Читать книгу The Mighty Orinoco - Jules Verne - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER IV

First Encounter

Las Bonitas is the base of operation for the military governor over the Caura region and the lands irrigated by this important tributary. The village is on the river’s right bank, almost at the site formerly held by the Spanish mission of Altagracia. The missionaries were the original discoverers of these Latin American provinces, and they were intolerant of competing efforts by the British, Germans, and French to convert the wild Indians of the interior. Consequently, rivalries between these factions are still a source of concern.

At that time the military governor was present in Las Bonitas. He was personally acquainted with M. Miguel and had heard about the geographer’s expedition up the Orinoco. So, when the steamer docked, he went on board.

M. Miguel introduced his two friends to the governor. There was a hearty exchange of civilities between the various parties, including an invitation to lunch the next day in the governor’s quarters. This was promptly accepted, since the Simón Bolívar’s layover would extend to one o’clock in the afternoon.

This meant, in short, that if the steamboat left at that hour, she would have enough time to reach Caicara the same evening, where she would say good-bye to those passengers who were not continuing to San Fernando or other towns in the province of Apure.

So the next day, August 15, our three colleagues from the Geographic Society set out for the governor’s home. But ahead of them Jean and Sergeant Martial were already strolling down the streets of Las Bonitas, the sergeant having given in to his nephew and decreed that the two of them could go ashore.

In this part of Venezuela, most communities barely deserve the name of village—they are just a few scattered huts hiding beneath the lush tropical greenery. Gorgeous trees were bunched together here and there, attesting to the nutritive power of the soil: evergreen oaks with coarse, pungent leaves and crooked trunks like an olive tree’s, copernica palms with branches growing in clusters and spreading out from their stems like fans, mauritia palms that produce the kind of terrain known locally as morichal, or marshland, because this tree can suck so much water from the earth that the soil at its foot turns into mud.

Plus there were copaiba trees, saurans, and giant mimosas with wide boughs full of fine-textured, pinkish leaves.

Jean and Sergeant Martial plunged into the midst of these palm groves, which nature had organized into groups of five each, then through some riotous undergrowth where stylish bouquets of fetchingly colored poppies grew by the thousands.

Up in the trees, hordes of monkeys were romping about like trapeze artists. They are plentiful in these Venezuelan regions, numbering no less than sixteen harmless but noisy species, among others those known locally as aluates or araguatos—howler monkeys—whose voices terrify newcomers to these tropical forests. Hosts of birds were hopping from branch to branch: orioles, who made up the tenor section of this airborne chorus—roosters of the swamps, delightfully suave, seductive creatures whose nests hang from the ends of long vines; then there were a number of oilbirds hiding out in nooks and crannies, waiting for nightfall—they are fruit eaters, and they dart through the treetops as if propelled by a spring.

When they were deep into this palm grove, Sergeant Martial said, “I should’ve brought my gun!”

“Why?” Jean asked. “You want to hunt monkeys?”

“No, not monkeys. But, there might be nastier critters around!”

“Don’t worry, uncle! We’d have to go a good way out of town to run into anything dangerous—but maybe later on we’ll need a weapon.”

“Makes no difference! A soldier should never go out unarmed, and I deserve a night in the guardhouse!”

Sergeant Martial did not have to do penance for this breach of discipline. The fact is that members of the feline family, big or small, whether jaguars, tigers, lions, ocelots, or pussycats, all elected to stay far away in the dense jungles upriver. Was there any risk of running into bears?1 A little, but those flat-footed beasts live on fish or honey and have an easygoing disposition. As for the two-toed sloths (Bradypus didactylus), they are sorry creatures, not a threat to anybody.

During their stroll Sergeant Martial spotted only a few bashful rodents, among others some capybaras, plus a couple pairs of spiny rats who are speedier in water than on land.

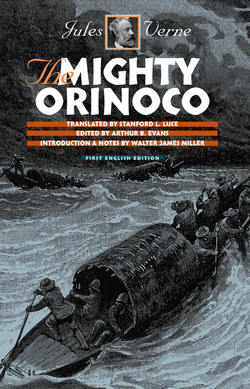

Exploring the palm grove

As for the human beings in these parts, they were mostly of mixed Spanish and Indian families. They tended to hide inside their straw huts rather than walk around outdoors, the women and children especially.

Only much farther upriver would Jean and his uncle come face to face with the Orinoco’s fiercest inhabitants, and there Sergeant Martial would do well to remember his rifle.

After a three-hour tour of Las Bonitas that left them both rather tired, they were back on board the Simón Bolívar in time for lunch.

