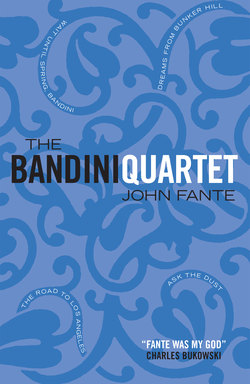

Читать книгу The Bandini Quartet - John Fante - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Six

No question about it: Papa’s absence had its advantages. If he were home the scrambled eggs for dinner would have had onions in them. If he were home they wouldn’t have been permitted to gouge out the white of the bread and eat only the crust. If he were home they wouldn’t have got so much sugar.

Even so, they missed him. Maria was so listless. All day she swished in carpet slippers, walking slowly. Sometimes they had to speak twice before she heard them. Afternoons she sat drinking tea, staring into the cup. She let the dishes go. One afternoon an incredible thing happened: a fly appeared. A fly! And in winter! They watched it soaring near the ceiling. It seemed to move with great difficulty, as though its wings were frozen. Federico climbed a chair and killed the fly with a rolled newspaper. It fell to the floor. They got down on their knees and examined it. Federico held it between his fingers. Maria knocked it from his hand. She ordered him to the sink, and to use soap and water. He refused. She seized him by the hair and dragged him to his feet.

‘You do what I tell you!’

They were astonished: Mamma had never touched them, had never said an unkind thing to them. Now she was listless again, deep in the ennui of a teacup. Federico washed and dried his hands. Then he did a surprising thing. Arturo and August were convinced that something was wrong, for Federico bent over and kissed his mother in the depths of her hair. She hardly noticed it. Absently she smiled. Federico slipped to his knees and put his head in her lap. Her fingers slid over the outlines of his nose and lips. But they knew that she hardly noticed Federico. Without a word she got up, and Federico looked after her in disappointment as she walked to the rocking chair by the window in the front room. There she remained, never moving, her elbow on the window sill, her chin in her hand as she watched the cold deserted street.

Strange times. The dishes remained unwashed. Sometimes they went to bed and the bed wasn’t made. It didn’t matter but they thought about it, of her in the front room by the window. Mornings she lay in bed and did not get up to see them off to school. They dressed in alarm, peeking at her from the bedroom door. She lay like one dead, the rosary in her hand. In the kitchen the dishes had been washed sometime during the night. They were surprised again, and disappointed: for they had awakened to expect a dirty kitchen. It made a difference. They enjoyed the change from a clean to a dirty kitchen. But there it was, clean again, their breakfast in the oven. They looked in before leaving for school. Only her lips moved.

Strange times.

Arturo and August walked to school.

‘Remember, August. Remember your promise.’

‘Huh. I don’t have to tell. She knows it already.’

‘No, she doesn’t.’

‘Then why does she act like that?’

‘Because she thinks it. But she doesn’t really know it.’

‘It’s the same.’

‘No it isn’t.’

Strange times. Christmas coming, the town full of Christmas trees, and the Santa Claus men from the Salvation Army ringing bells. Only three more shopping days before Christmas. They stood with famine-stricken eyes before shop windows. They sighed and walked on. They thought the same: it was going to be a lousy Christmas, and Arturo hated it, because he could forget he was poor if they didn’t remind him of it: every Christmas was the same, always unhappy, always wanting things he never thought about and having them denied. Always lying to the kids: telling them he was going to get things he could never possibly own. The rich kids had their day at Christmas. They could spread it on, and he had to believe them.

Wintertime, the time for standing around radiators in the cloak rooms, just standing there and telling lies. Ah, for spring! Ah, for the crack of the bat, the sting of a ball on soft palms! Wintertime, Christmas time, rich kid time: they had high-top boots and bright mufflers and fur-lined gloves. But it didn’t worry him very much. His time was the springtime. No high-top boots and fancy mufflers on the playing field! Can’t get to first base because you got a classy necktie. But he lied with the rest of them. What was he getting for Christmas? Oh, a new watch, a new suit, a lot of shirts and ties, a new bicycle, and a dozen Spalding Official National League Baseballs.

