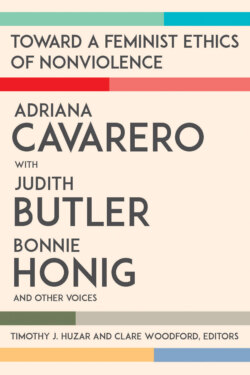

Читать книгу Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence - Judith Butler - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Cavarero and Feminism

ОглавлениеKnown for its strident stance on sexual difference, female separatism, and militancy, Italian feminism can seem confusing and at times even contradictory to an Anglo-American audience. Similarly to the sexual difference theory emerging in Anglo-American feminism in the 1970s and ’80s, Italian feminists mobilized sexual difference to intervene in major philosophical debates and sought to use it as a tool to free women from their entrapment within these debates, enabling the construction of an alternative symbolic order apart from phallogocentrism.

References to sexual difference today typically evoke the essentialism/constructivism feminist debates of the ’70s and ’80s, which emerged from a prior debate between “liberal” and “difference” feminism. In schematic terms, liberal feminists argued that women were formally equal to men and should have the same rights as men. In contrast, difference feminists, including feminist women of color, emphasized that women are different from men and should not have to be the same to warrant equal status. For many feminists, this then triggered discussion regarding the status of this difference—were women different in essence or just through social construction? In contrast, Italian feminism could be understood as sidestepping this debate by instead seeking to develop a position that refused either pole of the essentialist/constructivist binary.7

Indeed, il pensiero della differenza sessuale (sexual difference theory)8 was shaped less by the opposition to liberal feminism that influenced the development of feminism in the U.S. and rather more by its response to the traditional split between conservativism and communism in 1970s Italian politics as well as a new post-Marxist leftism still imbued with misogyny. Invitations for women to join with men politically, despite purportedly being on equal terms, ended up dominated by male perspectives.9 As a result, the target of sexual difference theory was not primarily liberal equality feminism, as was the case for American sexual difference feminism, but any notion of politics based on a notion of equality as sameness. This was because equality as sameness reinforced the same old gender hierarchies. As a consequence, Italian feminists were particularly attuned to the problem of male bias presented as a supposed neutrality. To be able to oppose this, and inspired by the work of Luce Irigaray, Italian feminism had to assert that there was something that was not man, that was typically referred to as “woman.” This something, inasmuch as it was not man, could be understood, in Gisela Bock and Susan James’s words, as “a primary, originary female difference [which] has, in all areas of social life, been homologized or assimilated to a male perspective which hides behind a mask of gender neutrality in order to subordinate women.”10 This was an understanding of sexual difference that was neither based on the claim that there is a female essence that we can know nor simply repeating the sexist and patriarchal imaginary of women as different and lesser. Instead, it provided an assertion of female difference as different in a positive sense, in a way that did not need men to create the conditions for women’s existence or self-understanding.

The argument for sexual difference asserted that the sexed female body is not only something that is perceived to operate within and to significantly affect our contemporary world, but is an irremediable aspect of existence. This is why Cavarero stresses that sexual difference is “given.” Whether we like it or not, our bodies are sexed: to exist as an embodied being is to exist as a sexed being, even if the meaning and significance of this “sexedness” is affected by normative conceptions of sex/gender. Cavarero expresses this through her primary distinction, borrowed from Hannah Arendt, between who we are and what we are.11 Our sexedness is integral to who we are—to our embodied uniqueness—whereas the meaning and significance of this sexedness describes what we are; what we could otherwise call our “identity.” But in either case, what is crucial for both Italian sexual difference theory and Cavarero is that our sexedness is a necessary part of our existence. There is no neutral terrain that we can inhabit free of our sexedness, and neither is our sexedness merely a discursive inscription on the otherwise inert matter of our bodies.

Cavarero acknowledges that it may appear as if both sexes find themselves in the same quandary. If we pose sexual difference as secondary and nonessential, then it would seem that women and men alike find themselves already spoken, defined, and controlled in the social sphere. Yet, like many other feminist thinkers, Cavarero emphasizes that any idea of a neutral, non-sexed identity is actually already a space taken by Man. The neutral image of the human is always already male. If women are to appear, they can be neither male nor neutral; women find themselves obscured by a presumed neutrality that also operates at the level of their sexedness. Those designated women are subordinate to either Man or to the so-called neutral being. Consequently, Italian difference feminism asserts that to resist the fact that the space of neutrality is already taken by Man, women have to find a way to appear as women but to refuse to do so in the way that has always been demanded of them—as a subordinate. For sexual difference feminists, it is only by asserting something called sexual difference that, in Cavarero’s words, we open up “the possibility of the woman to speak herself, think herself, and represent herself as a subject in the proper sense of the word.”12 Thus because woman as a nonessential being risked overlooking the exploitation of women, sexual difference theorists preferred to risk the essentialism that will always accompany their assertions of difference. However, it is worth acknowledging that sexual difference theory does not need to assert difference as an essence in any ontological sense. It can simply provide a focus on who women are at any point in history,13 understood predominantly as the experience not of a concrete essence of what it is to be a woman but just what it is to be that which is separate, that which is not man. As Fanny Söderbäck notes, “The crucial point … is that all individuals are sexed, not that there are or should be only two sexes.”14 Thus, difference feminism seeks to acknowledge our inability to escape the body, even though difference is not intended here as a ground.15

