Читать книгу Fela - John Collins - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

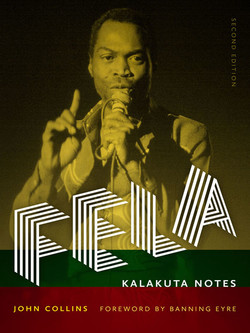

Fela Anikulapo-Kuti was Africa’s archetypal Pan-African protest singer whose lyrics condemned neocolonialism in general and the Nigerian authorities in particular. During his turbulent lifetime, and particularly since his death in 1997, this controversial Nigerian creator of Afrobeat and spokesman for the poor and downtrodden masses, or “sufferheads,” of Africa, has generated an enormous level of international interest. He has been the subject of many books and PhD dissertations and thousands of column inches of newsprint, both in Nigeria and elsewhere. In the mid-1980s he became an official “prisoner of conscience” of Amnesty International. Throughout his stormy career he has been the source of more wild and uninformed gossip than almost any musician of the twentieth century.

Fela, the “chief priest” of Afrobeat; the aspiring “Black President”; “Anikulapo,” who carries death in his pocket; “Abami Edo,” “the weird one and strange being,” died in Lagos aged fifty-eight on August 2, 1997. Fela did two remarkable and unique things in his life. First of all, he almost singlehandedly created Afrobeat, a major new genre of African popular music that is adored by fans throughout Africa and that has influenced numerous African and international musicians. Second, with his unsurpassed militancy, he took African music into the arena of direct political action; a fighting spirit reflected in his own contrary lifestyle and his catalogue of antiestablishment songs dedicated to Pan-Africanism and the Nigerian masses.

Fela was a musical warrior who drew heavily on age-old connections between music, militancy, and violence. Lyrically, his music dwelt on the confrontational aspects of life, from which he obtained enormous inspiration. Indeed, if there was not sufficient confrontation to inspire a song, he would create that confrontation first—a unique creative device that often resulted in direct battles with the Nigerian authorities. In his songs Fela went much farther than the oft-quoted pantheon of international protest singers such as Bob Dylan, James Brown, and Bob Marley. Whereas their confrontations with established authority were couched in terms of “The Times They Are A-Changin,”’ “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud,” and the evils of “Babylon,” Fela’s songs not only protested against various forms of injustice but often fiercely attacked specific agencies such as “Alagbon Close,” which mocked the police criminal investigation department (CID) headquarters in Lagos where Fela was imprisoned in 1974. His 1976 Zombie album was an insulting caricature of the Nigerian army mentality that became a battle cry across a continent that was plagued by military regimes at the time. Sometimes he named names. His song “Coffin for Head of State” was directed against Nigeria’s then military ruler (and later civilian president) General Olusegun Obasanjo. “International Thief Thief (ITT)” criticized the US multinational company, International Telephone & Telegraph Corporation, which set up a telecommunications system in Nigeria under Chief Moshood Abiola, who later stood for president of Nigeria.

As the dust settles over Fela’s fiery, promiscuous, rascally, and egoistic lifestyle, his Afrobeat groove lives on. He will always be remembered as the most radical musical spokesman of the African poor. His peppery character in the African soup continues to be sorely missed.

Fela’s Family Background in Abeokuta

Fela was born on October 15, 1938, in Abeokuta, a Yoruba town about fifty miles north of Lagos that is famous for its natural fortress, Abeokuta Rock.

Fela’s birth name was Olufela Olusegun Oludotun Ransome-Kuti. His older sister was Oludulopa, or Dolu, who became a nurse, and his older and younger brothers were Olikoye and Bekolari, who both became medical doctors. The famous poet-novelist and Nobel Prize laureate Wole Soyinka was Fela’s cousin and was also raised in Abeokuta.

Fela’s maternal grandfather was Pastor Thomas, a Yoruba slave freed in Sierra Leone. Fela’s paternal grandfather was the Anglican priest, the Reverend J. J. Ransome-Kuti, a principal figure in the Christianization of the Yoruba who was also a pianist and composed many Yoruba hymns and patriotic anthems. Forty-four of these were recorded by the Zonophone/EMI company of Britain in the mid-1920s, and these included sacred songs with piano, two funeral laments, and two patriotic songs with piano—one being the Abeokuta National Anthem “K’Olurun Da Oba Si.”1 Fela’s father was the Anglican Reverend Oludotun Ransome-Kuti, a schoolteacher, music tutor, and a strict disciplinarian who became headmaster of the Abeokuta Grammar School that the young Fela attended and from where he obtained his music skills.

