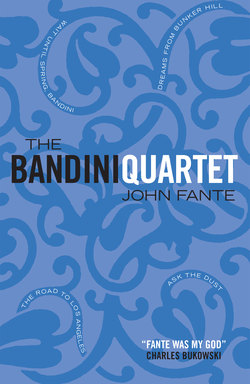

Читать книгу The Bandini Quartet - John Fante - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Five

Arturo Bandini was pretty sure that he wouldn’t go to hell when he died. The way to hell was the committing of mortal sin. He had committed many, he believed, but the confessional had saved him. He always got to confession on time – that is, before he died. And he knocked on wood whenever he thought of it – he always would get there on time – before he died. So Arturo was pretty sure he wouldn’t go to hell when he died. For two reasons. The confessional, and the fact that he was a fast runner.

But purgatory, that midway place between hell and heaven, disturbed him. In explicit terms the catechism stated the requirements for heaven: a soul had to be absolutely clean, without the slightest blemish of sin. If the soul at death was not clean enough for heaven, and not befouled enough for hell, there remained that middle region, that purgatory where the soul burned and burned until it was purged of its blemishes.

In purgatory there was one consolation: soon or late you were a cinch for heaven. But when Arturo realized that his stay in purgatory might be seventy million trillion billion years, burning and burning and burning, there was little consolation in ultimate heaven. After all, a hundred years was a long time. And a hundred and fifty million years was incredible.

No: Arturo was sure he would never go straight to heaven. Much as he dreaded the prospect, he knew that he was in for a long session in purgatory. But wasn’t there something a man could do to lessen the purgatory ordeal of fire? In his catechism he found the answer to this problem.

The way to shorten the awful period in purgatory, the catechism stated, was by good works, by prayer, by fasting and abstinence, and by piling up indulgences. Good works were out, as far as he was concerned. He had never visited the sick, because he knew no such people. He had never clothed the naked because he had never seen any naked people. He had never buried the dead because they had undertakers for that. He had never given alms to the poor because he had none to give; besides, ‘alms’ always sounded to him like a loaf of bread, and where could he get loaves of bread? He had never harbored the injured because – well, he didn’t know – it sounded like something people did on seacoast towns, going out and rescuing sailors injured in shipwrecks. He had never instructed the ignorant because after all, he was ignorant himself, otherwise he wouldn’t be forced to go to this lousy school. He had never enlightened the darkness because that was a tough one he never did understand. He had never comforted the afflicted because it sounded dangerous and he knew none of them anyway: most cases of measles and smallpox had quarantine signs on the doors.

As for the Ten Commandments he broke practically all of them, and yet he was sure that not all of these infringements were mortal sins. Sometimes he carried a rabbit’s foot, which was superstition, and therefore a sin against the First Commandment. But was it a mortal sin? That always bothered him. A mortal sin was a serious offense. A venial sin was a slight offense. Sometimes, playing baseball, he crossed bats with a fellow player: this was supposed to be a sure way to get a two-base hit. And yet he knew it was superstition. Was it a sin? And was it a mortal sin or a venial sin? One Sunday he had deliberately missed mass to listen to the broadcast of the world series, and particularly to hear of his god, Jimmy Foxx of the Athletics. Walking home after the game it suddenly occurred to him that he had broken the First Commandment: thou shalt not have strange gods before me. Well, he had committed a mortal sin in missing Mass, but was it another mortal sin to prefer Jimmy Foxx to God Almighty during the world series? He had gone to confession, and there the matter grew more complicated. Father Andrew had said, ‘If you think it’s a mortal sin, my son, then it is a mortal sin.’ Well, heck. At first he had thought it was only a venial sin, but he had to admit that, after considering the offense for three days before confession, it had indeed become a mortal sin.

The Second Commandment. It was no use even thinking about that, for Arturo said ‘God damn it’ on an average of four times a day. Nor was that counting the variations: God damn this and God damn that. And so, going to confession each week, he was forced to make wide generalizations after a futile examination of his conscience for accuracy. The best he could do was confess to the priest, ‘I took the name of the Lord in vain about sixty-eight or seventy times.’ Sixty-eight mortal sins in one week, from the Second Commandment alone. Wow! Sometimes, kneeling in the cold church awaiting confessional, he listened in alarm to the beat of his heart, wondering if it would stop and he drop dead before he got those things off his chest. It exasperated him, that wild beating of his heart. It compelled him not to run but often to walk, and very slowly, to confessional, lest he overdo the organ and drop in the street.

