Читать книгу Vina: A Brooklyn Memoir - Joseph C. Polacco - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4. Large Mary and the Little Butterfly

ОглавлениеShe was larger than life. She was also large, and I apologize to her beautiful daughters for the sobriquet “Mary Fat,” but they knew. Mary asked my two-year-old daughter, “Do you know who I am?” and the wide-eyed innocent answer, “You’re Mary Fat,” was both embarrassing and disarming. Mary, you see, loved children—all children. Her grandkids, nieces and nephews, and neighborhood kids all knew they had to pay with a pint of cheek blood, because Mary had to pinch them. “Come here, so I can eat you alive!” Mary regaled them all with love, but the treats were the real payoff.

On the south side of 86th Street, on the block bordered by 21st Avenue and Bay 26th Street (for the GPS-enabled), lived a concentration of incredible ladies—Large Mary Napolitano, Jeanie (Gruff but Gracious) Gallo, Georgette Seminara Adams, and her aunts, Rose and Mary Seminara. Some time after the passing of Large Mary, these ladies formed a Bible study group that also included Mary’s daughter Toni, Florie Ehrlich, and Mom. Many Mary stories are epic, if not biblical, and they are legion and were often exchanged at the Bible Study.

Mary had show biz in her blood. Her face was angelic, and I was told she was a beauty in her youth. Indeed, to me, she radiated beauty. Her uncle, her father’s brother, was the famous-for-his-time “Farfariello.” The Little Butterfly, Eduardo Migliaccio was a mainstay of immigrant Italian theatre. Yes, in addition to the Yiddish theatre, there was a not-as-well-known Italian one, and doubtless others in the Lower East Side. Bob Hope honored Farfariello. Farfariello based some of his skits on real-life Migliaccio family escapades. The Little Butterfly’s comedy was slapstick, and he had to project his voice, often in a falsetto, over the whole raucous audience. Mary also had a booming voice, and she was an extra in some of her uncle’s skits. I remember her narrating to Mom and me a funeral story, a true story, in which the black-clad professional mourners would wail, “Who’s going to cook the fish?!” They wailed, and Mary boomed the retelling. I won’t even try to write the lines in the dialect Mary used.

Mary loved Broadway. But, of course, it was in her blood. Mom told me at least three times about their taking a car service to see a show. The driver shows up and sees three ladies. Two are petite Mom and diminutive Carrie, the mother-in-law of Mary’s daughter Armida. Carrie lived with Mary. The third lady is Large Mary, and the driver is horrified. He tries to drive away, but they convince him to make the trip. I would wager he avoided the old cobblestoned West Side Highway. Après-theater, they try to hail a cab, to no avail. Finally, Mary hides, they grab a cab, and then Mary appears. Same scenario. But Mary, sitting in the front seat, charms the cabbie and, after landing safely in Bensonhurst, Mom gets out and Mary and Carrie invite the driver for a frappe at Hinsch’s Greek Diner. Yes, I know, Hinsch’s is not a Greek name, but in Brooklyn most diners are/were Greek-owned. Now, mind you, Hinsch’s is on 5th Avenue just off 86th Street, fully seventeen big blocks from Mary’s house, and Mary’s husband Jimmy has no idea of the whereabouts of Mary (and Carrie). Ahh, being married to a starlet has its drawbacks.

Not too much of a surprise that Mom connected with Mary—for one thing, they both had generous hearts. One Saturday morning, Mom and dear friend Bianca were returning from errands, and they decided to drop in on Mary. Remember, this was the Bensonhurst of old—dropping in, unannounced, was expected, and the folks “passed over” knew of the offense. So, Mom and Bianca spot a guy hiding behind a tree on Bay 26th Street, just as Mary’s husband Jimmy is leaving to walk the dog. Soon after, the mystery man enters, and Mary proceeds to supply him, hurriedly, with grated cheese, cans of imported tomatoes (pomodori pelati), and various other items. The mystery man was Carl, the husband of Flavia, daughter of Farfariello. Mary was an easy touch, and hated to see cousin Flavia go through tough times. Mom and Bianca were also charitable ladies, but they scolded Mary for being so devious. Mom relayed this story to Toni, who later told me, “Well, that was my mom, a giver, and sad to say, there were takers.” My stepdad tried to intervene on Mom’s generosity, ’cause he looked at the world as takers. And I think Jimmy—Toni’s stepdad, from the old country, and with a suspicious facial scar—felt the same way. Yes, experience proved them right on a few occasions, but better to suffer the takers, while helping the truly needy, than not help at all. I, Joe Polacco, said that, and Mom agrees, even now.

Okay, I am using terms like “angelic” and “generous” and “charitable” to describe my mom, everyone’s Aunt Vina. But, she also had immigrant peasant toughness. One hazy, opressively hot summer afternoon of particularly bad quality air—the kind that used to hurt your chest on deep inhalation—I was hanging in front of the linoleum store, and the upstairs lady comes down, trying to escape the heat. There was bad blood between the upstairs lady and Mom. (At the time, I’m not sure we owned the two-story building; the upstairs lady was either our tenant or neighbor, but in any case, we still lived in back of the store.) The upstairs lady starts to bad-mouth Mom to Stepdad Lou. To his credit, he says, “You can’t shine her shoes.” Things get nasty, and I remember the upstairs lady saying, “Vina cooks with a lot of grease; that’s why your kids have pimples!”

