little things [taps my recorder] in them days. And they couldn’t get those lows and highs the way they got ’em. Unless they got a powerful truck in there, and the scene was set up so Hollywood.

And wait a minute, man. What is African music? Don’t bullshit me, man. Let me go there and then I’ll know, [I’ll] come back and report the truth to you. Don’t tell me what they do. So now they send some people over, like Miriam Makeba and her brother who played trumpet, but they were black people, Africans, influenced by American jazz. What is their music? I’m still waiting for them to show me. Don’t tell me that John Coltrane gonna show me, ’cause he ain’t been there yet. Randy Weston ain’t come up with nothing yet that says “this is Africa.”

GOODMAN: There were some old African records on Folkways, remember? They used to do all those wonderful ethnic things from around the world.

MINGUS: Yeah, I don’t doubt that. [On Farwell’s records] they had a sacrificial suite, and I thought, “Wait a minute, man, they really killed somebody on this record?”

Farwell says, “Well, that’s what it says.”

Sorry, man. These nice American guys go in with cameras and sound equipment and watch ’em have a sacrifice? OK, and it sold a million copies. I mean this country’s so full of bullshit it’s ridiculous.

John was a very good man, very nice person, and the music he played told that. He was a very serious person and seriously in love with his music, a very religious man. He actually invented a new music in his so-called attempts to display African religious music. Which I haven’t heard yet, I haven’t heard him playing African.

GOODMAN: What burned me most was an article in Jazz & Pop, about five or six years ago, with some hip white asshole [Frank Kofsky] coming on about how Coltrane is the African messiah—and that’s what made me write my piece.

MINGUS: Did he mean African or did he mean American black?

GOODMAN: He was talking about African, and so was A. B. Spellman or some black guy.

MINGUS: Well, that’s why I don’t read too much because how can you say someone’s a Watts exponent unless he [the critic] lived in Watts? Let alone Africa, which is over the water. How’s a guy gonna tell me how they play music in Watts when he’s sitting in New York City? I’m not being biased, but saying he represents a new music for the black people? That’d be nice because they sure need one to bring ’em together again, man.

• • •

MINGUS: Does history show that there has always been a battle between the avant-garde, the up-and-coming artists, and the established artists? In painting, in anything? When the king said, “I award this man, I want this man to paint my portrait”? Maybe Van Gogh was one of the great portrait painters, and was there a critic around to say, “He did a lousy job on the king”?

GOODMAN: Talking about the last two or three hundred years, yeah, critics were around. They’re easy now, compared to then.

MINGUS: Yeah, because then they tore you up. Tore up everything about you, as a human being, where you came from, who’s your father, your mother . . . Has there always been the avant-garde?

GOODMAN: In a sense, yeah.

MINGUS: I got the word from Barry Ulanov, who laid the word on me. He once called me avant-garde, and it’s not so, man.

I’m not avant-garde, no. I don’t throw rocks and stones, I don’t throw my paint. How could he say something like that?

GOODMAN: Well, a lot of people think avant-garde means anything or anybody that is making a new sound, or a “new thing.” And that’s wrong; it means more than that.

MINGUS: Well, where did the word come from?

GOODMAN: It’s a French word, and it means literally the advance guard, like in the army, troops advancing, the front rank—

MINGUS: The best—

GOODMAN: Yes, and everybody else follows along back here.

MINGUS: So this man was saying that Coleman Hawkins and Charlie Parker were all behind Teo Macero and John LaPorta and myself?

GOODMAN: That’s why it’s wrong.

MINGUS: He’s an idiot. I’m just discovering this, man. I didn’t really know it was a French word, it never really got into me. All I know is that he said these people were the avant-garde, and he named ’em—John LaPorta, Lennie Tristano, Charlie Mingus. This was Barry Ulanov. He’s an idiot, man.

GOODMAN: Well, no, because he was using the word in a 1950s, labeling way. But in terms of the arts, it also means somebody doing really new things. See, this is what we were saying about Varèse the other night—

MINGUS: Varèse! That’s the composer, that’s the one I was telling you I was listening to, when I was listening to Red Norvo.9

GOODMAN: Varèse started all kinds of wild things, began to do electronic music before there was even tape!

MINGUS: Right, and he was avant-garde.

