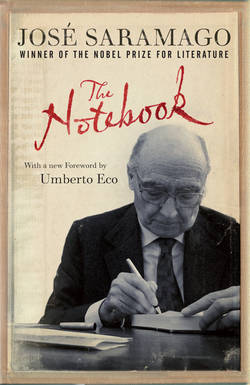

Читать книгу The Notebook - José Saramago - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

September 25: Nothing but Appearances

ОглавлениеI suppose that right at the very beginning, before we invented speech, which is, as we know, the supreme creator of uncertainties, we were not troubled by any serious doubts about who we were or about our personal and collective relationship with the place where we found ourselves. Of course, the world could only be what our eyes saw from one moment to the next and—which was equally significant information—what the remaining senses—hearing, touch, smell, taste—were able to perceive of it, too. In its earliest phase, the world was nothing but appearances and nothing but surface. Matter was rough or smooth, bitter or sweet, acidic or bland, noisy or silent, scented or odorless. All things were just what they seemed, simply because there was no reason for them to seem one thing and to be altogether another. In those most ancient of days it never occurred to us that matter was porous. Today, however, even though we know that from the smallest of viruses to the universe as a whole we are all no more than compositions of atoms, and that inside them, beyond the mass that is inherent to them and defines them, there is still enough space for emptiness (absolute density doesn’t exist; everything is permeable), we still—just like our ancestors in their caves—continue to learn about, identify, and recognize the world according to the way it repeatedly shows itself to us. I would imagine that the spirits of philosophy and of science must have appeared one day when someone suspected that although this appearance was an external image that could be captured by consciousness and used as a map of knowledge, it could also be a delusion of the senses. We all know the popular expression derived from this realization, though it is more often used to refer to the moral world than the physical one: “Appearances can mislead.” Or deceive, which comes to the same thing. There would be no shortage of examples had we but space for them.

This scribbler has always worried about what is hidden behind mere appearances, and I’m not talking now about atoms or sub-particles. What I am talking about are current, common, everyday questions about, for example, the political system that we call democracy, the system that Churchill described as “the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried.” He didn’t say it was good, only the least bad. One might say that we consider the government we can see to be more than sufficient, and I think this is an error of perception for which—without our noticing—we are paying the price every day. This is a subject to which I will return.