Читать книгу Toward a Feminist Ethics of Nonviolence - Judith Butler - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prelude

ОглавлениеTIMOTHY J. HUZAR

I met Adriana Cavarero halfway up a mountain in Sicily. People from across Europe had convened to talk about life, politics, and contingency; Cavarero, as a political philosopher and the foremost Italian feminist scholar writing today, was among a number of keynote speakers asked to contribute their thoughts.1 As a student of the relationship between violence and politics I was aware of Cavarero’s Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence; however, I hadn’t encountered the rest of her oeuvre, and the book, in isolation, had been swept up in a large number of texts I was reading in the early stages of my Ph.D.2 Cavarero’s talk was in Italian, and having no Italian, I was left with the sonority of her voice and her embodied communication; Cavarero at times sitting behind her desk, at times standing and leaning in to the audience, her paper discarded as her oration carried her into the room, focusing in on the interventions from those who contributed their thoughts, provocations, and disagreements. In between the talks people would gather in the courtyard to smoke and drink coffee or beer, sheltering under the shade of a grafted citrus tree from the relentless midsummer Sicilian sun. I spoke to Gianmaria Colpani and other students of Cavarero’s about my thesis, and they introduced me to some of the key themes that can be found across her work: not only the extrapolation and exploration of horrorist violence, but a prolonged engagement with vocality, feminist materiality, narration, and, above all, Hannah Arendt’s category of uniqueness.3 It became clear that there was a glaring gap in my research, perhaps accounted for by the sway of the biopolitical tradition in Italian political philosophy that Cavarero sits in proximity to, yet apart from. Toward the end of the first evening Cavarero and I spoke briefly, but it wasn’t until the second evening, when enough time had passed for people to get to know one another and to relax some of the unspoken proprieties that lie just below the surface of the social world of academia, that a sense of who Adriana Cavarero was became more apparent.

One of the many themes that can be found in Cavarero’s work is an insistence on a respect for the palpable truthfulness of the everyday: that in people’s everyday experiences something of the world is revealed to them, just as they continuously reveal themselves to the world. This means that despite her classical training and her sophisticated and extensive engagements with some of the major debates in twentieth-century continental philosophy, Cavarero’s work insists that meaning is not to be sought in the rarified conceptual worlds of great thinkers, but is present in the ordinary world for anyone to see or hear if they only knew how to see or hear it. Her work gives us the tools to make these sensory adjustments: each of her books functions something like an eyeglass or a hearing aid that we can use to help learn what it is to see meaning in the everyday and unlearn the compulsive turning to those tropes dear to the Western tradition that are now wearing thin.

During the evening of the second day of the summer school, Cavarero demonstrated that her skill at manifesting the meaning present in the everyday was not restricted to her academic work. As the sun set and people drank and smoked, Cavarero suggested that song might be a good tonic for the heady metaphysics that were given form in the reasoned dialogue of that day’s talks and discussions.4 With the help of Adriana’s enthusiasm, as well as the limoncello and grappa that began to flow at the bar, people stood or sat in the now star-lit courtyard, voices raised in song reverberating around the centuries-old stone walls. Some of these songs were known by all, and so the soloist quickly became a member of the chorus, while others began as solo and were slowly joined by other people as they either learned the patterns, remembered the words, or clapped to the rhythms. Other songs were known only to the singer and so stayed as a singular voice. Yet even here, this was a singularity destined for the ear of another, or in this case many others; and the sociality that was convoked in this space—or what Cavarero would now call the pluriphony—was palpable to all those present.5 Cavarero, for her part, performed an operatic duet from Mozart’s Don Giovanni—“Là ci darem la mano”—embodying both masculine and feminine parts and, in the process, providing further evidence for Lorenzo Bernini’s intimation in this collection that her reticence regarding Judith Butler’s notion of gender performativity is itself something of a performance.6

In the months after the conference I read all of Cavarero’s work, and her thought profoundly shifted the direction of my thesis. As well as being inspired by her thematic foci, I found validation in her inter- and transdisciplinarity: it was clear that for Cavarero, responding to the major questions of twentieth-century continental philosophy required answers that did not discriminate when it came to the form or content from which they took their resources. As well as some of the major theoretical debates of the twentieth century, Cavarero also engages classical Greek texts, contemporary literature, European visual arts, and contemporary feminist politics. Each of these bodies of thought helps her articulate a philosophy that is anti-metaphysical, mounting a relentless critique of the presumptively masculine subject of the Western tradition; she demonstrates the absurdity of this figure, juxtaposing him to the singular lives of those who live in the plurality of the world. However, Cavarero is not content with critique alone. More important for her is the articulation of other forms of life—other ways of being or modes of existence—that are systematically overlooked by the gaze of the Western philosophical tradition. For Cavarero, while it is necessary to develop a critique of this tradition, including the subject fabricated by this tradition, the politics of this intervention falls short if this subject’s deconstruction becomes the telos of this work.7 For Cavarero, then, it is necessary to name the forms of life that she sees as existing despite this presumptively masculine subject, a naming that derives from the lived experience of those whose existence does not conform to his morphology or onto-epistemology. This means her interventions are necessarily identitarian but are also left productively open, encouraging others to pick up her concepts and make use of them, causing trouble in the archives of the canon of Western thought and articulating a different tradition, hidden in plain sight.