‘Honor thy father and thy mother.’ Of course he honored his father and his mother! Of course. But there was a catch in it: the catechism went on to say that any disobedience of thy father and thy mother was dishonor. Once more he was out of luck. For though he did indeed honor his mother and father, he was rarely obedient. Venial sins? Mortal sins? The classifications pestered him. The number of sins against that commandment exhausted him; he would count them to the hundreds as he examined his days hour by hour. Finally he came to the conclusion that they were only venial sins, not serious enough to merit hell. Even so, he was very careful not to analyze this conclusion too deeply.

He had never killed a man, and for a long time he was sure that he would never sin against the Fifth Commandment. But one day the class in catechism took up the study of the Fifth Commandment, and he discovered to his disgust that it was practically impossible to avoid sins against it. Killing a man was not the only thing: the by-products of the commandment included cruelty, injury, fighting, and all forms of viciousness to man, bird, beast, and insect alike.

Goodnight, what was the use? He enjoyed killing bluebottle flies. He got a big kick out of killing muskrats, and birds. He loved to fight. He hated those chickens. He had had a lot of dogs in his life, and he had been severe and often harsh with them. And what of the prairie dogs he had killed, the pigeons, the pheasants, the jackrabbits? Well, the only thing to do was to make the best of it. Worse, it was a sin to even think of killing or injuring a human being. That sealed his doom. No matter how he tried, he could not resist expressing the wish of violent death against some people: like Sister Mary Corta, and Craik the grocer, and the freshmen at the university, who beat the kids off with clubs and forbade them to sneak into the big games at the stadium. He realized that, if he wasn’t actually a murderer, he was the equivalent in the eyes of God.

One sin against that Fifth Commandment that always seethed in his conscience was an incident the summer before, when he and Paulie Hood, another Catholic boy, had captured a rat alive and crucified it to a small cross with tacks, and mounted it on an anthill. It was a ghastly and horrible thing that he never forgot. But the awful part of it was, they had done this evil thing on Good Friday, and right after saying the Stations of the Cross! He had confessed that sin shamefully, weeping as he told it, with true contrition, but he knew it had piled up many years in purgatory, and it was almost six months before he even dared kill another rat.

Thou shalt not commit adultery; thou shalt not think about Rosa Pinelli, Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, and Clara Bow. Oh gosh, oh Rosa, oh the sins, the sins, the sins. It began when he was four, no sin then because he was ignorant. It began when he sat in a hammock one day when he was four, rocking back and forth, and the next day he came back to the hammock between the plum tree and the apple tree in the back yard, rocking back and forth.

What did he know about adultery, evil thoughts, evil actions? Nothing. It was fun in the hammock. Then he learned to read, and the first of many things he read were the Commandments. When he was eight he made his first confession, and when he was nine he had to take the Commandments apart and find out what they meant.

Adultery. They didn’t talk about it in the fourth grade catechism class. Sister Mary Anna skipped it and spent most of the time talking about Honor thy Father and Mother and Thou Shalt Not Steal. And so it was, for vague reasons he never could understand, that to him adultery always has had something to do with bank robbery. From his eighth year to his tenth, examining his conscience before confession, he would pass over ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’ because he had never robbed a bank.

The man who told him about adultery wasn’t Father Andrew, and it wasn’t one of the nuns, but Art Montgomery at the Standard Station on the corner of Arapahoe and Twelfth. From that day on his loins were a thousand angry hornets buzzing in a nest. The nuns never talked about adultery. They only talked about evil thoughts, evil words, evil actions. That catechism! Every secret of his heart, every sly delight in his mind was already known to that catechism. He could not beat it, no matter how cautiously he tiptoed through the pinpoints of its code. He couldn’t go to the movies anymore because he only went to the movies to see the shapes of his heroines. He liked ‘love’ pictures. He liked following girls up the stairs. He liked girls’ arms, legs, hands, feet, their shoes and stockings and dresses, their smell and their presence. After his twelfth year the only things in life that mattered were baseball and girls, only he called them women. He liked the sound of the word. Women, women, women. He said it over and over because it was a secret sensation. Even at Mass, when there were fifty or a hundred of them around him, he reveled in the secrecy of his delights.

And it was all a sin – the whole thing had the sticky sensation of evil. Even the sound of some words was a sin. Ripple. Supple. Nipple. All sins. Carnal. The flesh. Scarlet. Lips. All sins. When he said the Hail Mary. Hail Mary full of grace, the Lord is with thee and blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb. The word shook him like thunder. Fruit of thy womb. Another sin was born.