But what of Rosa?

I love you, Rosa. She had a way about her. She was poor too, a coal miner’s daughter, but they flocked around her and listened to her talk, and it didn’t matter, and he envied her and was proud of her, wondering if those who listened ever considered that he was an Italian too, like Rosa Pinelli.

Speak to me, Rosa. Look this way just once, over here Rosa, where I am watching.

He had to get her a Christmas present, and he walked the streets and peered into windows and bought her jewels and gowns. You’re welcome, Rosa. And here is a ring I bought you. Let me put it on your finger. There. Oh, it’s nothing, Rosa. I was walking along Pearl Street, and I came to Cherry’s Jewelry Shop, and I went in and bought it. Expensive? Naaaw. Three hundred, is all. I got plenty of money, Rosa. Haven’t you heard about my father? We’re rich. My father’s uncle in Italy. He left us everything. We come from fine people back there. We didn’t know about it, but come to find out, we were second cousins of the Duke of Abruzzi. Distantly related to the King of Italy. It doesn’t matter, though. I’ve always loved you, Rosa, and just because I come from royal blood never will make any difference.

Strange times. One night he got home earlier than usual. He found the house empty, the back door wide open. He called his mother but got no answer. Then he noticed that both stoves had gone out. He searched every room in the house. His mother’s coat and hat were in the bedroom. Then where could she be?

He walked into the back yard and called her.

‘Ma! Oh, Ma! Where are you?’

He returned to the house and built a fire in the front room. Where could she be without her hat and coat in this weather? God damn his father! He shook his fist at his father’s hat hanging in the kitchen. God damn you, why don’t you come home! Look what you’re doing to Mamma! Darkness came suddenly and he was frightened. Somewhere in that cold house he could smell his mother, in every room, but she was not there. He went to the back door and yelled again.

‘Ma! Oh, Ma! Where are you?’

The fire went out. There was no more coal or wood. He was glad. It gave him an excuse to leave the house and fetch more fuel. He seized a coal bucket and started down the path.

In the coal shed he found her, his mother, seated in the darkness in the corner, seated on a mortar board. He jumped when he saw her, it was so dark and her face so white, numb with cold, seated in her thin dress, staring at his face and not speaking, like a dead woman, his mother frozen in the corner. She sat away from the meager pile of coal in the part of the shed where Bandini kept his mason’s tools, his cement and sacks of lime. He rubbed his eyes to free them from the blinding light of snow, the coal bucket dropped at his side as he squinted and watched her form gradually assume clarity, his mother sitting on a mortar board in the darkness of the coal shed. Was she crazy? And what was that she held in her hand?

‘Mamma!’ he demanded. ‘What’re you doing in here?’

No answer, but her hand opened and he saw what it was: a trowel, a mason’s trowel, his father’s. The clamor and protest of his body and mind took hold of him. His mother in the darkness of the coal shed with his father’s trowel. It was an intrusion upon the intimacy of a scene that belonged to him alone. His mother had no right in this place. It was as though she had discovered him there, committing a boy-sin, that place, identically where he had sat those times; and she was there, angering him with his memories and he hated it, she there, holding his father’s trowel. What good did that do? Why did she have to go around reminding herself of him, fooling with his clothes, touching his chair? Oh, he had seen her plenty of times – looking at his empty place at the table; and now, here she was, holding his trowel in the coal shed, freezing to death and not caring, like a dead woman. In his anger he kicked the coal bucket and began to cry.

‘Mamma!’ he demanded. ‘What’re you doing! Why are you out here? You’ll die out here, Mamma! You’ll freeze!’

She arose and staggered toward the door with white hands stretched ahead of her, the face stamped with cold, the blood gone from it as she walked past him and into the semi-darkness of the evening. How long she had been there he did not know, possibly an hour, possibly more, but he knew she must be half dead with cold. She walked in a daze, staring here and there as if she had never known that place before.