GOODMAN: He was called the most avant-garde composer around. And he knew better. He once told somebody who called him the leader of the avant-garde, “No, there’s no avant-garde. There are only people who are a little bit late.” And that’s beautiful, because it really shouldn’t be a question of people being either advanced or late.

The reason the critics use this is because it’s a handle, a label, an easy kind of way to put people in categories. No musician, no artist likes that because they all say, “Oh, I just play music, I just do my thing, I paint.” Well, OK, that’s fine, but—

MINGUS: But when their system has shown up what they’re doing—

GOODMAN: Yeah, you want to say, “All right, what do you relate to, man? What the hell is your thing? You do your music, your painting, your dance, but how do you relate to whatever has happened before?”

So a term like avant-garde comes into being, meaning in shorthand someone who is doing things that haven’t been done before. So when Barry Ulanov said that about your music, he probably was saying it in a complimentary way, you know?

MINGUS: Yeah, but when you think about how painters go about doing their paintings—or some of the painters—I’m told they put blindfolds on, go over to the canvas with any color they want and smear it on. Or they stand back, take a big bucket of paint and splash it on the canvas, then they go to the canvas and clear it up.

GOODMAN: Or the thing about the baboon, a couple of years ago, remember that? They had a baboon throwing the paint. He had a good time. Everybody loved the painting, man [laughter].

MINGUS: Yeah, I remember the baboon. Now, I love children, man. I have some of my own, less than teenagers. But finger painting, it’s beautiful for kids.

GOODMAN: Yeah, my kids are doing that.

MINGUS: But it’s not beautiful for adults. They should grow up.

Let’s say it like this, man. The guys who throw paint on the canvas with rocks and glue have won. They destroyed us, the guys who can play, the guys who can paint, man. They have won the game. I go to museums now, I see shit.

GOODMAN: Literally, on the canvas.

MINGUS: On the canvas, man, and they’re winning now. I went to the Louvre, man, and I saw shit. They are catering to—you know whose fault it is, man, in this country? I don’t know whose fault it is in Paris or in Copenhagen, but the fault [here] lays on Nat Hentoff, Barry Ulanov, they’re like all the guys who left the ship when Jesus stayed on. They’re like all the guys who stayed under the canoe when Jesus Christ got out and walked the water. They left the boat when it was sinking, man. No, they didn’t leave, they stayed on and it sunk. He had to come back and save ’em. It’s sad, man, it’s very sad.

GOODMAN: OK, I got a question for you about what the aesthetic people call form. I hear a piece of Ornette’s music and, for the sake of argument, I hear the form there, I know what he’s doing.

MINGUS: Wait a minute, are you saying that Ornette Coleman is avant-garde? Do the critics call him avant-garde?

GOODMAN: Let’s take somebody else.

MINGUS: Do the critics call him avant-garde? Down Beat hasn’t said anything in the last ten years.

GOODMAN: I wouldn’t put that label on him because it means two things—a person’s doing things that have never been heard or done before, and it also means that he’s a creative genius, or at least that’s the figurative meaning.

And both of those meanings are bullshit, so all you can really do is throw out the term. Like you wrote in that Changes piece [“Open Letter to the Avant-Garde”], where you said Duke Ellington told you about doing avant-garde music—“Let’s not go back that far”—[meaning] we shouldn’t even deal with that. He was right because it’s a term that you want to avoid.

MINGUS: I like Duke’s word better than the other guy’s [Varèse]. No, they’re both just as good.

But you know why it concerns me so much? Because it’s keeping jazz musicians out of work. This classification, it’s keeping jazz musicians out of work. All the fights that are going on in jazz, the rock-and-roll guys are still working—that’s the enemy—and they can’t even blow their nose yet.

GOODMAN: And they’ve got their avant-garde too. Shit, rock-and-roll’s been going for twenty years, as bad as it is, you know. So they got an avant-garde too, John McLaughlin and people like that.

MINGUS: That’s good to know. John McLaughlin’s out of work?

GOODMAN: Far from it.

MINGUS: But [our] avant-garde is out of work, man. That’s me, I’m out of work.

GOODMAN: You always said that they cut you out of work because they’re fooling people, they’re taking your market. Albert Ayler, God rest his soul, and Pharaoh Sanders and those people are involving folks in phony music who should be listening to you, to put it bluntly. I’ve heard Ayler’s records, heard him play once at Slug’s, and he turned me off so bad I had to leave.