Indeed, although Cavarero’s work, especially her early work, has often appeared to take an essentialist position, she clarified in a 2008 interview with Elisabetta Bertolino that where she has treated the body as an essence, this was done so strategically.16 This may appear as a change of approach but is less surprising when we realize that even in her earlier work Cavarero was uneasy with the limitations of an abstract understanding of “woman.” This was signaled by her concern that any position of strong or positive sexual difference that seeks to define what woman is may lead to the opposing problem of mirroring the subjection of woman that is affected by man.17 As Diana Fuss suggested in her assessment of Spivak’s “strategic essentialism,” such a strategic approach could be seen as a “ ‘risk’ worth taking,” since although strategic essentialism can be dangerous “in the hands of a hegemonic group,” it can, notwithstanding, be a powerful tool for subalterns to subvert and displace current power relations.18

Despite her unease with essentialism, and particularly pertinent for the dialogue in this volume, Cavarero’s sexual difference theory did initially establish itself in opposition to both liberal and what she referred to as “postmodern” philosophy, specifically represented by the work of Judith Butler.19 Cavarero’s concern was that both liberal and postmodern feminists unwittingly used the metaphor “woman” from a male perspective and thus ended up only responding to problems generated by the male subject of philosophy.20 As Richardson explains, for Cavarero both liberal feminism and postmodern feminism stressed “the priority of language over the ‘fact’ of the sexed body.”21 Cavarero therefore argued that despite their apparent differences, the postmodern “attempt to fragment the subject was ‘simply the other side of the coin to the [liberal] emphasis on the “one.”’ ”22 For Cavarero, postmodern feminism did not escape the sexing of its multiple or fragmented subject as male. While recognizing the problems of women’s subordination, it underplayed the force of sexual difference. It recognized the complexity of female oppression but denied recourse to address this from the position of actual women. Consequently, Cavarero’s intervention between liberal (or in Cavarero’s words “metaphysical”)23 and “postmodern” feminism was to insist that neither accounted for the singularity of each woman; that her embodied, sexed, lived experience—who she was, or her uniqueness—was rendered “superfluous” (for liberal feminists) or “a kind of trick” (for “postmodern” feminism).24

Furthermore, while much poststructuralist feminism owes a particular debt to Freudian psychoanalysis, many Italian feminists, Cavarero included, reject this tradition, despite having been influenced by Irigaray. For Anglo-American readers this may be seen to contribute to Cavarero’s over-idealization of the maternal and failure to acknowledge the ambivalence and antagonism in the mother-child relationship.25 On this reading Cavarero overlooks the possibility of disavowal or refusal in characterizing the apparent opposition between inclination and rectitude. Indeed, these concerns are at the crux of Honig’s intervention, which reads Cavarero’s feminism alongside Freud to emphasize the more sinister side of maternal care.

Yet, could we read sexual difference theory as complementary to the “postmodern” project of undermining the binary between construction and essentialism?26 Indeed, both approaches begin by denying that there is something that “women really are.”27 Further, as Bock and James argue, sexual difference theory opposes the threefold assumptions upon which the essentialism debate rests. First, “the over-neat distinction between biology and culture that underpins the Anglo-American division between sex and gender and incorporates a vision of women’s bodies as separable from culture”; second, that we could avoid essentialism by assuming that women are fundamentally different from men, which is no less essentialist than assuming that women are fundamentally the same; and third, that we cannot know of “any essence of woman which is independent of their past and present conditions.”28 This could be seen to demonstrate that the theory of sexual difference shares with so-called postmodern feminism a refusal of sameness and a refusal of neutrality.

