Читать книгу Fela - John Collins - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

THE KALAKUTA IS BORN

On April 30, 1974, the police raided Fela’s house, opposite the old Africa Shrine at the Empire Hotel, Mushin, and he was charged with possessing Indian hemp. In fact, he did have some on him, but he quickly swallowed it. Hemp was a term, incidentally, that Fela himself hated as he claimed that cannabis was not Indian. According to him it had been around in Africa for centuries, so he called it Nigerian natural grass, or NNG.

After the raid he was imprisoned for a while at the police CID headquarters at Alagbon Close. It was because the police examined his stools for traces of marijuana that he wrote the song about his “expensive shit” that was so interesting that doctors had to examine it with microscopes. As the note on the album cover says: “The men in uniform alleged I had swallowed a quantity of Indian Hemp. My shit was sent to lab for test. Result negative—which brings us to Expensive Shit.”

In fact he was never prosecuted, as the other prisoners would keep switching their buckets of feces with his, so the police could never find any evidence.

During this time at Alagbon Close he was locked in a cell the prisoners jokingly called the “Kalakuta Republic” (kalakuta is Swahili for “rascal”) and scratched this name on the cell wall. Because of Fela’s popularity with the downtrodden Lagosian underclass, or “sufferheads,” he was elected “president” of this “republic” by his jail mates. On his release he promptly named his house the Kalakuta Republic and brought out two albums whose lyrics dealt with his brush with the law. One was the above-mentioned Expensive Shit and the other Alagbon Close.

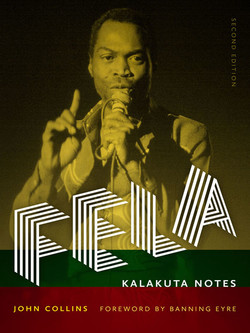

Fela yabbing to Lagosians outside the Africa Shrine on November 26, 1974, after his court acquittal.

On November 23, the same year, Fela’s house was attacked for the second time, this time because he was harboring a young runaway truant girl called Folake Oladende, who wanted to join his band. Her father was the inspector general of police for Lagos. The police officer claimed his daughter was only fourteen, and so under age. She claimed she was seventeen. After several fruitless attempts to get her back, the exasperated inspector general sent in the riot police, complete with metal helmets, shields, and tear-gas grenades.

By coincidence I was staying at the Africa Shrine that day, having just come to Lagos with two of Faisal Helwani’s bands, Basa-Basa and Bunzus, to record at the new eight-track EMI studio in Lagos. What follows is a journalistic account I made of that memorable eleven-day trip, written on my return to Ghana.

THE 23 NOVEMBER RAID

After a sixteen-hour journey to Lagos, a session at Victor Olaiya’s Papingo nightclub at the Stadium Hotel, and finally sleep at the Empire Hotel (Africa Shrine) Mushin, we were woken up on our first morning (23 November) by the roar of an angry crowd.

From our hotel balcony we could see about sixty riot police axing down Fela’s front door, just a hundred yards away. Fela’s people fought back, so then came the tear gas, and we Ghanaian musicians were down-wind!

We discovered later that he had refused to allow the police to make a routine search of his place and consequently suffered injuries to his head that needed nine stitches for his trouble.

According to the Nigerian Daily Times of 27 November: “Afrobeat King, Fela Ransome-Kuti, stepped into freedom from confinement again yesterday when the police granted him bail following his arrest after last Saturday’s police raid on his home.” The very same day he was released he had to appear in court, and the Times continued its report: “Fela was this morning discharged and acquitted by an Apapa Chief Magistrate’s Court on a three-count charge of unlawful possession of Indian hemp.”

That day we saw a happier demonstration from our balcony than the one on Saturday—after the court case a huge crowd followed Fela’s cavalcade to the Shrine, causing a massive go-slow of traffic.

The same night Fela played alongside Basa-Basa and the Bunzus, with one arm in a sling and wearing a skullcap that he humorously called a “pope’s hat.”

For the days Fela had been away his lawyer had sung the vocals and subsequently became known as “Feelings Lawyer,” as he made such a good substitute.

Faisal most certainly did the right thing when he decided to lodge us at the Shrine, the centre of the modern West African music scene. There we met Johnny Haastrup of Moro-Mono, who told us he was thinking of bringing his band to Ghana for a tour. Berkely Jones of BLO was around briefly and mentioned that he had recruited a new bass player. Big Joe Olodele, who used to be with the Black Santiagos in Ghana, is now with the Granadians—and Albert Jones from the Heartbeats ’72 was down from his base in Kano. And we had live Juju every night from the Lido nightclub opposite the hotel.

Our bands went down very well at the Papingo, where we played four nights alongside the resident All Stars (ex–Cool Cats). We then spent two days in the recording studio where Faisal and Fela were co-producing the session, and Faisal jammed on organ for some numbers. On 30 November we all departed, including the midget Kojo Tawiah Brown who came as our mascot, leaving Fela and Faisal to mix the recordings.

We were meant to play at the Cultural Centre in Cotonou, Dahomey [now the Republic of Benin], on our way back home, but we arrived the day the “People’s Revolution” was declared in Dahomey and found Cotonou deserted; everyone had gone to Abomé. We did, however, play the following night at the Centre Communitaire in Lomé, Togo.

We all learned a lot from our short stay in Nigeria. Fela is the top musician there, much more popular than foreign artists such as James Brown, or Jimmy Cliff, who was barely able to pull in a crowd of 6,000 at the 60,000-capacity football stadium at Surulere on 28 November. A lesson for Ghanaian pop fans, I think!

Bandaged but unbowed, Fela performs in what he called a “pope’s” or “alhaji’s hat” after returning from his court victory.

The entrance of the Africa Shrine in Mushin in 1974.

Five days after the November 23 attack Fela was released from jail and so was able to help Faisal coproduce the albums by Basa-Basa and the Bunzu Soundz. Fela also took over from Feelings Lawyer (Wole Kuboye) and played some of his current songs. One I recall was “Everything Scatter,” which praised African heroes such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Sékou Touré of Guinea, and, more controversially, General Idi Amin of Uganda. Fela insisted Amin was a heroic figure, settling scores with the Indian traders in his country and getting Europeans to carry him around in a palanquin. Another song that Fela was playing at this time was “Confusion,” released the following year, which is about the problems created for West African countries having multiple languages and currencies.

In 1976 Fela used his technique of turning confrontation with the authorities into music when he released for EMI his album Kalakuta Show, which describes the police attack on him on November 23, 1974.