Читать книгу The Mighty Orinoco - Jules Verne - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER III

On Board the Simón Bolívar

“The Orinoco,” Christopher Columbus wrote in his reports, “flows through a paradise on earth.”

The first time Jean quoted this pronouncement by the great Genoese navigator, Sergeant Martial had only one comment: “That remains to be seen.”

And in casting doubts on this claim by the famous discoverer of America, he just may have been right.

He likewise dismissed as so many legends the belief that the great river led to the golden land of El Dorado, as its earliest explorers seemed to think, men like Hojeda, Pinzón, Cabral, Magalhaez, Valdivia, Sarmiento, and so many others who ventured into these South American regions.1

In any case, the Orinoco traces a huge half-circle on the face of the land between the third and eighth parallels north of the equator, and this curve stretches farther than longitude 70˚ west of the meridian of Paris. All Venezuelans are proud of their river, MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas no less than their fellow countrymen.

And these three could very well have lodged a public protest against Professor Elisée Reclus who, in volume 18 of his New Geography of the World, stuck the Orinoco in ninth place among the world’s rivers, below the Amazon, Congo, Parana, Niger, Yangtze, Brahmaputra, Mississippi, and Saint Lawrence. Could not our scholarly trio have pointed out the report by the sixteenth-century explorer Diego de Ordaz2 where the Indians had nicknamed the Orinoco “Paragua,” meaning “big waters”? However, despite this potent argument, they were not inclined to voice their objections, and maybe it was just as well, because the French geographer could no doubt defend his conclusions with serious proofs.

At six o’clock in the morning on August 12, the Simón Bolívar—a name that should amaze nobody—was all set to go. Steamboat travel between this city and the villages along the Orinoco dated back only a few years and still did not go past the mouth of the Apure. Instead, the boat headed down this tributary, taking passengers and cargo to San Fernando,* and even beyond to the port of Nutrias, thanks to the Venezuela Company, which then offered bimonthly service to those destinations.

It was at the mouth of the Apure—or, rather, a couple of miles below at the village of Caicara—that travelers continuing on the Orinoco had to get off the Simón Bolívar and entrust themselves to the primitive vessels of the Indians.

As for the steamer, she was built to sail on rivers whose low-water mark changed dramatically from the dry season to the rainy season. Designed like steamboats on Colombia’s Magdalena river, she had a flat bottom and drew as little water as possible. Her only means of propulsion was a huge, uncovered paddle wheel astern, which was set in motion by a relatively powerful double-action engine. Picture a kind of raft beneath a superstructure that is crowned with two smokestacks. This superstructure, topped by a promenade deck, held the passenger lounges and cabins while the lower deck was for cargo, the whole thing recalling American steamboats with their balancing poles and superelongated connecting rods. All of it was painted in gaudy colors right up to the posts of the helmsman and the captain, a pilothouse sitting on the top story beneath the flutterings of the Venezuelan flag. As for the steam engine, it was fed by the forests ashore, and already you could see, far down both banks of the Orinoco, endless piles of timber felled by the axes of loggers.

Although Ciudad Bolívar was located over 420 kilometers from the Orinoco’s outlet, the ocean tide could still be felt there, but at least it did not disrupt the normal flow of the current. Consequently, this tide was no help to boats sailing upstream. All the same, at this location the water level can rise more than forty or fifty feet, overflowing into the city itself. But as a general rule the Orinoco rises steadily until mid-August and stays at the same level until the end of September. Then its waters abate till November, swell just a little at that point, then take until April to finish receding.

So M. Miguel and his colleagues—these feuding Orinocophiles, Guaviarians, and Atabapoists—were starting out at the most propitious time for this expedition.

Down at the loading dock of Ciudad Bolívar, a huge congregation of their followers were on hand to see the geographers off. This was merely for their departure, so just imagine the return! Supporters of the Orinoco shouted raucous encouragement, as did backers of the two upstart tributaries. Amid the carambas, carays,3 and assorted other cusswords from porters and sailors making ready for departure, and over the ear-splitting whistle of boilers and the whinnying of steam escaping through valves, you could still catch these shouts:

“Hurray for the Guaviare!”

