Читать книгу Fela - John Collins - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

THE BIRTH OF AFROBEAT

Fela in London

In 1958 Fela’s mother encouraged him to go to England to study medicine or law. He went to study at Trinity College in London, but against her and the rest of his family’s wishes he switched to music. At Trinity, he got his training in formal music and trumpet and also fell in love with jazz and with the highlife of the London-based Nigerian musician Ambrose Campbell and his West African Swing Stars (or Rhythm Brothers). In 1961, Fela formed a jazz quintet and then in 1962 the Highlife Rakers. Later he formed the Koola Lobitos, with his close friend “Alhaji” J. K. Braimah on guitar and Bayo Martins on drums. According to Martins, Fela was “a cool and clean non-smoking, non-alcohol-drinking teetotaler.” In a 1982 interview with Carlos Moore, Braimah makes a similar observation, stating that although Fela was a ruffian he “looked like a nice, clean boy … a perfect square.”1

Fela and his cousin, Wole Soyinka, shared a flat in the White City area of West London. It was in London that Fela met his wife Remi, who had Nigerian, British, and Native American ancestry. Even though she says Fela was a rascal and teddy boy (a sort of early English juvenile-delinquent rocker), she fell in love with him. They got married in 1961 and had three children. Yeni and her brother Femi were born in London in 1960 and 1962, respectively. Their younger sister, Sola, was born in 1963 in Lagos.

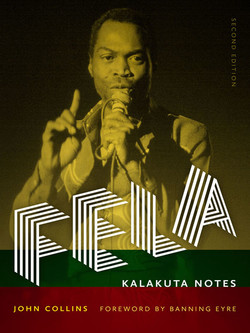

Twenty-one-year-old Fela as a student at Trinity College in London in 1958.

Returning Home

When he went home to Lagos in 1963 he continued to experiment with jazz. I will let the music journalist Benson Idonije explain this story.2

When Fela came from London in 1963 he came to Nigeria as a jazz musician, even though he had played highlife in London. He abandoned highlife and played strict jazz after he met in London the West Indian saxophonist Joe Harriott who used to play Charlie Parker–style bebop, and the West Indian trumpeter Shake Keane who played like Miles Davis. Though Fela was good enough to play with them, he disgraced himself as he couldn’t cope with the improvisation. But that encouraged him to practice to play jazz and he went on to redeem himself. Before he left London he joined some West Indians to make a strict jazz album, which he brought to Nigeria.

So when he came back to Nigeria he didn’t like highlife at all, and he met me as I was presenting a jazz program on radio called NBC Jazz Club. He came to meet me in the studio and introduced himself and so I interviewed him on the program and we became friends. Then he started coming to my house and in 1963 we formed the Fela Ransome-Kuti Quintet [with Benson as its manager]. This Quintet had a base at the Victor Olaiya’s Cool Cats Inn where we were playing every Monday night. In the group Fela was playing trumpet and piano. On bass was Emmanuel Ngomalio, on drums was a guy called John Bull, on guitar Don Amechi, a fantastic guitarist, and we also had this organist Sid Moss. In later years we had the saxist Igo Chiko and other musicians were coming as guests; like Zeal Onyia on trumpet and Art Alade and Wole Bucknor on piano, Bayo Martins on drums—then later Steve Rhodes [piano].

The Koola Lobitos

With J. K. Braimah and some others in his jazz quintet, Fela re-formed the Koola Lobitos dance band, and he called his music “highlife-jazz.” Fela played trumpet and keyboards, and the group was based at the Kakadu Club. They played alongside King of Twist Chubby Checker and the young Jamaican ska artist Millie Small, who both toured Nigeria in the mid-1960s.

At the same time, Fela was working as a music producer at the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC), a job he considered dull and deadening—and was sacked after a few years. Dr. Meki Nswewi (a musicologist at University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and now South Africa) was Fela’s colleague then. As he recalled:

Nothing was very radical about Fela in those days [1965]. He was running his Koola Lobitos group at the Kakadu Club at a hotel he had taken over on Macaulay Street. Fela had a very good Yoruba sax player called Igo Chiko whom I later recruited for some university drama productions. In Studio A of NBC there was a grand piano and Fela would go in there and experiment with his compositions during office time. He was concerned with trying to find a sound, as he wasn’t happy with his jazz-highlife.