MINGUS: God rest his soul. I never heard him. I read an article about him.

CHAPTER 1 COMMENTARY

John Goodman on Mingus and the Avant-Garde: Reflections over Time

When we had our talk about the avant-garde, I was really rapping about a term I had obviously grown to detest. Mingus had been burned by it but wanted to know more, so it was a good discussion. On many occasions he had a lot to say about avant-garde jazz, so-called, but his major points are in two pieces: the original album notes to Let My Children Hear Music, and a 1973 blast, “An Open Letter to the Avant-Garde,” that codified some of the opinions he expressed in this 1974 interview.10

By then the avant-garde concept had been debated up and down, in part because of confusions over where and how it applied. Some of this confusion was reflected in my comments. We talked about it in cultural, artistic (formal), critical (categories), and economic terms. A major point I didn’t get to is that the avant-garde is nearly always in some sense oppositional—either in a political way (there is lots of that in Mingus’s music) or in response to attempts to co-opt it by mass culture, as art critic Clement Greenberg discussed back in 1939.

When he and Harold Rosenberg did famous battle in the art world of the 1960s, jazz too was more than ever subjected to ratings, polls, sales figures, and bookings, and a few critics began to talk very negatively about these things. “Avant-garde” in their eyes was just a marketing label, though Barry Ulanov might not have agreed.

The term also means “cutting-edge” or innovative and in that sense has become so inclusive and commonplace as to be worthless. Rosenberg saw that the interaction of art and business and politics was crippling artists. As the champion of action painting and the abstract expressionists, he talked of painting as “an event” and seemingly stood with Mingus’s enemies, the guys who throw paint at the canvas.

Rosenberg also loved to throw brickbats at the art establishment: “What better way to prove that you understand a subject than to make money out of it?” Being so dependent on commerce, jazz has always fought for its independence—not only from the record business but from many of the pressures of mass culture. Bebop’s insistence on being regarded as art music—not entertainment or pop—is only one example, and Mingus was always and forever on the side of art. Our subsequent interviews go into the economics of the jazz business and how they frequently collided with the demands of his art.

So the avant-garde concept seems to contain two contradictory sub-meanings. One makes it an expanding, liberalizing, form-breaking, democratic, sui generis force à la Rosenberg; the other, as in the Greenberg view, makes avant-garde art a breakaway outgrowth of an outmoded but still valuable high-culture tradition.

Salim Washington, jazz musician, teacher, and critic, wrote an interesting piece proposing that Mingus represented the true avant-garde spirit in jazz (as opposed to some of the noisy revolutionaries of the ’60s), that Mingus synthesized tradition and “self-expression” functionally and more musically than anyone else in jazz has done.11 By that assessment, Mingus’s music would subsume, to use my terms, the Greenberg-Rosenberg controversy.

Washington looks at Ornette Coleman’s music and its influences on Mingus (a subject I haven’t seen treated anywhere else—and the influence is there: listen to 1960’s Mingus Presents Mingus, for instance). This musico-sociological approach to jazz history prompts one to look at Mingus through a new lens, though Washington tries to show (not always convincingly, I think) that the avant-garde aspect of jazz has deep historical and performing roots, going back even beyond Ellington and Bechet.

He wants jazz to contain the avant-garde, not segregate it as some weird 1960s offshoot: “The historical [European] avant-garde, in its seeking to shake up the foundations of the art world, strove to separate itself from the traditions upon which they were commenting. By contrast, jazz artists—of all stripes—have not tried to flaunt their prestige and artistic standing or mock the sacral aura of the art world, but rather have been preoccupied with attaining such prestige that European art music routinely enjoys.”

From all the comments Mingus made on many occasions—not just in these interviews—I think he would agree with that. As he concluded here, it boils down to making a living. And further, he would maintain that there is no real avant-garde unless it’s great musicians like Clark Terry who have learned their craft and mastered their art.

