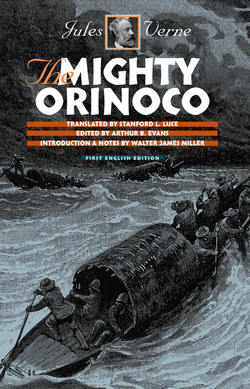

Читать книгу The Mighty Orinoco - Jules Verne - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER I

M. Miguel and His Two Colleagues

“There is not the slightest reason to believe that this discussion can come to an end,” said M. Miguel, who was seeking to intervene between the two fiery discussants.

“Well, it won’t end,” answered M. Felipe, “not if it means sacrificing my views to those of M. Varinas!”

“Nor by abandoning my ideas for those of M. Felipe!” replied M. Varinas.

For nearly three full hours, these stubborn scholars had been arguing about the Orinoco Question, neither giving an inch. Did this well-known river of South America, the primary waterway of Venezuela, flow in the first part of its course from east to west, as the most recent maps indicated, or did it flow from the southwest? In the latter case, were not the Guaviare or the Atabapo wrongfully considered to be its tributaries?1

“The Atabapo is really the Orinoco,” M. Felipe affirmed stubbornly.

“It’s the Guaviare,” affirmed M. Varinas no less energetically.

As for M. Miguel, he sided with the geographers of the day. According to them, the Orinoco’s sources are located in that section of Venezuela bordering on Brazil and British Guyana, making this river Venezuelan throughout its entire length. But M. Miguel tried in vain to convince his two friends, who were bickering over a point of no little importance.

“No,” one kept repeating, “the source of the Orinoco is in the Colombian Andes. The Guaviare, which you claim is a mere tributary, is quite simply the Orinoco itself, Colombian in its upper course, Venezuelan in its lower course.”

“Totally erroneous,” the other avowed. “It’s the Atabapo that is the true Orinoco, and not the Guaviare.”

“Come now, my friends,” answered M. Miguel. “I prefer believing that one of the most beautiful rivers in America at least belongs to our own country.”

Three geographers: MM. Miguel, Filipe, and Varinas.

“It’s not a question of self-esteem,” replied M. Varinas, “but rather of geographic fact. The Guaviare—”

“No! The Atabapo!” exclaimed M. Felipe.

And the two adversaries, who had sprung to their feet, glared into the whites of each other’s eyes.

“Gentlemen … gentlemen!” repeated M. Miguel, a fine man and very conciliatory by nature.

There was a map hanging on a wall of the room, which was shaking from the outbursts of this discussion. On that map, in great detail, was an area of nine hundred seventy-two thousand square kilometers of the Spanish-American country of Venezuela. Political events had greatly modified it since the year 1499 when Hojeda, companion of the Florentine Amerigo Vespucci,2 disembarked on the shore of the Gulf of Maracaibo3 and discovered a village built on pilings in the middle of the lagoons, to which he gave the name Venezuela, or “Little Venice.” Then came the war of independence and the heroism of Simón Bolívar,4 then the founding of the military post in Caracas, then the separation that took place in 1839 between Colombia and Venezuela, a separation that turned the latter into an independent republic—the map represented Venezuela according to its present legal status. Colored lines separated the region of Orinoco into three provinces: Varinas, Guyana, Apure. The elevations of its orographic relief and the branchings of its hydrographic system stood out clearly by the multiple hachures and the network of its rivers and streams. One could also make out its maritime border along the Caribbean Sea, extending from the province of Maracaibo, with its capital city of the same name, to the mouths of the Orinoco, which separate it from British Guyana.

M. Miguel was looking at the map, which by all evidence proved him to be more right than his colleagues, Felipe and Varinas. Indeed, on the surface of Venezuela, meticulously drawn, a great river was marked by an elegant semicircle. Both along its first curve, which was fed by the waters of a tributary, the Apure, as well as along its second, where the Guaviare and the Atabapo brought to it the waters of the Andean Cordilleras, it was uniquely baptized with the magnificent name of Orinoco along its entire course.5

Why then did Varinas and Felipe persist in seeking the origins of this watercourse in the mountains of Colombia and not in those of the Sierra Parima next to the gigantic military column of Mount Roraima, 2,300 meters high, at the intersection of these three South American states of Venezuela, Brazil, and British Guyana?

