Читать книгу Vina: A Brooklyn Memoir - Joseph C. Polacco - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2. Julie is ‘De Man’

ОглавлениеSeems like Julie was always in my life. Julie (Giuli/Giulio) de Ramo is a rough-hewn bear of a man with a large heart. He’s in his mid-nineties, and has been a widower for almost twenty years. His Tootsie was loud, brash, very intelligent, and extremely supportive of her husband. She was Vina’s good and faithful friend, and she defended her to the extent that she would puncture the façade and posturing of my stepfather—only when he needed it, as all men do, at times. Understandably, Stepdad disliked her—intensely. Julie has been holding the fort without Tootsie, and for all but the last three years, Vina stepped into the breach, buttressing Julie’s forza (strength). I recall Julie’s dutiful 8:00 a.m. phone calls to Mom, on the heels of Florie’s. Hence, his chapter follows Florie’s. Mom’s sweet “Good morning” to Florie morphed into “Julie, don’t be ridiculous! You don’t remember what you told me yesterday?” The transition was from love to tough love.

Mom and Julie were an energetic comedy team—they argued about everything, especially food and food preparation. I was an avid listener to the mostly entertaining “play-by-play.” Even when they were on the phone, his voice at the other end was audible in most of Mom’s apartment. In the midst of recordings I made of my conversations with Mom, Julie called a few times, and I can actually make out what he is saying—this at a distance from the receiver of Mom’s now old-fashioned land line.

It seemed that Mom, the home team, usually came out on top of the “Julie-Vina Debates.” However, when Mom would pass the receiver to me, Julie never asked me to take sides; he always asked about my health, and that of my Nancy, kids, and grandkids.

The man can cook, however. He even makes his own salsiccia (sausage). Of course, Mom always said he used too much salt and oil. I can still see that butter “iceberg” floating in his clam sauce in the skillet. Julie still keeps an eye out for sales on 86th Street, though he can no longer count on Mom to pick up and drop off canned plum tomatoes, a quarter-pound of pine nuts, a tin of Medaglia d’Oro espresso grind, etcetera when she’s “in the neighborhood.” Beyond Mom’s eleven-block walk to the 86th Street emporia, she needed to schlep her two-wheeled cart another two long blocks to Julie’s apartment building. She’d say, “What does he think I am? I’m just an old broad, and it’s freezing (or hot) out there. If I fall on the ice, goodbye.” Then, in the same breath, “You gotta hand it to Julie, he’s doing all right for ninety-two, and he has all his marbles.”

Combining Florie’s grammar and vocabulary with Julie’s stories would be a Brooklynese epic poem, with alternate stanzas recited in the unique Brooklyn accents of each. Yes, I believe there are Jewish and Italian variations of the dialect. Of course Mom, the editor, would never agree with Julie’s details. So, one Easter Sunday, Nancy and I are at the apartment, and Julie is a guest. I mention zeppole and sfingi, which unleashes a spirited “discussion” about the difference—classic “Who’s on First?” material. Julie says: “Zeppole are fried dough with ricotta filling, like cannoli, and sometimes with a cherry or some other fruit on top. The sfingi have custard filling and powdered sugar.”

“Julie, what are you talking about?” says Mom. “The sfingi are stuffed with cannoli cream, and have orange zest and sugar on top.”

Then Julie offers, “I remember Alba’s Pastry Shop on 18th Avenue, every March and April…” Of course, by now, the battle royal is joined—except that Julie is in general retreat, and sfingi and zeppole changed uniforms several times during the campaign.

I should know the difference between zeppole and sfingi, ‘cause these are classic St. Joseph’s Day pastries. Mom would send me five bucks and a San Giuseppe card every March 19, Il Giorno del Mio Onomastico, which is my name saint’s day so I could buy the pastries—not much chance of doing so in Durham, North Carolina or Columbia, Missouri. A sabbatical in the Boston area did provide an outlet at the North End.

Julie’s stories keep me enrapt in his redundant biblical style: “So, I get to the door. I open it. I look up, and I hear a noise at the top of the stairs. So, I decided to go upstairs. I’m climbing, and, when I get up there, what do I see? Well, I looked, and…” (Tell me Julie, fercryinoutloud, the suspense is killing me!)