Besides the local hymns and Western-type music training coming from Fela’s father and grandfather, Fela was, as a youth, also exposed to other musical forms prominent in Abeokuta at the time, such as Yoruba juju guitar-band music, Yoruba-Muslim sakara and apala popular-music styles, and the deeper Yoruba drum and dance music of the Egungun and Gelede masquerade cults that were dedicated to the ancestors and fertility.

Fela’s mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti (née Thomas), was a nationalist and women’s rights activist. In 1947–48 Funmilayo led a number of mass demonstrations of local Egba market women who opposed the British-instigated plan of taxing them via the alake (king) of Abeokuta, Olapado Ademola. Their demonstrations were successful, and these events are captured in Wole Soyinka’s autobiographical novel Ake: Years of Childhood.2 Shortly after, Fela’s mother went on to found the Nigerian Women’s Union and then became an executive of the Women’s International Democratic Federation, and in this capacity visited Moscow, Eastern Europe, and Beijing between 1953 and 1961.3 She met Mao Zedong, was the first Nigerian woman to visit Russia, where she received the Lenin Peace Prize, and was the first woman to drive a car in Nigeria. When the country became independent in 1960 she became one of Nigeria’s few women chiefs. Funmilayo was also a supporter of one of the leading figures of modern Nigerian nationalism, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, or “Zik,” and her nationalist inclinations also resulted in her (and also Fela) meeting Nkrumah, for instance, when the Ghanaian leader made trip to Lagos by boat in 1957.4

Fela’s younger brother, Dr. Beko Ransome-Kuti, also inherited his mother’s radical streak. During the 1970s Beko was running his free Junction Clinic for the poor of Mushin at Fela’s Kalakuta Republic, which, in fact, was their mother’s Lagos house. Beko was also the general secretary of the radical Nigerian Medical Association, and after the burning of the Kalakuta and his clinic by the Nigerian army in 1977 he was radicalized and became chairman of the Nigerian Campaign for Democracy and so was imprisoned from 1995 to 1998. This was during the brutal Abacha military regime when Fela was also imprisoned on several occasions.

Fela’s Musical Background: Highlife, Jazz, and Soul

By 1954 Fela had completed his primary education at his father’s school and for four years attended the Abeokuta Secondary School. In 1955 Fela’s father died, and so Fela began making occasional trips to Lagos where he became friends with Jimo Kombi, or “J. K.,” Braimah, who finished school in 1956, became a clerk in a Lagos court, and in his spare time sang for various highlife dance bands in Lagos. One of these was Victor Olaiya’s Cool Cats, and the precocious Fela sometimes accompanied him to these shows. After the death of Fela’s father, his mother relocated to the family house at 14A Agege Motor Road, Surulere (which later became the Kalakuta Republic). By 1957 Fela had finished his schooling and so went to stay with his mother in Lagos and work there in a government commercial industry office. It was at this time Fela joined Olaiya’s band as a singer who, in turn had been influenced in the 1950s by Ghana’s pioneering highlife dance-band musician E. T. Mensah, who took his Tempos dance band on numerous tours of Nigeria beginning in 1951.

Victor Olaiya’s highlife band around 1960. Fela sang with them occasionally in the 1950s. Olaiya is in the center of the picture on trumpet.

Nigerian highlife itself originally came from Ghana in three waves. First was the 1938 Nigerian tour of the Cape Coast Sugar Babies dance orchestra; this was followed by the low-class konkoma (konkomba) form of highlife brought by Ghanaian migrant workers that did away with expensive Western instruments by using local percussion and voices; and finally the 1950 tours by the Tempos dance band that will be referred to again below.