The Orinoco River.

It is only fair to mention that these two geographers were not the only ones to profess such an opinion. Despite the assertions of intrepid explorers who had gone up the Orinoco practically to its source, Diaz de la Fuente in 1760, Bobadilla in 1764, and Robert Schomburgk in 1840, and despite the exploration by the Frenchman M. Chaffanjon, the daring traveler who had raised the French flag on the slopes of the Parima as it oozed out the first drops of water of the Orinoco—yes! despite so many reports which appeared to be conclusive, the question was still not resolved for certain tenacious minds, disciples of Saint Thomas, who were as demanding about proof as was this ancient patron of incredulity.6

However, to claim that this question impassioned the public of that day, in the year of 1893, would be exposing oneself to the charge of exaggeration. If, two years before, people had taken an interest in the drawing of borders when Spain, charged with the arbitration, set the definitive limits between Colombia and Venezuela, so be it. Likewise if it had involved an exploration to determine the border with Brazil. But out of 2,250,000 inhabitants, which include 325,000 Indians, “tamed” or independent in the middle of their forests and their prairies, and 50,000 blacks, then of mixed blood, half-breeds, whites, and foreigners of English, Italian, Dutch, French or German origin there was no doubt that only a very small minority could become worked up over this hydrographic thesis. In any case, there were at least two Venezuelans who were—Varinas, who claimed for the Guaviare the right to be called the Orinoco, and Felipe, who claimed the same right for the Atabapo—without counting a few partisans who, if need be, would lend them support.

One should nevertheless not believe that M. Miguel and his two friends were just any old scholars, encrusted in science, bald-headed and with white beards. No! They were scholars who all three enjoyed a deserved reputation which went beyond the limits of their country. The oldest, M. Miguel, was forty-five, and the other two were a few years younger. Very intense and demonstrative, they were true to their Basque origins, much like the illustrious Bolívar or even the majority of whites in those republics of South America who sometimes had a bit of Corsican or Indian blood in their veins but not a single drop of Negro blood.7

These three geographers would get together every day at the library of the University of Ciudad Bolívar. There both Varinas and Felipe, as determined as they were not to start it all over, let themselves be carried away in an interminable discussion about the Orinoco. Even after the very convincing exploration of the French traveler, the defenders of the Atabapo and the Guaviare stuck to their beliefs.

This was clear in the few replies reported at the beginning of this story. And the dispute went on, continuing with greater intensity, despite M. Miguel, who was powerless to dampen the enthusiasm of his two colleagues.

He was, however, an impressive person with his tall stature, his noble, aristocratic demeanor, his brown beard with a few silver strands in it, his position of authority, and his top hat, which he wore like the founder of the Spanish-American independence did.

And that day M. Miguel repeated in a strong, calm, penetrating voice, “Don’t lose your tempers, my friends! Whether it flows from the east or the west the Orinoco is nonetheless a Venezuelan river, the father of the waters of our republic!”

“It’s not a question of knowing whose father it is,” replied the boiling Varinas, “but whose son it is, if it was born on the Sierra Parima or in the Colombian Andes.”

“In the Andes … in the Andes!” countered M. Felipe, shrugging his shoulders.

Obviously, neither man would capitulate on the subject of the birth certificate, each attributing a different father.

“Come, come, dear colleagues,” went on M. Miguel, desirous of bringing them to an agreement. “It is enough to cast your eyes on this map to recognize the following: wherever it comes from, and especially if it comes from the east, the Orinoco forms a graceful curve, a semicircle better shaped than that awkward zigzag that either the Atabapo or the Guaviare would give it—”

“So what difference does it make whether the shape is harmonious or not?” exclaimed M. Felipe.