He filled the coal bucket. The shed smelled tartly of lime and cement. Over one rafter hung a pair of Bandini’s overalls. He grabbed at them and ripped the overalls in two. It was all right to go around with Effie Hildegarde, he liked that all right, but why should his mother suffer so much, making him suffer? He hated his mother too; she was a fool, killing herself on purpose, not caring about the rest of them, him and August and Federico. They were all fools. The only person with any sense in the whole family was himself.

Maria was in bed when he got back to the house. Fully clothed she lay shivering beneath the covers. He looked at her and made grimaces of impatience. Well, it was her own fault: why did she want to go out like that? Yet he felt he should be sympathetic.

‘You all right, Mamma?’

‘Leave me alone,’ her trembling mouth said. ‘Just leave me alone, Arturo.’

‘Want the hot water bottle?’

She did not reply. Her eyes glanced at him out of their corners, quickly, in exasperation. It was a look he took for hatred, as if she wanted him out of her sight forever, as though he had something to do with the whole thing. He whistled in surprise: gosh, his mother was a strange woman; she was taking this too seriously.

He left the bedroom on tiptoe, not afraid of her but of what his presence might do to her. After August and Federico got home, she arose and cooked dinner: poached eggs, toast, fried potatoes, and an apple apiece. She did not touch the food herself. After dinner they found her at the same place, the front window, staring at the white street, her rosary clicking against the rocker.

Strange times. It was an evening of only living and breathing. They sat around the stove and waited for something to happen. Federico crawled to her chair and placed his hand on her knee. Still in prayer, she shook her head like one hypnotized. It was her way of telling Federico not to interrupt her, or to touch her, to leave her alone.

The next morning she was her old self, tender and smiling through breakfast. The eggs had been prepared ‘Mamma’s way,’ a special treat, the yolks filmed by the whites. And would you look at her! Hair combed tightly, her eyes big and bright. When Federico dumped his third spoonful of sugar into his coffee cup, she remonstrated with mock sternness.

‘Not that way, Federico! Let me show you.’

She emptied the cup into the sink.

‘If you want a sweet cup of coffee, I’ll give it to you.’ She placed the sugar bowl instead of the coffee cup on Federico’s saucer. The bowl was half full of sugar. She filled it the rest of the way with coffee. Even August laughed, though he had to admit there might be a sin in it – wastefulness.

Federico tasted it suspiciously.

‘Swell,’ he said. ‘Only there’s no room for the cream.’

She laughed, clutching her throat, and they were glad to see her happy, but she kept on laughing, pushing her chair away and bending over with laughter. It wasn’t that funny; it couldn’t be. They watched her miserably, her laughter not ending even though their blank faces stared at her. They saw her eyes fill with tears, her face swelling to purple. She got up, one hand over her mouth, and staggered to the sink. She drank a glass of water until it sputtered in her throat and she could not go on, and finally she staggered into the bedroom and lay on the bed, where she laughed.

Now she was quiet again.

They arose from the table and looked in at her on the bed. She was rigid, her eyes like buttons in a doll, a funnel of vapors pouring from her panting mouth and into the cold air.

‘You kids go to school,’ Arturo said. ‘I’m staying home.’

After they were gone, he went to the bedside.

‘Can I get you something, Ma?’

‘Go away, Arturo. Leave me alone.’

‘Should I call Dr Hastings?’

‘No. Leave me alone. Go away. Go to school. You’ll be late.’

‘Should I try to find Papa?’

‘Don’t you dare.’

Suddenly that seemed the right thing to do.

‘I’m going to,’ he said. ‘That’s just what I’m going to do.’ He hurried for his coat.

‘Arturo!’

She was out of bed like a cat. When he turned around in the clothes closet, one of his arms inside a sweater, he gasped to see her beside him so quickly. ‘Don’t you go to your father! You hear me – don’t you dare!’ She bent so close to his face that hot spittle from her lips sprinkled it. He backed away to the corner and turned his back, afraid of her, afraid to even look at her. With strength that amazed him she took him by the shoulder and swung him around.

