Читать книгу Vina: A Brooklyn Memoir - Joseph C. Polacco - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6. Georgette, La Vucciria, and La Moda

ОглавлениеNo story about Georgette Adams is complete without including her never-married aunts, Mary and Rose, ninety-six, and one-hundred-one years old as I write this. “Spinster” is, yes, a pejorative, but if a pair of unmarried sisters deserves to wear the title as an honorific, it is Mary and Rose. They live together by their lonesome in a large wood-frame house, and their backyard is just “katty korner” from where Georgette’s backyard was. Georgette’s house used to be on 21st Avenue, two houses south of commercial 86th Street, but seemingly in a different, more rural world—rural by Bensonhurst standards. In the not-so-old days, sweet Georgette would call in on her aunts daily. While Mary was perfectly able to engage in the Olympic event of shopping on 86th Street, Georgette often shopped for the sisters, and ministered to them in other ways.

I need to digress about 86th Street, the “Casbah” so important in the life of Mom and of those she touched. The north side of the long block between Bay Parkway (22nd Avenue) and 23rd Avenue consists of open-air produce and schlock markets cheek by jowl, most of which have space inside for cash registers, dry goods, and more merchandise/produce. The owners have changed over the years, from Jewish and Italian in the fifties and sixties, to Koreans, Chinese, Egyptians, Arabs, Russians, et al. While Asians have conglomerated neighboring businesses into open-air “supermarkets,” at least one Italian family has done the same. Hence, La Vucciria encompasses at least three contiguous properties and on the inside, in addition to Italian favorites such as artichokes and broccoli di rapa (robbies), there is a functioning Russian deli counter, tended by white tunic-clad young Russian ladies. You vant smoked fish? You got it. Ochin xharascho! Molto bene! That’s Brooklyn. La Vucciria is aptly named. It means, loosely, “madhouse,” and is the title of Renato Guttuso’s famous painting of the “palermitano” market, which depicts a scene reminiscent of 86th Street. It’s life imitating art, imitating life. A large picture, a mural almost, of La Vucciria adorns the Bensonhurst namesake.

Now, fresh produce has always made 86th Street famous, even before fresh produce was cool and co-opted by the young hipsters by the Brooklyn Bridge and DUMBO. DUMBO? Well, almost Disneyesque, but it stands for “Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass.” The West End line goes over the Manhattan Bridge— flanked by the Brooklyn Bridge to the south and the Williamsburg Bridge to the north. Back in the day, you were more likely to find bodies by the bridge than the modern, more genteel tourist attractions like picnicking and kayaking.

On 86th Street in Bensonhurst, if you’re picking through produce when a bunch of new carciofi (artichokes) or string beans is dumped on the stand, you have to fight a gaggle of aggressive ladies (and a few brave, battle-hardened men) on the lookout for the prime specimens. And they also know about positioning, blocking out, and using elbows. Rose Seminara, the elder, when she was in her late eighties—early nineties, was right there. From Georgette: “Your mom was helping my Aunt Rose pick out string beans. They were picking them out one-by-one, not by the handful, because Mary would have a fit if Rose came home with spotted or rotten beans.” Now, this was a bitterly cold day, mind you, and Rose was putting bony, delicate, yet rapacious fingers on the choice specimens.

When the man came and dumped a new crate of string beans over the old ones, my aunt emptied the already full bag and proceeded to start over, and your mom said, “Enough! Rose, you got to be kidding!”

I heard this story from Mom as well as from Georgette, and I could just see Mom saying: “Abbastanza! Ma, quando, MAI?!” Roughly translated, “Enough! When will you be done, NEVER?!” Not even Mom could put her numb fingers through another string bean hunt. Now, if they were for her own table, probably a different story.

Rose, Mary, and Georgette are of the talented and accomplished Seminara clan—Sicilians who belie Hollywood stereotypes. Their numbers include dentists, lawyers and doctors. Aurora Seminara, PhD, was a student of 1998 Nobel Prize winner Ferid Murad. Stephanie Seminara is currently Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Earlier in her career she was able to master human genetics and genomics to identify a “puberty gene” which she called part of “the pilot light of puberty.” Georgette married Arthur Adams, of Canton, Ohio: “I met Art after he came out of the Navy (six years—during Vietnam). He went home for a while, and then came to the big city, New York. We met through a friend.”

