Читать книгу Fela - John Collins - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

“J. B.” TALKS ABOUT FELA

Daniel Koranteng, better known as “J. B.,” was one of Fela’s conga players between 1971 and early 1975. He is half Ga, half Fanti, and was born in the Accra Police Depot in 1948. I interviewed him at the music department of the University of Ghana, Legon, on May 11, 1999. As he explains, although he did not start playing congas for Fela until April 1971, he danced for him much earlier.

How did you meet Fela?

Fela came to Ghana in 1967, and at that time I was playing drums for a traditional Ga kpanlogo group called Play and Laugh and was the soul dancer for the Bugulu Dance Group of Accra Newtown. I was a fantastic soul dancer, and so was called J. B., or James Brown. The dance group played at the Pan African Hotel, Grand Hotel, Tip Toe Gardens, Lido—and anywhere where there were bands that could play soul; like the El Pollos, Barbecues, Uhurus, Geraldo Pino’s Heartbeats [a Sierra Leonean band] and the Black Santiagos led by Ignace de Souza from the Benin Republic. Fela and his Koola Lobitos band came with a beautiful Nigerian lady dancer called Dele and they all stayed at the Pan African Hotel. Fela normally played side by side with the Uhurus, and as the Bugulu dancers used to perform with them we also performed with Dele. I loved the way Fela held his trumpet, he turned it sideways and played Yoruba highlife like “Ashe Love” in a jazzy way.

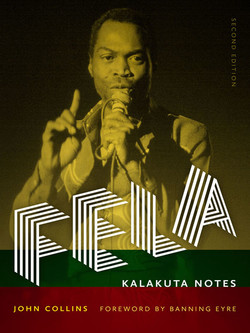

Fela with Africa 70. Daniel “J. B.” Koranteng is standing second from right.

When was the next time you met Fela?

It was in Lagos. You see there was an Al Hadji who lived in Accra Newtown who heard in 1969 that Geraldo Pino and later the El Pollos were making it in Nigeria with the James Brown thing. The Al Hadji was managing a soul group called the Triffis led by Lindy Lee [Lord Lindon], and he wanted to take me as well. Later, in December 1969, when we were in the north of Nigeria, we heard that thousands of Nigerians were being repatriated from Ghana [during President Busia’s infamous Aliens’ Compliance Order]. So we changed our name to the Big Beats [that later recorded the famous Ghanaian Afrobeat song “Kyenkyemma,” which means “decrepit” or “old-fashioned”].

I then joined a Lagos soul group called the Immortals, playing jazz drums that sometimes played at the Kakadu Nightclub in Yaba, which Fela renamed the Afro-Spot when he came back from the United States in 1969.1 So Fela asked me to dance with Dele for the Nigeria 70 on a permanent basis and paid me five pounds a week. Six months later two black American music students came to the Afro-Spot to feature on conga drums with Fela’s band, then called Nigeria 70. It was marvelous. The following day Fela asked me that “Do you know anyone who can play congas because I want to infuse these two congas into my Afrobeat.” I told him that I played congas myself. Fela said I should go and look for another person, and I got Friday Jombo [or Jumbo], who played congas with Peter King’s Voices of Africa band. The first time we played double rhythm congas for Fela was Tuesday, April 9, 1971, and it was also the first ladies’ night [women got in free] at the Afro-Spot.

Three months later we toured England and recorded at the Abbey Road multitrack studio Fela Live with Ginger Baker, with Ginger Baker and Tony Allen doing drum solos. We played in clubs in London like the West End, Countdown, and Speakeasy and then went to Wales and Kessington where Ginger Baker comes from. We also met Paul and Linda McCartney and the other members of the Beatles who also recorded at Abbey Road.

Was there not some trouble between Fela and Paul McCartney?

This was the following year [actually in August 1973] when Paul McCartney and his new band Wings came to Nigeria and visited Fela at his new Afro-Spot club in Surulere—before he used the name Africa Shrine. Some of Fela’s musicians were taken by McCartney to help record the Wings album [Band on the Run] without Fela’s permission.2 They employed the horns-men, guitarists, and bass player. Fela is a jealous man and told [backstage]—I believe it was McCartney at the Afro-Spot: “Man you can’t do that to me, do you want to spoil my band, you should have taken permission from me.”3

I believe it was in 1972 that you toured Ghana with Fela?

Yes, we went there in February 1972 when Colonel Acheampong took over from the civilian Busia government. We were actually in Accra when the military coup took place. On that tour we were playing “Open and Close,” “Who Are You,” “Fight Finish,” “Chop and Quench,” and “Je-Je” and we performed at the Apollo Theatre, Tip Toe Gardens, and the university campus in Accra; and also in Takoradi, Cape Coast, and Kumasi. We also played at the officers’ mess at State House for Colonel Acheampong. He was very happy to see me, a Ghanaian, playing in Fela’s group. It was on that Ghanaian tour that Fela got the idea for his “Shakara” and “Lady” tunes. He went to lodge at the Presidential Hotel in Accra and asked the receptionist: “Woman, how do I book my lodging?” She said: “Please, I’m not a woman, I’m a lady.” She was bluffing. So Fela composed the two songs when he got back to Nigeria.

Were you the only Ghanaian musician in Fela’s band at that time?