‘You’ve seen him, haven’t you? He’s with that woman.’

‘What woman?’ He jerked himself away and fussed with his sweater. She tore his hands loose and took him by the shoulders, her finger-nails pinching the flesh.

‘Arturo, look at me! You saw him, didn’t you?’

‘No.’

But he smiled; not because he wished to torment her, but because he believed he had succeeded in the lie. Too quickly he smiled. Her mouth closed and her face softened in defeat. She smiled weakly, hating to know yet vaguely pleased that he had tried to shield her from the news.

‘I see,’ she said. ‘I see.’

‘You don’t see anything, you’re talking crazy.’

‘When did you see him, Arturo?’

‘I tell you I didn’t.’

She straightened herself and drew back her shoulders.

‘Go to school, Arturo. I’m all right here. I don’t need anybody.’

Even so, he remained home, wandering about the house, keeping the stoves fueled, now and then looking into her room, where she lay as always, her glazed eyes studying the ceiling, her beads rattling. She did not urge him to school again, and he felt he was of some use, that she was comforted with his presence. After a while he pulled a copy of Horror Crimes from his hiding place under the floor and sat reading in the kitchen, his feet on a block of wood in the oven.

Always he had wanted his mother to be pretty, to be beautiful. Now it obsessed him, the thought filtering beyond the pages of Horror Crimes and shaping itself into the misery of the woman lying on the bed. He put the magazine away and sat biting his lip. Sixteen years ago his mother had been beautiful, for he had seen her picture. Oh that picture! Many times, coming home from school and finding his mother weary and worried and not beautiful, he had gone to the trunk and taken it out – a picture of a large-eyed girl in a wide hat, smiling with so many small teeth, a beauty of a girl standing under the apple tree in Grandma Toscana’s backyard. Oh Mamma, to kiss you then! Oh Mamma, why did you change?

Suddenly he wanted to look at that picture again. He did the pulp and opened the door of the empty room off the kitchen, where his mother’s trunk was kept stored. He locked the door from the inside. Huh, and why did he do that? He unlocked it. The room was like an icebox. He crossed to the window where the trunk stood. Then he returned and locked the door again. Vaguely he felt he should not be doing this, yet why not: couldn’t he even look at a picture of his mother without a sense of evil degrading him? Well, suppose it wasn’t his mother, really: it used to be, so what was the difference?

Beneath layers of linen and curtains that his mother was saving until ‘we get a better house,’ beneath ribbons and baby clothes once worn by himself and his brothers, he found the picture. Ah, man! He held it up and stared at the wonder of that lovely face: here was the mother he had always dreamed about, this girl, no more than twenty, whose eyes he knew resembled his own. Not that weary woman in the other part of the house, she with the thin tortured face, the long bony hands. To have known her then, to have remembered everything from the beginning, to have felt the cradle of that beautiful womb, to have lived remembering from the beginning, and yet he remembered nothing of that time, and always she had been as she was now, weary and with that wistfulness of pain, the great eyes those of someone else, the mouth softer as if from much crying. He traced with his finger the line of her face, kissing it, sighing and murmuring of a past he had never known.

As he put the picture away, his eye fell upon something in one corner of the trunk. It was a tiny jewel box of purple velvet. He had never seen it before. Its presence surprised him, for he had gone through the trunk many times. The little purple box opened when he pressed the spring lock. Inside it, nestling in a silk couch was a black cameo on a gold chain. The dim writing on a card under the silk told him what it was. ‘For Maria, married one year today. Svevo.’

His mind worked fast as he shoved the little box into his pocket and locked the trunk. Rosa, Merry Christmas. A little gift. I bought it, Rosa. I’ve been saving up for it a long time. For you, Rosa. Merry Christmas.

He was waiting for Rosa next morning at eight o’clock, standing at the water fountain in the hall. It was the last day of classes before Christmas vacation. He knew Rosa always got to school early. Usually he barely made the last bell, running the final two blocks to school. He was sure the nuns who passed regarded him suspiciously, despite their kindly smiles and greetings for a Merry Christmas. In his right coat pocket he felt the snug importance of his gift for Rosa.

