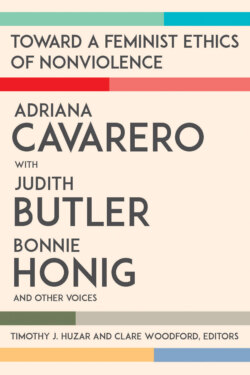

Читать книгу Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence - Judith Butler - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Inclination in the Work of Adriana Cavarero

ОглавлениеWe begin our brief introduction to Cavarero’s work with the guiding image of Leonardo’s Madonna, central to Cavarero’s account of a postural ethics of nonviolence. The painting is an unusual portrayal of three figures from the Christian Holy Family. Rather than the child Jesus with his mother, Mary, or also with his father, Joseph, it shows Jesus and Mary with Mary’s mother, Anne: two mothers, two children, Anne with her daughter, Mary, sitting on her lap while Mary’s child, Jesus, plays alongside. It inspired Cavarero because, in its time, it was a subversive image of motherhood despite its apparent orthodoxy today. What may seem an innocent decision to place Jesus at Mary’s side contravened the dominant convention that required the child Jesus to be seated on Mary’s lap, held in her arms but with his back to her, facing the viewer. Mother and child were not meant to look at one another. The same convention dictated that all figures should be structured vertically. Instead, Leonardo portrays all three figures inclined and twisted around each other. In Cavarero’s words the painting

breaks with this system of symmetrical verticality, presenting a mother who is face to face with her child; a child whose head is twisted back to face the one who visibly tilts and stretches out to support him; and an Anne who observes them both with a smile. The asymmetry of this portrait, modulated as it is by inclination, translates nicely into the movement of a relationality that reflects the everyday experience of the maternal rather than the monumentality of the sacred.3

It subverts the authoritative conventions of its time and in doing so emphasizes maternity and the dependence of the child—here representing for Cavarero the vulnerable more widely—on the care that the mother provides.

It may seem strange to readers from an Anglo-American background that Cavarero chose a religious image at all, for even this once subversive image appears today as orthodox, traditional, and stereotyped. But Cavarero is not using the image in a religious context. Nor does she repeat traditional tropes of motherhood as passive or subordinated. Rather, she seeks to “strategically exploit” the imagery of motherhood to think differently about the everyday postures of our lives. The painting is her “point of departure,” an inspirational provocation that upends the everyday privileging of the “upright” and the “straight” in morality and philosophy as unnatural, artificial, and strange. As we read in the beginning epigraph, she is not simply replacing the archetypal straight man of philosophical and moral thought, but instead complicates the archetype, displacing it in “a multiplicity … of directions.”

Despite distancing herself from the religious significance of this image, Cavarero still mobilizes the religious element of this painting in two ways. First, the love characteristic of an ethic of inclination is the “enigmatic” love of Leonardo’s Madonna.4 The sense of mystery that this evokes is romantic, poetic, but, given its context, can never be totally separated from the spiritual or the religious. It draws on a particular Christian formulation of an ethical relationship of care for the other. Second, the use of this image shows maternity as more human than convention dictated, and yet still sacred. It holds a place in our symbolic imaginary, so much so that Cavarero uses it, as cited in the epigraph, to beget a “fundamental schematism” founding a new order.

A feminist ethics inspired by a religious image representing maternity may seem incongruous today. However, discussion of religious iconography is not irrelevant to the world of the twenty-first century. The appropriation of cultural images and the imaginary of the maternal are a ripe political battleground, given that years of feminist struggle are at risk of being undone by a vicious backlash that blames feminism for many, if not all, of the world’s ills.5 While this battle over the appropriation of religious imagery may resonate in some countries or communities more strongly than in others, the logic it utilizes is that of political contestation. Cavarero recognizes dominant social imaginaries as sites of struggle.

In this light it is helpful to dwell for a moment on the wider context and key debates that shape the terrain on which the dialogue of this book intervenes. Italian feminism has long struggled over the imaginary of motherhood in Italian life. Cavarero strikes at the heart of a certain hypocrisy in Italian politics, but one that is also identifiable beyond Italy’s borders, as noted by Janice Richardson in 1998:

Given the ubiquity of portrayals of the Christian mother and son in Italy [Cavarero] describes Italian feminists’ particular desire to resymbolise motherhood and birth. In so doing she theorises a link between the “sickly sweet” sentimentality popularly associated with portrayals of motherhood and the blindness of metaphysics to the (flesh and blood) mother.6

In the face of those who abuse religion and motherhood in the interests of misogyny, patriarchy, and inequality, Cavarero’s heterodox reading restores importance to the oft-subordinated role of motherhood. It reinclines the maternal and the religious toward another ethic. It reanimates a tradition that valorizes natality and maternity, from Arendt to Irigaray, as a political resource for thinking relationality, inclination, and vulnerability.

A reader may think the image chosen by Cavarero is still too stereotypical: that it reinforces rather than troubles the sexual stereotype of women as caring and maternal. In response, note that her methodology of stealing from within the very tradition that oppresses developed out of her engagement with Italian feminist movements both within and outside of the academy. In tracing the trajectory of Cavarero’s project and placing it in the context of Italian feminism, we may better come to understand the stereotyping at play here.