No. There was Peter Kadana from the north of Ghana who played guitar and later changed his name to Rescole. Then there was Henry Kofi, who was half Ghanaian and half Nigerian and played the triple lead congas. And the drummer Tony Allen, who is half Nigerian and half Ghanaian Ewe. Also a bit later the Ghanaian Nicholas Addo replaced Friday Jombo on the rhythm conga.

When was it that Fela began to get into trouble with the authorities?

It was from the end of 1973 when Fela had changed the name of his club to the Africa Shrine (still in Surulere). There was a judge’s daughter who came to the afternoon jump when she was on school holidays and followed Fela and wouldn’t go home. Then there was a police commissioner’s daughter who came to the Shrine and also went to live at Fela’s house [his mother’s house in Mushin later called the Kalakuta]. So the parents of these girls sent some brothers to call their sisters. Fela beat one of the brothers and put out a burning cigarette on his skin. Fela told them that if you know your sister is missing go to the police and report—don’t come here. So the parents sent policemen and policewomen with dogs to arrest anyone they see at Fela’s house. This was in April 1974.

I had gone there to collect money to repair my conga drum. The police first sent two officers inside the house and told Fela they were coming to search for Indian hemp and the two missing girls. Fela told them that before you come into my house I will first search you as you may be coming in with drugs to put in my house to put me into trouble. So Fela searched the two officers up and down and found a talisman in one of the policeman’s pockets.

Fela asked him what he is doing with a talisman and the officer said we use it for protection. So after a long argument Fela said you can all come in—by which time everything had been put in order and the two girls had gone through the back door and jumped the fence. So the police couldn’t catch either of them but rather arrested we who had come innocently, and the musicians and girl dancers living there—fifty-two of us in all—and took us to CID headquarters at Alagbon Close.

They also arrested Fela, saying that he was smoking Indian hemp and took him to a cell at Alagbon Close where they keep all the political detainees, eminent personalities, veteran soldiers, and military officers who had been arrested during the [Biafran] civil war. This area of the prison is called “XX Timbuctu” and has only one door and no proper windows. So the moment Fela entered, these people shouted: “Fela, Fela you are going to be our president in this prison.” That is how his name the Black President started. And the actual corner of this large cell where they put Fela is called Kalakuta.

You were also arrested. So what happened then?

We fifty-two were in the cells for a week and the torture and beatings in prison were too much. As I’m talking to you now I have weak teeth. Hitting me with gun, kicking me with boot, calling me a Ghanaian. Fela’s mother bailed Fela, and Beko [his brother] bailed Fela’s girlfriend, but as a Ghanaian I didn’t have anyone to bail me. However, later on one of the gatemen of the Shrine told the court clerk that that man you want to take to Ikoyi Prison is my in-law. So he bailed me too and we all started going to Court Two at Bode Thomas in Surulere for four months. Then they changed the judge and took me, Fela, and the others to another court in Apapa.

I made the mistake of telling the court that my father was a Ghanaian policeman, thinking I would be let free as a policeman’s son. Not knowing it was worsening things as the CID was saying I had three charges against me. That I was a Ghanaian who was bringing Ghanaian girls to Fela, that I had originally come into the country illegally, and that I had a false Nigerian passport. But it wasn’t true, as I had first come to Ghana on a band group-passport. Fortunately the two CID men who went to Ghana to investigate about me at police headquarters in Accra couldn’t get documented evidence on my father, as he had retired as a pensioner and couldn’t be located. So I was saved, as during the fourth month of the case, when the court was charged, the new judge couldn’t find my file. “Feelings Lawyer” [Wole Kuboye—one of Fela’s lawyers] said as there is no evidence that this man is a Ghanaian, he’s a Nigerian.

So I was discharged and acquitted, and when I jumped and shouted the judge said, “contempt of court.” So “People’s Lawyer” (another of Fela’s lawyers) told me to keep quiet while the judge read the acquittal verdict again. When I got outside Fela and the others were waiting and I shouted “Fela, Fela I’m free” and did somersaults and rolled on the ground. Fela said: “Yes, you are the first to win and now all of us are going to win our cases.”

What happened after your release?

I went on tour with Fela [then still out on bail] to Ilorin University in Kwara State and the police came and found Indian hemp in one of the saxophones as we were coming home. Then when we got back the police started looking for Fela, still in connection with the two girls. The band also went to Cameroons around this time and was also chased there by the Nigerian police.

Were you arrested during the second attack on his house that year in November 1974?

I had gone to the Ghana High Commission that day to a friend working there who normally gives us Ghanaian kenkey [fermented corn dough] and I was teargassed near the Shrine [by then the Empire Hotel] near Fela’s house [by then called Kalakuta]. I dropped the kenkey but wasn’t arrested. The police, however, did arrest two other Ghanaians—the conga player Nicholas Addo and my junior brother who was driving Fela’s mother’s car, called Aryee. After that Fela started dodging in hotels and so we were not playing for some time as Fela was being charged again with abducting girls.

We musicians were feeling hungry. I didn’t want to leave him as I loved him and his music but in early 1975 I joined a new juju-music group called the Juju Rock Stars and became a session musician at the EMI studio in Apapa. After that I joined Sonny Okosun’s band and featured in his Papa’s Land album. Then I was recruited to the University of Lagos cultural group by Igo Chico [a former saxophone player of Fela’s] and we played at the 1977 FESTAC black arts festival. I then met the university musicologist Joy Nwosu and worked with the Lagos University Cultural Centre Performing arts group until I recently retired.

What is Afrobeat?