Every week he staggered into the church of a Saturday afternoon, weighted down by the sins of adultery. Fear drove him there, fear that he would die and then live on forever in eternal torture. He did not dare lie to his confessor. Fear tore his sins out by the roots. He would confess it all fast, gushing with his uncleanliness, trembling to be pure. I committed a bad action I mean two bad actions and I thought about a girl’s legs and about touching her in a bad place and I went to the show and thought bad things and I was walking along and a girl was getting out of a car and it was bad and I listened to a bad joke and laughed and a bunch of us kids were watching a couple of dogs and I said something bad, it was my fault, they didn’t say anything, I did, I did it all, I made them laugh with a bad idea and I tore a picture out of a magazine and she was naked and I knew it was bad but did it anyway. I thought a bad thing about Sister Mary Agnes; it was bad and I kept on thinking. I also thought bad things about some girls who were laying on the grass and one of them had her dress up high and I kept on looking and knowing it was bad. But I’m sorry. It was my fault, all my fault, and I’m sorry, sorry.

He would leave the confessional, and say his penance, his teeth gritted, his fist tightened, his neck rigid, vowing with body and soul to be clean forevermore. A sweetness would at last pervade him, a soothing lull him, a breeze cool him, a loveliness caress him. He would walk out of the church in a dream, and in a dream he would walk, and if no one was looking he’d kiss a tree, eat a blade of grass, blow kisses at the sky, touch the cold stones of the church wall with fingers of magic, the peace in his heart like nothing save a chocolate malted, a three-base hit, a shining window to be broken, the hypnosis of that moment that comes before sleep.

No, he wouldn’t go to hell when he died. He was a fast runner, always getting to confession on time. But purgatory awaited him. Not for him the direct, pure route to eternal bliss. He would get there the hard way, by detour. That was one reason why Arturo was an altar boy. Some piety on this earth was bound to lessen the purgatory period.

He was an altar boy for two other reasons. In the first place, despite his ceaseless howls of protests, his mother insisted on it. In the second place, every Christmas season the girls in the Holy Name Society feted the altar boys with a banquet.

Rosa, I love you.

She was in the auditorium with the Holy Name Girls, decorating the tree for the altar boy banquet. He watched from the door, feasting his eyes upon the triumph of her tiptoed loveliness. Rosa: tinfoil and chocolate bars, the smell of a new football, goalposts with bunting, a home run with the bases full. I am an Italian too, Rosa. Look, and my eyes are like yours. Rosa, I love you.

Sister Mary Ethelbert passed.

‘Come, come, Arturo. Don’t dawdle there.’

She was in charge of the altar boys. He followed her black flowing robes to the ‘little auditorium’ where some seventy boys who comprised the male student body awaited her. She mounted the rostrum and clapped her hands for silence.

‘All right boys, do take your places.’

They lined up, thirty-five couples. The short boys were in front, the tall boys in the rear. Arturo’s partner was Wally O’Brien, the kid who sold the Denver Posts in front of the First National Bank. They were twenty-fifth from the front, the tenth from the rear. Arturo detested this fact. For eight years he and Wally had been partners, ever since kindergarten. Each year found them moved back farther, and yet they had never made it, never grown tall enough to make it back to the last three rows where the big guys stood, where the wisecracks came from. Here it was, their last year in this lousy school, and they were still stymied around a bunch of sixth- and seventh-grade punks. They concealed their humiliation by an exceedingly tough and blasphemous exterior, shocking the sixth-grade punks into a grudging and awful respect for their brutal sophistication.

But Wally O’Brien was lucky. He didn’t have any kid brothers in the line to bother him. Each year, with increasing alarm, Arturo had watched his brothers August and Federico moving toward him from the front rows. Federico was now tenth from the front. Arturo was relieved to know that this youngest of his brothers would never pass him in the line-up. For next June, thank God, Arturo graduated, to be through forever as an altar boy.

But the real menace was the blond head in front of him, his brother August. Already August suspected his impending triumph. Whenever the line was called to order he seemed to measure off Arturo’s height with a contemptuous sneer. For indeed, August was the taller by an eighth of an inch, but Arturo, usually slouched over, always managed to straighten himself enough to pass Sister Mary Ethelbert’s supervision. It was an exhausting process. He had to crane his neck and walk on the balls of his feet, his heels a half inch off the floor. Meanwhile he kept August in complete submission by administering smashing kicks with his knee whenever Sister Mary Ethelbert wasn’t looking.