Alex Stewart, in his book Making the Scene, offers an interesting comment on Mingus and the avant-garde:12 “Many of the techniques championed by Mingus—additive composition or layering, collective improvisation, lack of concern with playability, rich unisons—form the core of the experimental or avant-garde composer. Although Mingus often disparaged the avant-garde movement, many avant-garde musicians continue to cite Mingus as a prime influence.” Yet Mingus’s innovations always built on either following or fracturing tradition, and “avant-garde” seems a real misnomer for that kind of development. His music is, above all, eclectic. The only sense in which the term avant-garde really applies to Mingus may be in his political-cultural stance.

Perhaps his greatest breakthrough was to reconcile collective improvisation in a modern context with the formal demands of the music. Nobody has been able to do that with such gutsy power and joy since Jelly Roll Morton, another so-called avant-gardist, the first to make jazz into a compositional art. If Morton led the way to modernism in jazz, Mingus was its first true postmodernist.

Sy Johnson on Collaborating with Mingus

As one of the insiders participating in the creation of Let My Children Hear Music (he orchestrated and arranged much of it), Sy had exceptional stories to tell about how the album came together. Our talks also contributed a great deal to my understanding of Mingus and his music. As frequent arranger and sometime orchestrator for Mingus, Sy became (I will say it even if he won’t) the man’s musical right hand.

These comments also help explain how Mingus used traditional—even classical—procedures and methods to produce music that was anything but traditional. That is to say, how he both used the rules and broke them. Maybe all “avant-gardists” do this, but Mingus was very precise about which rules and how they were to be broken.

Sy refers in this 1972 conversation to a piece that was done in concert and did get recorded but was only issued later, “Taurus in the Arena of Life.” How Mingus infused Art Tatum into that work gives insight into how he used musical materials of all kinds and how the band participated in that process. Yes, his approach sounds like the way Ellington did things—but Duke never stitched the quilt together quite the way Mingus did here. Sy’s description of the process in “Don’t Be Afraid, the Clown’s Afraid Too,” reminds me of how Mingus typically worked in the small-band context, the Jazz Workshop, and how he invariably got musicians to play things his way, though with their own voices.

• • •

GOODMAN: Two things I thought of that I wanted to ask you. One was precisely what kinds of innovations you hear in Mingus’s music. The other is your idea of where his music comes from, what kinds of sources you hear him using, besides the obvious with Ellington and so forth.

JOHNSON: Right. Well, I think the fact that Mingus came on the scene when he was about eighteen or something like that, about 1938 or 1939, when he first began to come out in Los Angeles, he came out as a fully developed artist at that point. He was a bass virtuoso and he had his thing very fully developed at that point. He had influences. Everybody knows about the Duke Ellington influence. It is not as well known that Art Tatum was a very important influence on him. Mingus keeps referring to Tatum voicings. He played with Art Tatum briefly and there was also a teacher he had, Lloyd somebody—

GOODMAN: Lloyd Reese?

JOHNSON: Lloyd Reese, right, who was an important influence. But basically with Mingus, the music came out of experience. I mean, he is constantly transforming material that he picks up from [all kinds of sources]. There is, for example, a section that is very difficult for the trumpet to play in “Ecclesiastes” that Mingus told us one night was a French horn cadenza from a classical piece, inverted. He just turned it upside down, and the minute he explains that you say, “Ah yes, absolutely. That’s where it came from.”

He gets expansive every now and then and says, “Hear that? Well listen to that real carefully and you’ll hear that it is really—” and it’s some old obscure pop tune or something like that. He just transforms material, a lot of material that’s around him. Composers have always been doing that; it is a perfectly legitimate thing. But he just takes in enormous amounts of music from every source that he can. And it all gurgles around in there and is finally spewed out as something that is quite uniquely humorous.

We are doing a piece that we did in the concert but [that] has not been recorded yet [“Taurus in the Arena of Life”]. Partly because I helped him make the orchestration for it, because he thought he might like to do it in the album but he hadn’t finished writing the piece yet. There is a whole middle section that he has completed since then that we are going to have to deal with, I guess the next time we record, and I’ll [orchestrate] the whole thing.13

But there is one section of that, at the end, and he just said, “There is an Art Tatum voicing and I’ve always wanted to use it someplace.” And he played this Tatum voicing on the piano for me. He said, “I have always wanted to use that someplace. I think I’m going to use it right here.” So he immediately took that fabric, and it was like a quilt and he stitched it into the piece and it immediately became part of the piece. It was not capricious at all.