Although the term “highlife” was not coined in Ghana until the early to mid-1920s, the origins of it go back much earlier. In the late nineteenth century British-trained Ghanaian regimental brass-band musicians at Cape Coast and El Mina Castle began creating their own syncopated and polyphonic style of brass-band music, with the catalyst being the 5,000 to 7,000 West Indian soldiers who were stationed at these castle forts during the Ashanti Wars of 1873–1901. The Afro-Caribbean tunes and syncopated rhythms that these colonial black troops from the English-speaking Caribbean played in their spare time provided an alternative model of brass-band music, as compared to the British marching songs done in strict time. As a result, coastal African brass musicians first copied Afro-Caribbean rhythms and melodies and then, within ten years or so, went on to invent a proto-form of highlife called adaha music in the 1880s.

Around the same time, African sailors (and in particular the coastal Kru or Croo of Liberia) employed on British and American ships during the nineteenth century adopted sailors’ instruments and on the high seas created a distinct African way of playing the guitar that they spread down the western and central African coast. These guitar techniques fed into the emerging popular “palm-wine” guitar music of Sierra Leone (Krio maringa music), Ghana (Fanti osibisaaba), and Nigeria (Yoruba juju music).

Juju music itself was a fusion of sailors’ palm-wine guitar music, Sierra Leone derived ashiko music and local “native blues,” and Yoruba praise singing. It first appeared in Lagos and Ibadan in the 1930s and was pioneered by the likes of Tunde King and Ayinde Bakere. Later Bakere and Akanbi Ege Wright introduced amplified guitars, and during the 1950s to 1970s this guitar-band music was developed by Tunde Nightingale, I. K. Dairo, Ebenezer Obey, Sunny Adé, and others.5

The word highlife emerged in Ghana after 1914, when many ballroom-dance orchestras were set up by and for the local elites; these included the Excelsior Orchestra, the Jazz Kings, the Accra Orchestra, and the Cape Coast Sugar Babies. At first these musicians did not play local music, but by the early 1920s they began to orchestrate some of the adaha, osibisaaba, and other local street songs. In fact, the name “highlife” was coined not by the well-to-do performers and audiences of these prestigious orchestras but rather by the poor who gathered outside for free shows on the nearby streets and pavements: the sailors, fishermen, ex-soldiers, migrants, and area boys who were the original purveyors, and audiences for, the existing forms of local popular music.6

Cape Coast Sugar Babies Orchestra and fans in Enugu in 1938.

British officer training a Gold Coast marching band in the early 1900s.

The Ghanaian Kumasi Trio guitar band in 1928, composed of three Fanti musicians based in Kumasi. The leader, Kwame Asare (a.k.a. Jacob Sam), is on the right.

Juju band at Lido nightclub opposite the old Africa Shrine, 1974.

Tempos band with its leader E. T. Mensah seated in the middle.

During the Second World War Allied troops were stationed in many African countries and they brought swing-jazz records with them. In Ghana this resulted in a new type of highlife band modeled on a small swing combo that replaced the earlier large and mostly symphony-like ballroom-dance orchestras. It was the wartime Tempos dance band that pioneered this development.

The Tempos initially consisted of Ghanaians and white army musicians who played swing for the thousands of Allied troops stationed in Ghana between 1939 and 1945. But when the white soldiers left, the Tempos survived as an all-Ghanaian band, and under the leadership of Kofi Ghanaba (Guy Warren), and then E. T. Mensah, this outfit made the breakthrough into a new sound, which fused highlife music with jazz, calypso, and Latin music. By the early fifties other dance bands modeled on the Tempos were appearing in Ghana, such as the Red Spots, Joe Kelly’s Band, the Rhythm Aces, and Black Beats. In 1951 the Tempos, now under the leadership of E. T. Mensah, made their first trip to Nigeria.

It was largely through the 1950s tours of the Tempos that highlife dance-band music spread from Ghana to Nigeria. There musicians like Bobby Benson, Rex Lawson, Victor Olaiya, Bill Friday, Roy Chicago, Eddie Okonta, and Zeal Onyia quickly Nigerianized highlife, which became entrenched in western, midwestern, and southeastern Nigeria.

All this development of dance-band highlife in Ghana and Nigeria was going on in the early fifties and was being put together by young musicians who supported the independence struggle. As a result, their new sound that employed Western jazz instrumentation but played African music became the “sound symbol” or “sound track” for the early independence era of both of these two countries.