They did not wear vestments, for this was only practice. Sister Mary Ethelbert led them out of the little auditorium and down the hall, past the big auditorium, where Arturo caught a glance of Rosa sprinkling tinsel on the Christmas tree. He kicked August and sighed.

Rosa, me and you: a couple of Italians.

They marched down three flights of stairs and across the yard to the front doors of the church. The holy water fonts were frozen hard. In unison, they genuflected; Wally O’Brien’s finger spearing the boys in front of him. For two hours they practiced, mumbling Latin responses, genuflecting, marching in miltary piousness. Ad deum qui loctificat, juventutem meum.

At five o’clock, bored and exhausted, they were finished. Sister Mary Ethelbert lined them up for final inspection. Arturo’s toes ached from bearing his full weight. In weariness he rested himself on his heels. It was a moment of carelessness for which he paid dearly. Sister Mary Ethelbert’s keen eye just then observed a bend in the line, beginning and ending at the top of Arturo Bandini’s head. He could read her thoughts, his weary toes rising in vain to the effort. Too late, too late. At her suggestion he and August changed places.

His new partner was a kid named Wilkins, fourth-grader who wore celluloid glasses and picked his nose. Behind him, triumphantly sanctified, stood August, his lips sneering implacably, no word coming from him. Wally O’Brien looked at his erstwhile partner in crestfallen sadness, for Wally too had been humiliated by the intrusion of this upstart sixth-grader. It was the end for Arturo. Out of the corner of his mouth he whispered to August.

‘You dirty –’ he said. ‘Wait’ll I get you outside.’

Arturo was waiting after practice. They met at the corner. August walked fast, as if he hadn’t seen his brother. Arturo quickened his pace.

‘What’s your hurry, Tall Man?’

‘I’m not hurrying, Shorty.’

‘Yes you are, Tall Man. And how would you like some snow rubbed in your face?’

‘I wouldn’t like it. And you leave me alone – Shorty.’

‘I’m not bothering you, Tall Man. I just want to walk home with you.’

‘Don’t you try anything now.’

‘I wouldn’t lay a hand on you, Tall Man. What makes you think I would?’

They approached the alley between the Methodist church and the Colorado Hotel. Once beyond that alley, August was safe in the view of the loungers at the hotel window. He sprang forward to run, but Arturo’s fist seized his sweater.

‘What’s the hurry, Tall Man?’

‘If you touch me, I’ll call a cop.’

‘Oh, I wouldn’t do that.’

A coupe passed, moving slowly. Arturo followed his brother’s sudden open-mouthed stare at the occupants, a man and a woman. The woman was driving, and the man had his arm at her back.

‘Look!’

But Arturo had seen. He felt like laughing. It was such a strange thing. Effie Hildegarde drove the car, and the man was Svevo Bandini.

The boys examined one another’s faces. So that was why Mamma had asked all those questions about Effie Hildegarde! If Effie Hildegarde was good looking. If Effie Hildegarde was a ‘bad’ woman.

Arturo’s mouth softened to a laugh. The situation pleased him. That father of his! That Svevo Bandini! Oh boy – and Effie Hildegarde was a swell-looking dame too!

‘Did they see us?’

Arturo grinned. ‘No.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘He had his arm around her, didn’t he?’

August frowned.

‘That’s bad. That’s going out with another woman. The Ninth Commandment.’

They turned into the alley. It was a short cut. Darkness came fast. Water puddles at their feet were frozen in the growing darkness. They walked along, Arturo smiling. August was bitter.

‘It’s a sin. Mamma’s a swell mother. It’s a sin.’

‘Shut up.’

They turned from the alley on Twelfth Street. The Christmas shopping crowd in the business district separated them now and then, but they stayed together, waiting as one another picked his way through the crowd. The street lamps went on.

‘Poor Mamma. She’s better than that Effie Hildegarde.’

‘Shut up.’

‘It’s a sin.’

‘What do you know about it? Shut up.’

‘Just because Mamma hasn’t got good clothes . . .’

‘Shut up, August.’

‘It’s a mortal sin.’

‘You’re dumb. You’re too little. You don’t know anything.’

‘I know a sin. Mamma wouldn’t do that.’