The NBC also had a good record library, which the British had set up [and which Fela used]. Fela was also having problems with the NBC. The organist, Mr. Ola-Deyi, was in charge of the Music Department, and, as he was a fairly old man, he didn’t like Fela whom he thought didn’t take things seriously—coming late for work, etc…. Also, in those days no one was getting paid music royalties, and Fela was agitating for royalties to be paid for his music. So his records were not played. Another reason for this banning was that he was beginning to use a language they called “not to be broadcast.”3

It was after leaving his job at the NBC in 1965 that Fela again reorganized the Koola Lobitos and this time brought in the drummer Tony Allen. One of the first Koola Lobitos hits of the time (1967) was the jazzy highlife “Yeshe Yeshe.” But although Fela was to become popular in Nigeria in the 1970s he was then relatively unknown. And it was in Ghana—the birthplace of dance band highlife—that his music first really caught on. Koola Lobitos made many trips to Ghana from 1967, the first being with Nigerian trumpeter Zeal Onyia.

Ghanaphilia

Fela came to like Ghana so much that when he was in Lagos he had to have a constant supply of Ghanaian tea bread and Okususeku’s gin sent to him. He also fell in love with Ghanaian women and the country’s legacy of Nkrumaism. It was Fela’s friend Faisal Helwani and his F Promotions Company that organized these early tours. As Helwani recalls:

The Nigerian promoter Chris Okoli came to Ghana in 1964–65 with Fela’s manager or agent, Steve Rhodes. I went to Nigeria with them, as I wanted to bring some Nigerian musicians to Ghana. Ghana was like Hollywood for Nigeria at that time. So Chris Okoli introduced me to Fela at the Kakadu Club and we became friends straightaway and he became like a brother to me.

I visited him a few times in Lagos before promoting him here in Ghana. At the beginning Fela had a lot of sense of humor. As for the womanizing—it was there, but he was married and was living with his wife. He was jovial and liked to have a good time. At that time Fela was not into politics.

Then I started promoting him here in 1967 and the Ghanaian tours made him popular in his own country. He liked to work for me, as I never cheated him. If I’m on tour I pay him in advance, rain or shine. On one of these tours that I brought him to Ghana for, out of fourteen days it rained heavily for thirteen. There was only one day left for the tour to end and my hope was on that day, which was in Kumasi. I went down to Kumasi with Fela and another band called the Shambros (the resident highlife band of the Lido nightclub in Accra) in two busloads. The weather seemed OK and we said thank God. But as we reached the outskirts of Kumasi it started to piss down.

We set up our equipment to play but the rain wouldn’t stop. By 9:30 p.m. only two people had bought tickets. Now, how to pay accommodation? No money. So I decided to drive back to Accra as we had a hotel booked there. I paid the two people their ticket money and dashed them taxi money to go home. Now, driving back to Accra from Kumasi and when we were almost at the doorstep of Nkawkaw more than halfway back, we saw this huge tree that had fallen across the road, completely blocking it. Now we had to drive back to Kumasi and take the Obuasi road to Accra through Cape Coast. While I’m going through all this agony Fela was sitting next to me in the Benz bus with half a bottle of Okukuseku gin. He said: “Ha-ha-ha promoter, rain beat you, me I’ve got my money.” The next day I still had a balance to collect for Fela, so I sold one of my taxis to pay him. Fela always respects me for that.4

El Sombreros, the Koola Lobitos, and the Latin Touch

El Sombreros, a youthful pop band that played mainly rock music and soul, were put together and promoted by Faisal Helwani to support a Ghanaian tour of Fela’s Koola Lobitos in late summer of 1968. This is what one of its members, Johnny Opoku-Akyeampong (Jon Goldy),5 told me about the group:

The line-up of El Sombreros was Bray on drums, Kojo Simpson on bass, Turkson on rhythm guitar, Alfred Bannerman on lead guitar,6 me on vocals, and a female singer called Annshirley Amihere who was a shit-hot soul singer. Our signature tune was “Take Five” an old jazz tune. We also played other jazz-influenced tunes like Jimmy Smith’s version of “Got My Mojo Working.” Faisal and his F Promotions organized the tour, which consisted of three gigs only. The first one was at the Lido nightclub, then Kumasi City Hotel and The Star Hotel, respectively. There was an MC in tow who traveled with us known as Big J and even a journalist known as Jackie. The Koola Lobitos stayed at the Grand Hotel during the tour.