GOODMAN: That also makes me remember your story about adding the 8/8 piece toward the end. Then he comes along and changes the whole thing.

JOHNSON: On “Clowns”—“Don’t Be Afraid, the Clown’s Afraid Too”—our original routine on it, the tune didn’t seem to come to any conclusion. It was lacking a final section to it, at least I felt it was. So I called Mingus the next day and explained my feelings about it. I told him I thought he should write something to open it up. Maybe just something with one chord but something that would get away from the very strict structure that the whole piece had going for it.

He agreed, thought that would be good, and he says, “You write something. Just write something that you hear and if it doesn’t work, you’ll know.” So I wrote an 8/8 section, a very funky 8/8 section. In a sense I was thinking, well, this will probably be the first time that Mingus has ever played anything in 8/8 on record. I thought it would be interesting to see whether he responds to that as an extension of himself or how he gets to it. It was like a vamp with solos running through it.

So we got to the date and started to rehearse that part (we were rehearsing in sections because it was such a long piece) and we finally got to that section, and the band seized on it as something familiar that they could get their teeth into. They began to get a good feeling right away. Dannie Richmond particularly began to really cook on it. We ran it a couple of times, and then suddenly Mingus stopped the band and said, “That’s rock and roll.” He says, “You’re not going to find any rock and roll in my album.”

And he just started walking around telling people what to play. He walked up to the tuba player, Bob Stewart, and said, “I want you to play in 3/4, I want you to play just um-pah, um-pah. Eddie Bert, I want you to play something like this . . .” He assigns specific roles to two or three different people and then he says, “Anybody else who feels like adding to that, we are going to play some clown music. Now I want you to make it sound like a clown.” And so we went back and it worked immediately. It was obviously what the piece needed at that point. Then later on, in the overdubbing of that, he deliberately included references to the old bebop themes that are in there.

GOODMAN: Oh, that came after.

JOHNSON: Right, that came after, and he just wanted a subliminal reference to another kind of music. It is his own private little inside thing. It is not terribly audible. Teo was dying to play his alto. He loves to play and does not get many chances anymore. And Mingus likes his alto playing and talked him into bringing his alto around to one of the overdubbings. So he got Teo to play and Teo sounded, you know, he can play space music like a freak. And so Mingus kept saying, “Yeah, we are going to have the masked marvel on this album,” and actually Teo didn’t get credited in the notes with it, but he was delighted that he got Teo actively participating as a player. And Teo was having a ball. He was really elated.

GOODMAN: So after they were playing your 8/8 section, and then he stops it—you said the band was getting into it, it was going well. That reminded me of another story you told when you all got cooking and he was off the stage, not participating, and then had to jump back in there and destroy the tune. Of course, this time he did not.

JOHNSON: No. He just made a decision, which I couldn’t get him to make before.

GOODMAN: And I don’t know what to conclude from this except I guess he has to always have his hand in it.

JOHNSON: Oh, I think that’s true, but in some ways he impresses me as not being egotistical about his music. Or about having to take charge constantly. And that he’s willing to let it go.

One of the things he understands is that other people may be performing some service that he doesn’t care to. Because he can orchestrate but he does it in a very deliberate, slow way. I mean, he just—it’s laborious. He actually leans on the pencil. It’s quite a process. And so under those circumstances it would take him forever to orchestrate something, orchestrate a body of pieces, and so he has used other people to orchestrate his music.

Bob Hammer was very successful at that. He’s a piano player who was around here, in 1962 or something like that, when he did Mingus’s masterpiece, as far as I’m concerned, a brilliant piece of orchestration and brilliant performances of The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady. That texture, as far as I’m concerned, is the definitive Mingus texture. It was the texture also, in doing the writing for this album and the [Mingus and Friends] concert, that I decided to deliberately not emulate.

I told Mingus, it isn’t adding anything to simply find whatever secrets I need to know in order to make the band sound that way and then go ahead and write. There were some other qualities I could bring to the music, that I was hoping he would find acceptable, and he has. I know in particular—with “Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife,” he’s very moved by his own recording of that now. He always holds it up to me as an example of success, as far as my efforts were concerned.

So he constantly says now, “You really worked too hard on this, Sy.” He says, “On ‘Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife,’ you were really working on that one.”