Meanwhile MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas were gathered around the dining table in the governor’s quarters.

If the food was nothing fancy—he was the governor of a province, not the president of the republic—the guests were warmly welcomed. Naturally the three geographers talked about their mission, and the governor, being a man of prudence, was careful not to side with the Orinoco, Guaviare, or Atabapo. His main concern was to keep the conversation from degenerating into a dogfight, and more than once he changed the subject just in the nick of time.

For instance, at one particular juncture, when the voices of MM. Miguel and Varinas were taking on a certain shrillness, he created a diversion by saying: “Do you know, messieurs, if any passengers on the Simón Bolívar are traveling to the upper Orinoco?”

“No idea,” M. Miguel replied. “However, it definitely seems that most of them plan either to stop over at Caicara or sail down the Apure as far as the towns in Colombia.”

“Unless those two Frenchmen are heading upriver,” M. Varinas put in.

“Two Frenchmen?” the governor inquired.

“Yes,” M. Felipe answered, “an old-timer and a youngster who boarded at Ciudad Bolívar.”

“What’s their destination?”

“Nobody knows,” M. Miguel replied, “because they haven’t exactly been talkative. If you strike up a conversation with the boy, the old one—who seems to be a retired army officer—charges in and cuts you off. And if you keep at it, he points his finger domineeringly at his nephew—that seems to be their relationship—and orders the youngster off to his cabin. Apparently the old fellow is both his uncle and his guardian.”

“And I pity the poor lad he’s guarding,” M. Varinas added. “All that bullying really hurts the boy, and a couple of times I thought I saw tears in his eyes.”

In fact, M. Varinas was correct. But if Jean sometimes became a little teary-eyed, it was because he was thinking of the future, the goal he was seeking, and the possible disappointments lying in wait, not because Sergeant Martial treated him too sternly. It was a situation strangers could easily misunderstand.

“Anyhow,” M. Miguel went on, “tonight we’ll pretty well know if those two Frenchmen intend to continue on upriver. It wouldn’t surprise me, because the lad keeps consulting a book by a countryman of his, an explorer who managed a few years ago to reach the headwaters of the Orinoco.”

“Only if it’s on that side, in the Parima Mountains!” exclaimed M. Felipe, showing his true colors as advocate of the Atabapo.

“And only if it isn’t in the Andes Mountains!” shouted M. Varinas. “The same place of origin as the tributary we wrongly call the Guaviare!”

The governor saw that the feud was ready to roll again.

“Gentlemen,” he told his guests, “this uncle and nephew of yours interest me. If they’re not going to stop over at Caicara, and if their destination isn’t San Fernando de Apure or de Nutrias, that means they’re planning to travel to the upper reaches of the Orinoco—and I have to wonder why. Frenchmen don’t mind taking chances, they’re daring explorers. I know that. But a number of them have already lost their lives in these South American territories—Dr. Crevaux was clubbed to death by Indians in the plains of Bolivia; his companion François Burban died in Moitaco, and his grave has never been found in the town cemetery. It’s true, though, that M. Chaffanjon was able to make it to the source of the Orinoco—”

“If it really is the Orinoco!” broke in M. Varinas, who could not let this go by without strenuous objection.

“Yes, if it really is the Orinoco,” the governor replied. “And that geographic question, gentlemen, will be settled conclusively by your trip. All I mean is that M. Chaffanjon managed to get back safe and sound, even though he faced the same dangers as his predecessors. So, even without counting your two passengers on the Simón Bolívar, it seems this mighty river of ours draws Frenchmen like flies.”

“As a matter of fact, you’re right,” M. Miguel commented. “Some weeks back, a couple more of those daredevils took off on an exploratory survey of the plains east of the river.”

“Absolutely true, M. Miguel,” the governor said. “They even called on me here—two youngish men about twenty-five or thirty, one an explorer named Jacques Helloch, the other a naturalist named Germain Paterne, one of those naturalists who would risk his neck just to discover a new sprig of grass.”

“And you haven’t had any news since?” M. Felipe asked.

“Nothing, gentlemen. I only know they left by canoe for Caicara, reported in at Buena Vista and La Urbana, then went up one of the tributaries on the right bank. But since that last stopover, nobody has heard a thing from them, and we have good reason to be worried!”

“Let’s hope,” M. Miguel said, “those two explorers haven’t fallen into the clutches of the Quivas Indians—who’re nothing but thieves and murderers, and small wonder they were chased out of Colombia into Venezuela! Their leader is said to be an escaped convict, a man named Alfaniz2 who broke out of the prison at Cayenne.”3

“Is that a certainty?” M. Felipe asked.