For instance, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah used highlife music for state and international functions, set up government highlife bands, and encouraged these bands to Africanize their music.7 On the eve of Nigeria’s independence in 1960 irate Nigerian musicians marched with their union through Lagos to demand that highlife be played at the National Independence Dance, rather than the planned performance by the British Edmundo Ross band. According to the Ghanaian guitarist Stan Plange,8 who was in Lagos then as guitarist with Bill Friday’s Downbeats band, almost a thousand members of the Nigerian musicians’ union marched from the Empire Hotel, Idioro, to Government House to petition the prime minister, Tafawa Balewa. He agreed that local highlife rather than imported Latin and swing music should be played. So local highlife artists such as Victor Olaiya, Zeal Onyia, and Chris Ajilo played at this important national event.

Bobby Benson and E. T. Mensah in the early 1950s.

During the 1960s Western pop music began to be picked up by the youth of Ghana, Nigeria, and other countries in Africa. First came rock ’n’ roll and the associated “twist” dance, followed by soul music of James Brown and Wilson Pickett. At first local artists simply copied this imported music. Rock bands in Ghana included the Avengers and Psychedelic Aliens; then from Gambia came the Super Eagles (led by Badou Jobe and Paps Touray); from Sierra Leone, Geraldo Pino’s Heartbeats (that included Francis Fuster); and from Nigeria, the Clusters, Segun Bucknor’s Hot Four, and Sonny Okosun’s Postmen. Local soul artists and bands included Elvis J. Brown, Pepe Dynamite, and Stanley Todd’s El Pollos of Ghana and the Hykkers and Tony Benson’s Strangers of Nigeria, with Joni Haastrup being acclaimed as Nigeria’s James Brown. Even earlier, in Sierra Leone, Pino’s Heartbeats switched from pop to soul music and became West Africa’s first homegrown soul band. They then promptly left Freetown for Ghana and then Nigeria, taking live performances of this black American dance music with them.

Geraldo Pino, leader of the

Sierra Leonian band The Heartbeats.

By the late 1960s there was a creative explosion among African musicians who had been influenced by rock and soul music introduced through records and films. First, early rock ’n’ roll and its associated twist dance became a craze with urban African youth. This was followed by the progressive and psychedelic rock music of the later Beatles, Eric Clapton’s Cream (that included the drummer Ginger Baker), Jimi Hendrix, Sly and the Family Stone, as well as the Latin-rock fusion of Santana—all of which fostered a more experimental spirit among young African pop musicians. Enhancing this impact on African musicians was that both Ginger Baker and Paul McCartney worked in Nigeria in 1971 and 1973, respectively, while Santana played in Ghana in 1971. At the same time soul music and its “funk” offshoot with their extended dance grooves and associated “Afro” fashions became the craze of urban African youth. Soul also spread an Afrocentric “roots” message as found, for instance, in the “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud” lyrics of James Brown. In fact his records became so popular that he and his J.B.’s band toured Nigeria in 1970.

As a result of the back-to-roots and innovative energy contained in these new forms of imported popular music, many young African artists who had been copying rock and soul music began to dig into their own indigenous musical resources and develop various new forms of Afropop music, such as Afro-rock, Afro-soul, Afro-funk, and Afrobeat. Afro-rock was created around 1969–70 by the London-based group Osibisa that included Ghanaian, West Indian, and Nigerian musicians and was led by three Ghanaian ex-highlife dance-band musicians: Mac Tonto, Sol Amarfio, and Teddy Osei.

Their international success encouraged numerous other Afro-rock bands that formed in the early and mid-1970s, such as South Africa’s Harare and Juluka (Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu), Thomas Mapfumo’s Hallelujah Chicken Run Band and Acid Band in Zimbabwe, Ebenezer Kojo Samuels’ Kapingbdi group in Liberia, and the Super Combo of Sierra Leone. In Ghana there was as Boombaya, the Zonglo Biiz, Hedzoleh, Basa-Basa, and the Bunzus. Nigeria saw the formation of Tee Macs Afro-Collection, BLO, Ofege, Sonny Okosun (his ozzidi style), Ofo and the Black Company, Mono Mono, and the Funkees.

Ghanaian dancer Tawia Brown (second from right) and friends at the Africa Shrine. For the Bunzus and Basa-Basa shows at the Africa Shrine and Papingo nightclub, Tawia Brown would do a floor show in between sets.