This is what Johnny told me of Fela’s character at the time:

I think Fela had a sense of his own destiny even back then, and no one could mess with him. I found him and his musicians to be quite high-spirited, at times irreverent and a lot of slapstick humor. But on stage they were a tightly disciplined band. Fela was already sporting his tight-fitting James Brown–like costumes back then. The music was basically the Nigerian style highlife with a jazzy feel to it. Even back then you could tell he was a superb arranger. His approach then was a typical Western-style format similar to the Sammy Obot–Uhuru [big band] style, but less swing big-band style and certainly not like the guitar-band style typical of other Nigerian artists. Also at that juncture the African shamanic feel was not yet in evidence in the mix. Fela was a shit-hot trumpeter who always strained to push the limits of the music within the conventional highlife structure. As for the political stance I saw nothing like that during ’68 during the tour.7

This is what Alfred “Kari” Bannerman told me:

I remember Fela would sometimes start the band off on a tune, go to the bar and down a full glass of transparent liquid, and then to my surprise go back on stage to play blistering solos on his trumpet! Many years on Dele Sosimi pointed out to me what I thought was gin was actually a glass of water, as Fela didn’t drink8—but smoked all right. At the time having left the GBC [Ghana Broadcasting Corporation Band] where long chord progressions were the order of the day, I was taken in by the two-chord modal nature of Fela’s compositions. But things were tough as this was before the onslaught of Afrobeat and they [i.e., the shows] were sparsely attended. The guitar the Koola Lobitos used had a nail sticking out, holding neck to body!9

The reason Helwani chose the name El Sombreros for the pop group was that at the time Latin- and Spanish-sounding names were a vogue with some pop bands in Ghana and in fact the country’s leading soul band was called El Pollos. Likewise the Sierra Leonian leader of the soulish Heartbeats band, Gerald Pine, called himself Geraldo Pino. Furthermore, Fela’s band was called the Koola Lobitos. So Faisal Helwani insisted that the name of the Fela’s youthful support band (originally called the Beavers) should likewise have a Spanish-sounding name and that the El Sombreros should wear Latin-style costumes. Here are Bannerman’s views on this:

I really didn’t like the shiny, frilly multicolored costume, plus [sombrerotype] hat. We were playing “Jumping Jack Flash,” the Rolling Stones, etc. But it wasn’t something that jelled with my soul, and who would like to be part of a band named like they were Mexicans? On the other hand, Fela I found intriguing and very smart as he had his signature designed shirts, which were almost collarless.

Despite the fact that the Koola Lobitos did not sport Latin costumes they were in fact influenced by Latin music to some degree—as in the late 1960s Fela was not only drawing on jazz, soul, and R & B, but also on Latin salsa music: as in the songs “Oritshe/Orise” and “We Dele.”10 “We Dele” is in a minor-key bluesy-jazz style, and “Orise” is more highlifish, but both use Latin-style horns to accompany and/or respond to the vocals.

This Latin touch in Fela’s music may have come from several sources. Fela was an avid listener of modern jazz, and the Cuban mambo had made a big impact on jazz from the late forties, such as with the “Cubop” associated with Dizzy Gillespie, the Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo, and Stan Kenton’s Afro-Cubists band. Then came the “pachanga” dance craze of the 1960s that swept across the globe, including Africa,11 followed in the late sixties by the salsa (hot sauce) music that was created in New York with its large Latino population. Salsa went on to influence American soul and R & B when Cuban congas were added to rock and funk bands, and there was a new Latin “bugalu” dance craze among the youth that went international.

The Latin tinge is reflected in a number of the Afrobeat songs Fela composed after 1970. One is “Jeun Ko’ku,” which opens with a Latin horn fanfare and utilizes a Caribbean clave rhythm. Other Latin and Latin-jazz-influenced songs are the mid-1970s “Water No Get Enemy,” “I No Get Eye For Back,” “Who No Know Go Know,” and “Na Poi.”

Despite the Spanish tinge in Fela’s music, his main musical direction in 1968 was highlife-jazz and soul.

This is what Johnny Opoku-Ayeampong has to say on the matter:

In 1968 he seemed to be looking for a new sound and had split the repertoire into the jazz highlife which we already knew, and something more soulish. So it was of two types, something called Afro-highlife and the other genre was dubbed Afro-soul. For me the Afro-highlife was only slightly different from the Afro-soul, which I preferred because it was less jazzy, less highlifish, and perhaps a bit more danceable—though not quite as funky as the American soul which by then had literally taking over most of our mixed repertoire at the time. It could have been deliberate as throughout all his music, one could detect that he wanted to be different, but it was quite subtle in those days. Also I think the Afro-soul was mostly sung in English or pidgin and the Afro-highlife mostly in Yoruba. Musically I did not immediately warm up to him because for most of us teenage musicians horns and highlife were not exciting and challenging enough. Also we had no horn players in our midst and other horn players around were older, too formal in their approach and would only play in B♭, C#, etc.—which was a pain for the average guitarist. We were then doing all the horn parts on the guitars until we progressed to the organ, mainly due to the advent of the Heartbeats influence [resident in Ghana 1964–68]. However at the gig at the Lido Fela played alone on the piano—a jazzy bluesy piece which suddenly gained my utmost respect and admiration.

