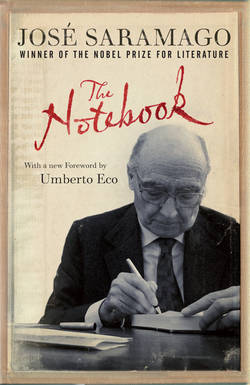

Читать книгу The Notebook - José Saramago - Страница 21

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

29 September: Clear as Water

ОглавлениеAs has always been the case, and as will always be the case, the central question concerning any kind of human social organization, and the one from and into which all others flow, is the question of power, and the theoretical and practical problem we are presented with is identifying who holds it, discovering how they attained it, checking what use they make of it, by what means and for what ends. If democracy really were what we continue (with real or feigned ingenuousness) to say it is, government of the people by the people for the people, any debate on the question of power would lose a lot of its meaning, since if power resides in the people it is the people who control it, and people controlling the power clearly would only do so for their own good and to secure their own happiness, compelled by what I call, with no pretension to conceptual rigor, the law of the preservation of life. Well, only a perverse spirit, Panglossian even to the point of cynicism, could dare to proclaim the happiness of a world that, on the contrary, nobody should expect us to accept as it is, just by virtue of its being, supposedly, the best of all possible worlds. This is the right and actual situation of the so-called democratic world, where if it is true that the people are governed, it is also true that they are not governed by or for themselves. It’s not a democracy that we live in, but a plutocracy, which has ceased to be local and close but has become instead at once universal and inaccessible.

Democratic power must by definition always be provisional and circumstantial; it depends on the stability of the vote, on the fluctuation of class interests or ideologies, and therefore can be understood as an organic barometer that registers variations in a society’s political will. But in the past, just as today—albeit to an increasingly great degree today—there have been numerous cases of apparently radical political changes that have resulted in radical changes in government but that were not followed by the radical economic, cultural, or social changes that the results of the vote had promised. Today, calling a government socialist, social democratic, conservative, or liberal is to ascribe power to it, that is, purport to identify something in it that is not really there but in some other place far out of reach—a place where you can see the filigree outlines of economic and financial power, a power that invariably eludes us when we try to get closer, that inevitably counterattacks if we whimsically wish to reduce or regulate its domain, subordinating it to the common good. In other, clearer words, then, what I’m saying is that people do not choose a government that will bring the market within their control; instead, the market in every way conditions governments to bring the people within its control. And if I talk about the market in this way it is only because today, and more with each day that passes, it is this that is the instrument par excellence of authentic, unitary, simple power, global economic and financial power, which is not democratic because the people never elected it, which is not democratic because the people do not govern it, and finally which is not democratic because it does not have the people’s happiness as its aim.

Our forefathers in their caves would say, “It is water.” We, being a little wiser, warn, “Yes, but it is contaminated.”