Читать книгу Vina: A Brooklyn Memoir - Joseph C. Polacco - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

3. Musical Interlude

ОглавлениеMusic was always a part of Vina’s life, and it very much extended to one of her two kids—younger bro’ Michael. Mom connected with music at all levels and all genres. This musical interlude takes us from Bensonhurst to Madrid, from the Moulin Rouge to the Bensonhurst Holy Family Home. Julie’s Grand Ole Opry and 86th Street music are part of the passing landscape.

Some may recall Shelton Brooks’ “The Darktown Strutters’ Ball:” “I’ll be down to get you in a taxi, honey. You’d better be ready around half past eight; now baby, don’t be late…” There was a more “ethnic” version—“I’ll be down to get you in a pushcart, honey.” Pushcarts were code for the Lower East Side, where Mom’s two older brothers were born. The Lower East Side was Chinatown, Delancey Street, and, of course, Little Italy.

Lou Monte had a southern Italian dialect version of the “Strutters’ Ball,” and Mom did a great rendition. As a volunteer in the Holy Family Home, she used to sing a duet of it with an old fazool resident—precious. You will note, dear and appreciated reader, that I tend to use Italian-Americanisms throughout my reminiscences. That dormant language virus was awakened by my frequent trips to the “old country” during Mom’s struggles. Okay, fazool? Every Italian kid knew of Pasta Fazool, a hearty dish of pasta con fagioli (beans and macaroni). Somehow, we called older Italians, the ones with the accents, “old beans” or “old fazools.” We may have liked to say fazool ’cause it started with F and ended with “ool,” and rhymed with a curse that translated as “Go sodomize yourself.” Or, less colorfully, Brooklynese may have elided “fossil” to “fazool.” Alas, there is no Royal Academy of the Brooklyn Language to rule on this. Royal Academy? Why not? Brooklyn is the County of Kings.

Mom was also pretty good with Eduardo di Capua’s “Eh Marie, Eh Marie,” popularized by, among others, Louie Prima and Lou Monte. Mom’s singing activities were in line with her being the unofficial entertainment chairlady of the Holy Family Home. She was also the chief seamstress—after all, what is an opera or musical without ostentatious costumes? She made the costumes for the famous Moulin Rouge can-can. Costumes by Vina were complete, so that the finale’s showy backward bow demonstrated tastefully ornate, embroidered, bloomer-festooned derrieres that belonged to the volunteers, Mom included. This awakened even the most moribund residents. Oh yeah, Mom did a fine tarantella as well.

Mom’s musicality ranged from the prosaic to operatic poetry. I was always amazed at how she was able to keep opera in her life, because we were not the family to traipse to the Met. We lived in three small rooms in back of our linoleum/carpet store on the famous 86th Street, the “Casbah” of open-air markets and small family businesses, all graced with shade from the West End El. My brother and I would sit in front of the store girl watching—especially rewarding in the summer, when the West End El disgorged people returning either from Coney Island or from Manhattan jobs. Stepdad quietly ogled—he not one to voice comments about the young ladies. But, he did not refrain from caustic, intentionally audible remarks about the passing characters. He had a way of casually insulting the Italians in Yiddish and the Jews in Italian— equal opportunity practiced to an art. He slipped these invectives, with a straight face, in the middle of face-to-face conversation. Of course, in keeping with the musical theme, Stepdad did many renditions of “Mala Femmina” (“Evil/Bad Woman” by Totò) from his perch in front of the store; see below. I am sure the ladies saw the irony of that song, a favorite of many males in the ’hood.

More 86th Street and music: Hypochondriac Abe was one of the daily passing characters. “What do I know? I just schlep haberdashery!” We all called him Healthy, a nickname coined by stepfather. Abe was deeper than a door-to-door peddler. For example, he loved the opera, and would frequent the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Back in the day, I am sure the BAM was an oxymoron to much of America. Healthy and Mom would occasionally sing a duet to an aria or two—Healthy with a look of ecstasy on his face. I recall their duets in front of the store. When I left home for college and grad school, it was difficult for me to buy my underwear in JC Penney or Sears. And it was difficult for Mom to escape to an opera, a real opera, in those days.

Healthy may have had a further cosmic connection to our musical lives. My Argentinian colleague, Ariel Goldraij, informed me that polaco meant precisely a Jewish door-to-door peddler in Argentina. Ariel helped further to weave this musical net by telling my brother of his love for the music of the Argentine, Astor Piazzola—“out of the box” tango composer and player of the bandoneón (modified accordion). Michael and Ariel connected because Piazzola was already one of my brother’s musical heroes.

A couple of years after Mom was widowed, she got to see a whole opera in a truly a beautiful world-class venue. During my sabbatical in Spain in 2000, she and my kids visited over Christmas, and I was able to cop a couple of ducats to Verdi’s Il Trovatore at Madrid’s Teatro Real. However, our entrance was Brooklyn all the way. We took the subway (Metro) from my working-class neighborhood, and she entered El Teatro in an elegant dress she made herself, carrying her own libretto. She had to be the only person, ever, to bring to the Teatro Real a libretto from the New Utrecht branch of the Brooklyn Public Library. She was thrilled by the performance, but not by the crowd, which she considered boorish (not the word she used). And, back in Bensonhurst, she dutifully returned the libretto, and on time.