“Three cheers for the Atabapo!”

“Let’s hear it for the Orinoco!”

Then arguments broke out between the proponents of these various viewpoints, and things threatened to get seriously out of hand, although M. Miguel tried to intervene between the fiercest contenders.

Up on the promenade deck, Sergeant Martial and his nephew were watching these rambunctious goings-on, not understanding a thing.

“What are all those people up to?” the old soldier exclaimed. “They must be trying to overthrow the government!”

That could not have been happening here, since in Spanish-American countries governments were never removed without assistance from the military. And out of those seven thousand Venezuelan generals on the standard headquarters staff, there was not a single one in sight.4

Jean and Sergeant Martial were not likely to put this squabble behind them, because one thing was certain—this debate would keep M. Miguel and his two colleagues at each others’ throats for the entire cruise.

In a flash, the captain’s final orders were passed along—first an order to the engineer to get steam up, then an order to sailors fore and aft to loosen the moorings. All those people scattered on the different decks of the ship who were not going along on the trip had to head back to the pier. Finally, after a bit of pushing and shoving, only the passengers and crew were left on board.

As soon as the Simón Bolívar got under way, the cheers increased, the good-byes became an uproar, and the Orinoco and its two tributaries were honored by outbursts of cheering. The steamboat headed out into the current, her mighty paddle wheel fiercely churning the waves and the pilot steering her toward the center of the river. Fifteen minutes later the town on the left bank had disappeared beyond a bend, and on the opposite bank those houses on the outskirts of Soledad soon passed from view.

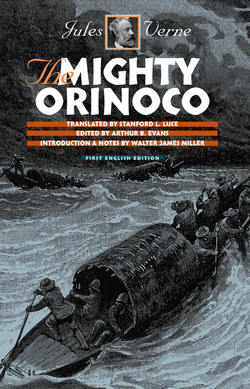

The departure of the Simón Bolívar

The grassy plains of Venezuela cover an area of some five hundred thousand square kilometers. They are open prairies, almost perfectly flat. In a few scarce locations, the landscape will add a little variety and sprout an outcrop or two, which the locals call bancos, or will swell into one of those steep-sided, flat-topped hills known as mesas. The plains rise significantly only as they approach the mountains, which were already drawing nearer. The only other bulges in the terrain are sandbars alongside the river. It is through these wide open spaces, lush and green during the rainy season, yellow and faded during the dry season, that the Orinoco flows along its semicircular course.

Moreover, if any passenger on the Simón Bolívar wanted to learn about the Orinoco from a twofold geographic and hydrographic perspective, they only had to consult MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas to understand it all. These learned men were always ready to furnish the minutest details about the villages and towns, the tributaries, and the various tribes that roamed or stayed put in the vicinity of the Orinoco. You could not have asked for trustier guides, and how amiably and eagerly they placed their wisdom at the travelers’ disposal!

Alas, among the Simón Bolívar’s passengers, the great majority had no curiosity whatever on the subject of the Orinoco, having gone up and down it twenty times already, some to the mouth of the Apure, others to the town of San Fernando de Atabapo. Most of them were merchants and traders carrying their wares inland, or exporting them to the ports back east. The usual merchandise included cocoa, cowhide, buckskin, copper ore, phosphate rock, timber, cabinetwork, marquetry, dye, tonka beans, rubber, sarsaparilla, and above all livestock, because cattle breeding is the main industry of the ranchers scattered over the Venezuelan plains.

Venezuela is in the equatorial zone. Its normal temperature range is twenty-five to thirty degrees centigrade. But in mountainous terrain it is different: it gets intensely hot between the coastal and western Andes, specifically over the lands where the Orinoco riverbed begins its curve, regions out of range of any ocean breezes. Even the major air currents—trade winds from the north and east—pull up short at the mountain barrier on the coast and do little to ease the inland heat.

That day, under an overcast sky that threatened rain, travelers did not suffer too much from the high temperatures. The steamboat met a head wind out of the west, and her passengers lounged in relative comfort.