To me, Arthur has thoroughly demonstrated how the environment can influence the “epigenome,” so that he is now a full-blown goombah. Talk about the confluence of the ’hood and rural mid-America: Arthur is now a conductor for the New York Transit Authority, and pilots the West End Express. (Currently the D, but we all know, and use, the real name.) As he barreled down 86th Street between the 20th Avenue and Bay Parkway (22nd Avenue) stations, he tooted his horn to his bride, who stood waving at him from her 21st Avenue back porch. Alas, no more. They had to sell a house that was sitting on a large footprint, on which will soon stand a five-story luxury condominium, with stores at ground level and subterranean parking. And so continues gentrification; enough of that.

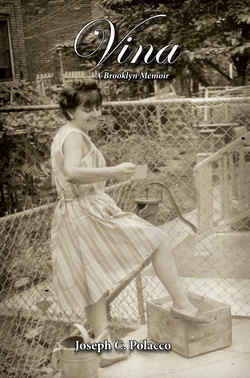

I should not get too maudlin or hand-wringing, ’cause in the very old days, Brooklyn was a collection of Dutch farming communities, and efforts to stem urbanization bore no fruit. Old Peter Stuyvesant, New York’s last Dutch governor (1664), probably did a few roll-overs in his grave over the Bensonhurst of my youth. However, this does not mean that today there are no urban gardens. Indeed, I cultivated tomatoes, Swiss chard (bietola, or scarola, depending on who you ask), and gogozelle (cucuzza, or goo-GOOTZ, in dialect; a long, sinuous light green squash) in the postage stamp of exposed soil behind our three rooms. A Sicilian immigrant, Mr. Spadaro, bought and renovated the house over the back fence. He commandeered neighbors’ terrain, and his backyard looked like a rural garden, complete with a grape trellis and fig trees he had to prune and wrap in tar paper to over-winter. He encouraged my “farming," and would often water my plants through the chain-link fence. I was the farmiol (farm-eye-OHL, as it sounded to me in dialect). Mrs. Spadaro shared some of her husband’s tomato preserves with us each year. It didn’t hurt that Mom was extremely good to her. The cover photo captures Mom chatting over the back fence with Lucia (Lucy) Spadaro about grandkids. I am thankful I did not become bipolar living in the linear gradient traced from 86th Street madness, through our store, and home to the Spadaro rural Sicilian plot.

So, Georgette and Arthur’s home was a parcel of the “rural residue” of Bensonhurst. Though their house was large, its footprint was less than half of their lot; so, they could grow tomatoes, basilicó (basil—bah-zilly-GO in dialect), peppers, etcetera. They even had a chicken—an escapee from a neighbor child’s Easter present. The chick crawled through the fence, and Arthur built a roost for her. Over the last few of her eleven years, she just nestled in with the curled-up dog on the back porch.

Georgette sings to my mother many mornings, and prays for her soul and the health of my daughter as well. Mom used to bring her aunts, “the sisters,” the Sunday editions of the Daily News and New York Post and then stay for morning coffee and breakfast, dropping by Georgette’s on the way home. I loved that Florie and Georgette got to know each other through their own mothers. I never knew those ladies, but I think that they were part of a vanguard of womanhood looking for expression and fulfillment beyond the familial.

Georgette is a smart cookie, but she is so good that she sometimes crumbles when she should hold fast, at least in my opinion. When I’m tempted to sound off on my professional accomplishments to Georgette and Arthur, I am chastened by the evidence of their strong intellects. For example, Georgette is a master of Sudoku, and Arthur, a master mechanic. Not that they brag—the evidence is all over the house, and Georgette and Arthur are heroes to their three children-in-law. The Italian lineage is now yet another ingredient in the protean Brooklyn minestrone, and their grandkids impart flavors of Haiti, Georgia (the ex-Soviet Republic), and other locales, and it’s all good, tasty, and sustaining. Mom was absolutely delirious over Georgette’s grandson Quinn.

Georgette also appreciated genius in others. Once, when sewing kitchen curtains,

Vina asked if she could do it for me. I thanked her and told her that I wanted to do it myself as a project. I was okay with straight seams, but when I needed to make the pleats for the hooks, I couldn’t get it right. Sooooo, I waited for Vina to come by, which she always did when on 86th Street, and she proceeded to teach me how to do the pleats—so easy when shown by a master. She supervised me while I did them on my machine, and left it to me to finish.

Georgette then needed to place trim on the kitchen window over the sink to match the curtains.