“Seems to be,” the governor added, “and I fervently pray, gentlemen, that you yourselves never meet up with any band of Quivas. But still, it’s just possible those audacious Frenchmen haven’t been ambushed and are simply continuing on their merry way, so any day now they may show up again at some village on the right bank. It could be they’ll pull it off just like M. Chaffanjon! But aside from them, there’s also talk of a missionary who went even deeper into these territories to the east, a Spaniard named Father Esperante. After a short stay at San Fernando, this missionary dared to travel even farther than the headwaters of the Orinoco!”

“The false Orinoco!” MM. Felipe and Varinas exclaimed in unison.

And they glared at their colleague, who bowed graciously. “Have it your way, my friends,” M. Miguel said. Then he added to the governor, “Do you know if this missionary ever managed to set up a mission?”

“He has—the Mission of Santa Juana, near Mount Roraima. Apparently it’s doing rather well.”

“That’s quite an achievement!” M. Miguel conceded.

“Indeed,” the governor answered, “and even more because it involves the Guaharibos, the most backward of all the Indian settlers out in the southeast territories. He’s apparently civilized them, converted them to Catholicism, and generally rehabilitated them. And those poor creatures were the lowest of the low, so you can’t even imagine the courage, patience, selflessness—in short, the apostolic virtue—it must’ve taken to accomplish this humanitarian task. During Father Esperante’s early years there, we had no news of him, and in 1888 M. Chaffanjon hadn’t heard a thing about the Santa Juana Mission, even though it wasn’t far from the source of the … uh … river.”

The governor hastily avoided saying “the Orinoco,” not wanting to start another conflagration.

“But,” he continued, “two years ago word came to San Fernando of his success—thanks to him those Guaharibos are now enjoying the miraculous advantages of civilization!”

For the rest of their breakfast, the conversation dealt with the territories along the central portion of the Orinoco (thankfully noncontroversial) and the current condition of the Indians there—both those who had been tamed and those who resisted any kind of domination, who fiercely resisted, to be blunt, the forces of civilization itself. The Caura governor furnished many specifics about the natives, valuable details that M. Miguel, as knowledgeable as he was in geographic matters, had not heard until that day. Moreover, their discussion never deteriorated into a heated dispute, since it did not ruffle the feisty feathers of MM. Felipe and Varinas.

Close to noontime the governor’s guests got up from the table and headed back to the Simón Bolívar, due to depart at one o’clock in the afternoon.

Uncle and nephew, having already returned for lunch, had remained on board. Astern on the upper deck, where Sergeant Martial was smoking his pipe, they spotted M. Miguel and his colleagues off in the distance, coming back to the boat.

The governor had decided to accompany them. Wishing to give them a last handshake and bid them farewell as the boat was casting off, he came aboard and went up to the promenade deck.

At this, Sergeant Martial said to Jean: “That governor’s got to be at least a general—though he has on a jacket instead of a tunic, a sombrero instead of a cocked hat, and no medals on his chest.”

“Could be, uncle.”

“One of those generals without soldiers—there are quite a few in these American republics.”

“He seems like a pretty intelligent man,” the lad commented.

“More like a pretty nosy man,” Sergeant Martial shot back. “Because he’s looking over here in a way I can hardly tolerate.”

It was true, the governor kept staring intently at the two Frenchmen who had been a topic of conversation at his lunch table.

Their presence on the Simón Bolívar, their reason for taking this trip, the question of whether their destination was Caicara or somewhere farther along the Apure or the Orinoco—all this continued to arouse his interest. Generally, explorers of these rivers were men in the prime of life, like the two who had visited Las Bonitas a few weeks before and had not been heard from since they left La Urbana. But this young man of sixteen or seventeen, plus this old soldier of sixty—it was hard to picture them on any kind of scientific expedition!

After all, even in Venezuela a governor has the right to look into why foreigners are visiting his territory, to speak with them about it, to ask them a few bureaucratic questions.

So the governor strolled toward the stern of the promenade deck, all the while chatting with M. Miguel, who had the official to himself after his two colleagues had gone back to their cabin.

Sergeant Martial could instantly see what was up.

“Watch out!” he said. “Our general’s all set to approach us, and I guarantee he’ll ask us who we are, why we’re here, where we’re headed—”

“Fine, my dear Martial, we haven’t a thing to hide,” Jean replied.

“I hate it when people poke into my affairs, and I’m going to tell him to just leave us be.”

“You’ll get us in trouble, uncle!” the lad said, holding him back.