Up on the promenade deck, Sergeant Martial and Jean observed the shores of the river, a sight in which their fellow travelers showed positively no interest. Only our trio of geographers scrutinized the passing scenery, arguing over details with their usual animation.

There is no doubt that, if Jean had consulted the geographers, he would have received up-to-the-minute information. But green-eyed, stiff-necked Sergeant Martial would not have allowed strangers to enter into such a conversation with his nephew, and anyway the lad did not need help in identifying the various villages, islands, and windings of the river. For a guidebook, Jean had a copy of M. Chaffanjon’s chronicle of his two journeys, written at the behest of France’s minister of public instruction. M. Chaffanjon’s first expedition, in 1884, covered that portion of the lower Orinoco between Ciudad Bolívar and the mouth of the Caura, plus the exploration of this important tributary. His second trip, in 1886–1887, covered the river’s whole course from Ciudad Bolívar back to its source. The French explorer’s descriptions were highly precise, and Jean thought they would be of great help.5

Sergeant Martial, needless to say, had enough money converted into piasters to handle any travel expenses. Nor had he forgotten to take along a number of articles for barter—scraps of cloth, knives, mirrors, glassware, hardware items, and cheap knick-knacks—all to facilitate relations with Indians out on the plains. These items filled up two footlockers, stowed with other luggage in the depths of the uncle’s cabin, located next to his nephew’s.

So, with his nose in his guidebook, Jean diligently studied the Orinoco’s two riverbanks as the Simón Bolívar churned its way upriver. It is true that back in the days of M. Chaffanjon’s expedition, Jean’s less fortunate countryman had to go by sailboat to the mouth of the Apure, tacking and rowing over the same route that steamers run today. But from that point on, Sergeant Martial and his young friend would likewise have to resort to this more primitive form of transportation, necessitated by all those obstacles in the river that are so exasperating to travelers.

Later that morning the Simón Bolívar passed the island of Orocopiche, whose farmlands are an abundant food source for the main town in the province. Here, the Orinoco shrinks to about half a mile across before increasing upstream to over three times that width. From the upper deck, Jean could clearly see the surrounding plains, which were punctuated with a few lonely hills.

Jean consulted his guidebook by M. Chaffanjon.

At midday the boat’s passengers—around twenty in all—answered the call to lunch in the dining room, where M. Miguel and his two colleagues were the first to be seated. As for Sergeant Martial, he was right behind them with his nephew in tow, whom he treated with a sternness M. Miguel could not help noticing.

“That Frenchman’s a tough old guy,” he commented to M. Varinas as he sat down next to him.

“He’s a soldier, what do you expect?” answered the guardian of the Guaviare.

No, one could not miss it—the old NCO was dressed in a military style that was unmistakable.

Sergeant Martial started his lunch with a little libation, downing a licorice brandy. But Jean apparently did not care for hard liquor and had no need for a before-dinner drink to do justice to the meal. He was seated at the end of the room next to his uncle, and the old veteran scowled so forbiddingly that nobody tried to sit down next to them.

As for the geographers, they monopolized both the center of the table and the conversation. Knowing the goal of their trip, the other passengers had ears only for them. Yet why was Sergeant Martial so irritated about the keen interest his nephew was displaying?

The menu had much variety but little quality; however, people were not finicky on the Orinoco boats. To tell the truth, while sailing the upper reaches of the river, some people were only too glad to eat steaks such as these, which tasted like they had been lassoed on a rubber plantation, or even the waterlogged stews in their rust-colored sauce, the eggs so hard-boiled you could skewer them, the chicken bits that only a long cooking could tenderize. As for fruit, there were plenty of bananas, but whether in their raw state or covered with molasses, they had softened into a sort of marmalade. How about the bread? Oh, it was pretty good, if you liked dry cornbread. What of the wine? Low grade, high price. In Spanish the word for lunch is almuerzo, and this, then, was the kind of almuerzo they were offered. But they still gobbled it down.