But it’s been . . . a fascinating experience. And he’s quite content to give responsibility to other people when he prefers not to do it. He doesn’t like to conduct, for example.

Oh, another interesting note about his compositional thing is that, in going over to talk with him about music that frequently only existed on a tape of some kind, or on an old record with no written notation or score—in talking about that, I found that he hears the music in a very emotional way.

I mean, he knows when it goes up and when it comes down. He has got the emotional peaks and valleys of the piece down, and frequently the specific pitches aren’t terribly important. He could just as easily have written down other notes that would have satisfied his needs at the same time.

So when he talks about it, he’ll say, “Oh that probably goes here,” and he will take it to another place in the piece and move on right from there.

GOODMAN: Kind of like tape editing?

JOHNSON: No, it’s just that what he hears is not as much specifics as far as pitch is concerned, as [it is] intensely emotional energies, flows of matter and volume and all that business. The pitches in a lot of his pieces are very specific. I mean, you can’t fuck with “Clowns.” When he gets into that kind of thing, it takes an enormous amount of discipline to sit down and just keep channeling those lines, one on top of the other. I mean, layering the thing.

But in a lot of cases the music is just much more expansive than that, so there is a big contrast between the tightly disciplined Mingus of “Clowns,” which I think is one of his masterpieces, and some of the more expansive, impressive pieces.

GOODMAN: Like The Black Saint?

JOHNSON: Right, that kind of piece. He could have easily gone someplace else with that music. It isn’t like a John Lewis composition, for example, which is inevitable. One thing inevitably follows everything else. John will never forget exactly the sequence of things happening. With Mingus, the options are open, they’re open to change even after the piece is played, recorded. He’s responding to another drummer or another source in his head. And some of the most volcanic music he has written has been written in that way.

GOODMAN: Then you’re suggesting this is a kind of polarity in his music. I mean, the “Clowns” Mingus and then the Black Saint Mingus?

JOHNSON: Right. Or even with that piece for Roy Eldridge—the “Little Royal Suite”—which is that [second] kind of Mingus. It’s the volcanic, volatile music that is very difficult to get people to play because they frequently have to make noises and he has written nonmusical instructions to them on the music, and they are expected to supply a wide palette of sounds. Again, it’s helpful to enumerate: he’s got the very disciplined Mingus that can write a piece like “Clowns” or like even “Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife,” which is somber and very, uhh, controlled—although that could have gone other places too. “Shoes” is one of the pieces, once you see the structure of it, that he could have taken some other place. But “Clowns” is quite unique. He was very surprised to find out that that was not a sixteen-bar phrase.

And that’s another thing. His music frequently comes out into odd numbers of bars. He sometimes has a tendency, if one thing comes out at fourteen bars, to make the next section eighteen bars long. So that in totality, it turns out to be a thirty-two-bar phrase. He thinks that it should be more regular than it is. He’s a little suspicious of his own instincts in that regard. But if he breaks a three-bar phrase, then he will follow that with a five-bar phrase.

In “Taurus,” he had written a brilliant series and built the whole piece on three-bar phrases. The recording of it was left off the album for space reasons and because Mingus actually finished the piece after the recording was done. But it was brilliantly written in three-bar phrases.

On the recording date, Mingus yelled something about “we need to settle down someplace.” He inserted one four-bar phrase, just extending one of the three-bar phrases for an extra measure, which killed me. I hated that. It drove me right up the wall because it was such a perfect structure before. Mingus very obstinately decided that he needed to settle down somewhere in the middle and added one measure to it, which destroyed that beautifully conceived framework that seemed to have been entirely subconscious on his part. It wasn’t planned: he was following his ear, and whatever his muse was telling him. Only after the fact of dealing with it, when trying to record it at an earlier time, did he want to “settle down” and make it more regular at one place. He just had to change it.

So it still galls me slightly that he would fuck with that perfect structure that he made. ’Cause it was perfect. He just had to lengthen one of them out to conventional length to satisfy some other requirement that had nothing to do with the act of writing the music. It was separate from the creative impulse of putting the music down.

But, his music is just full of earth and it’s always got its feet in the dirt. I mean it’s jazz, it has human cries in it, and it’s full of humanity. Mingus’s humor is [unintelligible].

GOODMAN: I suppose in his sense of form he’s got to have something to grab onto.