“I don’t want anybody talking to you. I don’t want anybody around you.”

“And I don’t want you ruining our trip with your clumsy stubbornness!” Jean retorted, putting his foot down. “This man’s governor of the Caura region. If he asks me a question, I’ll gladly answer, and hopefully I’ll get some information from him in return.”

Sergeant Martial grumbled to himself, and puffed resentfully on his pipe. He pulled in closer when the governor addressed his nephew in Spanish, which Jean spoke fluently.

“You’re French?”

“That’s right, Mr. Governor,” Jean replied, facing the official.

“How about your friend here?”

“My uncle. He’s a Frenchman also, a retired army sergeant.”

Despite his shaky grasp of Spanish, Sergeant Martial understood they were talking about him. Accordingly, he drew himself up to his full height, believing that a French sergeant of the 72nd Division equaled a Venezuelan general any day, including those who governed entire territories.

“I don’t think I’m out of line, young fellow,” the governor went on, “if I ask whether you’ll be traveling farther than Caicara.”

“Yes, we’ll be going farther, Mr. Governor,” Jean answered.

“Up the Orinoco or the Apure?”

“The Orinoco.”

“As far as San Fernando de Atabapo?”

“That far, Mr. Governor. Maybe even farther, if I get any information there that calls for it.”

The governor, along with M. Miguel, was deeply impressed with Jean’s crisp manner and clear answers, and it was obvious they both had a genuine liking for the young man.

Now then, Sergeant Martial aimed to protect the lad from just this kind of overt attention. He did not like anybody inspecting Jean too closely; he did not want other people—foreigners or not—appreciating his nephew’s natural grace and charm. And what upset the sergeant even more was M. Miguel’s obvious interest in the lad. The Caura governor was not important since he would stay behind in Las Bonitas. But M. Miguel not only was a passenger on the Simón Bolívar, he was also continuing up the river to San Fernando. Once he got acquainted with Jean, it would be hard to keep them from becoming friendly, which often happens among travelers on a long trip.

And why not? one might ask Sergeant Martial.

If, during their risky Orinoco journey, uncle and nephew were helped by some influential person, what would be wrong if he became close to them in the process? That would be perfectly normal, would it not?

Of course. And yet if you were to ask Sergeant Martial why he would throw obstacles in the way of such a budding friendship, he would only growl, “Because I don’t like it, that’s why!” And you would have to be happy with that, because it is the only answer you would ever be likely to get from him.

However, at this point he had to put up with the governor and let his nephew converse with the man.

Just then the official was busy questioning Jean on the purpose of his trip. “You’re going to San Fernando?” he asked the boy.

“Yes, Mr. Governor.”

“That far, Mr. Governor. Maybe even farther … ”

“For what purpose?”

“To get information.”

“Information about what?”

“About Colonel de Kermor.”

“Colonel de Kermor?” the governor repeated. “This is the first time I’ve ever heard that name. And I haven’t heard about any Frenchman being in San Fernando since the days of M. Chaffanjon.”

“But he was there a few years earlier,” the young man noted.

“How do you know that?” the governor asked.

“Because of the last letter the Colonel sent to France, a signed letter to a friend of his in Nantes.”

“So, young man,” the governor went on, “you’re saying that Colonel de Kermor stayed in San Fernando some years ago?”

“No doubt about it. His letter was dated April 12, 1879.”

“That’s amazing.”

“How so, Mr. Governor?”

“Because I was there at that time as governor of Atabapo, and if a Frenchman like Colonel de Kermor had shown up in the region, I definitely would have known about it. But I don’t recall a thing.”

The governor’s explicit denial seemed to affect the young man deeply. The color drained from his face, which had been quite animated during the conversation. He turned white, his eyes glistened, and it took an enormous effort for him not to lose control.

“Thank you, Mr. Governor,” he said. “Thank you for the interest you have in my uncle and me. You’re certain that you’ve never heard of Colonel de Kermor, but we are just as sure he visited San Fernando in April 1879. That is where his last letter was mailed from, and we received it in France.”

“What was he doing in San Fernando?” M. Miguel asked, a question that the governor had not yet raised.

Sergeant Martial gave him an ugly scowl and muttered between his teeth: “Now the other one’s butting in. What’s he trying to do?”

Jean nevertheless answered without hesitation, “I don’t know. That’s a mystery we hope to solve, if the good Lord allows us to catch up with him.”

“Then what’s the connection,” the governor asked, “between you and Colonel de Kermor?”

“He’s my father,” Jean answered. “I’m here in Venezuela to find my father.”4