Mom is now coming home, drudging off the West End after a day in a hot garment union (sweat) shop, and she gets wind of the last comment. “Oh, I give my kids pimples?” One thing leads to another, and then a tremendous fight—I mean a no-holds-barred lady fight—breaks out. Mom proceeds to kick the lady’s butt, and is wiping the hard mean sidewalk with her. Three patrol cars show up; the guys inside were beat cops, and were known, so this was more community relations than law enforcement. The whole scene was more entertaining to the passersby than my bro’s Elvis renditions. Man, I saw a woman capable of turning her love and caring into animal ferocity against someone who would slam her kids and the care she provided them.

I never asked Mom about that fight, and I am sure she would have been very embarrassed even to acknowledge it. Happily, my three hours of recordings of her during her last six months were filled with non-violent stories, recipes, and laughs.

Mary Fat and Aunt Vina were just two of the very large women in the ’hood. Taking care of others was what the ’hood did. There were street folks who were “developmentally challenged,” and they always seemed to find food and support and shelter. They were part of the ecosystem. One of my bro’s friends, upon seeing a down-and-outer slurping a bowl of hot soup in back of our store, came out with, “What is dis, da Brooklyn Rescue Mission?” This was mentioned in the Introduction, but it bears repeating: Brooklyn Rescue Mission was the name of my brother’s first CD.

I do not want to paint a picture of “My Sainted Mother.” All Italian mothers are sainted—the “mala femmina” referred to moglie (wives) or innamorate (girlfriends). And all mothers, including Mary and Vina, would drop their wings at times, and recognize human imperfection. For instance, some of the friends my brother and I brought home were scassigazzi, and they were probably better than the ruffiani. The former were just “ballbusters,” but the latter, worse—two-faced sycophants, a little bit like Eddie Haskell. Ballbuster is a loose translation—scassigazzo referred to a more singular aspect of male anatomy. But even these deviant characters received Mom’s attention, though she could see through them. The same goes for Large Mary.

Finally, I cannot close a chapter on Large Mary without a mention of her three beautiful daughters, Triple A-rated: Amelia, Armida, and especially the youngest, Antonina (Toni Caggiano). They were great supporters of Mom, as well as recipients of her support. Toni was also a regular at the famous Bay 26th Street Bible Study. And now, Toni’s three daughters have bestowed eight beautiful grandchildren upon her. Toni carries on the tradition of strong and loving Brooklyn women, and I won’t call her a “flat leaver” for moving to Jersey.

This from Toni:

One year after my mom passed when we lived in Brooklyn, I had to have a birthmark removed from my back. I was recommended to a doctor in Manhattan. I went with my husband Vinny, and was told to return in two weeks to have the stitches removed. The first available appointment was 7:15 a.m. My husband worked in New Jersey, so I thought I’d go myself and not have him take off work again. At 6:15 a.m. my doorbell rang, and there was Aunt Vina. She had walked from her house at 77th Street to mine on West 3rd Street (a considerable walk) to go with me, because she did not want me to be alone—because I didn’t have my mom. That was her, always going the extra mile. We made a little day of it, and because of her, I looked at Manhattan in a different light. She made me notice the tops of buildings, and she showed me the Garment Center statue of the seamstress at the sewing machine.

Twenty years later, she had to go to her primary doc and bring her mammogram—not an easy feat since the mammo was at 94th Street and the Health Insurance Plan Center was at 67th Street and 10th Avenue [both in Brooklyn]. I surprised her, picking up the mammo and taking her to the doc. She was so grateful. She never asked for favors, but she could thank you for giving her one.

But wait! There is more from Toni:

Aunt Vina loved a bargain. My niece was getting married, and [daughter] Cara was her flower girl. My niece had a picture of a dress she wanted Cara to wear. It had a layer of lace on the bottom of the hem. This was also Cara’s first communion time, and without benefit of a pattern, Vina made the dress with a detachable lace hem that we removed for her first communion. The entire cost of the fabric was twelve dollars, and she wore the dress twice. She looked beautiful, and no one had the same dress. Of course we did lunch after the fabric store, at the now-famous half sandwich shop on 18th Avenue.

All in all, it was always a great day when I was with her—she was always good company and great fun. She filled a big void in my life, with her old world wisdom, cheerfulness, and caring. She was a blessing in my life. I hope you, Joe, get comfort in knowing how loved she was. Boy do I miss her.

So, Aunt Vina was big enough to fill, at least partially, the void left by Large Mary. And, I add that Toni was instrumental in getting the Holy Family Home to memorialize Aunt Vina’s contributions.

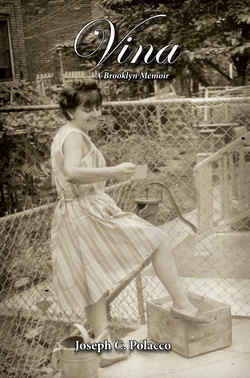

Photo courtesy Toni Caggiano

Large Mary, in a pensive pose.