Opoku-Akyeampong did not see Fela play again until early 1971 when Fela came to Ghana again and did one of his shows at the Labadi Pleasure Beach in Accra. By this time the Fela’s band was called the Africa 70, the soul and funk influence was more pronounced, and Afrobeat had crystallized. According to Opoku-Akyeampong Fela had by then become so popular that there were huge crowds at the event, and here he describes the music.

One thing which struck me after absorbing the early music was the undeniable influence of James Brown, like his danceable 1967 “Cold Sweat” single and albums which I loved that he released in 1968–69. That’s where Fela got his rhythm section, [where] the bass, drums, and guitars came from. Perhaps Fela “Africanized” it the more with the percussion, but the rest was all his own creation. Of course none of this detracts from this great man’s musical genius. If anything it is a true testament to his creativity, and I wish he had acknowledged it as such…. Again Fela accidentally coinvented jazz-funk. No one but James Brown had attempted anything quite like that before ’71. And I don’t recall J. B. doing anymore of those instrumentals. But I must be careful here to say that Booker T. and the M.G.’s also did some inspiring dance instrumentals even before 1971, but they were not jazz oriented as such. But the rest of jazz-funk proliferated with Grover Washington and the others throughout the 1970s.

Soul, Funk, and Crossover Sounds

In the late 1960s new outside musical influences began to affect Fela’s music. Soul music, and the associated Afro fashion, was introduced to Nigeria in 1966 by the Heartbeats band of Sierra Leone12 led by Geraldo Pino (Gerald Pine). A period of experimentation took place between 1967 and 1969, with Lagos artists such as Fela, Segun Bucknor, and Orlando Julius creating various blends of Afro-soul. Orlando changed the name of his highlife band to the Afro Sounders in 1967, while Segun changed his band’s name from Soul Assembly to Revolution in 1969. Fela was experimenting with soulish songs like “My Baby Don’t Love Me,” “Everyday I Got My Blues,” and also “Home Cooking” in which he actually uses the word “Afrobeat.”

It is likely that is was in 1968 that Fela started to call this new style that combined highlife, jazz, salsa, and soul “Afrobeat” and launched it at the Kakadu Club, which that year he began to call his Afro-Spot.13 According to the 1982 interview with Fela by Carlos Moore,14 Fela coined the name Afrobeat to distinguish his sound from the soulish sound of Geraldo Pino, whose Heartbeats were very big in Nigeria at the time.15 Again, according to Carlos Moore, Fela was in a club in Accra listening to James Brown’s soul music on a record player in 1968 with the Ghanaian/Nigerian music producer Raymond Aziz when he invented the name.16 Incidentally, it was only in 1970 that James Brown actually played in Africa—when he toured Nigeria in December of that year.

Although Fela’s Afrobeat was beginning to emerge by the late sixties, its lyrics were not at first so politically and socially confrontational as they were to become later. Fela’s politicization and radicalization was accelerated when he went to the United States in August 1969 for ten months.

Sandra Iszadore began Fela’s political radicalization and collaborated with him musically.

While there he and his eight-strong Koola Lobotis group made a record called “Keep Nigeria One,” a patriotic song that supported the federal government during the 1967–70 Nigerian Civil War. He also met the African American singer Sandra Iszadore (Smith) at a show of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Los Angeles. Sandra was associated with the militant Black Panther movement of Stokely Carmichael and others, and she gave Fela The Autobiography of Malcolm X to read. It was then that Fela began to be “exposed to African history,” as he puts it. It was in the United States that his first real Afrobeat style—influenced by both soul-funk and modal jazz—came together. It was also while in Los Angeles that he began to call his band Nigeria 70.