JOHNSON: Right, I know that. He mistrusts though, sometimes, his own . . . So he will, after the fact, regularize something. He’ll come across a chord sequence that seems to exist, it doesn’t even have a melody sometimes, just a series of chords that seem designed to do nothing but finish a phrase. He doesn’t have anything particular he wants to write there but he feels he should have a certain number of more bars. It will be just some chords that will finish it. Then he will have written sixteen bars and that will be the end of it. It’s just an interesting thing.

NOTES

1. There is a good discussion of the subject in Eric Porter’s What Is This Thing Called Jazz? African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), with a full chapter on Mingus. See especially 22–23, 37, 192.

2. Mingus intended to move to Majorca to “work on his autobiography and composition,” according to a Jet magazine notice: “Bassist Mingus Heads for Venice, May Quit U.S.,” August 30, 1962.

3. The full Time article is here: www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,827882,00.html.

4. Kenneth Rexroth, “Some Thoughts on Jazz as Music, as Revolt, as Mystique,” reprinted in Bird in the Bush (New York: New Directions, 1959); or see www.bopsecrets.org/rexroth/jazz.htm. As of 2010, the Mingus Orchestra continued the explorations into jazz-poetry performances that Mingus, Rexroth, and others began in the 1950s. See www.mingusmingusmingus.com/MingusBands/ChamberMingusPR.pdf.

5. Ornette could read; that wasn’t the problem. There’s no “simple” answer as to why he couldn’t or wouldn’t play straight, despite what he said in talking with critic Whitney Balliett: “The other night, at a rehearsal for the concert I played in of Gunther Schuller’s music, Schuller made me play a little four-measure thing he’d written six or seven times before I got it right. I could read it, see the notes on the paper. But I heard those notes in my head, heard their pitch, and what I heard was different from what Schuller heard. Then I got it right. I got it his way. It was as simple as that.” Balliett, Collected Works: A Journal of Jazz 1954–2000 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2002), 116.

6. Nesuhi Ertegun partnered with his brother Ahmet to produce some of Atlantic Records’ best-known jazz and pop musicians, including Mingus, Coltrane, Coleman, the Modern Jazz Quartet, and many others. He was also Mingus’s friend.

7. It would probably be more politically correct today to use the term “ethnic,” but this was 1974 and I meant “tribal” in the sense of totemic, a specific and integral part of the culture.

8. A good discussion of Coltrane’s “Africanism” and related issues is found in Ben Ratliff, Coltrane: The Story of a Sound (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007). See especially 154–78.

9. Recently, the story (rumored for years) came out about Varèse’s fascination and work in 1957 with New York jazz musicians, including Parker, Mingus, Teo Macero and others. The “improvisations” are diagrammed and recorded for playback by the International Contemporary Ensemble in “Varèse, Charlie Parker, and the New York Improv Sessions,” Edgar(d) (blog), July 19, 2010, http://iceorg.org/varese/?p=200.

10. Sue Mingus has published the full Children liner notes online as “What Is a Jazz Composer?” See www.mingusmingusmingus.com/Mingus/what_is_a_jazz_composer.html. It is a brilliant, rambling, ranting piece in which Mingus declares his allegiance to tradition in jazz and classical music. “An Open Letter to the Avant-Garde” broaches the Clark Terry idea he followed up on here, of getting really accomplished jazz musicians to show up the pseudo-avant-garde players. Read it at www.parafono.gr/htmls/mingus_openletter.htm.

11. The piece is entitled “All the Things You Could Be by Now: Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus and the Limits of Avant-Garde Jazz.” No longer available online, it has been collected in Uptown Conversations: The New Jazz Studies, ed. Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 27–49.

12. Alex Stewart, Making the Scene: Contemporary New York City Big Band Jazz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 224.

13. Sy added this note in a follow-up interview in 2011: “I was doing my usual thing of minimizing my role so as not to spoil his image. Actually, he only gave me an eight-bar fragment that he said had some Tatum voicings he knew from rehearsing with him, and he wanted it used ‘the way Duke uses Harry Carney in the band.’ The Spanish vamp, and the ending which I really liked, he wanted to [use to] flesh out the piece. I wrote the open harmonics and the counter-motifs to fill in the spaces and reflect Carney, I guess.”