Well, after trying several times to get it right, I was ready to throw the whole thing out. Again Vina, without hesitation, came to my rescue. She took the curtain home, and next day delivered to me the finished curtain complete with the matching trim. They have been on my window ever since. I don’t change them, just wash them and put them back up. I love them. It’s funny how at the time something like that could seem so insignificant, but now when I look at them, they remind me of her. They remind me how very blessed I was to have Vina in my life.

Mom’s creations made it out of the neighborhood, to Manhattan’s Upper East Side. Follow the winding plot: Leonard Sillman, Broadway producer/show biz entrepreneur, had “discovered” my brother Michael when he was working on a Pietro D’Agostino & Sons demolition project. After hearing Michael sing and play guitar, he featured Bro' as one of his “New Faces of 1971” in the February 20 issue of Cue magazine, page 9:

MICHAEL POLACCO. I first saw this multifaceted talent on the corner of my street, where a building was being demolished. This young Italian-American was part of the demolition squad. Each day, when work finished at three, this steel-helmeted young man got into his 1956 T-bird and roared down Fifth Avenue. My curiosity got the best of me, and I asked him what he was all about. He worked in demolition during summers to make enough money to finish at Visual Arts, and he didn’t know whether to be a camera man, a movie director, or a performer. Then, one day he played the guitar and sang for me. I immediately recognized a potential star. Michael is a brilliant lyricist-composer, and he has warmth and charm which, when he performs, light up any room. He has that marvelous thing called communication. Michael has just finished his first record album, and is looking for the right distributor. His songs are of today, tomorrow, and sometimes yesteryear.

In the early seventies, Michael helped girlfriend Theo get a job as one of Leonard’s assistants. Theo wore some of Mom’s creations around the office—cape, shawl, scarf, etcetera—and they caught Leonard’s eye. When told they were designed and made by Vina, Michael's mom, Leonard realized he had already complimented Michael on a couple of his shirts, also made by Mom.

Leonard showed some of Vina's creations to his dear friend Elinor S. Gimbel, a scion of the Gimbel family. At the time, Macy’s and Gimbel’s were the two department store behemoths/leviathans. I use these two descriptors because both are borrowed from the Hebrew: Macy/Gimbel—de “oy” mit da “vey.” Leonard and Elinor were practically neighbors, both living in the upper 70s near 5th Avenue. So, Elinor was excited as well, and Michael, Leonard, and Elinor conspired to open some type of boutique in Manhattan. They had gone as far as having brochures and business cards printed. Michael recalls, “They were very fancy and done in pink!” Mom, humble as usual, simply couldn’t understand why they’d want her clothes, especially when there were so many other designers in New York City. But indeed they did, and their money talked. It said “Designs by Vina” were just as elegant and beautiful as any, even the designs coming out of France.

To get to the end of this winding story, Mom, meeting fierce resistance at home, gave up this dream. Realistically, this is a “tale of two cities.” The Silk Stocking District of the Upper East Side is not Bensonhurst. For Mom to open a store in Manhattan, when she lived behind our family’s store in Bensonhurst, well, this was a twain not joined, not back in the day anyway (early seventies). But, I can imagine Mom’s morale must have sunk when she then reported to the neighborhood “sweat shop” to sew someone else’s more pedestrian designs.

Mom met Leonard twice, but never met Elinor. Perhaps if she had—one strong woman of means inspiring a woman of talent and immense inner strength—the outcome may have been different. But we will never know.

Mom’s pain over this incident was evident in her sharing it. Georgette remembers:

Your mom told me of the time she was offered to go to work in Manhattan. Louie put up a fuss. That’s all I know. I don’t know any details of the story except that she was sorry she did not go, because who knows what that would have led to. She was creative and talented beyond being just good and great. She was superb—a marvel in clothing design.

Toni Caggiano, daughter of Large Mary, has a similar take.

Another anecdote, this from near the end of Mom’s life, comes from the artist, Sol Schwartz—a graduate of The High School of Music and Art (now Fiorello LaGuardia High) in New York City and a buddy of my cousins, Rosalie and Jim Mangano. Sol had a bunch of woven woolen “swatches,” which his wife was going to make into a sweater for their fifth great-grandchild. Sadly, his wife passed, and the project was passed down, but whoever was in charge was baffled. So, Jim and Rosalie recommended Mom, who put them together into a beautiful little outfit. Sol was gracious enough to write to me. I include his hastily written message for two reasons. First, it is a great example of New York vernacular. Secondly, Sol passed on Christmas day, 2015, five days before Julie’s passing, and so, the following is even more precious to me:

She did a wonderful thing by putting together a sweater my late wife had knitted but died before completing …. for her great-grandchild number five. Your mother not only put the entire sweater together, but made the most beautiful buttonholes that had not been completed as well. I bless her, and Jim and Rosalie Mangano for having done this. Our fifth great-grandchild is now wearing that sweater.