At roughly the same time that Afro-rock was emerging, different Africanized versions of soul, or “Afro-soul,” were appearing in many African countries. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo the guitarist Dr. Nico Kassandra released his popular soul number “Suki Shy Man” in 1969, the Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango released his “Soul Makossa” in 1972, and by 1974 Moses Ngenya’s and his Soul Brothers of South Africa were blending soul with local township mbaqanga music.

In Ghana there was the Afro-soul of the Magic Aliens, El Pollos, and Tommy Darling’s Wantu Wazuri, followed by the Afro-funk and funky highlifes of Ebo Taylor, Bob Pinodo, and Gyedu-Blay Amboley. Nigerian experimentations with Afro-soul music likewise began in the late 1960s and included those of the highlife guitarist Victor Uwaifo (his mutaba style), the highlife saxophonist Orlando Julius, the pop and soul musician Segun Bucknor—and of course the highlife musician Fela Kuti, who coined the term “Afrobeat” in 1968.

As will be discussed in this book, Fela actually combined a number of musical styles into his Afrobeat that, besides highlife and soul music, also include three other important ingredients. First there was jazz music, with Fela employing the modal jazz approach of artists such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane, who created melodies based on improvising around and moving between two modes or tone centers rather than following a single scale and strict chord changes. Incidentally, this use of modal melodies that move between two tones rather than following a Western-type chord progression (e.g., I–IV–V) away from and back to a single tone center, makes modal jazz rather similar to African traditional music. As such, Afrobeat created a convergence between modal jazz and African music. Another jazz feature found in Afrobeat is that its rhythmic basis was created by the half Ghanaian–half Nigerian trap drummer Tony Allen, who played in a modern-jazz style—moving away from simply providing regular dance rhythms to also including improvisations, polyrhythmic high-hat pulses, and offbeat accents that supplied rhythmic space and ventilation for the dance groove. Allen also developed the double bass-drum technique so distinctive of his Afrobeat style in which he does a double kick on the bass pedal a sixteenth note apart, which usually falls right at the beginning of the four-bar measure and propels the rhythm emphatically forward.

Besides highlife, soul, and jazz, another source that Fela drew on for his Afrobeat was traditional Yoruba music making, which included the modal melodic movements already mentioned as well as other traditional features such as call-and-response between chorus and singer/soloist and the use of a pentatonic singing style that Fela blended in with the minor blues scale. These traditional elements were enhanced by Fela’s adding two hand drums to his ensemble around 1970–71.

The last ingredient of Afrobeat was that Fela often gave his compositions a Latin touch. This was partly a result of the long-term impact from the 1930s of Afro-Cuban (later called salsa) music on West African dance-band musicians. But also important was the presence from the late nineteenth century of many thousands of freed Brazilian slaves (Aguda people) who brought their samba music and masquerades with them—and which became part of the Lagos musical landscape. Indeed, current Felabrations in Lagos that commemorate Fela’s birthday include a carnival parade that draws on this Brazilian heritage.

Fela began experimenting with his new Afrobeat style in the late 1960s with his Koola Lobitos band, but really put the sound together when he was in the United States in 1969–70. It was also there he changed the name of his group to Nigeria 70, and on returning to Nigeria changed it yet again to Africa 70. His Afrobeat spread far and wide and influenced many African artists and bands. There was the Poly-Rhythmic Orchestra of Cotonu in the Benin Republic, the music of the South African jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela, and the Big Beats, Sawaaba Sounds, and Nana Ampadu’s African Brothers (with his “Afrohili” style of guitar-band music) in Ghana. In Nigeria there were the Lijadu Sisters and the Hausa Afrobeat of Bala Miller’s Northern Pyramids.

In Nigeria a number of Yoruba juju-music guitar-band artists were also influenced in the early to mid-1970s by Fela’s Afrobeat—and these included Pick Peters, Prince Adekunle, and Sunny Adé with his “synchro system” style.

Emmanuel Odunesu of the EMI Studio in Lagos.

Fela’s Political Background: Nkrumah and the Early Independence Era of Ghana and Nigeria

Fela was born one year before the outbreak of the Second World War during which Africa supplied raw materials and about 300,000 soldiers to the Allied war effort. The war weakened the British and French, and as a result their colonies were granted independence, beginning with British India in 1948, followed by Caribbean and African countries during the late fifties and sixties.