By eight fifteen the kids began to arrive: girls, of course, but no Rosa. He watched the electric clock on the wall. Eight thirty, and still no Rosa. He frowned with displeasure: a whole half hour spent in school, and for what? For nothing. Sister Celia, her glass eye brighter than the other, swooped downstairs from the convent quarters. Seeing him there on one foot, Arturo who was usually late, she glanced at the watch on her wrist.

‘Good heavens! Is my watch stopped?’

She checked with the electric clock on the wall.

‘Didn’t you go home last night, Arturo?’

‘Sure, Sister Celia.’

‘You mean you deliberately arrived a half hour early this morning?’

‘I came to study. Behind in my algebra.’

She smiled her doubt. ‘With Christmas vacation beginning tomorrow?’

‘That’s right.’

But he knew it didn’t make sense.

‘Merry Christmas, Arturo.’

‘Ditto, Sister Celia.’

Twenty to nine, and no Rosa. Everyone seemed to stare at him, even his brothers, who gaped as though he was in the wrong school, the wrong town.

‘Look who’s here!’

‘Beat it, punk.’ He bent over to drink some ice water.

At ten of nine she opened the big front door. There she was, red hat, camel’s hair coat, zipper overshoes, her face, her whole body lighted up with the cold flame of the winter morning. Nearer and nearer she came, her arms draped lovingly around a great bundle of books. She nodded this way and that to friends, her smile like a melody in that hall: Rosa, president of the Holy Name Girls, everybody’s sweetheart coming nearer and nearer in little galoshes that flapped with joy, as though they loved her too.

He tightened the grip around the jewel box. A sudden gusher of blood thundered through his throat. The vivacious sweep of her eyes centered for a fleeting moment upon his tortured ecstatic face, his mouth open, his eyes bulging as he swallowed down his excitement.

He was speechless.

‘Rosa . . . I . . . here’s . . .’

Her gaze went past him. The frown became a smile as a classmate rushed up and swept her away. They walked into the cloak room, chattering excitedly. His chest sank. Nuts. He bent over and gulped ice water. Nuts. He spat the water out, hating it, his whole mouth aching. Nuts.

He spent the morning writing notes to Rosa, and tearing them up. Sister Celia had the class read Van Dyke’s The Other Wise Man. He sat there bored, his mind attuned to the healthier writings found in the pulps.

But when it was Rosa’s turn to read he listened as she enunciated with a kind of reverence. Only then did the Van Dyke trash have significance. He knew it was a sin, but he had absolutely no respect for the story of the birth of the infant Jesus, the flight into Egypt, and the narrative of the child in the manger. But this line of thought was a sin.

During the noon hour, he stalked after her; but she was never alone, always with friends. Once she looked over the shoulders of a girl as a group of them stood in a circle and saw him, as if with a prescience of being followed. He gave up, then, ashamed, and pretended to swagger down the hall. The bell rang and afternoon class began. While Sister Celia talked mysteriously of the Virgin Birth, he wrote more notes to Rosa, tearing them up and writing others. Now he realized he was unequal to the task of presenting the gift to her in person. Someone else would have to do that. The note that satisfied him was:

Dear Rosa:

Here is a Merry Xmas

from

Guess Who

It hurt him when he realized that she would not accept the gift if she recognized the handwriting. With clumsy patience he rewrote it with his left hand, scrawling it in a wild, awkward script. But who would deliver the gift? He studied the faces of classmates around him. None of them, he realized, could possibly keep a secret. He solved the matter by raising two fingers. With the saccharine benevolence of the Christmas season, Sister Celia nodded her permission for him to leave the room. He tiptoed down the side aisle toward the cloak room.

He recognized Rosa’s coat at once, for he was familiar with it, having touched and smelled it on similar occasions. He slipped the note inside the box and dropped the box inside the coat pocket. He embraced the coat, inhaling the fragrance. In the side pocket he found a tiny pair of kid gloves. They were well worn, the little fingers showing holes.