Sol was so thankful, he offered to pay, but Mom refused. So he gave her an autographed copy of his 2001 book, Drawing Music: The Tanglewood Sketchbooks (Tom Cross, Inc.), which features sketches of musicians performing at Tanglewood. I now own that dedicated volume, with lovely, expressive sketches—of the likes of Mstislav Rostropovich and Seiji Ozawa.

So, Sol became part of Mom’s circle. Vina could not just deal with people in an impersonal or professional context. They had to be family, and that list includes Tony the Fruit Guy, Sal the Tomato Man, Kim of Kim’s Fresh Produce, her hearing aid guy, and Chris Corritore who did her taxes. In most cases, there was an opportunity to make a creation for a new baby in the family.

During tax season I got this from Chris, who still does my taxes.

Words cannot describe what your mother meant to me. I always think of the smile that she brought to my face when she walked into my office. She really didn’t have to do taxes but I made sure to do everything I could to make sure [she got] something back every year—just so she could have a reason to sit with me.

I can only imagine her in her last days suffering but still having the patience, willingness and determination to knit my little girl [Isabella; I remember, Chris] the most beautiful pink sweater I’ve ever seen. I’ll always keep it as a memory.

Mom was not morbid, in spite of the knocks. This “old broad” aged gracefully, and was fond of saying, “A vecchiaia è na carogna,” dialect for “old age is a rotting putrid corpse.” I forgot the phraseology for the alternative of growing old, thinking it was something like, “Better to smell old than smell dead,” but, University of Missouri colleague, Professor Carol Lazzaro-Weis, suggested something more poetic: “ma per chi non ci arriva è una vergogna!” Or, “but for those who don’t get that far, it’s a shame!” (Tante grazie, Professoressa, that’s what Mom said!). Georgette, like most, loved Mom’s sense of humor:

I must say that for a woman whose life was not always smooth, she had a lot of humor. While visiting in the hospital with Joe [yours truly] and Phyllis [Florie’s niece], we got on the subject of death. We were saying that we are not so good at dealing with death. We were discussing sayings like “God wanted him,” or “It was his time,” or “She passed on,” and when we got to “Only the good die young,” Vina said, “What does that mean? That if you live to an old age, you are mean and rotten?” And we laughed and laughed. That was Vina—she always had the punch line. I’ll bet she is keeping them hopping in heaven. Miss her a lot.

They also miss Mom in the Holy Family Home (for the elderly and otherwise incapacitated). Toni Caggiano and Georgette went to the HFH to seek out administrators to get permission to hang a dedicatory plaque for Mom. A “second-in-command” was on hand, Denise Daniello, and as Georgette recounts:

Toni explained that she wanted a plaque in Vina’s name. The response, get this: “Do it. I knew Vina, a wonderful woman. I was sorry to hear that she died. She did an enormous amount of work here.” She was so receptive; Toni couldn’t believe it [and] started crying. I don’t think Toni expected such a response. Toni asked, “What about the new manager?” Denise said, “I’ll deal with him; I’ll talk to him. I’ll put the plaque in the recreation room, which is where she did a lot of work.” Toni started crying again. And so it went.

On May 31, some months later, there was a memorial mass for Mom at the home, coinciding with the mass that celebrates pregnant Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth. And after the mass, there was a lovely dedication of the plaque. The food spread had only a little to do with the fantastic turnout. Georgette is convinced that Mom “connived” to make sure that the right person dealt with Toni, and that the traffic on the Verrazzano Bridge from Jersey was light that morning.

If you have stayed with me this far, you will have noticed how intertwined are the lives of Mom, Georgette, Large Mary, Toni, Florie, Phyllis (and Florie’s mom, who was also Phyllis’ grand aunt), et al.— and the list is abridged for clarity and privacy. The aforementioned happened to share a hallway in a Bensonhurst apartment building, and those bonds have lasted for at least forty years. And, Carrie, Armida’s second husband’s mother, was also the mother of Tootsie, Julie’s late wife. So, Armida and Tootsie were sisters-in-law. If this seems gnarly, you can understand why we Italians are all just “cousins.” Mom, however, had all these relationships down pat.

Photo courtesy Georgette Adams

Georgette and Mom at the wedding of

Georgette’s niece, Ana Marie, center.