Although sexual difference theory insists on the difference that is women’s experience, which is always taken to be different from men’s, the refusal to engage in a debate about what women are reveals that this focus on bodily difference was not intended as an attempt to tie a body to its biology. It conversely sought to “address the problem of how to avoid fixity, and the danger of tying women to their essential natures, rooted in biology or the psyche, while still insisting on the salience of the sexed body to subjectivity.”29 Hence Italian sexual difference theory came to be characterized by the significance of feminist materiality as a beginning point to account for the privileging of a presumptively masculine figure at the heart of the philosophical imaginary of the Western tradition. This led many Italian feminists to emphasize on the one hand the necessity of separatist movements to create the conditions from which an alternative symbolic order could be constructed and, on the other, the focus on the imagery of the maternal as a key battleground for establishing this alternative symbolic.

With regard to the relationship between Cavarero’s feminism and the work of Judith Butler, it is true that Butler’s work was challenged by many sexual difference theorists, including Cavarero. However, the objections were largely premised on a misreading of Butler’s theory of performativity as assuming that sexual identity could be chosen at will. Butler’s argument that gender is constructed did not imply voluntarism. Social construction is constitutive of the whole realm of subjectivity, not just one individual experience. Thus, gender cannot be dispensed with at will, since our very social existence as meaningful beings requires us to operate, at least to some degree, within the confines of gender norms.

Responding to the exclusions within both feminism and lesbian and gay politics of the ’70s and ’80s, Butler’s motivation was to understand why, while we seem to need gender identity, it will always exclude. As such, she wanted to avoid mobilizing around a new theorization of identity, however radical, and instead sought to loosen the way that gender identity affects us. She argued that the potential for resistance and change does not lie in a refusal of identity, nor an alternative identity, but instead in the renegotiation and subversion of norms. Drawing on J. L. Austin’s speech act theory, as well as the work of Jacques Derrida, Butler argued that gender is produced by repetition. She acknowledged that perfect repetition is never possible, since our gender identities are always to some extent a parody of an idealized norm. Yet it is precisely because of the impossibility of perfect repetition that Butler finds a space in which gender norms can be challenged. By repeating norms in a “wrong” manner, it may be possible to loosen the strictures of what counts as either male or female and the constraints that gender identity imposes on our lives. This is not to dissolve sexual difference or to multiply sexual difference in a way that completely dissolves woman as a subject position; rather, it could help de-binarize sex/gender and decenter its restrictive and controlling social function. Would it be too much of a stretch to argue that in this way Butler’s work could be seen to develop the project of sexual difference theory even further, as she opens up the idea of that which is not man, beyond what is usually referred to as woman?

Reservations about Butler’s work do remain for theorists of sexual difference, particularly regarding whether it indirectly diluted feminist struggle and prioritized sexuality as the dominant mode of relationality, thus displacing care or dependency.30 However, Butler’s position among Italian feminists was considerably enhanced by Cavarero, who engaged with Butler’s argument as early as 1996, when she wrote the Preface to the Italian edition of Bodies That Matter. Furthermore, Butler’s work on vulnerability and precarity, developed in part in conversation with Cavarero (see Bernini’s étude, later in this volume), addressed many of these initial concerns and helped to emphasize that both were circling the same issues from different perspectives: how to resist liberal individualism and avoid androcentrism without prioritizing certain sexual identifications over others.

Honig’s relation to these two thinkers charts a rather different trajectory. Like Butler’s work on performativity, Honig’s reading of Arendt was also inspired by the performative in Austin. While Butler’s extension of the theory of performativity to sex/gender inspired Honig’s radical reading of political action in Arendt,31 rather than simply apply Butler’s theory Honig has developed a unique feminist theory of her own, navigating the tension between her poststructuralist approach and her longstanding sympathy for Cavarero’s sexual difference project. Indeed, Honig’s “agonistic sorority”32 operates in the very space between—in fact, the space opened up by—this “postmodern”/sexual difference debate.

For Honig, recognition of the complex dilemmas we encounter in political theory are exemplified by, though not limited to, debates around sex and gender. Her interest is in the way that any such agonistic struggle “exposes the remainders of the system”33 by revealing how systems of knowledge or power minoritize those who do not fit their parameters. Instead of opting to resolve disagreement, Honig seeks to radicalize it,34 holding disagreement open and exploring it—itself a political gesture that refuses the closure so often sought by political theory. With respect to the feminist debate that concerns us here, Honig emphasizes that each position has opened something up in its agonistic rival that may elevate or extend those who confront it, and open new unimagined possibilities for worldbuilding.35

By tracing the development of Cavarero’s feminism in this section we have seen how her perceived initial distance from Butler has lessened over time, and that Honig’s agonistic feminism provides us with a way to productively map their differences. We will see in the next section that Honig’s more direct engagement with agonism leads to her effort to take an alternative path to Cavarero’s heterotopian feminism. This also generates Honig’s distinctive critique of the politics of nonviolence that has come to unite Cavarero and Butler’s recent work.