Aw, jiminy: cute little holes. He kissed them tenderly. Dear little holes in the fingers. Sweet little holes. Don’t you cry, cute little holes, you just be brave and keep her fingers warm, her cunning little fingers.

He returned to the classroom, down the side aisle to his seat, his eyes as far away from Rosa as possible, for she must not know, or ever suspect him.

When the dismissal bell rang, he was the first out of the big front doors, running down the street. Tonight he would know if she cared at all, for tonight was the Holy Name banquet for the altar boys. Passing through town, he kept his eyes open for sight of his father, but his watchfulness was unrewarded. He knew he should have remained at school for altar boy practice, but that duty had become unbearable with his brother August behind him and the boy across from him, his partner, a miserable fourth-grade shrimp.

Reaching home, he was astonished to find a Christmas tree, a small spruce, standing in the corner by the window in the front room. Sipping tea in the kitchen, his mother was apathetic about it.

‘I don’t know who it was,’ she said. ‘A man in a truck.’

‘What kind of a man, Mamma?’

‘A man.’

‘What kind of a truck?’

‘Just a truck.’

‘What did it say on the truck?’

‘I don’t know. I didn’t pay any attention.’

He knew she was lying. He loathed her for this martyr-like acceptance of their plight. She should have thrown the tree back into the man’s face. Charity! What did they think his family was – poor? He suspected the Bledsoe family next door: Mrs Bledsoe, who wouldn’t let her Danny and Phillip play with that Bandini boy because he was (1) an Italian, (2) a Catholic, and (3) a bad boy leader of a gang of hoodlums who dumped garbage on her front porch every Hallowe’en. Well, hadn’t she sent Danny with a Thanksgiving basket last Thanksgiving, when they didn’t need it, and hadn’t Bandini ordered Danny to take it back?

‘Was it a Salvation Army truck?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Was the man wearing a soldier hat?’

‘I don’t remember.’

‘It was the Salvation Army, wasn’t it? I bet Mrs Bledsoe called them up.’

‘What if it was?’ Her voice came through her teeth. ‘I want your father to see that tree. I want him to look at it and see what he’s done to us. Even the neighbors know about it. Ah, shame, shame on him.’

‘To heck with the neighbors.’

He walked toward the tree with his fists doubled pugnaciously. ‘To heck with the neighbors.’ The tree was about his own height, five feet. He rushed into its prickly fullness and tore at the branches. They had a tender willowy strength, bending and cracking but not breaking. When he had disfigured it to his satisfaction, he threw it into the snow in the front yard. His mother made no protest, staring always into the teacup, her dark eyes brooding.

‘I hope the Bledsoes see it,’ he said. ‘That’ll teach them.’

‘God’ll punish him,’ Maria said. ‘He will pay for this.’

But he was thinking of Rosa, and of what he would wear to the altar boy banquet. He and August and his father always fought about that favorite gray tie, Bandini insisting it was too old for boys, and he and August answering it was too young for a man. Yet somehow it had always remained ‘Papa’s tie,’ for it had that good father-feeling about it, the front of it showing faint wine-spots and smelling vaguely of Toscanelli cigars. He loved that tie, and he always resented it if he had to wear it immediately after August, for then the mysterious quality of his father was somehow absent from it. He liked his father’s handkerchiefs too. They were so much bigger than his own, and they possessed a softness and a mellowness from being washed and ironed so many times by his mother, and in them he had a vague feeling of his mother and father at the same time. They were unlike the necktie, which was all father, and when he used one of his father’s handkerchiefs there came to him dimly a sense of his father and mother together, part of a picture, of a scheme of things.

For a long time he stood before the mirror in his room talking to Rosa, rehearsing his acknowledgment of her thanks. Now he was sure the gift would automatically betray his love. The way he had looked at her that morning, the way he had followed her during the noon hour – she would undoubtedly associate those preliminaries with the jewel. He was glad. He wanted his feelings in the open. He imagined her saying, I knew it was you all the time, Arturo. Standing at the mirror he answered, ‘Oh well, Rosa, you know how it is, a fellow likes to give his girl a Christmas present.’

