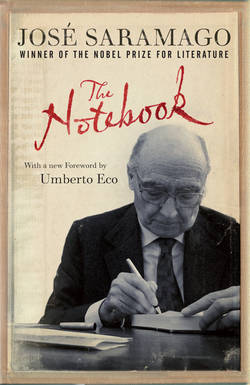

Читать книгу The Notebook - José Saramago - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

September 20: The Pulianas Cemetery

ОглавлениеOnce, perhaps seven or eight years ago, we were sought out, Pilar and I, by a man from León by the name of Emilio Silva, who was asking for support for an undertaking he was planning to embark upon: to find the remains of his grandfather, assassinated by the Francoists at the start of the civil war. He asked us for moral support, no more than that. His grandmother had expressed a wish that his grandfather’s bones should be recovered and given a dignified burial. Rather than just taking these words as the will of a bitter old woman, Emilio Silva took them as an order that it was his duty to fulfill, whatever might happen. This was the first step in a mass movement that quickly spread across all Spain: retrieving from ditches and ravines the tens of thousands of victims of fascist hatred that had been buried there, identifying them, and handing them over to their families. It was a massive task that did not enjoy universal support—and mention should be made of the continuous efforts of the Spanish political and social right to block it when it was already a thrilling reality, when the relics of those who had paid with their lives for fidelity to their ideas and to the legitimacy of the Republic were being raised from the dug-up and turned-over earth. Let me introduce here—in a symbolic bow to so many who have dedicated themselves to this work—the name of Ángel del Río, a brother-in-law of mine, who has given the best part of his time to it, including writing two books of research on the disappeared and those killed in reprisal.

It was inevitable that the rescuing of the remains of Federico García Lorca, buried like thousands of others in the Viznar ravine in the province of Granada, would quickly become a genuine national imperative. One of Spain’s greatest poets, the most universally known, there he is in that desert, that place we know almost as a certain fact is the ditch where the author of Romancero Gitano lies, along with three other men who had been shot—a primary school teacher called Dióscoro Galindo and two anarchists who had worked in the bull ring as banderilleros, Joaquín Arcollas Cabezas and Francisco Galadí Melgar. Strangely, however, García Lorca’s family has always opposed his exhumation. To a greater or lesser extent their arguments concern what we might call questions of social decorum, such as the unhealthy prurience of the media and the spectacle that would be made of the excavation of the skeletons, and these are undoubtedly respectable reasons, but, if I might be allowed to say this, today they are outweighed by the simplicity with which Dióscoro Galindo’s granddaughter replied when asked in a radio interview where she would take her grandfather’s remains if they were to be found: “To the Pulianas cemetery.” I should clarify that Pulianas, in the province of Granada, is the village where Dióscoro Galinda worked and where his family still lives. Pages in books are for turning over, pages in life are not.