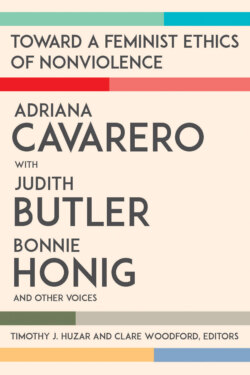

Over the next year I had the opportunity to present work to Cavarero and her colleagues in Verona, and her colleagues and students presented work at Brighton where I was studying. At various conferences I attended, Cavarero’s name was frequently mentioned by people presenting work from a variety of disciplines. It seemed strange that, given her extensive and diverse influence, an event dedicated to her thought hadn’t happened, at least in the English-speaking world. A group of us, including her colleagues Olivia Guaraldo and Lorenzo Bernini and Mark Devenney and Clare Woodford at Brighton, proposed organizing an international conference on Cavarero’s work, to be titled, “Giving Life to Politics.” The event would coincide with the English-language publication of Cavarero’s Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude, as well as marking Adriana’s seventieth birthday.8 Judith Butler and Bonnie Honig—both long-term interlocutors of Adriana’s—were invited as keynotes, and both readily accepted. The event brought together academics from across the world; there were so many compelling responses to the call for papers that the event was extended to three days. Some of those who attended had been reading Adriana since the start of her academic life; others, like me, had only recently discovered her thought. Some were long-term friends with countless stories of their time with Adriana, some not dissimilar to the story of her orchestration of the singing in Sicily where I first met her; other people were meeting Adriana for the first time. Despite a sweltering early-summer heat wave, the event was relaxed and friendly, absent of the jostling of egos that typically mark academic conferences. Like all conferences, people debated the finer points of Cavarero’s work, and while these conversations were important, what was also significant was the presence of generative conversations that occurred in between sessions, or just before a session started, or in a pub at the end of the day, or over food during dinner. Here new friendships were formed, inchoate but nonetheless important points could be expressed, support could be offered, and celebration could flourish. These ways of being can be found in any academic conference, but it is no coincidence that a conference on Cavarero’s work fostered this furtive, generative, and celebratory “co-appearing,” as she might say.9 Her work authorizes us to build new worlds; to take risks in the hope that a new sense of what it is to be—which has been right under our noses the whole time—might be made apparent. Cavarero gives us a taste of freedom that stems from her work’s generosity, free from a proprietorial control over its arguments, playful yet studiously diligent in its engagement with the thought of others. Adriana’s work is seemingly effortless in generating something akin to Hannah Arendt’s “public happiness,” and this quality is carried over into the life she leads, demonstrated by the remarkable community of people who gathered to engage with her work, to renew old friendships, and to forge new ones.10

I most recently saw Adriana in Verona, where I presented a paper and spoke to her about how this edited collection was progressing. As ever, she was supportive and encouraging, expressing her happiness and gratefulness at how the project was developing, humbly asking for feedback on her contributions and taking seriously the few substantive comments I had. As we walked back into town from the university, she bought me a gelato, and I asked about her politicization as a young person. Her earliest memories of being politically engaged involved the internal migration of southern Italians to the Northern industrial city of Turin during her teenage years in the 1960s and her activism resisting the racism that confronted them. Since then she has been involved in a number of political projects, most notably in Italian feminist movements and research groups in Padua and Rome and Diotima at the University of Verona; these were a major contributor to the development of Italian sexual difference theory, with its emphasis on an embodied, materialist approach to understanding sex / gender.11 As Olivia Guaraldo notes in this volume, these political experiences have profoundly influenced Cavarero’s work: they contributed to shaping an original combination of materiality and conceptuality; a theoretical concreteness always engaged in naming philosophically embodied singularities and their irrepressible vitality.12 It is not by chance that Cavarero’s current thought brings together two new conceptual devices to intervene in contemporary politics: first, the concept of pluriphony, which is neither the unpleasant noise of cacophony nor the pleasant noise of harmony, and is a way of articulating the vocalic sonority of a plurality of people; and second, the concept of surging democracy, which describes the pluralizing interaction present at the inaugural moments of political movements. In this way, Cavarero continues to furnish an “imaginary of hope,” which is a form of care for the world and for the singular, plural lives who both inhabit this world and constitute it, refusing their superfluity and manifesting an alternative in their everyday, spectacular sociality.13