That afternoon the Simón Bolívar passed by the island of Bernavelle. Clogged with such islands and islets, the Orinoco grew narrower at this point. To overcome the strong current here, the paddle wheel had to churn the water double-time. Fortunately the captain was a capable sailor, so there was no danger of running aground.

The left side of the river offered numerous coves with tree-covered banks, notably one leading to the miniature village of El Almacén, with a population of around thirty, still exactly as M. Chaffanjon had found it eight years earlier. Nearby two tiny tributaries flowed down, the Bari and the Lima. At their mouths grew a number of mauritia palms and some clumps of copaiba trees, whose oil is drawn out through cuts in the bark and very profitably marketed. All around there were hordes of monkeys, whose meat is edible and much better than the shoe-leather steaks offered at lunch and dinner aboard the steamboat.

Islands were not the only reason the Orinoco was sometimes hard to navigate. Dangerous boulders were also encountered, which reared up suddenly in midchannel. But the Simón Bolívar successfully avoided any collisions, and by evening after a run of fifty or sixty miles she headed into the harbor at the village of Moitaco.

There she had to lay over in port till the next day, because it would not have been wise to continue on after dark with an overcast sky and no moon.

At nine o’clock in the evening Sergeant Martial thought it was time for bed, and Jean had no inclination to disobey his uncle’s orders.

So they both headed for their cabins, astern on the second story of the superstructure. Each cabin contained a plain wooden frame with a light blanket and one of those straw mats called esteras in this country—for the tropics a perfectly acceptable bed.

In his cabin, the young man undressed and lay down, then Sergeant Martial covered his bedstead with an awning—a sort of cheesecloth that is used for mosquito netting, an indispensable protection from the pesky insects of the Orinoco. He did not want a single one of those vile gnats attacking his nephew’s skin. As for his own, not to worry. The sergeant swore that his thick, leathery hide had nothing to fear from bug bites and could easily stand up to the most ferocious of them.

Thanks to these measures, Jean slept through till morning, despite the plague of tiny pests that buzzed around his protective awning.

Next day, at the crack of dawn, the Simón Bolívar, whose fires had been kept warm, set out again after the crew had returned on board and filled the lower deck with wood that had been chopped down earlier in the riverside forests.

During the night, the steamboat had berthed in one of Moitaco’s two bays, which lay to the left and right of the village. As soon as she set out from the bay, this clutch of dainty cottages, once a headquarters for the Spanish missions, vanished behind a bend in the river. It was the same village where M. Chaffanjon had searched in vain for the grave of François Burban, a comrade of Dr. Crevaux, in a grave still hidden somewhere in Moitaco’s modest cemetery.6

That day they passed by the hamlet of Santa Cruz, a collection of some twenty huts on the left bank. Then appeared the island of Guanarès, formerly a home for missionaries and almost at the spot where the river curves south only to head west again, and the island of Muerto.

There they had to go through several rapids, or in local parlance raudals, which were caused by the riverbed becoming narrower. Though these rapids usually take an exhausting toll on the crews of rowboats or sailboats, they cost the Simón Bolívar nothing more than a little extra fuel for the generators. Her valves whistled away with no stoking needed. Her huge paddle wheel dug its wide blades more fiercely into the waves. And this way she plowed through three or four rapids in practically no time, including those by the mouth of the Inferno River, which Jean identified above the island of Matapolo.

“So,” Sergeant Martial asked him, “does your old book by that Frenchman match up with everything we’re seeing from the Simón Bolívar?”

“It matches perfectly, uncle.7 Only we’ve traveled as many kilometers in one day as M. Chaffanjon did in three or four! It’s true, though, that in the central portion of the Orinoco, when we swap this steamboat for a canoe, we’ll slow down to his speed. But so what? The idea isn’t just to reach San Fernando, where I hope we’ll get more information—”

“We’re sure to! The old Colonel couldn’t possibly have gone through there without leaving some traces. We’re certain to find out where he set up camp! And when we finally lay eyes on him, when you run up and give him a hug, when he realizes—”

“That I’m your nephew … your nephew!” snapped the young man, wincing at the careless remarks blurted out by his “uncle.”