The way his father’s arm rested on her shoulder. He had seen her many times. She had charge of the girls’ activities at the Fourth of July celebration in the Courthouse Park. He had seen her standing on the courthouse steps the summer before, beckoning with her arms, calling the girls together for the big parade. He remembered her teeth, her pretty teeth, her red mouth, her fine plump body. He had left his friends to stand in the shadows and watch as she talked to the girls. Effie Hildegarde. Oh boy, his father was a wonder!

And he was like his father. A day would come when he and Rosa Pinelli would be doing it too. Rosa, let’s get into the car and drive out in the country, Rosa. Me and you, out in the country, Rosa. You drive the car and we’ll kiss, but you drive, Rosa.

‘I bet the whole town knows it,’ August said.

‘Why shouldn’t they? You’re like everybody else. Just because Papa’s poor, just because he’s an Italian.’

‘It’s a sin,’ he said, kicking viciously at frozen chunks of snow. ‘I don’t care what he is – or how poor, either. It’s a sin.’

‘You’re dumb. A saphead. You don’t savvy anything.’

August did not answer him. They took the short path over the trestle bridge that spanned the creek. They walked in single file, heads down, careful of the limitations of the deep path through the snow. They took the trestle bridge on tiptoe, from railroad tie to tie, the frozen creek thirty feet below them. The quiet evening spoke to them, whispering of a man riding in a car somewhere in the same twilight, a woman not his own riding with him. They descended the crest of the railroad line and followed a faint trail which they themselves had made all that winter in the comings and goings to and from school, through the Alzi pasture, with great sweeps of white on either side of the path, untouched for months, deep and glittering in the evening’s birth. Home was a quarter of a mile away, only a block beyond the fences of the Alzi pasture. Here in this great pasture they had spent a great part of their lives. It stretched from the backyards of the very last row of houses in the town, weary frozen cottonwoods strangled in the death pose of long winters on one side, and a creek that no longer laughed on the other. Beneath that snow was white sand once very hot and excellent after swimming in the creek. Each tree held memories. Each fence post measured a dream, enclosing it for fulfillment with each new spring. Beyond that pile of stones, between those two tall cottonwoods, was the graveyard of their dogs and Suzie, a cat who had hated the dogs but lay now beside them. Prince, killed by an automobile; Jerry, who ate the poison meat; Pancho the fighter, who crawled off and died after his last fight. Here they had killed snakes, shot birds, speared frogs, scalped Indians, robbed banks, completed wars, reveled in peace. But in that twilight their father rode with Effie Hildegarde, and the silent white sweep of the pasture land was only a place for walking on a strange road to home.

‘I’m going to tell her,’ August said.

Arturo was ahead of him, three paces away. He turned around quickly. ‘You keep still,’ he said. ‘Mamma’s got enough trouble.’

‘I’ll tell her. She’ll fix him.’

‘You shut up about this.’

‘It’s against the Ninth Commandment. Mamma’s our mother, and I’m going to tell.’

Arturo spread his legs and blocked the path. August tried to step around him, the snow two feet deep on either side of the path. His head was down, his face set with disgust and pain. Arturo took both lapels of his mackinaw and held him.

‘You keep still about this.’

August shook himself loose.

‘Why should I? He’s our father, ain’t he? Why does he have to do that?’

‘Do you want Mamma to get sick?’

‘Then what did he do it for?’

‘Shut up! Answer my question. Do you want Mamma to be sick? She will if she hears about it.’

‘She won’t get sick.’

‘I know she won’t – because you’re not telling.’

‘I am too.’

The back of his hand caught August across the eyes.

‘I said you’re not going to tell!’

August’s lips quivered like jelly.

‘I’m telling.’

Arturo’s fist tightened under his nose.

‘You see this? You get it if you tell.’

Why should August want to tell? What if his father was with another woman? What difference did it make, so long as his mother didn’t know? And besides, this wasn’t another woman: this was Effie Hildegarde, one of the richest women in town. Pretty good for his father; pretty swell. She wasn’t as good as his mother – no: but that didn’t have anything to do with it.

‘Go ahead and hit me. I’m telling.’

The hard fist pushed into August’s cheek. August turned his head away contemptuously. ‘Go ahead. Hit me. I’m telling.’

‘Promise not to tell or I’ll knock your face in.’

‘Pooh. Go ahead. I’m telling.’

He tilted his chin forward, ready for any blow. It infuriated Arturo. Why did August have to be such a damn fool? He didn’t want to hit him. Sometimes he really enjoyed knocking August around, but not now. He opened his fist and clapped his hands on his hips in exasperation.