When his brothers got home at four thirty he was already dressed. He did not own a complete suit, but Maria always kept his ‘new’ pants and ‘new’ coat neatly pressed. They did not match, but they came pretty close to it, the pants of blue serge and the coat an oxford gray.

The change into his ‘new’ clothes transformed him into a picture of frustration and misery as he sat in the rocking chair, his hands folded in his lap. The only thing he ever did when he got into his ‘new’ clothes, and he always did it badly, was simply to sit and wait out the period to the bitter end. Now he had four hours to wait before the banquet began, but there was some consolation in the fact that tonight, at least, he would not eat eggs.

When August and Federico let loose a barrage of questions about the broken Christmas tree in the front yard, his ‘new’ clothes seemed tighter than ever. The night was going to be warm and clear, so he pulled on one sweater over his gray coat instead of two and left, glad to be away from the gloom of home.

Walking down the street in that shadow-world of black and white he felt the serenity of impending victory: the smile of Rosa tonight, his gift around her neck as she waited on the altar boys in the auditorium, her smiles for him and for him alone.

Ah, what a night!

He talked to himself as he walked, breathing the thin mountain air, reeling in the glory of his possessions, Rosa my girl, Rosa for me and for nobody else. Only one thing disturbed him, and that vaguely: he was hungry, but the emptiness in his stomach was dissipated by the overflow of his joy. These altar boy banquets, and he had attended seven of them in his life, were supreme achievements in food. He could see it all before him, huge plates of fried chicken and turkey, hot buns, sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, and all the chocolate ice cream he could eat, and beyond it all, Rosa with a cameo around her neck, his gift, smiling as he gorged himself, serving him with bright black eyes and teeth so white they were good enough to eat.

What a night! He bent down and snatched at the white snow, letting it melt in his mouth, the cold liquid trickling down his throat. He did this many times, sucking the sweet snow and enjoying the cold effect in his throat.

The intestinal reaction to the cold liquid on his empty stomach was a faint purring somewhere in the middle of him and rising toward the cardiac area. He was crossing the trestle bridge, in the very middle of it, when everything before his eyes melted suddenly into blackness. His feet lost all sensory response. His breath came in frantic jerks. He found himself flat on his back. He had fallen over limply. Deep within his chest his heart hammered for movement. He clutched it with both hands, terror gripping him. He was dying: oh God, he was going to die! The very bridge seemed to shake with the violence of his heartbeat.

But five, ten, twenty seconds later he was still alive. The terror of that moment still burned in his heart. What had happened? Why had he fallen? He got up and hurried across the trestle bridge, shivering in fear. What had he done? It was his heart, he knew his heart had stopped beating and started again – but why?

Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa! The mysterious universe loomed around him, and he was alone on the railroad tracks, hurrying to the street where men and women walked, where it was not so lonely, and as he ran it came to him like piercing daggers that this was God’s warning, this was His way of letting him know that God knew his crime: he, the thief, filcher of his mother’s cameo, sinner against the decalogue. Thief, thief, outcast of God, hell’s child with a black mark across the book of his soul.

It might happen again. Now, five minutes from now. Ten minutes. Hail Mary full of grace I’m sorry. He no longer ran but walked now, briskly, almost running dreading over-excitation of his heart. Goodbye to Rosa and thoughts of love, goodbye and goodbye, and hello to sorrow and remorse.

Ah, the cleverness of God! Ah, how good the Lord was to him, giving him another chance, warning him yet not killing him.

Look! See how I walk. I breathe. I am alive. I am walking to God. My soul is black. God will clean my soul. He is good to me. My feet touch the ground, one two, one two. I’ll call Father Andrew. I’ll tell him everything.