That evening the Simón Bolívar docked at the base of a gorge on the left bank. The small market town of Mapire perched gracefully above them.

They had an hour’s worth of twilight, and MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas wanted to spend it visiting this important trading center. Jean had his heart set on going ashore with them, but when Sergeant Martial said “No!” the lad obediently stayed on board.

As for our three colleagues from the Geographic Society, they had no reason to regret their outing. From its lofty perch Mapire commands a grand view of the river both upstream and down, even the grasslands to the north where Indians breed horses, donkeys, and mules on wide plains encircled by a girdle of green forests.

By nine o’clock that evening the passengers were all asleep in their cabins, after taking the usual safeguards against the armies of mosquitoes.

Their next travel day was a washout—literally—due to the many sudden cloudbursts. People avoided the promenade deck, so Sergeant Martial and his young charge spent most of the time in the lounge astern, where MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas had settled in. There, you could not help becoming well informed on the Atabapo-Guaviare-Orinoco controversy, because their respective spokesmen never discussed anything else, and loudly so. Several passengers also waded into the debate, taking various sides. But not one of them, you can be sure, would have gone to the trouble of visiting San Fernando to solve this geographic problem.

“And once it’s all settled, what’ve they accomplished?” Sergeant Martial asked his nephew. “No matter what you name it, it’s still just a river, plain ordinary water that flows where it pleases!”

“You think so, uncle?” Jean answered. “If there weren’t questions like these, there wouldn’t be any geographers, and if there weren’t any geographers—”

“—we’d have one less subject to learn in school!” Sergeant Martial cut in. “Anyhow, it’s clear that we’ll be stuck with these squabblers the whole way to San Fernando.”

In fact, after leaving Caicara, the cruise would no doubt turn into a real communal experience, aboard those small boats built to ride out the rapids in the central portion of the Orinoco.

Thanks to the bad weather on that dreadful day, they didn’t see a thing of the island of Tigritta. As compensation, guests at both lunch and dinner could treat themselves to the catch of the day, an excellent fish called morocoto. They are abundant in those parts, and enormous quantities of them are shipped, salt-preserved, to Ciudad Bolívar and Caracas.

Late in the morning the steamboat passed west of the mouth of the Caura. This waterway is one of the largest tributaries on the right bank, coming up from the southeast through the lands of the Panares, Inaos, Arebatos, and Taparitos Indians, irrigating one of Venezuela’s most picturesque valleys. The towns nearer the banks of the Orinoco are populated by law-abiding people of mixed races, Indian and Spanish. Those farther away are inhabited only by Indians, still quite uncivilized, cattlemen by trade, known locally as gomeros because their other occupation is the gathering of medicinal drugs.

Jean spent part of that day reading M. Chaffanjon’s narrative of his first expedition in 1885, during which he left the Orinoco and ventured into the grasslands along the Caura, with tribes of Ariguas and Quiriquiripas all around him. The dangers he encountered Jean was sure to face as well—and even worse if it became necessary to visit the upper reaches of the river. But Jean admired the grit and courage of the daring Frenchman, and he hoped to be just as tough and brave himself.

It is true that the former was a grown man and the latter only a youth, practically still a child. But God grant him the strength to endure such a strenuous journey, and Jean would go the distance!

Upstream from the Caura’s mouth, the Orinoco widens again—to nearly three thousand meters across. The three-month rainy season and the many tributaries on both banks make generous contributions to its water level.

Nevertheless, the Simón Bolívar’s captain had to maneuver carefully to keep from running aground above the island of Tucuragua, near a river with the same name. It was possible, too, that the steamboat might scrape against something, a thought that gave the crew no peace. The fact is, though her hull was safe, having a flat bottom like a barge, the drive mechanism was in constant danger, whether from damage to the engine or from blades breaking on the paddle wheel itself.

But this time they got through unharmed, and that evening the Simón Bolívar dropped anchor at the far end of a cove on the right bank, a town called Las Bonitas.

* This refers to San Fernando de Apure, not to be confused with San Fernando de Atabapo, which is located on the Orinoco [author’s note].