“As long as it’s exact and conforms to the nature of the territory!” added M. Varinas.

And, indeed, it was of little importance whether the curves were or were not artistically drawn. It was a purely geographical question, not a question of art. M. Miguel’s argument missed the point, but that was the way he felt. So the thought came to him to throw into the discussion a new element that would change its focus. It would, no doubt, not be the way to bring the two adversaries together. But, perhaps, like hunting dogs turned aside from their prey, they would charge off fiercely in pursuit of another wild boar.

“Fine,” said M. Miguel, “let’s forget about that way of looking at it. You claim, Felipe, and with such obstinacy! that the Atabapo, far from being a tributary of our great river, is the river itself.”

“That’s what I claim!”

“And you hold the view, Varinas, and with equal obstinacy! that, on the contrary, the Guaviare must be the Orinoco in person.”

“That’s my view.”

“Well,” replied M. Miguel, whose finger followed on the map the watercourse under discussion, “why wouldn’t you both be making a mistake?”

“Both of us?” exclaimed M. Felipe.

“One of us is indeed wrong,” affirmed M. Varinas, “and it’s not me!”

“Then listen to what I have to say,” said M. Miguel. “And don’t give me your answer until you’ve heard me out. There exist other affluents than the Guaviare and the Atabapo that flow into the Orinoco, tributaries with important characteristics in the routes they follow and the amount of water they contribute. Such are the Caura in the northern section, the Apure and the Meta in the western section, the Cassiquiare and the Iquapo in the southern area. Do you see them there, on this map? Well, I ask you, why should not one of these feeder streams be the Orinoco rather than your Guaviare, my dear Varinas, and your Atabapo, my dear Felipe?”

It was the first time that this proposition had ever been suggested, and it is not surprising that the two opponents remained quite speechless at first upon hearing him spell it all out. What? The question was not limited simply to the Atabapo and the Guaviare? What did he mean, other candidates might emerge?

“Come now!” exclaimed M. Varinas. “That’s not reasonable. You’re not talking seriously, M. Miguel!”

“Very seriously, on the contrary! And I find the opinion quite natural, logical, and thus entirely admissible that other tributaries can contest the honor of being the true Orinoco.”

“Surely you’re joking!” retorted M. Felipe.

“I never joke when it’s a question of geography,” M. Miguel responded gravely. “On the right bank of the upper reach of the Padamo—”

“Your Padamo is but a stream compared to my Guaviare!” countered M. Varinas.

“A stream that geographers consider as important as the Orinoco itself,” answered M. Miguel. “On the left bank you’ll find the Cassiquiare—”

“Your Cassiquiare is but a brook compared to my Atabapo!” shouted M. Felipe.

“A brook that communicates between the Venezuelan and Amazonian basins! On the same shore there’s the Meta—”

“But your Meta is only the faucet of a fountain!”

“A faucet that turns out a flow of water that economists look upon as being the future route between Europe and the Colombian territories.”

It was evident that M. Miguel was well documented and had an answer for all occasions, as he continued.

“On the same bank,” he said, “there’s the Apure, the prairie river that ships can go up for more than five hundred kilometers.”

Neither M. Felipe nor M. Varinas contested this affirmation. The reason for this was that they were half suffocated by M. Miguel’s nerve.

“Well,” added M. Miguel, “on the right bank, you’ll find the Cuchivero, the Caura, the Caroni—”

“When you get done with all the nomenclature—” said M. Felipe.

“We’ll discuss the subject,” added M. Varinas, who had just folded his arms.

“I’m done,” answered M. Miguel, “and if you want to know my personal opinion—”

“Is it worthwhile?” retorted M. Varinas in a tone of supreme irony.

“Not very likely!” declared M. Felipe.

“Here’s what I think, anyway, my dear colleagues. None of these affluents could be considered the mainstream, the one that is legitimately called the Orinoco. So I believe that this name can neither be applied to the Atabapo, recommended by my friend Felipe—”

“An error!” replied the latter.