The Africa Shrine, Africa 70, and Anikulapo-Kuti Are Born

Fela returned to Nigeria in 1970 with his new Afrobeat sound, and at first he and his Nigeria 70 band continued operating his Afro-Spot club at the Kakudu Club. This is a description of how the musician Tee Mac Omatshola first encountered Fela and his club at that time.17

My mother, Suzanna Iseli Fregene Omateye, had the exclusive hairdressing Salon Bolaji, and I just returned from Switzerland having obtained a degree in economics and a master’s degree in the flute. I took up a job with UTC (a Swiss department store group in Lagos) and was just forming the Afro Collection.18 I went from the UTC head office every lunchtime to my mother’s salon to eat some food. So in August 1970 I went there on a Friday and saw a slim gentleman sitting there. My mother introduced me to him as the son of her good friend Mrs. Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti who was the first Nigerian lady to drive a car (and my mother was the second). She told me that her girls were doing the hair for Fela’s wife, and so I sat beside of Fela and we talked. I told him that I studied classical music in Switzerland and France and he told me that he is playing Afrobeat and jazz. He invited me to come to his Afro-Spot club next evening where his manager Felix received me. I was taken to Fela’s dressing room filled with girls. Fela sat there with a big joint in his mouth; it smelled bad and I asked him what the hell he was smoking! He said, “Natural Nigerian grass!” I joined him on stage [later] with my flute and I had the feeling that my fingers were playing on their own. Fela and the band loved my performance and I played many more times with him in the next twenty years.

I should add that Sandra Iszadore briefly joined Fela in Lagos in 1970. In fact he even made one song with Iszadore on a later trip by her called “Upside Down” that was released by Decca West Africa in 1976. This is about a man who travels the world where the telephones, light supply, transport system, etc. all work in an orderly way. However, when he comes back to Africa he sees plenty of land but no food, plenty of villages but no roads, plenty of open space but no houses. In short, education, agriculture, communications, and the power supply are in confusion. Fela’s reference to electrical failures is a quip on the state of NEPA, the Nigerian Electrical Supply Authority, which in the 1970s broke down ten to twenty times a day.

It was in 1971 that Fela moved from the Kakadu Club to the larger Surulere Club, changed the name of his band from the Nigeria 70 to the Africa 70, and renamed his Afro-Spot venue the Africa Shrine, which included a small shrine. By this time he had developed the idea of his “comprehensive show” in which his band would take a break in the middle of the dance set, change into animal skins, and return to play a floor show that included dancing and funny novelty acts. According to the band’s hand-drummer Daniel “J. B.” Koranteng, Fela wore a costume made out of snakeskin, another musician a leopard skin, while J. B. himself wore one made from a lion skin.

In 1971 Fela teamed up with Ginger Baker (formerly with Eric Clapton’s band Cream). The British rock drummer had crossed the Sahara Desert that year and made a film of the journey,19 as well as making a visit to Ghana’s veteran master drummer Kofi Ghanaba (Guy Warren). Baker subsequently went into partnership with a Nigerian and helped set up Nigeria’s first multitrack studio, ARC Studio

During the summer of 1971 the Africa 70 played in London with Ginger Baker at the Abbey Road Studios in London to record the album Fela Live with Ginger Baker. It was there that Fela first met Paul McCartney, who later, in 1973, was to visit Lagos on a recording trip with his band Wings and who got into a confrontation with and Fela at the Afro-Spot club in Lagos when Fela accused McCartney of trying to steal or woo away some members of the Africa 70.20

In London the Africa 70 played at the Cue Club, the Four Aces, and 100 Club and also toured the country. “J. B.” Koranteng told me that when they played in Wales and the band marched up to the stage for their “comprehensive show” section of the performance dressed in animal skins, the crowd panicked. Some started rushing for the door and others tried to jump out of windows, until Ginger Baker cooled them down and explained it was all part of the show.

It was in 1972 that Fela released his much-loved Yoruba Afrobeat “Sakara Oleje” about loudmouthed braggarts. That was also the year that the Africa 70 toured Ghana in a program organized by Stan Plange and Faisal Helwani. This included a performance for the leader Colonel Acheampong, as the new military government of Ghana was pro-Nkrumahist and still radical at that time. So Fela was quite comfortable performing for this military leader. Fela also played for and “yabbied” the university students at the Legon campus and the African Youth Command in Tema.

Fela talking to the Ghanaian military head of state Colonel Acheampong during a show in Accra in 1972.

In 1972 J. K. joined Fela after returning from abroad, and in late 1973 Fela relocated the Africa Shrine to the Empire Hotel in Mushin, diagonally opposite his house. There too he set up an actual shrine dedicated to Kwame Nkrumah and surrounded by the flags of some of Africa’s independent nations. By then the Africa 70 band was becoming more radical in its Yoruba and pidgin English lyrics, and between 1972 and 1974 the group began making extensive tours of West Africa. It was in 1975 that Fela Africanized his name by removing the colonial “Ransome” from his surname Ransome-Kuti and substituting it with “Anikulapo,” which means “he who holds death in his pocket or pouch.”