Among his several city jobs, Julie was a trolley conductor in his youth, when Brooklyn had trolleys. Indeed, the Brooklyn Dodgers got their name from the Trolley Dodgers. (Got trolleys, Los Angeles, huh?! And, while I’m at it, how many lakes are there in LA? Why did you not import water when you imported the Minneapolis Lakers? Too late now.) Julie’s trolley navigated all areas, from congested streets to tall-grass marshy fields—much of Bensonhurst is filled-in marshland; che peccato (what a pity!) “I gotta make this sharp turn, and cars know to stay outta my way, but this wise guy won’t move, and boom, body damage. He had some case against the city.” Linguistic sidebar: He had soooome case—drawn out, like “He had no case, what a chooch”—in “high Italian,” ciuccio, or jackass.

As a kid, I was just another guaglione, a ragamuffin kid of the ’hood. Guaglione sounds like why-OH, as in, “Why-OH, kay see-deech?” Guaglione, che si dice? or “Hey kiddo, whaddya say?” This guaglione recalls taking the West End line the three stops to Coney Island, and a few times seeing Julie working for NYC Transit. He seemed like an Italian Paul Bunyan. He made me feel okay for leaving Bensonhurst to go to college. He was great to my kids. I grew in his esteem, became a mensch, as a support for Mom through her difficult times with my stepfather especially at the end of his life, and then again later with her recurrent cancer.

During WWII, Julie was stationed in Natal, Brazil—the only person I know who did that—“I liked it; people were friendly, but a shot of whisky cost fifty cents.” Julie was very fortunate, and he owes his good luck to his mom. “I was born in a little village in Abruzzi, in 1920. My father was in the Italian army during WWI. My mother didn’t like what was happening after the war” under Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, and feared for her three sons. Julie’s mom encouraged her husband to emigrate to America. After returning to the old country a couple of times, Julie’s dad finally settled for good in Brooklyn, with his whole family—Mario, Eddie, kid bro' Giulio, and two sisters. But, Benito had a long arm, and Italians in Brooklyn had to evade it, not just the black hand of local warlords. In Bensonhurst, Julie attended a few meetings run by Mussolini’s representatives. The kids were given uniforms, sang patriotic songs, and were promised a free trip to Italy, and thence to Africa to take part in Il Duce’s glorious restoration of Imperial Rome. Julie didn’t buy into it, but “A good buddy of mine went over, and I never heard from him again.”

I don’t want to paint a picture of Brooklyn as an extension of the “old country” as embodied by Julie. He and Tootsie made an annual pilgrimage to the Grand Ole Opry. They loved country music. Julie’s jeans were held up with a handsome leather belt and cowboy buckle. Julie and Tootsie made friends with other fans from the Southland. South Brooklyn to Southland—what a country.

Watching Julie receive Mom’s vitriol—lovingly administered like castor oil—he seemed so mollified, and his retorts were equal parts gruff, tender, and ineffectual. He was Mom’s great sparring partner, and each got stronger from their encounters. I saw his strength when I arrived in Brooklyn on the eve of Mom’s scheduled lumpectomy. It appeared that she was being swallowed by New York’s bureaucratic medical morass—miscommunications and lost messages were about to scotch the surgery. She had to navigate that system, relying on public transportation to various treatment venues. While Mom never learned to drive, Julie’s eyesight now precluded it. So, Julie was no longer Mom’s escort, and his instructions over the phone were clear and commanding, telling me to take no guff from intermediaries, demand to speak with people in charge, and to force the issue, as a Brooklyn son should. She did have the surgery, endured seven consecutive weeks of daily radiation sessions on her own, and spent the next seven years “cancer-free.” Alas, the magic of seven had a time limit.

In mid-2015, I chatted with Julie on the phone. His eyesight problems were now keeping him mostly house-bound. I know Mom would have served as his guide-dog on many occasions. Working together in the kitchen? Well, friendship goes only so far.

I quote Julie verbatim: “When I’m on 86th Street, I say ‘Vina, where are you?’ She had an effect on people—they came to her. If she had a different husband, her house would be like Mary Napolitano’s— always full of people.”

That may have been the last time we chatted over the phone. A few months later, Julie entered a nursing home, and he passed at the very end of 2015. He lived ninety-five full years.

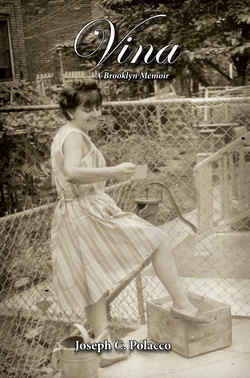

Photo courtesy Toni Caggiano

Julie, Vina and the Adams at a family gathering.

Front five participants, counterclockwise from left: Tootsie de Ramo, Vina, Georgette Adams, Julie de Ramo, Arthur Adams, 1998;

Good-looking lady, left background: Armida, Toni Caggiano’s sister.