The first African country to gain independence was Ghana in 1957, and the preceding nationalist upsurge was triggered by a peaceful demonstration in 1948 of Ghanaian ex-servicemen who had fought in the British army in Burma and the Far East against the Japanese9 and were demanding back pay. Several were shot, and this resulted in widespread rioting and the looting of European shops. The British lost their colonial nerve and allowed elections to be held in 1952. Despite the fact that the British had jailed the radical Ghanaian nationalist Kwame Nkrumah who wanted independence “now,” he won the election—and the country was given internal self-rule in 1952 and full independence in 1957. Ghanaian independence was followed by the independence of Guinea from France in 1958, and Nkrumah helped its new president Sékou Touré after the French had wrecked the country in a fit of pique when it had dared to say non to General de Gaulle’s referendum on retaining close ties with France.10

Like Ghana, Nigeria supplied raw materials and soldiers for the British war effort; in fact over, half of the 100,000 Anglophone West African soldiers who fought in Burma were Nigerian—where they became known as “boma boys.”11 Also like Ghana, Nigeria had a tradition of anticolonial activists, for instance, the previously mentioned Nnamdi “Zik” Azikiwe who, like Nkrumah, attended university in the United States. Following his studies (in 1934), Azikiwe became the editor for the African Morning Post of Accra, Ghana. But when he was imprisoned for publishing what the British thought to be a seditious article, he returned to Nigeria in 1937 where he founded the West African Pilot newspaper that fostered Nigerian nationalism.

Also like Ghana, Nigeria had been radicalized by the war, and this growing militancy was evidenced in 1945 by two developments. That year Zik and Herbert Macaulay founded the independence party called the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) that Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti supported. Second, there were a number of big strikes that year by Nigerian workers. There was a general strike led by the Nigerian Trade Union Congress (led by Michael Imoudu) that involved tens of thousands of railway, transport, dock, and civil service workers. Nigerian popular artists of the times even became involved in this dispute, such as the leader of the Nigerian popular theater movement, Hubert Ogunde, who produced the sensational play, Strike and Hunger. Ogunde would eventually be arrested on charges of sedition for his play Bread and Bullets about the 1950 Enugu coal strike.12

By the 1950s there were three main political parties operating in Nigeria that were demanding independence: Azikiwe’s (NCNC) had control of the Eastern Region government; the Northern Peoples Congress (NPC) centered on the Northern Region; and the Action Group (AG) was based in the Yoruba Western Region. Internal self-rule was granted in the late 1950s, and in October 1960 the country obtained full independence as the Federation of Nigeria. The first government was an alliance of the eastern-based NCNC and the northern NPC, with Abubakar Tafawa Balewa as Nigeria’s first prime minister and Azikiwe as the governor-general. When Nigeria declared itself a Republic in 1963, Azikiwe would become the country’s first president, serving until 1966 when the first of many military coups took place in Nigeria.

During these years, when Fela and the Koola Lobitos were playing in Lagos, the city was the highlife hub for both eastern and western Nigerian highlife musicians. After the 1967–70 Nigerian Civil War, many Igbo and other eastern Nigerian highlife musicians and bands relocated to the east.

Fela was also influenced by the recorded music (and occasional trips to Nigeria) by Ghanaian highlife dance bands such as the Tempos, who in the early sixties became closely associated with the great Pan-African thinker Kwame Nkrumah. Furthermore, from the late 1960s onward, Fela made numerous trips to Ghana where he was particularly impressed by the music of the Uhuru big band, sometimes stayed at their premises in Accra—and at one point in his early career even thought of relocating to Ghana.

Ghana was the first West African country to become independent, it was home to Kwame Nkrumah, and it was the birthplace of highlife—it’s easy to see how Fela became such a Ghanaphile. When Fela later became politically conscious he became an Nkrumahist. Indeed, he constructed a Pan-African shrine in the early 1970s at his Africa Shrine Club that was centered on images of Nkrumah.