‘But look, August,’ he argued. ‘Can’t you see that it won’t help to tell Mamma? Can’t you just see her crying? And right now, at Christmas time too. It’ll hurt her. It’ll hurt her like hell. You don’t want to hurt Mamma, you don’t want to hurt your own mother, do you? You mean to tell me you’d go up to your own mother and say something that would hurt the hell out of her? Ain’t that a sin, to do that?’

August’s cold eyes blinked their conviction. The vapors of his breath flooded Arturo’s face as he answered sharply. ‘But what about him? I suppose he isn’t committing a sin. A worse sin than any I commit.’

Arturo gritted his teeth. He pulled off his cap and threw it into the snow. He beseeched his brother with both fists. ‘God damn you! You’re not telling.’

‘I am too.’

With one blow he cut August down, a left to the side of his head. The boy staggered backward, lost his balance in the snow, and floundered on his back. Arturo was on him, the two buried in the fluffy snow beneath the hardened crust. His hands encircled August’s throat. He squeezed hard.

‘You gonna tell?’

The cold eyes were the same.

He lay motionless. Arturo had never known him that way before. What should he do? Hit him? Without relaxing his grip on August’s neck he looked off toward the trees beneath which lay his dead dogs. He bit his lip and sought vainly within himself the anger that would make him strike.

Weakly he said, ‘Please, August. Don’t tell.’

‘I’m telling.’

So he swung. It seemed that the blood poured from his brother’s nose almost instantly. It horrified him. He sat straddling August, his knees pinning down August’s arms. He could not bear the sight of August’s face. Beneath the mask of blood and snow August smiled defiantly, the red stream filling his smile.

Arturo knelt beside him. He was crying, sobbing with his head on August’s chest, digging his hands into the snow and repeating: ‘Please August. Please! You can have anything I got. You can sleep on any side of the bed you want. You can have all my picture show money.’

August was silent, smiling.

Again he was furious. Again he struck, smashing his fist blindly into the cold eyes. Instantly he regretted it, crawling in the snow around the quiet, limp figure.

Defeated at last, he rose to his feet. He brushed the snow from his clothes, pulled his cap down and sucked his hands to warm them. Still August lay there, blood still pouring from his nose: August the triumphant, stretched out like one dead, yet bleeding, buried in the snow, his cold eyes sparkling their serene victory.

Arturo was too tired. He no longer cared.

‘Okay, August.’

Still August lay there.

‘Get up, August.’

Without accepting Arturo’s arm he crawled to his feet. He stood quietly in the snow, wiping his face with a handkerchief, fluffing the snow from his blond hair. It was five minutes before the bleeding stopped. They said nothing. August touched his swollen face gently. Arturo watched him.

‘You all right now?’

He did not answer as he stepped into the path and walked toward the row of houses. Arturo followed, shame silencing him: shame and hopelessness. In the moonlight he noticed that August limped. And yet it was not a limp so much as a caricature of one limping, like the pained embarrassed gait of the tenderfoot who had just finished his first ride on a horse. Arturo studied it closely. Where had he seen that before? It seemed so natural to August. Then he remembered: that was the way August used to walk out of the bedroom two years before, on those mornings after he had wet the bed.

‘August,’ he said. ‘If you tell Mamma, I’ll tell everybody that you pee the bed.’

He had not expected more than a sneer, but to his surprise August turned around and looked him squarely in the face. It was a look of incredulity, a taint of doubt crossing the once cold eyes. Instantly Arturo sprang to the kill, his senses excited by the impending victory.

‘Yes, sir!’ he shouted. ‘I’ll tell everybody. I’ll tell the whole world. I’ll tell every kid in the school. I’ll write notes to every kid in the school. I’ll tell everybody I see. I’ll tell it and tell it to the whole town. I’ll tell them August Bandini pees the bed. I’ll tell ’em!’

‘No!’ August choked. ‘No, Arturo!’

He shouted at the top of his voice.

‘Yes sir, all you people of Rocklin, Colorado! Listen to this: August Bandini pees the bed! He’s twelve years old and he pees the bed. Did you ever hear of anything like that? Yipee! Everybody listen!’

‘Please, Arturo! Don’t yell. I won’t tell. Honest I won’t, Arturo. I won’t say a word! Only don’t yell like that. I don’t pee the bed, Arturo. I used to, but I don’t now.’

‘Promise not to tell Mamma?’

August gulped as he crossed his heart and hoped to die.

‘Okay,’ Arturo said. ‘Okay.’

Arturo helped him to his feet and they walked home.