“—nor to the Guaviare, recommended by my friend Varinas!”

“Heresy!” responded friend Varinas.

“And I conclude,” added M. Miguel, “that the name of Orinoco should be saved for the upper region of the river whose sources are situated in the Sierra Parima. It flows entirely across the territory of our republic and it does not irrigate any other. The Guaviare and the Atabapo should be willing to take on the role of simple tributaries, which is, after all, a very acceptable geographic situation.”

“That I do not accept!” replied M. Felipe.

“That I refuse!” echoed M. Varinas.

The lone result of M. Miguel’s intervention in that hydrographic discussion was that now three people rather than two were at each other’s throats over which was the true source, the Guaviare, the Orinoco, or the Atabapo. The quarrel continued for another hour and would perhaps never have come to an end if M. Felipe on the one hand and M. Varinas on the other had not exclaimed, “Well, let’s go!”

“Go?” responded M. Miguel, who was scarcely expecting such a proposal.

“Yes!” added M. Felipe, “let’s head for San Fernando and there, if I can’t prove to you right off that the Atabapo is really the Orinoco—”

“And I,” retorted M. Varinas, “if I can’t prove once and for all that the Orinoco is the Guaviare—”

“That’s because,” said M. Miguel, “I will have forced you to recognize that the Orinoco is just the Orinoco!”

And this is how, as a result of this discussion, these three people resolved to undertake such a trip. Perhaps this new expedition would finally decide once and for all the real course of the Venezuelan river, provided that it had not been already so determined by the latest explorers.

Moreover, it was only a question of going up to the village of San Fernando, to the bend in the river where the mouths of the Guaviare and the Atabapo are located, only a few kilometers apart from each other. If it could be established that neither one nor the other was or could be anything more than a simple affluent, then it would be necessary to yield to M. Miguel and to confer upon the Orinoco its official status as the main river, which these unworthy streams would no longer be able to deny.

One should not be greatly surprised if this resolution, born in the course of a stormy spat, was soon to be followed by an immediate effect. Nor should one be surprised by the immediate repercussions it produced in the scientific world, among the upper classes of Ciudad Bolívar, and soon among the whole Venezuelan republic.

With some cities, it is just like with some men: before setting up a fixed and definitive residence, they hesitate, they feel their way along. That is what happened to the provincial capital of Guyana from the date of its appearance in 1576, on the right bank of the Orinoco.8 After being established at the mouth of the Caroni under the name of San Tome, it had been reported ten years later at a location fifteen leagues downstream. Destroyed by fire under the orders of the famous Sir Walter Raleigh,9 it had moved, in 1764, some hundred and fifty kilometers upstream, to a site where the width of the river was reduced to less than eight hundred yards. Hence the name of Angostura, the “narrows,” that was given to it until it eventually became Ciudad Bolívar.

This provincial capital is situated about a hundred leagues from the Orinoco delta, whose low-water mark, indicated by the Midio Rock rising up in the middle of the current, varies considerably from the dry season of January to May, the rainy season.10

This city, which was given some eleven or twelve thousand inhabitants by the latest census, includes the suburb of Soledad on the left bank. It extends from the Alameda promenade up to the “Dry-dog” quarter, which has a rather curious name since this low-lying district, more than any other, is subject to flooding caused by the sudden and copious high waters of the Orinoco.11 The main street, with its public buildings, its elegant stores, its covered galleries, the houses spread over the flank of the schistose hill which rises above the city, the spread of rural houses under the trees which cradle them, the sort of lakes that the river forms as it widens both up and downstream, the movement and animation of the port, the numerous ships of both sail and steam attesting to its bustling river commerce, which is supplemented by its substantial trade on land—all this contributed to make the area quite charming and picturesque.