My Encounters with Fela

It was around 1970 or ’71 that I first heard Fela’s songs “Mister Who Are You?” and “Jeun K’oku” (also called “Chop and Quench”) from singles friends brought back from Nigeria to Ghana. However, it was only in 1972 that I first saw him play when I was a student at the University of Ghana at Legon and he and his Africa 70 band played at the university cafeteria, with Fela on keyboards and tenor saxophone.

Then in November 1974 I played for a week in Lagos with the Ghanaian Bunzus Band at Fela’s Africa Shrine Club and Victor Olaiya’s Papingo Nightclub. During this time, the police raided the old Kalakuta Republic. After his acquittal Fela assisted us in the recordings that we and our sister band Basa-Basa and our manager Faisal Helwani were making at the at the EMI studio in Lagos.

In December 1975 I again met Fela in Lagos when I was on my way to Benin City to work with and write about the highlife musician Victor Uwaifo. I interviewed Fela on this occasion. This was probably around the time that Fela began discussing with the Ghanaian poet and screenwriter Alex Oduro the possibility of making a film of Fela’s life.

Early in 1976 I met Fela several times in Ghana when he came to Accra to play at Helwani’s Napoleon Club jazz jam-session nights. On these trips Fela did his “yabbis” for the university students, telling them how the Western world had deliberately hidden the long history of Africa. He called these sessions “Who No Know Go Know” after his 1975 album of that name.

In June 1976 Fela returned to Ghana to plan “The Black President” film, in which I played a British colonial education inspector. It was in December 1976 that Fela arrived in Ghana to begin the actual shooting of the film, and it was on this occasion that I introduced him to the famous Ghanaian guitar-band highlife musician E. K. Nyame, whose songs had been popular in Nigeria when Fela was young.

Basa-Basa guys and bus in between Accra and Lagos. The Basa-Basa band went with the Bunzus band to Nigeria to play and record.

Poster for a Fela show at the Napoleon Club jazz night, 1976.

I spent the month of January 1977 in Nigeria acting in “The Black President,” and during this trip I met Fela’s wife, Remi, his mother, Funmilayo, his sister, Dolu, his brother Beko, and his three children: Yeni, Femi, and Sola. Later that year and also in 1978, I met Fela several times when he was going back and forth between Accra and Lagos doing the overdubs of the destroyed sound track of “The Black President” film at the Ghana Film Studio in Accra.

In 1981 I met Fela and his Egypt 80 band in Holland at the Amsterdam Woods summer festival and later took a group of Dutch journalists to meet him at his hotel. He had just released his album International Thief Thief (ITT).

A Note on Sources

In addition to my own reminiscences, diaries, journalistic works, and interviews, this book also draws on Ghanaian and Nigerian newspapers. I conducted an interview with Fela in 1975. The two interviews with Faisal Helwani were shortly after Fela’s death. I also enjoyed long conversations with two eminent Ghanaian musicians, Stan Plange and Joe Mensah, both of whom knew Fela intimately in his early days. I spoke to George Gardner, Fela’s Ghanaian lawyer during the late 1970s. Fela employed several Ghanaian musicians in his band, and I have included an important interview with his 1970s conga player, “J. B.” Koranteng, as well as Fela’s 1980s’ percussionists Frank Siisi-Yoyo and Obiba Sly Collins. Nigerians I talked to include Fela’s lifelong friend J. K. Braimah; the musicologist Meki Nzewi; the Afro-fusion artist Tee Mac Omatshola; Smart Binete, who organized Fela’s last Ghanaian tour; and the percussionist Bayo Martins, who at one point in the early 1960s played with Fela. I interviewed the Ghanaian musicians Mac Tontoh of the Uhuru highlife dance band (later the Osibisa Afro-rock band), and Nana Danso, whose Pan-African Orchestra includes instrumental versions of some of Fela’s songs—as well communicating with Johnny Opoku Akyeampong (Jon C. G. N. Goldy) and Alfred “Kari” Bannerman, who worked alongside Fela in the late 1960s. I also interviewed the late Professor Willie Anku of the University of Ghana, who has transcribed several of Fela’s songs.

For additional context I have included some comments by the Ghanaian drummer Kofi Ghanaba (Guy Warren), who as early as the 1950s and ’60s was producing his own distinct style of Afro-jazz, and the Nigerian keyboard player Segun Bucknor, who created a form of Afro-soul in the late 1960s.