Opera in Bensonhurst could be a selection of arias at the confraternity hall of the neighborhood St. Mary’s parish, a street duet with Healthy, old recordings of revered Neapolitan soprano Enrico Caruso, PBS TV/radio shows, or even a very well-planned surprise party in the ’hood. Mom planned Stepdad’s seventy-fifth surprise birthday party for years, scrimping and saving, doing seamstress jobs at home, etcetera. She pulled it off. It was at Scarola, a Bensonhurst restaurant where waiters/waitresses were aspiring opera singers. One was the owner’s son.

What a night! Stepdad was cranky at the beginning. “Why do I have to take pictures for my niece’s wedding shower?” he moaned in the back seat of our car on the way to the restaurant. But, after the initial shock, he had a fantastic time. I still have visions of him dancing in all his finery—yes, he always dressed to the nines, even as a party photographer. The operatic pieces by the service staff were beautiful and poignant. I wished I could sign them to contracts on the spot. The party? Well, we were all there. Don’t know how Mom did it—the finances, the secrecy, the arrangements, the pretexts for our all being in Brooklyn at that time. While Stepdad had a grand time, he did tease his Vina about being “sneaky.”

I suppose Mom’s musicality was handed down to kid bro’ Michael. We both loved Elvis and Johnny Cash, even before their “coming out” on The Ed Sullivan Show. Michael very much took to country and western. He perfected his twang, and he learned the Elvis hip swivels. Amazing to me, he taught himself the guitar. And, I am not sure that he ever learned to read music—he composes to someone who writes it down. Indeed, there was a cowboy yearning for expression inside this ragamuffin Italian street kid. And today Michael (Polacco, Grandi, Grandé—your choice) performs out in Arizona where he and his wife Diane own a horse ranch: Amber Hills Arabians, featuring Revelry, Top Ten Stallion and stand Arabian Sire of Significance. But, the locals dig his Brooklyn sagas, and some of them are true. In Michael’s musical prime he shared long tours with John Lee Hooker, Canned Heat, and Bedford-Stuyvesant native, Richie Havens. He had shorter stints with others.

So, back to Bensonhurst—as the human caravans of our youth trudged along 86th Street, they sometimes had to part into separate currents around Michael, with his guitar, hip gyrations, and Scotch tape-enhanced Elvis sneer. Understand, 86th Street was the Wall Street of Bensonhurst mercantilism, but nothing was really awry.

So, Vina, your kid is out front making a spectacle of himself. Her face said that he was doing what he loved, near home, not hanging at the waterfront with the likes of “Rampers” Jimmy Emma or Sammy “the Bull” Gravano.

In the old days, 86th Street did quiet down on Sunday evenings—it never does now—when some a capella groups would take advantage of the unique acoustics of the West End El and its steel support girders. The El structure, however, was not so much a capella (chapel), but more of a cattedrale (cathedral ). I wonder if Dion and the Belmonts sang under an El in the Bronx. Whatever, Michael and I were each a “West End El Niño.”

I picture those 86th Street scenes, and music arises, alla mode di Dino De Laurentiis: Vide’o mare quant’è bello; spira tantu sentimentooooooo (Look at the sea, oh how beautiful; it inspires so many emotions). These Neapolitan dialect lyrics are from “Torna a Surriento,” or “Return to Sorrento,” by Ernesto De Curtis, and Stepdad often spouted them whilst sitting in front of the store, his back to Gravesend Bay. “Torna a Surriento” was part of his medley. And, as mentioned above, another important component was “Mala Femmina," popularized by Jimmy Roselli. Stepdad could never understand why Jimmy did not supplant Frank Sinatra. Roselli died in 2011, at age eighty-five. Mannaggia (dammit), time goes on. I see a parallel between the Sinatra-Roselli and Enrico Caruso-Mario Lanza axes. Roselli was born in Hoboken, NJ, five doors down from Sinatra, who was ten years his senior. According to the Mario Lanza Institute and Museum: “The greatest of all tenors, Enrico Caruso, passed away on August 2, 1921, and on January 31, 1921 in the heart of South Philadelphia, Alfredo Arnold Cocozza (Mario Lanza), the son of Italian immigrants, was born at 636 Christian Street.” So, Lanza was not born on the day that Caruso died, as I was always told, but close enough—same year, at least.

Neither Roselli nor Lanza reached the heights of his respective idol.

This chapter is closing out like the fadeout of the Beatles’ “Hey Jude.” Let it be said here that Mom had a great voice, and that she could never understand why I sang like a bullfrog. Also, for the record: My own Nonna Nunziatina, Mom’s mom, was virtually deaf, but she could hear those scratchy recordings of fellow Napoletano, Caruso.

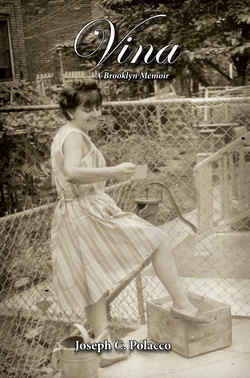

Polaroid Photo courtesy Polacco family archives

Brother Michael serenading Nonna Nunziatina in the kitchen in the back of our store, early 1960s. A Nonna may have humored Michael on occasion.