Through Soledad, where the railroad is to end, Ciudad Bolívar will not be long in linking up with Caracas, the capital of Venezuela.12 Its exports in cow and deer hides, in coffee, cotton, indigo, cacao, and tobacco will thus be expanded, adding to its already sizeable increases due to the mining of deposits of gold-bearing quartz, discovered in 1840 in the valley of Yurauri.

So the news that the three scientists, members of the Geographic Society of Venezuela, were going on an expedition to settle the question of the Orinoco and its two tributaries in the southwest caused a great stir throughout the country. The Bolívarians are a demonstrative sort, passionate and fiery by nature. The newspapers soon became involved, taking sides with the Atabapoists, Guaviarians, and the Orinocophiles. Public sentiment became inflamed. One might really have thought that these waterways were threatening to rise up from their beds, to leave the country, to emigrate to some other state in the New World if they were not treated fairly.

Did this journey upriver hold any serious dangers? Yes, especially for travelers with only themselves to rely on. So would it not have been appropriate for the government to make a few sacrifices to solve this critical problem? Was not this a clear opportunity to use the militia, which could put 250,000 men in the field but which has never called up more than a tenth of them? Why not assign the explorers a unit of 6,000 soldiers from this standing army whose upper ranks include, according to Elisée Reclus who is always so perfectly documented in such ethnographic curiosities,13 up to 7,000 generals plus a lavish assortment of other officers?14

But MM. Miguel, Felipe, and Varinas asked for no such help. They would travel at their own expense, escorted only by the laborers, ranchers, boatmen, and guides who reside along the banks of the river. They would proceed in the same fashion as all other pioneers of science before them. Besides, they did not have to go beyond the village of San Fernando, which had been built at the junction of the Atabapo and Guaviare. Further, it is mainly in the lands along the upper reaches of the river that there is a danger of attack by Indians from independent tribes who are difficult to contain and who are sometimes justly blamed for the massacres and looting in those parts, which is not surprising in a region that used to be inhabited by the Caribes.

To be sure, downstream of San Fernando in the lands opposite the mouth of the Meta, it is also wise to avoid both the Guahibo Indians, so resistant to social laws, and the Quivas, whose reputation for savagery is well deserved, thanks to the outrages they perpetrated in Colombia before moving to the banks of the Orinoco.

As a result, there was definite uneasiness in Ciudad Bolívar concerning the fate of two Frenchmen who had gone off on a similar expedition about a month before. After heading up the river past its junction with the Meta, these two travelers had ventured into Quiva and Guahibo territory and had not been heard from since.

News of the expedition caused a great stir.

But all the same, the upper reaches of the Orinoco are infinitely worse: completely uncharted territory, out of reach of the Venezuelan authorities, never visited by traders, and at the mercy of prowling bands of natives. In truth, if the Indian settlers to the west and to the north of the main river are well mannered and devoted to agricultural pursuits, those who live in the low grasslands of this Orinoco district are a different story entirely. They are thieves by both greed and necessity, and they are no strangers to treachery or murder.

Would it be possible someday to tame these fierce and indomitable people? What cannot be achieved with the beasts of the plains, can it be achieved with the natives of the upper Orinoco flatlands? The truth is that even the bravest missionaries who have tried have had no great success.

One of them, a Frenchman from the foreign missions,15 went some years back to these regions upriver. Had his faith and courage paid off? Had he subdued these savage tribes and converted them into practicing Catholics? These Indians had resisted civilization’s best efforts—was there any reason to think that this courageous emissary from the Santa Juana Mission had finally managed to gather them into the fold?16

In any case, to return to M. Miguel and his two colleagues, it was not a question of venturing into those far-off lands beneath Mount Roraima, although if geographic progress had demanded it, they would not have balked at charting the respective sources of the Orinoco, the Guaviare, and the Atabapo. Still, their friends were realistically hopeful that this question of origins could be settled at the place where these three rivers meet. It was generally accepted that Orinoco’s preeminence would ultimately prevail—this mighty river which is joined by some three hundred streams over its course of 2,500 kilometers before branching into the fifty arms of its delta and flowing into the Atlantic.