He rang the bell on the confessional wall. Five minutes later Father Andrew appeared through the side door of the church. The tall, semi-bald priest raised his eyebrows in surprise to find but one soul in that Christmas-decorated church – and that soul a boy, his eyes tightly closed, his jaws gritted, his lips moving in prayer. The priest smiled, removed the toothpick from his mouth, genuflected, and walked toward the confessional. Arturo opened his eyes and saw him advancing like a thing of beautiful black, and there was comfort in his presence, and warmth in his black cassock.

‘What now, Arturo?’ he said in a whisper that was pleasant. He laid his hand on Arturo’s shoulder. It was like the touch of God. His agony broke beneath it. The vagueness of nascent peace stirred within depths, ten million miles within him.

‘I gotta go to confession, Father.’

‘Sure, Arturo.’

Father Andrew adjusted his sash and entered the confessional door. He followed, kneeling in the penitent’s booth, the wooden screen separating him from the priest. After the prescribed ritual, he said: ‘Yesterday, Father Andrew, I was going through my mother’s trunk, and I found a cameo with a gold chain, and I swiped it, Father. I put it in my pocket, and it didn’t belong to me, it belonged to my mother, my father gave it to her, and it musta been worth a lot of money, but I swiped it anyhow, and today I gave it to a girl in our school. I gave stolen property for a Christmas present.’

‘You say it was valuable?’ the priest asked.

‘It looked it,’ he answered.

‘How valuable, Arturo?’

‘It looked plenty valuable, Father. I’m awfully sorry, Father. I’ll never steal again as long as I live.’

‘Tell you what, Arturo,’ the priest said. ‘I’ll give you absolution if you’ll promise to go to your mother and tell her you stole the cameo. Tell her just as you’ve told me. If she prizes it, and wants it back, you’ve got to promise me you’ll get it from the girl, and return it to your mother. Now if you can’t do that, you’ve got to promise me you’ll buy your mother another one. Isn’t that fair, Arturo? I think God’ll agree that you’re getting a square deal.’

‘I’ll get it back. I’ll try.’

He bowed his head while the priest mumbled the Latin of absolution. That was all. Easy as pie. He left the confessional and knelt in the church, his hands pressed over his heart. It thumped serenely. He was saved. It was a swell world after all. For a long time he knelt, reveling in the sweetness of escape. They were pals, he and God, and God was a good sport. But he took no chances. For two hours, until the clock struck eight, he prayed every prayer he knew. Everything was coming out fine. The priest’s advice was a cinch. Tonight after the banquet he would tell his mother the truth – that he had stolen her cameo and given it to Rosa. She would protest at first. But not for long. He knew his mother, and how to get things out of her.

He crossed the schoolyard and climbed the stairs to the auditorium. In the hall the first person he saw was Rosa. She walked directly to him.

‘I want to talk to you,’ she said.

‘Sure, Rosa.’

He followed her downstairs, fearful that something awful was about to happen. At the bottom of the stairs she waited for him to open the door, her jaw set, her camel’s hair coat wrapped tightly around her.

‘I’m sure hungry,’ he said.

‘Are you?’ Her voice was cold, supercilious.

They stood on the stairs outside the door, at the edge of the concrete platform. She held out her hand.

‘Here,’ she said. ‘I don’t want this.’

It was the cameo.

‘I can’t accept stolen property,’ she said. ‘My mother says you probably stole this.’

‘I didn’t!’ he lied. ‘I did not!’

‘Take it,’ she said. ‘I don’t want it.’

He put it in his pocket. Without a word she turned to enter the building.

‘But Rosa!’

At the door she turned around and smiled sweetly.

‘You shouldn’t steal, Arturo.’

‘I didn’t steal!’ He sprang at her, dragged her out of the doorway and pushed her. She backed to the edge of the platform and toppled into the snow, after swaying and waving her arms in a futile effort to get her balance. As she landed her mouth opened wide and let out a scream.

‘I’m not a thief,’ he said looking down at her.

He jumped from the platform to the sidewalk and hurried away as fast as he could. At the corner he looked at the cameo for a moment, and then tossed it with all his might over the roof of the two-storey house bordering the street. Then he walked on again. To hell with the altar boy banquet. He wasn’t hungry anyway.